The Art of the Post: How Magazines Revolutionized the Art World

We are pleased to introduce the first of a biweekly column on art and illustration by art critic and historian David Apatoff. David will share exciting and interesting illustrations, reveal colorful stories about Post artists and their methods, and offer insights into why art and illustration are such an important part of our culture. We hope you enjoy it!

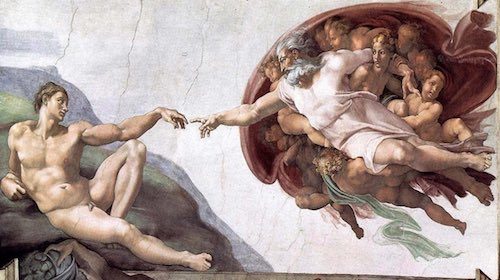

For 10,000 years, artists were hired by the wealthy and powerful. Kings, priests, pharaohs, and popes commissioned art for cathedrals, palace walls, sacred caves, and public spaces.

Then, gradually, this market for art faded away. Kings began to vanish from the Earth; churches stopped commissioning altar paintings and chapel ceilings; princes no longer hired artists for flattering portraits or murals of glorious military victories. Their castles were handed over to public trusts in exchange for tax deductions.

Artists had to find new places to sell their art.

Fortunately, a new breed of sponsor arose to replace those historical patrons of the arts. The growth of capitalism and the invention of the corporation gave private citizens the wealth to commission art. Businesses began purchasing “commercial art.” Even more importantly, new technologies for mass-producing pictures and distributing them to wide audiences enabled working families — whether rich or poor — to enjoy great art in their homes. Rather than compete to become a royal painter, artists could now publish millions of copies of a picture and sell them to large numbers of customers for pennies apiece.

In the 19th century, The Saturday Evening Post was one of a small handful of American magazines, along with Harper’s Weekly, Century, and Life, that were densely printed black-and-white periodicals with wood engravings for illustrations.

By the 20th century, the magazine industry had blossomed into dozens of popular and well-designed color periodicals. Historians have dubbed this the “magazine revolution.” The quality of reproductions, and the newly sophisticated vehicles for delivering them to the public, transformed the economics of art and inspired new bursts of creativity. Public enthusiasm for new pictures grew dramatically as technology for reproducing pictures in magazines improved.

The Post soon became the most widely circulated magazine in America. This was largely due to editor George Lorimer’s vision of taking advantage of the newly available technologies for printing images.

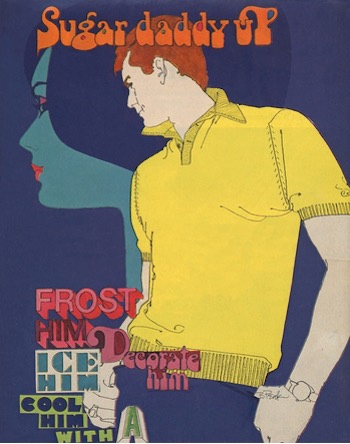

The most talented artists learned they could become wealthy by creating pictures for the new mass audiences. Illustrators such as Norman Rockwell, Maxfield Parrish, J.C. Leyendecker, and Charles Dana Gibson received handsome sums illustrating magazines. Their covers became a popular topic of conversation across the country. The art inside the magazines — ranging from story illustrations to imaginative advertisement pictures — shaped popular taste, too.

Several of the images created by these illustrators became cultural icons. In this way, the modern magazine became one of the world’s greatest platforms for art.

Great painters of the era aspired to be magazine illustrators. In letters to his brother, Vincent van Gogh praised the quality of illustrations in magazines such as Harper’s Weekly and Illustrated London News, and he clipped out their drawings and pasted them in portfolios for further study. The great abstract expressionist Willem de Kooning came to America to become a commercial artist.

As the technologies continued to evolve, the next generation of illustrators was able to make images that moved and spoke. At animation studios such as Disney and Pixar, they painted with computers rather than brushes. Today, illustrators are pioneers in computer games employing virtual reality. But no matter how advanced the technologies become, illustrators continue to look back and gain inspiration from their artistic roots in magazine illustration.

With all these changes in the landscape of art, it’s fair to ask: Who was the greatest art patron of the 20th century? If we measure by the size of the audience and the influence of the art, one good candidate is The Saturday Evening Post.

