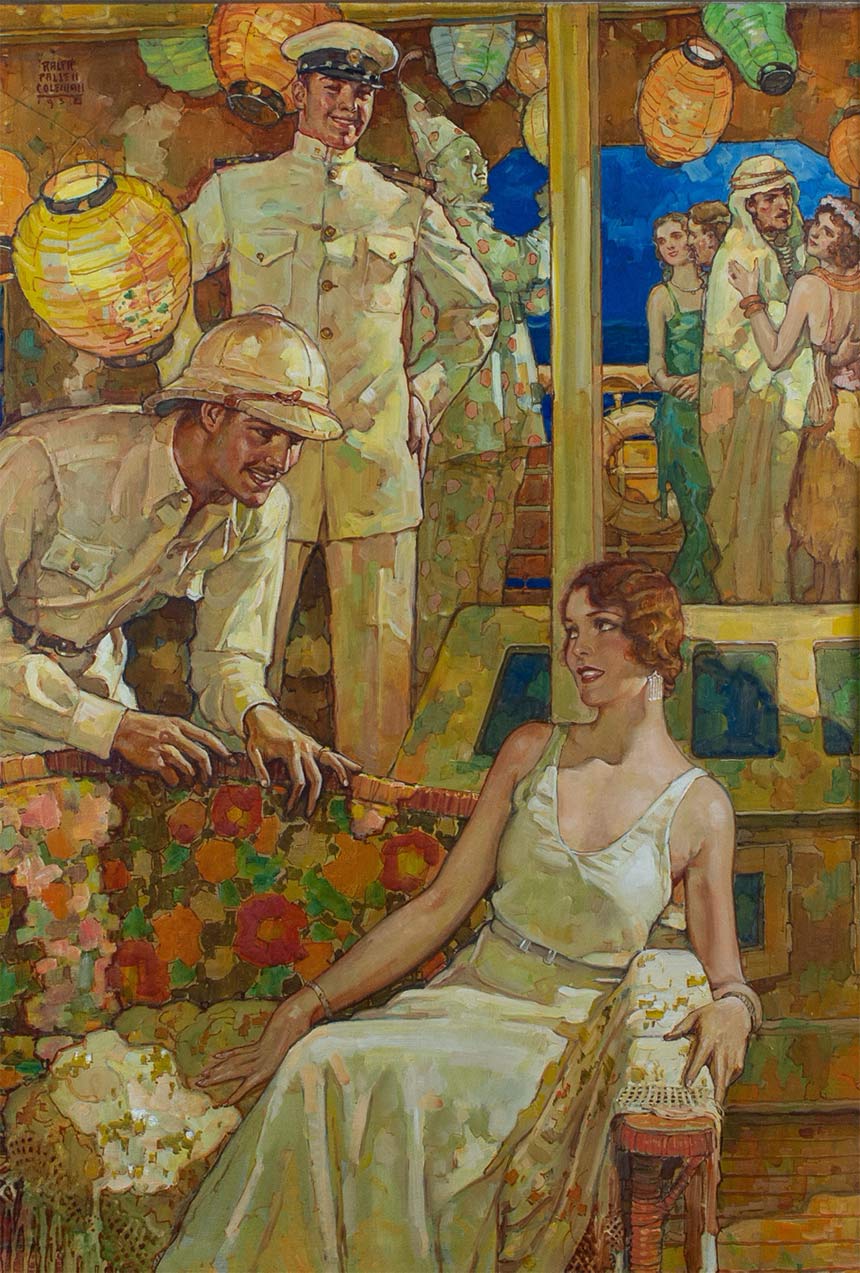

The Art of the Post: The Artist Who Painted Paradise

Read all of art critic David Apatoff’s columns here.

During the Golden Age of Illustration, magazine readers loved stories about romance and adventure beneath a tropical moon.

