North Country Girl: Chapter 55 —A Chicago Courtship

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

The best advice my mother ever gave me was, “Don’t get involved with anyone who has more problems than you do.” After James, with his morbid fear of gaining weight and getting old, who detested the idea of marriage and who had rejected his own child twice, who had lost his fortune and then his mind, I was determined to go out only with normal, problem-less men. Yet the next guy I dated turned out to have an unsavory fetish and a brain-damaged daughter. And Michael Trossman, an artist who flirted with me at a drug-soaked party, had an ex-wife, two kids, and a very complicated love life. Count me out, I thought. But work and loneliness and life conspired to bring me back to Michael and his bohemian digs at 155 Burton Place. A week after the MDA party where Michael and I met, Ann Geddes called me.

“You’ve got a booking at Oui, if you want it. It’s fully clothed, and it’s for promotional material, not anything in the magazine. I think you should take it.”

Oui was a Playboy publication, part of that great empire that devoured pretty young women who were desperate for money or fame. It was meant to appeal to younger readers, guys who grew up sneaking looks at their dad’s not-carefully-enough-hidden collection of Playboys, and who might otherwise be lured over to the more explicit Penthouse magazine.

Playboy’s Playmates were supposed to look like the girl next door if she ran around naked. The Playmates were posed cuddling a puppy or looking at a daisy; you couldn’t tell if they were getting ready to have sex or to bake cookies.

Oui ran racier photos of real and fake European girls, on the assumption that European equals sophistication equals hotter in the sack, girls wearing nothing but wooden shoes or holding a strategically placed baguette. Oui had no investigative journalism, no high-brow fiction, no interviews with presidents and movie stars. It was just pages and pages of sultry, nude women in berets interspersed with arch, sarcastic humor, painfully modeled after National Lampoon and falling short, and sensational, often fraudulent, articles such as “Is This the Man Who Ate Michael Rockefeller?”

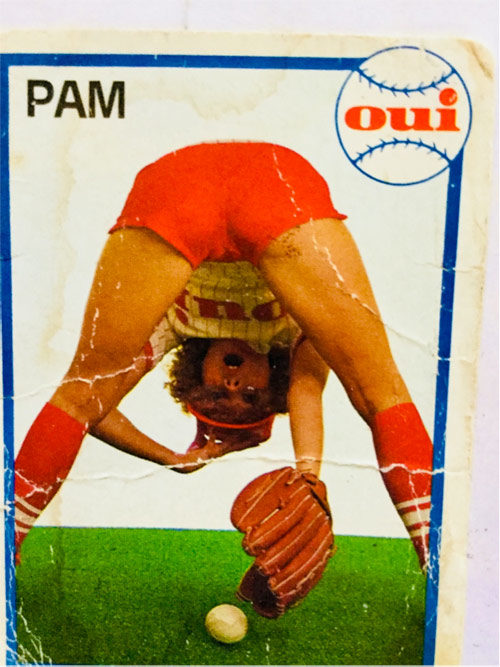

My modeling job for Oui was to pose as the shortstop on an imaginary Oui all-girl baseball team. My uniform was a white and red pinstriped, deeply V-necked shirt and frighteningly small shorts that struggled to cover my butt.

It was my new pal George who handed me my baseball outfit and mitt. He had just been transferred from Playboy to Oui, where he was now the creative director. George had specifically requested me for this shoot.

Oh crap, I thought, here’s a guy who has already seen me naked, given me drugs. I was pretty sure where this was going and I pondered how to keep George at arm’s length and still be the nice, obliging model he would want to book again.

But George was all business in the photo studio, with the exception of darkroom pot breaks. There was not even flirtatious banter. When George came over to pose me, instead of doing it by placing one hand on a breast, the other on my butt like every other photographer did, he held me gently by the elbow.

First I stood with a baseball bat cocked on my shoulder while the photographer shot me from above. George shook the Polaroid, shook his head, probably at the unremarkable view down the front of my shirt, and then repositioned me. I bent over from the waist, baseball mitt on the patch of Astroturf, waiting for that groundball, my upside down face in an idiotic grin and my tight, tiny shorts riding even farther up my behind. George yelled “That’s it!” and we were done.

While signing my modeling voucher, George said, “Oh, we’re having a barbecue tonight, why don’t you come?”

I had planned to go home to my un-air-conditioned apartment, feed Groucho, my dog, drink copious amounts of iced tea, and read a book. But free food, free drinks, free drugs, pretty or smart people partying in those gorgeous apartments…“George, thanks, I’d love to.”

