How Hiroshima Changed the Way We Think about War

Seventy-two years ago, America dropped the first atomic bomb ever used in war. Many Americans were happy to hear the news that a bomb had destroyed the Japanese city of Hiroshima. They were elated at the prospect of an imminent end to the war. And for some, there was satisfaction that the bomb, which had instantly killed over 50,000 Japanese, was fitting vengeance for the attack on Pearl Harbor.

But in the months that followed, the enormity of the bomb’s deadly force began to sink in. Americans grew concerned that a weapon could hold such devastating power.

Only America possessed an atomic bomb at the time, but many assumed it would only be a matter of time before other nations developed their own atomic program. (In fact, the Soviet Union announced its own atomic bomb three years later.)

The concerns grew as the death toll in Hiroshima continued to climb. By year’s end, it had reached 140,000 as people succumbed to the effects of burns, radiation, and other illnesses. In Nagasaki, which had been bombed three days after Hiroshima, the number killed reached 70,000.

It was plain to see that war had been changed.

The Army’s General Staff College conducted an in-depth study of just how the bomb had altered America’s defense strategy. Now, countries that went to war with atomic weapons would face a stalemate neither would want to break. An atomic war was unwinnable and, perhaps, unwageable.

The Army concluded that America’s primary defense in the future would not be military force but diplomatic pressure: negotiations, sanctions, embargoes, compromises. And since diplomacy works best when supported by other countries, America would have to be involved in international politics to support its alliances and control the use of atomic weapons.

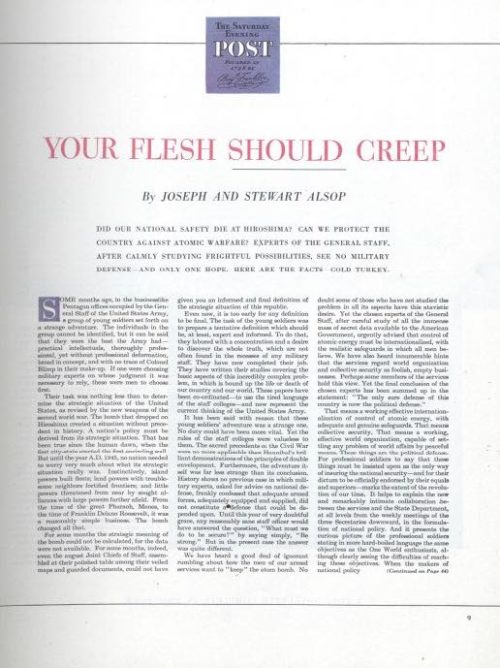

The alternative, a purely military defense in the atomic age, would require vast alterations in the country, according to Joseph and Stewart Alsop. In their July 13, 1946 Post article, “Your Flesh Should Creep,” they described how a military approach to waging atomic warfare would affect America.

- Cities would have to be redeveloped to reduce concentrations of population and industry. Great citieswouldbecome ghost towns.

- Americans — men and women — would be “trained in group action, in group discipline and in the disaster-control procedures required in time of great emergency. Each citizen will learn his doomsday duties.”

- A specially trained, unelected, emergency government would be keptwithin a cave ready to take over the administration of the country.

Some aspects of a military approach to waging atomic warfare were adopted, however, even though the Alsops would have thought them unfeasible.

For example, they scoffed at the military notion of building an immense, invulnerable mechanism of retaliation — a chain of rocket installations, across the nation, buried deep underground, operating on 24-hour-a-day alert.

“No true democracy,” they wrote, “can maintain an immense and powerful armament in a state of 24-hour alert for years and decades on end.”

Moreover, such a system would require one person with the ultimate responsibility to launch Armageddon on the enemy. “No true democracy can confide to a single individual, the rocket controller, such responsibility as would be his,” they added.

Yet over 1,000 Minuteman missiles were stored in underground silos in the 1960s, and Atlas Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles were kept in silos on six Air Force bases. And — despite deep misgivings — there is, indeed, one person with the responsibility of launching our nuclear arsenal: the president.

Featured image: Wrecked framework of the Museum of Science and Industry in Hiroshima, Japan. (Shutterstock)

From our Archives: How You Can Survive an A-Bomb Blast

The best-selling book No Place to Hide was David Bradley’s eyewitness account of the weapons tests at Bikini Atoll. Richard Gerstell was also part of that military testing crew. But unlike Bradley, he wrote this article to reassure Americans in 1950 that if under nuclear attack “there most definitely is some place to hide.”

This article was recently mentioned in Alex Boese’s new novel Electrified Sheep, a collection of curious science experiments. In the book, Boese references Gerstell’s inclusion of the psychoneurotic goats filmed on one of the naval vessels during the weapons testing at Bikini.