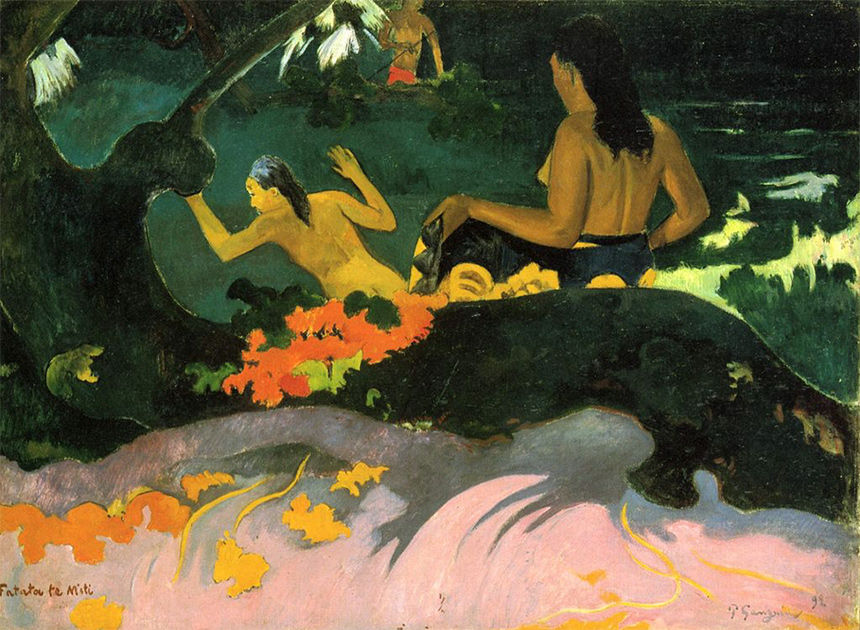

The urge to flee civilization for a South Sea paradise actually dates back to the 19th century when the famous French painter Paul Gauguin rebelled against what he viewed as the corruption and pollution of industrialized Europe. Gauguin abandoned everything — including his country, his wife and children — to move to Tahiti. His colorful paintings of half nude native women in bright sarongs on pink sand fueled the imaginations of the office workers and city dwellers back home.

Years later during the Great Depression, Americans — including readers of the Post — shared similar fantasies about a trouble-free paradise where you could pick fruit from a nearby tree and frolic in the surf.

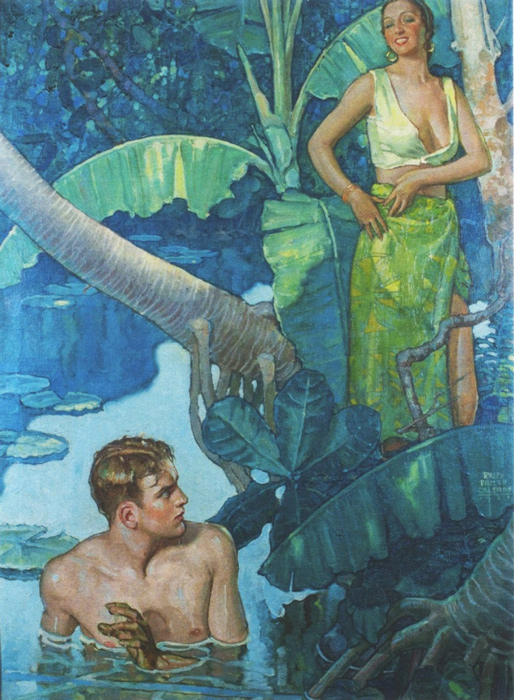

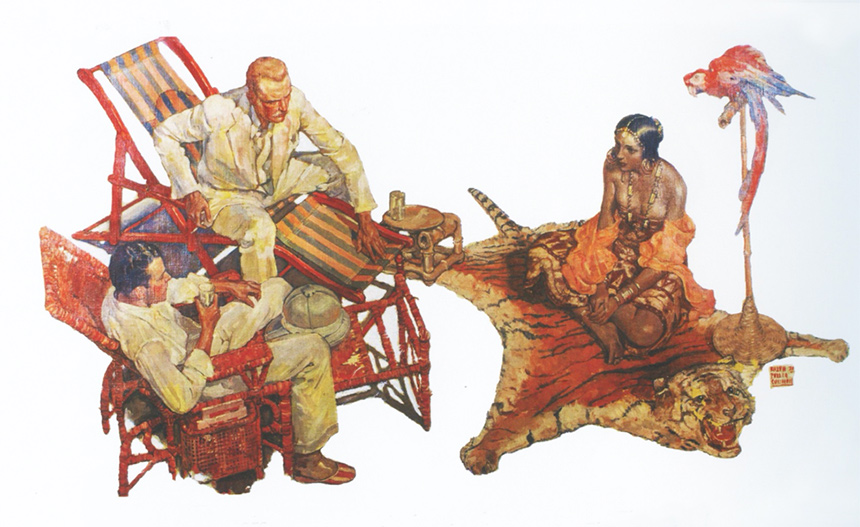

Ralph Pallen Coleman (1892-1968), an illustrator for the Post and other magazines during the Golden age of illustration, was acclaimed for his illustrations of such fantasies.

Far from being a world traveler, Coleman was born and grew up around Philadelphia and lived there all his life. The closest he ever got to a Pacific island was National Geographic magazine, whose photos he used for reference.

