How to Look at a Norman Rockwell Picture: Part 4 — Building on the Work of Other Greats

Read all of art critic David Apatoff’s columns here.

This is the fourth in a series of columns on how to appreciate the artistic side of Norman Rockwell. See Part 1 on Rockwell’s use of hands, Part 2 on his use of black and white, and Part 3 on how he leads your eye.

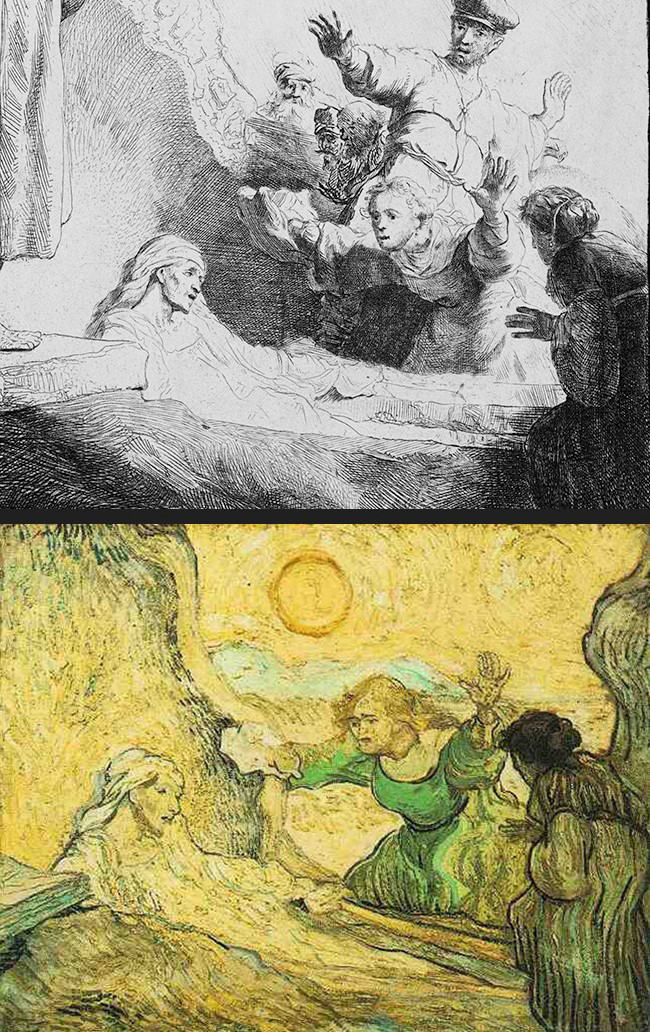

The greatest artists sometimes painted their own version of another artist’s work. For example, Vincent Van Gogh admired Rembrandt’s 1632 picture of Lazarus Rising From the Dead, so in 1890 he recreated Rembrandt’s picture as an homage:

Similarly, surrealist painter Salvador Dali took Vermeer’s painting “The Lace Maker” as his inspiration.

Norman Rockwell was no different. He was inspired by the greatest artistic geniuses and felt challenged by their accomplishments. Even though he was a “mere illustrator” he felt he could learn important lessons from their work. If we recognize these influences in Rockwell’s work, we can better appreciate the scope of his ambition.

For example, Rockwell’s 1943 cover illustration of Rosie the Riveter was a direct tribute to Michelangelo’s famous painting of the prophet Isaiah on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel:

Similarly, when Rockwell wanted to paint a picture of murdered civil rights workers he used as his model Manet’s famous composition of a fallen matador:

And Rockwell said that his model for this urban street scene for the cover of The Saturday Evening Post was Vermeer’s famous painting, “The Little Street in Delft.”

Why do artists use the work of other artists? Is that cheating? Have they run out of ideas?

If we take a closer look at Rockwell’s painting of the street scene, it will give us a better idea of what Rockwell is doing.

First we should note that this painting exemplifies everything that fans love about Rockwell. The story it tells is rich, interesting and multi-layered.

A family walking to church on Sunday morning, all dressed up with stiff — perhaps overly stiff — postures, averts their eyes from the seedy neighborhood through which they must walk. Notice that the milk bottles and Sunday morning newspapers are still on the front porches, so the local residents are still in bed. A pair of dancing shoes from the night before is airing out on a window ledge. For an especially nice touch, notice the flock of birds in the sky leaving the steeple, roused by the ringing of the morning church bells.

Go down an additional layer into this painting and you’ll realize that it describes how critics thought of Rockwell. They accused him of being myopic, his eyes fixed straight ahead, disregarding the seamy side of life all around him. True artists are supposed to notice details such as litter and broken sidewalks, but Rockwell was accused of living in a corny, idealized world.

But consider this: Rockwell’s tribute to Vermeer was painted at the exact same size as Vermeer’s masterpiece, using the exact same medium, and it comes off well by comparison. Rockwell may have been working on a deadline for a corporate employer, but he aimed high. He painted those bricks, captured the glow and the feel of old Dutch painting, studied Vermeer’s palette and composition. He appreciated Vermeer’s artistry and was able to work in that style the way very few, if any, fine artists of his day could. He may not have viewed himself as an artistic genius, but we can tell from his choices that he viewed the work of artistic geniuses as relevant to what he was doing.

Featured image: ©SEPS