North Country Girl: Chapter 21 — Youth in Revolt

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

The day after I saw The Who, I took the bus downtown to Musicland and bought my first record, The Who Sell Out; the album cover was a photo of Roger Daltrey bathing in Heinz Baked Beans. My mother shook her head at what she saw as a waste of $2.99. “You can listen to that music on the radio for free.” That was my cue, Youth in Revolt, to go back to Musicland and buy the new Rolling Stones album, Between the Buttons. I spent hours in my room listening to these two records, song after song, till the needle hit the sizzling rain drop song that indicated the end of that side, then flipping the record over, searching for clues to that other world like a radio astronomer listening for signs of life from distant stars.

I had no one who shared my new obsessions: rock and roll, drugs, sit-ins, protest marches, love-ins, be-ins, boys with long hair and romantic lacy shirts. Wendy’s mom’s two-year gig as dorm mother was up and they moved back to International Falls before the start of school. We promised to stay in touch, but phone calls would have been the dreaded Long Distance, so frowned on by my dad that my mom limited her calls to Aberdeen to two a year, one at Christmas and the other to let them know when we would be arriving for our summer visit. Wendy and I wrote, but letters didn’t capture the immediacy and high drama of the day-to-day junior high experience.

Despite my best friend’s departure, I wasn’t quite as lonely as a cloud when ninth grade started. I had a few girlfriends I sat with at lunch: Kathy O’Dell, Karen Ringwald, and Cindy Moreland, another newcomer to Duluth who had been taken in by our little group. But where were my fellow Youths in Revolt? Where were the readers of John Barth and John Updike, the fans of op art and experimental theatre, the anti-war protesters? Most importantly, where were kids who could get drugs? They were not at Woodland.

Kathy was a dreamy poet and painter, with long, blonde Michelle Phillips hair and perfect skin. She was waiting to be teleported to a garret in Paris, a black beret magically appearing on her head. Karen and I shared a reputation, guaranteed to impress no one, as the smartest girls in ninth grade, Karen slightly edging me out in math and routing me in Spanish. She was a 14-year-old cynic, dismissive of popular opinion, who regarded ninth grade boys as lower life forms. She vanished the next year, supposedly to some boarding school for super-smarties; this would have been the fodder of pregnancy rumors if it were any other girl besides Karen who disappeared.

Cindy Moreland was cute, perky, and as boy-crazy as I was, so the two of us eventually gravitated towards each other. We were far from soulmates; if I went to her house I had to listen to Gary Puckett’s “Young Girl” and “Girl You’ll be a Woman Soon” on repeat while we went through a box of Bugles and bottles of Coke and fretted over how to get boys to like us. At my house, I forced her to listen to The Who and The Rolling Stones, while we guzzled ginger ale (which was supposed to be for cocktails, not kids) and continued the discussion.

My mother, who generally ignored all kid goings-on, overheard us bemoaning our lack of success with boys. She was a former beauty queen, rising from Miss Aberdeen S.D. to Miss Upper Midwest, who had boyfriends coming out of her ears. Her advice was, along with always wearing cute clothes, to go up to a boy we like, say “Hi!” and start a conversation. This was the equivalent in my mind of suggesting I climb Everest.

Cindy was an optimist. Her taste ran strictly to jocks and she had a plan to reel one in: cheerleading. Football players and cheerleaders were as natural a combination as peanut butter and jelly. No actual gymnastic ability was required to be a Woodland Junior High cheerleader: all you had to do for the eight or so home games was yell and shake your pom poms. Since there is no justice in junior high, cute, peppy Cindy Moreland did not make the cheerleading squad; only the already gilded popular girls were chosen. Cindy was heartbroken and spent the rest of the year practicing splits and hand springs, determined to win a spot next fall on the East High School cheerleading squad.

The very idea of cheerleading made me want to puke, but I had enough Minnesota nice left that I did not make fun of Cindy’s goal. My own aspirations to become a war-protesting, civil-rights-marching, free-love-practicing pot smoker were much more ridiculous.

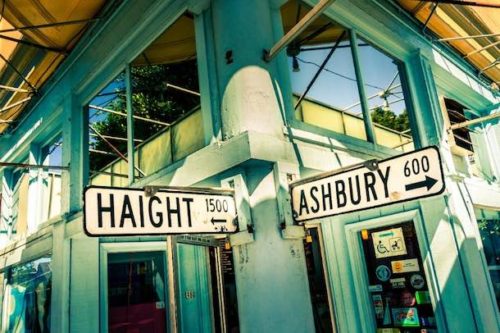

I devoured every bit of information on the counter culture that I could get my hands on. My sources were laughable. I pored over The Saturday Evening Post’s coverage of Haight-Ashbury and tried to figure out how to get there on the twenty-eight dollars I had in the Pioneer National bank.

Time magazine covered the anti-war protests, but with a maiden aunt’s tut tut of disapproval. But in the back pages of Time I found a tiny ad for a new magazine, Avant Garde, which promised to cover every subject needed by Youth in Revolt. I snipped out the ad, filled in my name and address and begged my mom for a five-dollar bill (special introductory price), and handed the envelope off to our mailman. A few months later, after I had forgotten all about it, I received a plain brown wrapper that enclosed a fat, glossy magazine. Avant Garde was all I desired and more: anti-war articles! Photos of stoned, unwashed hippies in squalid New York City apartments! Drawings from the Kama Sutra (what the hell were they doing?)! A whole article on the f-word, which I had never seen in print before! I had found my peephole into the 60s.

