From Our Archives: One-on-One with Mike Wallace

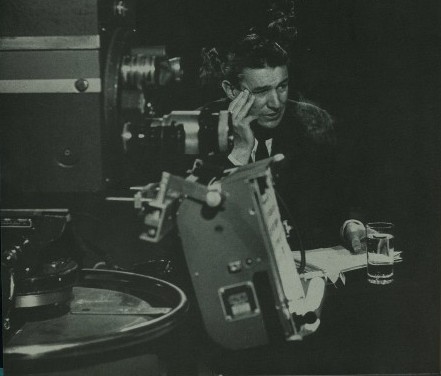

Intense, probing, relentless, fearless—Mike Wallace, 60 Minutes’ grand inquisitor, was an intimidating presence. Here was the man who interviewed presidents and world leaders—from John F. Kennedy to Yasser Arafat, Ayatollah Khomeini to Deng Xiaoping—with complete equanimity. An investigative journalist who doggedly pursued a lead—whatever the cost.

When asked to broach the veteran journalist’s long-standing battle with depression, I was initially intimidated, uncertain how best to broach a very personal conversation.

I took a tip from the best. Mirroring the intrepid journalist’s own trademark style, I jumped in.

And with good humor and characteristic candor, Wallace took a deep breath, leaned back in his chair, asked if it was okay to unpeel an orange for lunch at his desk, then slowly shared his long-standing struggle with what Winston Churchill dubbed the “black dog” of depression. For years, Wallace suffered from the disease in silence, leaning on his wife for support. Later, Wallace turned to the counsel of good friends Art Buchwald and William Styron—who also battled depression; the trio dubbed themselves “The Blues Brothers.”

Despite the on-camera bravado and self-confidence, Wallace was humbled by depression—engulfed by a darkness that at one point in his life led him to attempt suicide. Going public to help others was a brave move for the respected anchorman who to the unsuspecting audience appeared untouched by uncertainty or self-doubt. But he was. And he survived. And he wanted others to know that they could survive as well.

Thank you, Mike, for sharing “60 minutes” with the Post.

MIKE WALLACE: SPEAKING OUT ON DEPRESSION

By Patrick Perry from Sept/Oct 2006

Tough, hard-hitting, and respected, news correspondent Mike Wallace has made his living tackling complex problems. For years, the popular 60 Minutes anchor confronted corruption and fraud, interviewed the famous and infamous, and survived the loss of a son and numerous life challenges. But in his mid-60’s, he began to suffer from what Winston Churchill called the “black dog” of an overwhelming depression that spiraled out of control, carrying Wallace to the brink of suicide.

“My colleagues and I at CBS were on trial for defamation,” Wallace told the Post. ‘We aired a piece about General [William] Westmoreland, and he decided that he was going to sue CBS for Sl20 million. It went through deposition and finally, after a couple of years, wound up in court. It was—to put it mildly—harrowing.”

For five grueling months, Wallace became a central figure in the courtroom drama, with his most precious professional credential—his credibility—on trial. Little by little. Wallace began to experience psychosomatic pain. “I couldn’t sleep, couldn’t think straight, was losing weight, and my self-esteem was disappearing,” he admits.

Initially, he suffered in silence. “At first, I simply didn’t believe that I was depressed. My wife, Mary, did, but I didn’t.” he says. “I eventually reached out to friends who had been through depression. And I talked to my general practitioner, who said, Mike, you don’t want to let the word get out that you are depressed. That’s bad for your image.’ But finally, I had to face up to it.”

During a recent 60 Minutes special retrospective on his career, Wallace publicly acknowledged for the first time that he tried to commit suicide, alluding to taking an excess of pills.

With no traceable family history of mental illness, Wallace found himself in unknown territory. Fortunately, with the support of his wife and family, as well as the guidance and humor of good friends (Art Buchwald and novelist Bill Styron, to name just two), he survived. Wallace admits that “Anyone who says that they don’t have suicidal thoughts, if clinically depressed, is a liar.” says the candid correspondent. “Of course you do.”

The journey back from the brink was at times bumpy and included use of antidepressant therapy. “The medication kicked in after about three or four weeks.” Wallace recalls. “But as soon as the general

withdrew the lawsuit, in effect acknowledging what was said was accurate, I thought, I am fine. I’m going to play tennis. A couple of months later, however, I busted my wrist playing tennis with Art Buchwald.

And I was back in depression as deep as the first time.”

Fortunately, new therapies had emerged, and his physician prescribed one of the newer SSRIs, which slowly began to lift the black mood.

“When depressed, a day seems like a month,” he candidly states. “I am not kidding. I was told that it could take several weeks to take hold. I thought to myself, I don’t know what in the hell to do.”

Ever the professional, Wallace went to Beirut to cover a story.

“I was in a hotel looking down on the old city of Beirut, and I woke up one morning and wondered, ‘Is it possible that the medication has finally taken hold?’ I didn’t believe it, but in fact, it had,” Wallace recalls, “From that day to this. I haven’t had a tremor of depression.”

Wallace remains on medication. By sharing his courageous journey with others, he hopes to counter the stigma associated with the disease. “There’s nothing—repeat, nothing—to be ashamed of when you’re going

through a depression.” he said during a recent CBS Cares interview. “If you get help, the chances of your licking it are really good. But, you have to get yourself onto a safe path.”

For Wallace, the path to recovery included the company of two good friends—whom he calls his “blues brothers.”

“Art Buchwald and Bill Styron helped me tremendously.” he told the Post. “Artie Buchwald stayed in touch with me every night—no matter where I was in the world, but particularly in this country—to listen to my complaints and talk me through it. He did the same thing with Styron. He had to listen to the same bullshit over and over—and over—again and never complained. He was the best friend a man could have.”

Wallace also knows that suicide is all too common among seniors suffering from depression. After all, he almost became a statistic. By stepping forward, he also hopes to educate others about the disease. “You get the feeling that by now everybody knows about depression,” he stresses. “But the fact of the matter is, that is not true. Get to a psychiatrist who has the capacity to prescribe medication. Follow the suggestions of the doctor and stay on the meds! Depression can be treated. It is proven. It has been proven to me. The last 20 years have been the best of my life.”

The 88-year-old may be retiring from full-time correspondent duties, but don’t be too surprised if you see the tenacious interviewer on air. Retirement doesn’t appear to be an operative word in his vast vocabulary.

“I keep talking about it, but I keep taking on chores,” he admits. “I would just as soon die with my boots on.”