How Hiroshima Changed the Way We Think about War

Seventy-two years ago, America dropped the first atomic bomb ever used in war. Many Americans were happy to hear the news that a bomb had destroyed the Japanese city of Hiroshima. They were elated at the prospect of an imminent end to the war. And for some, there was satisfaction that the bomb, which had instantly killed over 50,000 Japanese, was fitting vengeance for the attack on Pearl Harbor.

But in the months that followed, the enormity of the bomb’s deadly force began to sink in. Americans grew concerned that a weapon could hold such devastating power.

Only America possessed an atomic bomb at the time, but many assumed it would only be a matter of time before other nations developed their own atomic program. (In fact, the Soviet Union announced its own atomic bomb three years later.)

The concerns grew as the death toll in Hiroshima continued to climb. By year’s end, it had reached 140,000 as people succumbed to the effects of burns, radiation, and other illnesses. In Nagasaki, which had been bombed three days after Hiroshima, the number killed reached 70,000.

It was plain to see that war had been changed.

The Army’s General Staff College conducted an in-depth study of just how the bomb had altered America’s defense strategy. Now, countries that went to war with atomic weapons would face a stalemate neither would want to break. An atomic war was unwinnable and, perhaps, unwageable.

The Army concluded that America’s primary defense in the future would not be military force but diplomatic pressure: negotiations, sanctions, embargoes, compromises. And since diplomacy works best when supported by other countries, America would have to be involved in international politics to support its alliances and control the use of atomic weapons.

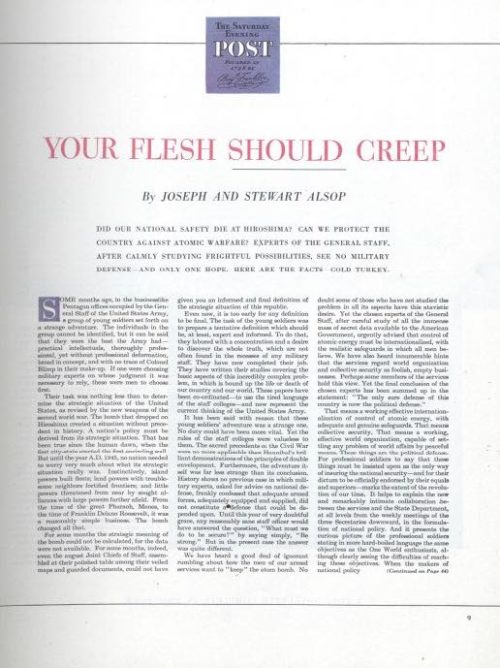

The alternative, a purely military defense in the atomic age, would require vast alterations in the country, according to Joseph and Stewart Alsop. In their July 13, 1946 Post article, “Your Flesh Should Creep,” they described how a military approach to waging atomic warfare would affect America.

- Cities would have to be redeveloped to reduce concentrations of population and industry. Great citieswouldbecome ghost towns.

- Americans — men and women — would be “trained in group action, in group discipline and in the disaster-control procedures required in time of great emergency. Each citizen will learn his doomsday duties.”

- A specially trained, unelected, emergency government would be keptwithin a cave ready to take over the administration of the country.

Some aspects of a military approach to waging atomic warfare were adopted, however, even though the Alsops would have thought them unfeasible.

For example, they scoffed at the military notion of building an immense, invulnerable mechanism of retaliation — a chain of rocket installations, across the nation, buried deep underground, operating on 24-hour-a-day alert.

“No true democracy,” they wrote, “can maintain an immense and powerful armament in a state of 24-hour alert for years and decades on end.”

Moreover, such a system would require one person with the ultimate responsibility to launch Armageddon on the enemy. “No true democracy can confide to a single individual, the rocket controller, such responsibility as would be his,” they added.

Yet over 1,000 Minuteman missiles were stored in underground silos in the 1960s, and Atlas Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles were kept in silos on six Air Force bases. And — despite deep misgivings — there is, indeed, one person with the responsibility of launching our nuclear arsenal: the president.

Featured image: Wrecked framework of the Museum of Science and Industry in Hiroshima, Japan. (Shutterstock)