When Art Could Shock

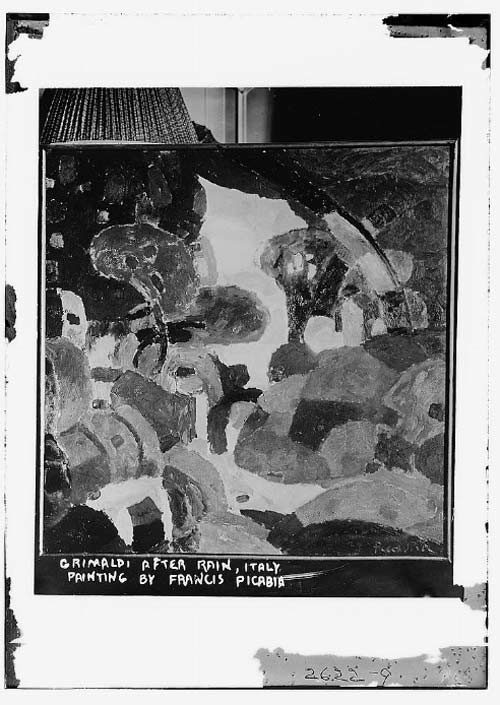

As visitors made their way into the art exhibition at the National Guard 69th Regiment Armory in New York 105 years ago, they passed through several partitioned rooms of sensible, American pieces before reaching the “chamber of horrors” in the back left corner. This was the room featuring cubist works of Marcel Duchamp, Albert Gleizes, and Jacques Villon, among others.

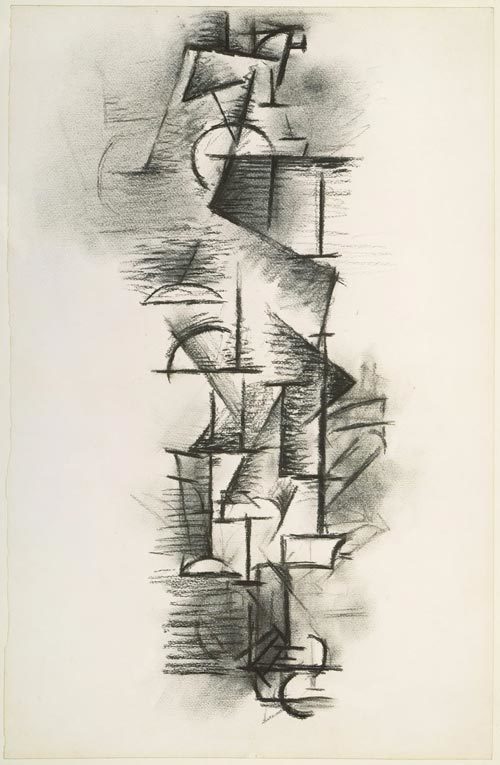

In the far corner of the cubist room was Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2. Inspired by time-lapse photography and new, avant-garde ideas of understanding time and space in art, Nude didn’t appear to resemble a nude at all, but rather an explosion. The painting delivered a cultural blow to the sensitivities of American art enthusiasts and became emblematic of the Armory Show’s legacy. American Art News lampooned the painting, offering 10 dollars to anyone who could “find the lady” in its mess of lines and shapes. Perhaps Duchamp had the last laugh when the piece sold for 324 dollars (about 7,800 dollars in today’s money).

The 1913 Armory Show — also known as the International Exhibition of Modern Art — is considered the single most influential event in American modern art, completely disrupting the conservative tastes of early twentieth-century America. About 1,200 paintings were involved in the exhibition, two-thirds of which were the experimental stylings of Europe’s flourishing modernist movement.

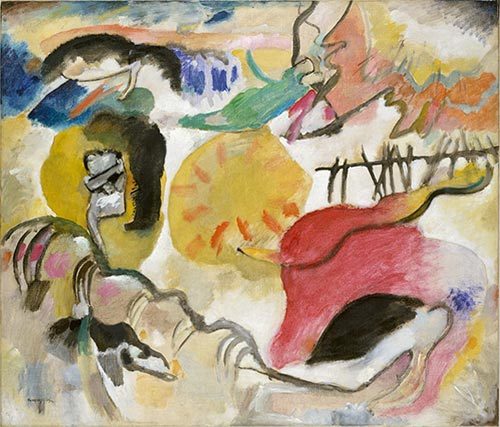

The real fun began at the exhibition’s next stop, in Chicago, where the amount of attendees was more than double that of New York. “I assert that Matisse is an impostor,” said an art historian from the University of Chicago, “that his pictures are lacking in all elements of true art, and that the cubists are just exactly nothing.” Students from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago held a protest, burning reproductions of Matisse works on the street in effigy. The Fauvist works of Henri Matisse — particularly his nudes — were appalling to conservatives in their tendency to abstract the human form and replace skin tones with bright colors.

It would now be difficult for an art exhibition to elicit the same amount of shock and controversy. Dr. Jeff Hughes, a professor of art history and criticism at Webster University, says “it would be almost impossible to experience anything as new” in our current media environment “because we don’t experience it together.” In 1913, there was no television or color photography to bring these forward-thinking European movements to Americans in any significant way.

It’s no secret that the cultural conservatism of the U.S. differed greatly from Western Europe at the turn of the century, and this was reflected in the art world. Dr. Hughes attributes this to “a built-in notion in the Protestant work ethic that making art is not real work.” Part of the legacy of the Armory Show is that it was a large, international exhibition. International shows of this scope were uncommon at the time in Europe, and certainly in America, according to Dr. Hughes.

In 2014, art critic Jed Perl wrote of the show, in The New Republic, that “the conservatives lost. The avant-garde won. End of story.” Plenty of art movements since 1913 have caused a stir, like the postwar abstract expressionists or the pop art of the ’50s and ’60s. However, the Armory Show, arguably, launched an arc in American art in which these styles could have an audience.

In the years after the exhibition, the country went to war, women won their right to vote, and Hollywood began churning out motion pictures. Duchamp, Picasso, and Matisse may have been an unwelcome shock, but the Armory Show was only a taste of the cultural changes to come.