North Country Girl: Chapter 3 — The Charms of South Dakota

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

While we spent every Sunday in with my dad’s parents, we saw my mother’s parents in Aberdeen once a year, over a long summer visit. We traveled by train, my sister and I in matching navy blue coats and white gloves, first south to Minneapolis and then switching train stations, onto another train heading west. We arrived in Aberdeen in the middle of the night; my grandpa Bill would meet the train and carry us sleeping girls to his car. When I woke up the next morning and saw the faded rose trellis wallpaper I knew I was up in the tower room of my grandparents’ Victorian house. My grandmother Nana loved babies, cats, and wallpaper: the dining room featured huge tropical leaves, like a Rousseau painting and a small downstairs bedroom had a meticulously detailed Old West landscape that encouraged daydreaming about cowboys and Indians.

Nana had a large garden plot across the street, where she grew vegetables; her huge side yard was dedicated to flowers, my Uncle Dale’s white box beehives, and my Uncle David’s pigeon coop. I was a bit frightened of those beady-eyed birds and my mother thought the pigeons were filthy and disgusting and forbid me to go near the coop, one rule that I happily obeyed.

Uncle David, a weird old bachelor, who had once been a noted small town athlete (too oddball for team sports, he was a champion ice skater, runner, and singles tennis player), lived with my grandparents. My Uncle Dale and Aunt Joan lived across the street, and produced a baby a year, to my grandmother’s delight; she adored lap babies, happy to spend hours rocking them and soothing them with an almost tuneless lullaby. I’m sure all of us cousins are disturbed by early memories of being ousted from that warm and cozy nest in favor of a smaller and cuter kid. Eventually even the youngest grandchild got dumped out of Nana’s lap, to be replaced by a cat.

Those visits to Aberdeen were my first chance to really wander and explore outside the confines of a yard, by myself or with a cousin or two trailing behind. Kids were let out of the house after breakfast, expected home at noon for “dinner,” eaten with my grandpa and uncles and any workers from their house painting business who happened to be around; and then sent off again to play until dark.

Aberdeen was a flat plains town, with a looming water tower that was visible from everywhere and marked the way back home. Unlike Duluth, a city that was all up and down hill, Aberdeen was perfect for bike riding. It was a lot hotter than Duluth and no one cared if we cousins turned the hose on each other, creating mud pits on the lawn. There was also that height of civilization, a municipal pool, just down the street, entry 50 cents. (Duluth, proud of its lakeside status and crisscrossed with rivers and creeks, scorned pools.) A short bike ride away was a playground whose main attractions were a snack bar and a rusty, creaky merry-go-round; we older cousins forced the littler ones to push us while we lay on our backs, heads hanging off the sides to better swirl our brains, until one of us was flung off or a pusher lost her grip and went tumbling under the spinning metal wheel. We had gravel from falls embedded in our knees all summer long. I was given a dime to spend at the snack bar there, where I was always torn with indecision.

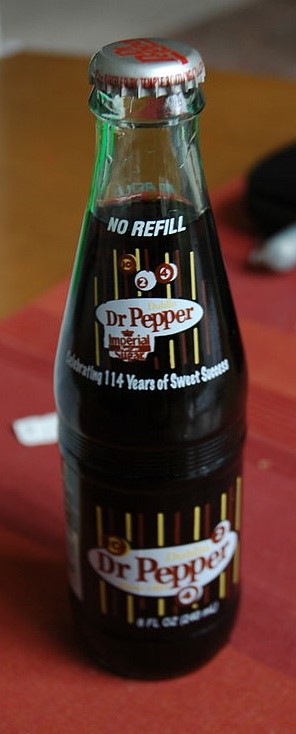

Should I get a Dr. Pepper or a pink Creamsicle (vanilla ice cream coated with raspberry sherbet)? Neither was available in Duluth, though sometimes I could find a misshapen and ice-encrusted orange Creamsicle at the bottom of a store’s ice cream freezer. The Dr. Pepper, icy cold and mysteriously delicious, came with a challenge: I had to lean into that coffin-like cooler, holding the lid up with one hand, the other navigating the bottle through a metal maze until it was finally freed at the end, without smashing my fingers. I would have to drink the entire thing right there, as the empties had to be deposited in a wire rack next to the cooler. An already melting Creamsicle I could take with me, some of the pink and white mess dropping off to sizzle on the sidewalk, some creating a sticky mess on my rubber bike handle grips.

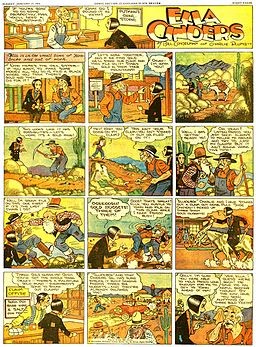

Nana kept her hair eggplant red, and wore her rouge high on her cheeks like a kewpie doll. She had to start every morning with dry toast and coffee lightened with evaporated milk. She had grown up next to her father’s cheese factory in Wisconsin inhaling the fumes from solidifying milk, and the scent of most dairy products made her sick. She was happiest hoeing in her garden or rocking a baby or collecting a new cat; the best-smelling stews on the stove were reserved “for my kitties.” My grandpa Spellman was a kind quiet man, a dead ringer for Cab Calloway, and the only adult I knew who read the funnies in the newspaper; I would hop in bed with him on Sunday mornings so we could page through the colored comics section together, admiring all of them: Ella Cinders, Steve Canyon, Beetle Bailey, Dagwood, Dondi, even Mary Worth, a soap opera in pictures.

Aberdeen had a very minor league baseball stadium, where no one in my family ever went, and a downtown lined with two-story, red brick, glass-fronted shops. On Saturday nights, we brought blankets to the park, where the adults sat around the band shell, listening to the town brass band, out of tune but spiffy in their dark blue uniforms, while the kids ran amok. Afterwards we went to Lacey’s Dairy for ice cream; I always got a cone of White House, vanilla with candied cherries and walnuts.

Another Aberdeen-only treat was my Uncle Dale’s homemade root beer, sweetened with honey from his hives. He brewed up a dark mixture with squares of root beer flavoring, yeast, tap water, and honey, poured it into glass pop bottles saved throughout the year, sealed them shut with a fascinating bottle cap press, and stored them in his basement to ferment. We kids were always warned not to open the bottles until Uncle Dale said. I could never wait that long—certainly the root beer had to be ready by now!—and at least once a summer I snuck down to the basement with a bottle opener, took a mouthful of warm, sweet, flat liquid, poured the rest down the sink, and sneakily hid the empty bottle.