England’s Vanishing Aristocrats

Nearly 70 years ago, in September 2, 1950, issue of The Saturday Evening Post, writer James P. O’Donnell wrote forlornly about the dwindling prospects of England’s noble class. Having spent a fortnight at Compton Wynyates, ancestral home of the Marquess of Northampton and one of “the finest of the great houses of England,” O’Donnell lamented that the British Labor government’s high income and estate taxes had “threatened the existence of this noble house.” He notes that “The little master, Earl (Spenny) Compton, age four, the seventh marquess-to-be, is too young and too happy to realize that he may never lord it over this manor.”

Of course, the sixth and at-the-time current marquess wasn’t exactly penniless in 1950. O’Donnell notes that, in addition to Compton Wynyates, his lordship was also in possession of “the far larger winter estate of Castle Ashby in the neighbouring county of Northampton, a summer estate at Lochluichart in the Scottish Highlands, 10,000 acres of land and forest in scattered English shires, valuable real estate in London’s swank West End, land and properties in many parts of the Empire from Rhodesia to Bermuda, a fifty-six-ton yawl at Cowes, et cetera and inter alia. Nor are his art collections to be sniffed at. A well-heeled American visitor to the Castle Ashby galleries offered him $1,000,000 for one painting — Mantegna’s Adoration of the Wise Men —and was politely refused.”

Even without resorting to selling valuable artworks or – God forbid – “having to pose as a man of distinction in highball ads,” sacrifices had to be made. As anyone who has studied the economic goings-on in Downton Abbey can attest, times did indeed become more challenging at these country estates through the 20th century. There were options, provided in part by anglophile Americans:

If there is anybody in England more given than the English themselves to gawking at the gentry, it’s their transatlantic cousins. This has begun to dawn on the British Travel Association, a hard-boiled unsentimental outfit out to corral dollars from American visitors, who feel nothing will bring tourists quicker to a country house than a flesh-and-blood nobleman in residence. To a dollar-starved British Exchequer this puts milord high on the list as a national asset, a good thing.

To help with upkeep, tourists were allowed into the manor house on weekends (40 cents a head), much to the resignation of the marquess: “I do feel a bit like a fly on a white plate. I’m what they all come to see, you know. Can’t say that I blame them really—there’s so little gracious living left anywhere today.”

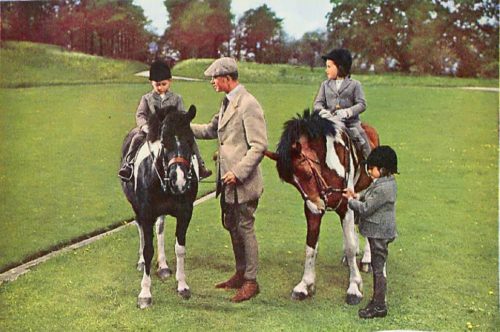

Compton Wynyates also saw its servant staff dwindle from 60 to 12: (“…a butler, a chef, two scullery maids who double at table, a caretaker and his housekeeper wife, two lady’s maids, a chauffeur, a governess and nanny for the four children, and two gardeners who triple as guides and footmen.”)

After two weeks of tea, great halls, and formal gardens, the Post writer came down firmly on the side of the nobles. He bemoaned that the Labour Party’s high taxes would drive the landowners from their estates and that “life will never be lived as it was in the good old days, and his son will be a far poorer man than he.”

But Dear Reader, please don’t fret over the fate of the article’s four-year-old Spenney Compton. While he did eventually sell Mantegna’s Adoration of the Magi to the Getty Museum in 1985 for $10.4 million (a then-world record auction price), the seventh Marquess of Northampton has a current estimated net worth of £110 million. And while the family’s other, larger property, Castle Ashby, was for a while commercialized and open to the public, at the current time both homes are private residences of the Compton family.

Featured image: Compton Wynyates (Photo by Eugene Kammerman)