Unfortunately, the editors of Avant Garde must have believed that printing schedules were for squares, man; months would go by between issues. Even more unfortunately, my dad came across an issue I had thoughtlessly left on the living room couch. He had to look at only a few pages to know that his eldest daughter was in danger of being ruined by a magazine and thundered into my room, shaking the offending publication, and roaring that whoever wrote crap like this deserved to be horsewhipped. I was careful to hide all my issues after that.

Most unfortunate of all, Avant Garde kept taking my money, but stopped sending magazines. I sadly replaced it with the leftie Saturday Review, a magazine with all of the pretention of Avant Garde but with none of the panache.

***

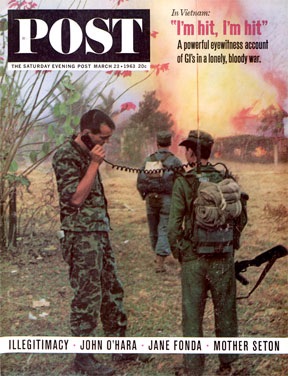

Stuck up in Duluth, I could only glimpse the revolution I knew was going on, a revolution I desperately wanted to be a part of but had no idea how to join. No one in Duluth marched against the Vietnam War.

The war was something on the TV news, or below the fold on the front page of the Duluth Tribune. I announced myself as anti-war at every opportunity, even though everyone I knew at that point, kids included, believed in the domino theory, that we needed to stop communism in Southeast Asia or we’d all be wearing Mao suits. My own parents didn’t give two sh*ts about the war; the biggest response I could get out of them when I spouted my revolutionary rhetoric was the eye roll. They did forbid me from letting slip any of my wacky new-found opinions in front of my commie-hating grandpa Haubner, lest I give the old man a heart attack.

Civil rights were also a non-starter in almost all-white Duluth. The only black person I had seen in Duluth in my ten years of living there was the elevator operator at Oreck’s department store. When she was five, my sister Lani had stared at the slight, well-dressed woman perched on her stool for a full minute before announcing “I don’t like your black face.” The elevator operator snapped back, “And I don’t like your little white face,” and my mother hustled us out of the elevator and we took the stairs up to Better Dresses.

I got my first chance to stick it to the man thanks to the Woodland Junior High dress code, which stipulated that girls’ skirts must be knee-length. It was the height of the miniskirt craze, and my mother, the slave to fashion, made sure that all my skirts for ninth grade were stylishly short.

My revolt would have sputtered out if it hadn’t been for my English teacher, Mr. Koch. No one else at Woodland cared about the length of the skirt worn by a boring, nerdy honor student with stumpy legs. The dress code ruled that when you got down on your knees, the hem of the skirt had to touch the floor. (No one acknowledged how demeaning it was to have to kneel down in public on the grubby linoleum school floor.)

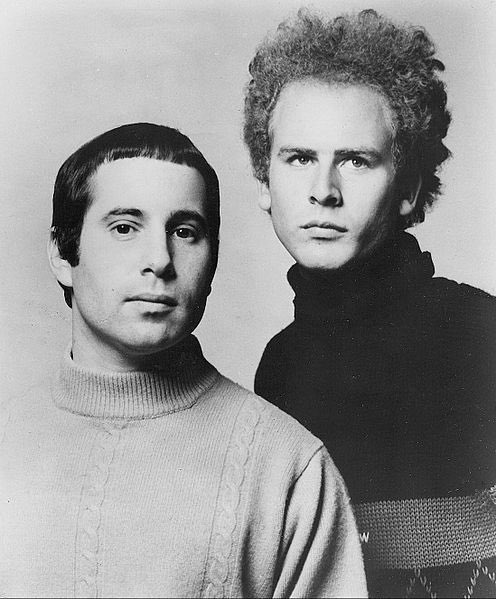

Mr. Koch, short and stubby, had turned his small black eyes on me from the beginning of the year. He wore a peevish look whenever I started in on my anti-war rhetoric. He grumbled when I chose the lyrics to Simon and Garfunkel’s “I am a Rock” for my poetry paper, threatened to make me redo it, and then awarded me a grudging B-.

Showing up in a shiny red pleather miniskirt was a serious transgression. Mr. Koch ordered me up to the front of the room, made me kneel, eyeballed the few inches between skirt and floor, inches occupied by my bony kneecaps, and sent me to the principal’s office. When the bored school secretary reached my mother and told her she needed to bring me a change of clothes, mom said the hell with that and that they better send me back to class or else. After all, she herself had plucked the skirt from the sales rack in Dayton’s Junior Miss department.

I had single-handedly put an end to the Woodland Dress Code. When I returned triumphant to Mr. Koch’s room, my classmates lined up to sign my pleather skirt in indelible black or blue Bic pen. My mother, horrified that I would ruin my clothes like that, threw it out.

My first successful act of rebellion put me directly in Mr. Koch’s sights. I pulled the trigger myself when during a class discussion I piped up to say that I couldn’t wait to try LSD, which sent Mr. Koch into a red-faced paroxysm. When he could speak again, it was to give me a series of mandatory extra assignments. Assignments that for some reason had to be completed in his apartment over several Saturdays. This situation was made even creepier by the flitting about of Mr. Koch’s all too cheerful wife, while I read Romeo and Juliet aloud at their kitchen table and Mr. Koch stared at me.