How You Can Survive an A-Bomb Blast

By Richard Gerstell

If you think a falling A-bomb means the end of everything, this remarkable report may change your mind. Here are protective measures you can take—and proof that the blast is not always so fatal and frightful as you think.

After service in the wartime Navy and postwar work in boarding radioactively “hot” ships in the Bikini tests, I received a call from the Department of Defense to help draw up plans for protection of the civilian population against possible atomic attack. As far as we knew, Russia at that time did not have the bomb, but we were taking no chances. When I went to Washington to report for duty, I felt pretty sure that atomic destruction for a sizable portion of the human race was inevitable. Many others who, like myself, had got a worm’s-eye view of the Bikini shambles felt the same way. The title of a book which grew out of this close-up viewpoint summed up our gloom well. It was called No Place to Hide.

Today, after having gone over the full and integrated reports of the Bikini tests as well as preliminary reports from the later tests of newer bombs at Eniwetok, and thus having obtained a comprehensive over-all picture, I have frankly changed my mind. I have concluded—and I honestly believe—that although the atomic bomb does indeed come up to its billing as the most destructive weapon devised by man, it definitely does not mean the liquidation of mankind. You would, for instance, have a difficult time trying to convince a citizen of Tokyo that he suffered less than did the inhabitants of Hiroshima and Nagasaki; for although 66,000 died in Hiroshima and 39,000 in Nagasaki, no fewer than 84,000 perished in the fire-bomb raid on Tokyo in March, 1945. Truthfully, I would as soon be in an atomic raid as in a saturation blockbuster or incendiary bombing.

Actually in major respects the atomic bomb is similar in effect to conventional bombs, and, just as there are common-sense precautions to be taken against the ordinary bomb, so are there practical safety measures to be taken against the nuclear weapon. And these all of us may very well commit to memory. To paraphrase in reverse that horrendous book title, there most definitely is some place to hide.

It has been estimated that in the event of attack upon this country, thirty minutes’ warning, even with radar defenses, is often the most that can be expected. Yet thirty minutes, or even a fraction of that, can be a long-enough time in which to take those measures that will reduce to a minimum the human injuries caused by the atomic bomb.

Basically, the only difference between the atomic bomb and the conventional explosive bomb lies in the nuclear weapon’s radioactivity, which is much less of a wartime threat than most people believe. The atomic bomb’s most destructive elements are its blast and heat, which—although of far greater magnitude—are the same forces as in the ordinary bomb, and what is a defense against the blast and heat of one is a defense against the same two forces of the other.

An atomic explosion is sometimes an eccentric thing. In Nagasaki, for example, crude timber shelters covered with four feet of ordinary earth remained standing 100 yards from ground zero, the surface point directly beneath the detonation, while tile roofs were blown off buildings four miles away. The blast may bounce ineffectively off one wall and ricochet across a street to demolish another. Yet, in general the explosion follows certain predictable patterns of behavior.

It is known, for example, that relatively few direct injuries are caused by the blast or the actual “squeezing” of the bomb’s pressure wave. Most injuries and fatalities are results of the blast’s indirect effects—from being thrown against something or struck by a falling object. Therefore, in terms of individual protection, a person with only a few seconds’ warning would lessen his chances of injury by lying flat on his stomach, face in his arms, eyes closed tightly. Instead of looking up immediately, he should remain in that position for eight or ten seconds after the detonation. This would be not only a protection against such things as flying glass but also against the temporary five minutes or so of blindness that could result from looking into the explosion’s dazzling burst of light.

If one were outside at the time of a raid, this prone position should be taken in a ditch or gutter or against the base of some substantial structure—not a flimsy affair that might possibly fall on him. Inside a building, the best shelter would be the basement, and there a person should lie next to a wall, away from the windows, or against the base of some strong supporting column; definitely not in the middle of the floor where the danger of falling beams is much greater. Although there is always a risk of being trapped in the basement, the upper floors hold the greatest hazards; for those floors—aside from being open to the radiological dangers which I will mention later—might collapse.

Except very near the point of detonation, flash burns—the second greatest cause of injury and death—can usually be avoided by the flimsiest of shielding. The ditch, gutter or wall that affords the best protection against the bomb’s blast would act even as a more effective barrier against its heat. Thin cotton cloth might do the trick also. In Japan it was noted that many people suffered flower-shaped burns. It was learned that this was caused by the designs on their blouses, the lightly colored material reflecting the heat rays, the darker patterns absorbing and letting them through. In the event of an emergency, a person should always wear long trousers or slacks and loose-fitting light-colored blouses with full-length sleeves buttoned at the wrist. A hat, brim down, could help prevent many a face burn. Women should never go bare-legged.