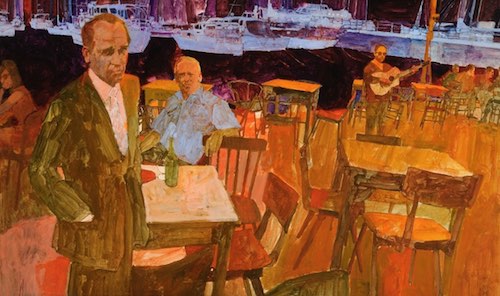

The Post’s circulation in the first half of the 20th century was far greater than the audience enjoyed by any museum or private collection of the period. Every week, the Post delivered a cornucopia of pictures, not just to audiences in big cities but to people in small towns with no museums, libraries, or televisions. Many of its illustrators recognized this fact and took their artistic obligations seriously. Post illustrator Robert Fawcett said, “We represent the only view of art and beauty that millions of people get a chance to see. If we do less than our best, we cheat them.”

For many years, the weekly audience for the Post was larger than the audience for Picasso, Matisse, or any other giants of 20th century modern art. Furthermore, the art in the Post’s illustrations had more of an impact on day-to-day lives, shaping cultural identity and political beliefs in ways that museum artists never did. They drove consumer choices, sold war bonds, persuaded young men to join the army (“Uncle Sam Wants You!”), and affected our standards of beauty, patriotism, love, and ethics. And as Lionello Venturi, the foremost historian of art criticism, has pointed out, “What ultimately matters in art is not the canvas, the hue of oil or tempera, the anatomical structure and all the other measurable items, but its contribution to our life, its suggestions to our sensations, feeling and imagination.”

Several fine art critics of the 20th century have argued that in order to be accessible to a wider audience, illustrators sacrificed avant garde art principles, making illustration a lesser art form. But the passage of time has caused experts to re-examine that view. Today, illustration is increasingly respected by museums, academics, and collectors. Meanwhile, so-called “fine” art is viewed by many as esoteric, self-absorbed, and irrelevant. Noted writer and art critic Tom Wolfe said in a speech at the National Museum of American Illustration, “I feel very comfortable predicting that art historians 50 years from now … will look back upon illustrators as the great American artists of the second half of the 20th century.”

As Shakespeare proved, broad appeal to a popular audience is not incompatible with greatness.

A wealth of 20th-century illustration lies behind us, largely unexamined and underappreciated. It is one of my great pleasures to help unearth that art and consider its qualities afresh, on a level playing field with other art forms. I hope you will join me here for an interesting ride.

Art’s Healing Powers

On any given day, landscape artist Barbara Ernst Prey is apt to find e-mails from museum curators and patrons clogging her in-box. Prey’s canvases hang on the walls of world-class institutions, in private collections, and even at the White House. But the messages that cause her voice to crack with emotion are the ones from ordinary people who write about the transforming effects her paintings have on their lives. There’s the letter, for instance, from a man recounting how his relative, suffering from Lou Gehrig’s disease, found solace in Prey’s paintings. “When he was ill and in a wheelchair, he lined up my paintings on a long mantelpiece so he could just look at them and enjoy them,” Prey says.

Prey is a creator of beautiful things. Among her works is a painting of the Space Shuttle Columbia lift-off commissioned by NASA as a tribute to the families of the astronauts who lost their lives in the disaster. Her images soften life’s blows.

Art has that kind of healing effect. Turns out what’s on the wall is a lot more than a statement of style. Medical experts say it can change a person’s physiology, alter perceptions, and have a calming, curative influence. And they knew it even before they could prove it. In 1860, Florence Nightingale wrote about the effect of “beautiful objects” on sickness and recovery. “Little as we know about the way in which we are affected by form, by color and light, we do know this, that they have an actual physical effect.”

In the early 20th century, medical advancements progressed at such a rapid clip, the human factor became secondary to technology. Modern hospitals were sterile, sleek and stark. Then in the 1940s, the curious new field of art therapy came into its own, advancing the notion that art-making could be used to improve and enhance one’s physical, mental and emotional well-being. Conventional medicine remained skeptical until the results became too compelling to ignore, and that’s only been in the past 20 years, says Dr. Brent Bauer, director of the Complementary and Integrative Medicine Program at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. Adjunct treatments like art therapy that were once considered “weird” are now being welcomed. “If looking at a beautiful picture in a room or having access to art-making helps an individual get through a difficult day or a difficult procedure, it’s getting harder and harder not to be excited about it,” Bauer says, “It’s a fun time of medicine.”

These days, studies are drilling down on the mind-body connection, and the mounting evidence of art’s therapeutic benefits is indisputable. Art helps ailing children gain some control over their helplessness. It reduces pain in cancer patients. It helps Alzheimer’s patients develop a new language of communication and combat memory loss. The Museum of Modern Art in New York hosts a free monthly program for Alzheimer’s patients in which its vast collection of modern masters is used as a platform for mental stimulation.

