America’s Last Massive Immigration Ban: 100 Years Ago

One hundred years ago, the U.S. Senate passed a law that put unprecedented restrictions on immigration to America.

One hundred years ago, the U.S. Senate passed a law that put unprecedented restrictions on immigration to America.

The Immigration Act of 1917, which passed despite President Wilson’s veto, introduced three major hurdles to aliens. First was a long list of characteristics that would disqualify immigrants from entry:

…all idiots, imbeciles, feeble-minded persons, epileptics, insane persons; persons who have had one or more attacks of insanity at any time previously; persons of constitutional psychopathic inferiority [homosexuals]; persons with chronic alcoholism; paupers; professional beggars; vagrants; persons afflicted with tuberculosis in any form or with a loathsome or dangerous contagious disease … persons who have been convicted of, or admit having committed, a felony or other crime or misdemeanor involving moral turpitude; polygamists, or persons who practice polygamy or believe in or advocate the practice of polygamy; anarchists, or persons who believe in or advocate the overthrow by force or violence of the Government of the United States.”

Second, the fortunate candidate who avoided falling into any of these categories would next meet a literacy test. Any alien over the age of 16 had to read 30 to 40 words in the language of their choice — English was not required. Interestingly, immigration authorities could exempt aliens from the literacy requirement if they were seeking asylum from religious persecution.

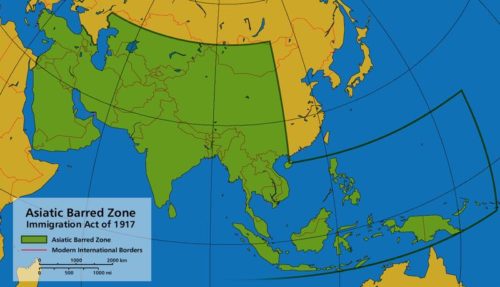

Third, the Immigration Act imposed a blockade on any immigrants from the Asiatic Barred Zone, a rule with parallels to President Trump’s executive order banning travel from seven Muslim-majority countries for 90 days.

This barrier stretched across the globe from the Pacific to the Mediterranean. Immigrants would not be admitted from Polynesian islands, Southeast Asia, India, southern Russia, or any middle-eastern country up to the banks of the Suez Canal.

There were several motives behind the law. One was Americans’ resentment of Asian immigrants, who would work for lower wages than white employees. The rising number of Chinese and Japanese immigrants played on Americans’ fears that U.S. culture was being replaced by foreign influences. The fear and resentment of Asian immigrants grew over generations into something called “The Yellow Peril,” which cast Asia as a threat to Anglo-Saxon civilization.

The Post wasn’t buying any of it. And it used the occasion of a 1904 editorial to puncture the paranoia that is always so easily stirred by demagogues.

The “Yellow Peril” Again

All our truly great journalists, statesmen, and volunteer thinkers agree upon the existence of the “yellow peril”; but they radically disagree as to what the yellow peril is.

Some hold that the triumphant Japanese will set the teeming millions of the Orient at work manufacturing cheap goods with which they will flood the Occident. Others hold that the yellow peril is military — the Japanese arming the teeming millions aforesaid and flinging them upon the Occident in such wars as those that submerged ancient Rome.

Happily, both perils cannot coexist. If the teeming Orient millions are at home manufacturing cheap goods they cannot be away from home making war. Further to allay fear, if the Orient sends forth floods of cheap goods the millions of buyers of those goods will, at least, survive the inundation — else, how could goods be sold? Finally, if Japan means civilization—and who now doubts that she does? — then she does not mean war; for civilization means peace, except in the minds of boy-men, who remain forever at the blood-and-thunder-novel stage of life.

“Yellow peril” is not a bad subject for debating societies; but as a serious proposition it ranks with a pumpkin-shell with eyes, nose, and mouth cut in it and a candle inside.

Editorial, July 30, 1904

The law was also spurred by a fear that a flood of immigrants, fleeing the European war, would sweep into the U.S. In an editorial published a month after the law’s passage, the Post editors predicted immigration would continue at the high levels seen from 1912 to 1914.

Immigration

As against the theory that immigration would be of negligible proportions for many years after the war, even if we put no restrictions upon it, the fact that our net gain in alien population in 1916 was greater than in 1914 may have some significance. As compared with 1915 the number of immigrants increased by a hundred thousand in spite of all the obstacles raised by a second year of war, while the number of aliens departing from the country was smaller than in the year before by over a hundred thousand.

Departures, in fact, were but little over one-fourth the average for 1912, 1913, and 1914. If any inference can be drawn from decidedly increased arrivals and decreased departures in the second year of war it is not that immigration after the war will be negligible.

But if we assume that immigration will be negligible for many years, to say that we will admit only those who on the whole are most likely to make desirable additions to the population is still sound principle. It overthrows the theory that we are morally bound to hold an open door for whoever seeks residence here — a theory which, in fact, we have never practiced, for we have always put restrictions upon immigration.

Editorial, March 17, 1917

But the war-refugee flood never came. Total immigration dropped from 1.2 million in 1914 to 316,700 the following year, and didn’t rise above this number for the next seven years.

The 1917 Immigration Act remained on the books until 1952, when it was replaced by the McCarran-Walter Act, which finally allowed immigrants from the Asiatic Barred Zone to become naturalized citizens.

Featured image: Shutterstock