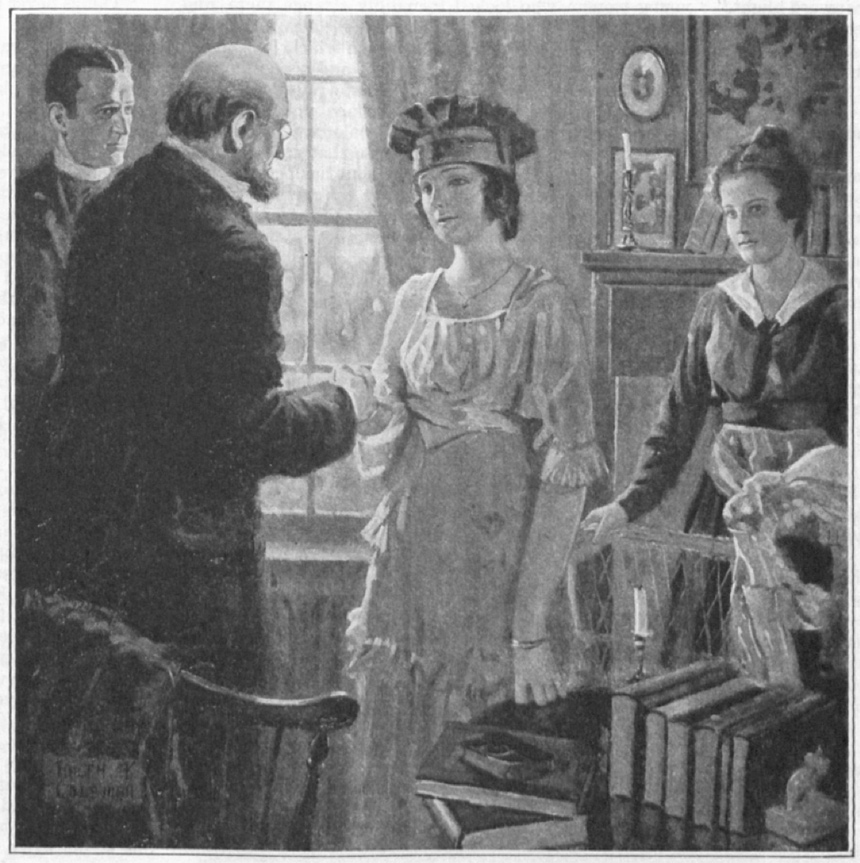

A precocious artist, Coleman left art school early at age 21 and set up a studio on Walnut Street, just across from the offices of the Post. Like other artists he had a slow time getting started in the highly competitive field of illustration. His first sale, to the American Sunday School Union, netted him a grand total of $7.50. But he worked hard and within two years, he had sold his first illustration to the Post: an illustration for the story, “The Fairview Girl Crop.”

However, by 1917 he was receiving steady assignments and felt secure enough to marry Florence L Haeberle, also of Philadelphia.

Coleman continued to work for the Post and other magazines well into the depression years. He illustrated stories by some of the world’s most famous authors, including F. Scott Fitzgerald, W. Somerset Maugham and Booth Tarkington. He painted a wide range of subjects, but he became best known for his illustrations of exotic locales. His palette captured the sultry climates, bright colors, and rich vegetation of tropical islands.

Most readers in that era would never end up traveling overseas — they would stay close to home, raise their children, mow the lawn, and wash the dishes. Perhaps in another lifetime they might go skinny dipping in a jasmine scented pond surrounded by brilliantly plumed songbirds. But in this life, the evocative stories in the Post and other magazines was as close as they would ever come.

Despite the fact that Coleman himself never visited any of these locations, in many ways his illustrations were more realistic than the paintings of Gauguin, who lived on a Pacific island for years. Despite the fact that Coleman was a highly devoted Presbyterian and a trustee of his church, his illustrations managed to capture the spirit of pagan rituals. It just goes to show that even when an artist never strays far from home, the artistic imagination can take viewers on long, vivid trips.

In 1942 Coleman left the field of illustration to devote the second half of his life to religious paintings. Between 1942 and 1968 he painted 400 pictures about the life of Jesus and the Bible. These paintings became extremely popular within the Christian community. His series on the life of Christ was converted to stained-glass windows for Grace Presbyterian Church.

This might seem like a dramatic break from Coleman’s earlier paintings of South Sea islands. On the other hand, perhaps Coleman was just painting a different kind of paradise.

Featured image: Illustration by Ralph Pallen Coleman (courtesy of RAPACO Corp.)

Cartoons: Snow Woes

“I might be interested. Here — c’mon in and see me”

February 3, 1940

“Odd how old, forgotten words spring to mind, isn’t it?”

December 27, 1941

“Quick freeze, wasn’t it?”

December 16, 1944

“I’ve told him a thousand times he can’t go into the house with his shoes on.”

December 01, 1945

“You’ll find the shovel under the cellar stairs.”

December 29, 1945

November 01, 2002

“That was close.”

January 01, 1955