That evening the party was on the roof, the soundtrack was Curtis Mayfield, and while thankfully there was no MDA, the pot was strong. I climbed the ornate cast iron spiral stairs, which wobbled beneath me, and was greeted by a modest view of Chicago’s Near North neighborhood on one side, on the other the Cabrini Green housing project, as scary as Tolkien’s towers. Above this mundane cityscape stretched a twilight sky streaked with Technicolor reds and yellows in the west, deepening in the east to violet blue punctuated with a single star.

George escorted me over to Michael Trossman, who twinkled like that lone star. “The sky looks like a Maxfield Parrish,” I said.

“I knew you guys would get along,” said George proudly. Michael, the incurable romantic, had fallen out of love with Fred’s wife and in love with me.

“I can’t believe you’re a Playboy model,” Michael said. This, although technically true, required narrating my life story over several beers, hot dogs, and joints, a tale that featured how I had landed in Chicago, swept off my feet by James Rodgers.

When I was finished, Michael looked discouraged. “I’m not rich. I make art. It’s hard for me to come up with money for my kids each month.” The unspoken accusation of gold-digging stung. If I were a gold-digger I was the world’s worst: the only gold I had dug in my two years with James was the flimsy GAY pendant about my neck, one bracelet with a clasp for a promised charm that was never bought, and a chain necklace that turned out not to be gold at all.

So I let Michael kiss me. And then, in complete opposition to Anita Loos’ claim, it was just as easy to fall in love with a poor man as a rich one, although it took me a while. There was so much in Michael Trossman that reminded me of my original Michael, my first true love: the sly hidden intelligence, the European background, the moody, thin-skinned sensitivity, even though in looks he resembled him not at all: M. Trossman looked like a young Saul Bellow, M. Vlasdic like a young John Lennon.

Michael Trossman was the Romantic Artist; he had to be either madly in love or reeling from heartbreak. Just as LSD had been the philosopher’s stone that transmuted my teenage infatuation with Michael Vlasdic into a melding of souls, MDA was the elixir d’amour that sent Michael Trossman into a whirlwind of romance, buffeting him from Ronny’s girlfriend to Fred’s wife, to me, his new fixation.

After my escape from a semi-suicidal James and my refusal to play dominatrix in California, I believed I was through with men. I obviously had bad judgment or bad luck when it came to boyfriends. I was determined to spend my nights in my own bed, alone except for Groucho toothlessly drooling on my pillow. But it seems that the minute you decide you don’t want something, life insists that you do.

Michael courted me. He drew funny caricatures of me, signed “To my small girl” with XXX and OOO underneath. He was an enthusiastic amateur musician; he dragged his guitar out of the closet and sang love songs in goofy, off-key voices. Michael took me through his extensive record collection, peering up at me through his glasses to see if I liked what he liked; after years of living in a disco desert, I melted to English art rockers (Queen, Genesis, 10cc) and thrilled to the clamor and riot of punk (The Ramones, The Clash, Television). We sat close together on his couch listening to music, with the soft light beaming through the wall of translucent glass bricks, smoking pot, not needing to talk. I felt my shoulders loosening up and my heart thawing as “I’m Not in Love” filled the Art Nouveau living room.

I am most grateful to Michael for introducing me to music that had been right under my ears: the Chicago blues. Not a chorus or a chord of that soul-trembling sound had ever infiltrated my yuppie Near North enclave. Lightnin’ Hopkins, Hound Dog Taylor, Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, all alive and playing the blues just a few miles south of us, a whole new world to explore.

A few miles north of Burton Place was Wrigley Field. “I don’t really like sports,” I protested as Michael shoved me into an uptown El on a balmy September day.

Michael shook his head and kissed me and said, “But it’s the Cubs. The Cubbies! The only pro team named after a baby animal.”

As we stood in line for the bleacher seats, a man worked his way down the crowd, handed Michael a plastic razor, and muttered “Gillette Day.”

“Hey,” I sputtered. “Don’t I get a razor?”

“Um, they’re men’s razors.” That was annoying. I challenged the razor guy to describe exactly what made a razor suitable for a man but not for a woman. Why couldn’t I shave my legs with the razor he was passing out to the men? Beaten down, Mr. Gillette grudgingly handed me a razor, and flush with victory, I ordered “Make sure the rest of the women get one too,” and the three other women in line cheered. Michael congratulated me on my tiny feminist victory with a sweet nuzzle on the neck and led me out to the wonders of The Friendly Confines, Wrigley Field.