Mayo Clinic launched a pilot program among men and women battling such serious diseases as leukemia, lymphoma and multiple myeloma, many of whom were in hospital isolation. “The idea was to bring something to the bedside that could help improve their quality of life and reduce stress,” says Bauer. That something was art. “Without even trying to be therapeutic, in many cases it was. We were looking at their pain, their mood. If it was negative, could we improve it? If it was positive, could we enhance it?” The answer was an unequivocal yes. And to Bauer’s surprise, the findings crossed over “gender and age and all things I thought might have been barriers.” Bauer says the trial revealed a “trend toward improvement in pain” and “significant improvements” in mood and anxiety reduction.

alzheimer.jpg“When we reduce stress, we improve sleep and we improve the immune system,” Bauer explains. Mayo has received benefactor support to expand the program.

Art history and art-making workshops are a regular part of the schedule offered at Hewlett House, a cancer-support resource center on Long Island. Eileen P. McCarthy has been a regular since she was diagnosed with her third bout of breast cancer in 2005. “Cancer can be in your mind 24/7,” says McCarthy. “Art pushes all that aside.” Not long ago she was painting a beach scene when her instructor, Laura Bollet, came up beside her and asked McCarthy what was the matter. “The calm sea I was painting was suddenly a storm. I didn’t even realize it but it made me grasp how upset I was. It had been all bottled up. I couldn’t get my ocean to calm.” Bollet says the canvas was capturing emotions before McCarthy had a chance to articulate them. The woman who once told a family member she couldn’t draw a straight line with a ruler now says art has “become a part of my life. It’s an amazing medium. I was surprised at how far I’ve gone and how far it’s helped me.”

The simple act of enjoying a work of art can be just what the doctor ordered. The University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor has an “Art Cart” program, a kind of lending library of framed poster art. Volunteers go room to room allowing patients to select artwork that connects with them personally to hang on their walls.

As an artist, Barbara Prey says, “It’s very touching to see how your work is used in ways you just don’t know. And it’s rewarding to know I’ve done something that’s made someone’s life a little better.”

Trying to figure out what art is the right prescription for health and healing is, as you might expect, in the eye of the beholder. One man’s Norman Rockwell is another man’s Jackson Pollock.

The_Simple_Life.jpgBauer says landscape scenes have shown promise in studies. “We’re wired to enjoy nature.” According to Bauer, patients in hospital rooms that face woods and trees do better than those in rooms facing, say, a brick wall, which explains why so many medical offices and hospitals are adorned with pictures of the great outdoors. “If you’re going to have a tube placed in your stomach, a fairly uncomfortable procedure, and you can stare at a beautiful scene of a mountain or an ocean, it reduces stress and makes the procedure easier,” Bauer says.

For some, familiar images can spark an emotional connection and release a memory that generates positive feelings. Others get that reassurance by staring at pictures of large color fields or religious iconography.

“Art-making or the act of creating involves every single part of the brain,” says art therapist Elizabeth Cockey of Levindale Hebrew Geriatric Center in Baltimore and author of the memoir Drawn from Memory (2007). “It stimulates our neurology, and that feels good.”

Cockey ticks off a list of restorative benefits she’s seen as a result of her work, even in her lowest functioning patients: alleviation of depression, enhanced hand-eye coordination, improved motor coordination leading to more independence, and the restoration of self-esteem. When individuals engage in art-making, they realize, “there’s more to life than their own circumstances.”

Hewlett_House.jpgHer experience is backed up by a report released by the National Endowment for the Arts on the impact of arts programs on older Americans. The study found that seniors who participate in weekly arts programs reported better health, fewer doctor visits, and less medication usage than those who don’t.

Julie Gant is an art therapist who works with patients at the other end of the spectrum at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. Art is used to help kids as young as two and three offset hopelessness. “There are so many things kids don’t have choices about — surgery, medical procedures, even blood pressure takings — that getting the chance to make choices instead of passively lying in bed counteracts feeling of helplessness,” she says. The choices may be as simple as what colors to select or what materials to use, but if youngsters can pick up a pencil or a crayon, they can take an active role in creating. “It’s a chance for them to make choices in an environment where their choices are limited.”

Art is such a natural part of kids’ lives that it helps normalize their strange and difficult surroundings and distract them from pain or side effects of medication. Gant says that for youngsters who haven’t had a chance to process what’s happened to them, art can help stave off post-traumatic stress syndrome and other related woes. “Art helps them make sense of their situation.” What’s more, it’s a vehicle to communicate emotions they may not be able to articulate. Drawing something might be easier for a first-grader than talking about it.

In the meantime, Eileen McCarthy says she is winning her battle with cancer. “I would not have gotten through this without the art course at Hewlett House. Art has helped as much as any medication.”

That’s no surprise to folks like Elizabeth Cockey. “The truth is, art makes you better. It doesn’t happen overnight. And not everybody is going to get better in the same way or in the same time frame. But it will happen.”