Coming up from the dim ticket area was like ascending into a different world. The sky stretched out above in an open expanse rarely seen in Chicago. The field was a lush green that every Duluth dad sowing grass seed or smearing sheep shit over his front lawn could only dream of. Across from us, stately and still unlighted, rose the grandeur of Wrigley Stadium, as noble a piece of Chicago history as the Rookery or the Museum of Science and Industry. We found places to sit in the full sun of the bleachers, and Michael pulled out a slightly grimy Cubs cap for me. “My son’s,” he apologized. I put on the cap and bought two beers in waxy cups from the vendor, and then we rose for the National Anthem.

I had yet to give my heart completely to Michael, but that day I fell in love with baseball, played as it should be, during the day, in plein air, even though the Cubs managed to blow a six-to-one lead over the Mets, much to the disgust of the raucous, filthy-mouthed, beer-soused bleacher bums around me. Michael was drinking at the rate of a beer an inning, but I slowed my own consumption after a long, winding, desperate search for the ladies’ room, which was situated as inconveniently as possible. I was sober enough to be alarmed when, in a late inning, I watched a tiny white sphere head skyward at the same time I heard the resounding crack of bat against ball. The sphere arced high and long, then plunged bleacherward as if it had been launched directly at me, getting bigger and closer until it suddenly dropped between my feet; I managed the one semi-athletic achievement of my life catching the ball on the bounce.

I started to say, “Would your kids like…” to Michael when a chorus started up: “Throw it back! Throw it back!” The offending ball had been homered by a Met. Michael shook his head, and I feebly tossed away the only baseball I have ever caught; it dropped into the ivy that enrobed the bleacher wall and may still be there to this day.

Squashed on the El with a thousand resigned Cub fans commiserating another loss, Michael teased out of me that my favorite food was Indian. That night he took me out to dinner, refusing to let me so much as leave the tip. A baseball game and dinner and I knew that he rarely spent a penny on himself, always busy hustling illustration jobs to pay rent and child support. Michael reached across the stained tablecloth and held my hand, and my heart gave an almost painful pang. How could a cheap curry and Kingfisher beer feel more romantic than champagne and steak Diane?

This was a new experience; I had never been wooed before. I made up my mind in the first 45 seconds of meeting a guy if I was going to sleep with him or not, and I had always stuck to my guns. Michael insisted that it wasn’t the MDA talking; he really had fallen in love with me. And as summer died away, the MDA parties with the rotating bedmates at Burton Place went from weekly to monthly and then never again, miraculously without any divorces, break-ups, or stabbings.

But in addition to his fun, funny, creative group of Burton Place denizens, who I adored and who seemed to like me (although maybe they were just glad to have me around since they were running out of wives and girlfriends for Michael to fall in love with), Michael had an ex-wife and two kids. His visitation schedule with his sons was erratic; sometimes he knew when they were coming, sometimes he called to warn me off, and sometimes I would be at his door and hear piping voices and pounding footsteps from above, my signal to turn around and go home.

Michael and I were alone one day at his place when there was a knock on the ground floor door and a woman’s voice yelling “Michael?” Panic shot through Michael’s face; he gestured me toward the bathroom, pushed me inside and shut the door before I realized what was happening. It was his ex-wife making a surprise visit in hopes of finding him with cash in hand. Those Art Nouveau apartments, all curves and rounded corners, carried sound beautifully; sitting on the tile floor I could hear every word she shrieked:

“A Playboy model? Really? I hope you know better than to have her around our sons.” Oh boy, I thought. What the other models had warned about posing for Playboy was true. I could get Rabin and Abbas to sit down over hummus and pita and the newspaper headline would read “Playboy Model Wins Nobel Peace Prize.”

Michael spent thirty seconds defending me before emptying his pockets and easing his ex-wife out the door. He released me from the bathroom, wearing such a miserable, guilt-ridden face I had to kiss it and make it all better. Michael’s German-Russian heritage meant that he did guilt as intensely as he did romance, and he had just locked the woman he claimed to love in the bathroom.

I hugged that big-nosed, balding man, knocking his geeky horn-rimmed glasses askew, and the magic cloak of love settled around me, a feeling identical to, yet complete different from, the one sparked by a tender, tenuous kiss with my first Michael, seven years before.

I tried to say, “I love you.” I could not speak the words; it felt like my giddy heart was swelling all the way up my throat. I had fallen for Michael: he was only slightly crazy, and so talented and funny that I was able to overlook the baggage of his two small children and had almost stopped noticing that he was not good-looking.