Miracle Seeker

I was not raised Catholic. I can’t recite the Holy Rosary. And I certainly don’t have what it takes to be considered a devout anything—unless knowing the dialogue to all six seasons of Sex and the City counts for something. But I’m not exactly an atheist either. I’ve always felt a strong sense of devotion to a higher entity. Yet at a dinner party recently when I spoke excitedly about my upcoming trip to Lourdes, the holy shrine in the South of France, I was quickly cut short.

“But you’re not religious,” said a female acquaintance. Her remark spilled across the tablecloth like a tipped-over glass of red wine.

“I used to go to church every Sunday,” I said, somewhat defensively. “And I went to Christian youth camp one summer.”

I went on to explain that Lourdes gets more than six million visitors each year, and I highly doubted every single person who visited the famous grotto of Massabielle was a staunch Catholic.

But who was I trying to convince, her or me?

True, her verbal stoning made me momentarily doubt my bonafides as a miracle seeker. But though not a devout Catholic, I had a good reason for the pilgrimage; being diagnosed with malignant melanoma at age 50 was reason enough. My cancer is what clinicians call Stage IIIB. Look it up. Words like “prognosis somewhat poor” and “very little chance” leap off the screen. Still, my decision to make the trek had been built on monumental hope. For months I had been imagining myself there, miraculously saved. In the end, I took this woman’s ugly remark as one of the many disconcerting side effects of having cancer and handled it the way I do with doctors’ sad faces and negative statistics—I ignored it.

I am running alongside track 19 through the Montparnasse train station toward the silvery vessel that will transport me from Paris to the Pyrenees to the place I’d been dreaming of since I was 15 when I watched the film classic The Song of Bernadette. The thought of standing at the grotto where a young peasant girl, Bernadette Soubirous, saw the Virgin Mary appear 18 times in the year 1858 makes me euphoric.

I have less than two minutes to find the designated rail car stamped on my ticket. It seems a never-ending distance. Traveling too fast, my suitcase tilts on its rickety wheels and falls over.

“S***!” I scream. As I collect my bloated baggage sprawled across the pavement, a nun crosses my path. Uh oh, I think. She’ll probably send up word on high that there’s a foul-mouthed American woman on the way. That won’t bode well for my chances for the “miracle” list. Boarding the train, I notice a sickly bald lady who looks as though she’s undergone intense chemotherapy treatments. Near her is an extremely frail teen boy in a wheelchair reading a French translation of The Hunger Games. Both of these angelic souls seem more worthy of a miracle than I. I’m certain neither of them has ever cussed in front of a nun.

Looking at me, you’d never know my plight. People say I look “fantastic” six months after undergoing two major surgeries. The first excised the tumor on my upper left arm and removed two sentinel lymph nodes to determine if the cancer had spread. The cancerous culprits indeed had set up camp in the first node. And my physician, the world-renowned Donald L. Morton of the John Wayne Cancer Institute in Santa Monica, California, next recommended removal of my axillary lymph nodes (which form a sort of chain from the underarm to the collarbone) despite the painful side effects such as permanent nerve damage and the potential threat of lymphedema, or swelling.

“You don’t have to have chemo?” some people question. “No radiation?”

“Nope.”

“Wow, that’s great,” they say.

I guess that the thought that I won’t lose my long, blonde locks and shrink down to a skeletal frame or puke uncontrollably while sporting a headscarf is an upside. The downside is that there is no treatment or cure for this stage of melanoma—only more cutting should a new cancer emerge. My job is to be vigilant should I note anything suspicious, then to hightail it into the office for further study. This is, quite frankly, terrifying. No neon sign points to the location of a fresh melanoma. My doctor says that the next one will most likely not sprout directly on my skin, but just under it, so I’m supposed to gently rub my (numb) five-inch scar where the first growth emerged, feeling for a new invasion.

The chance of recurrence is quite high. In fact, when you’re Stage IIIB, it’s not a matter of if, but when. So every six months I undergo PET scans or chest X-rays to detect if the cancer has progressed to the dreaded Stage IV. I call it the “mean test.”

They tell me my five-year survival chances are 60 percent.

Melanoma—a cancer of the skin primarily caused by sunlight —is often confused with curable basal cell and squamous-cell skin cancers. But melanoma is the eighth most common malignancy in the U.S., and its frequency is rising faster than any other human cancer. In the 1930s the survival rate for this disease was extremely low; now 5- and 10-year survival rates of Stage I melanoma are well over 80 percent on average. But there are different forms, stages, and classifications that each have different prognoses.

I have nodular type, which is the most aggressive. Even when I discovered an abnormally large mole that quadrupled in size in less than three months, both the nurse and a dermatologist I initially visited assured me it was “nothing.” I sensed that they were both wrong and demanded its removal and biopsy. A case like mine—where skin cancers masquerade as something normal—is a perfect example of why people should get checked regularly. Don’t let your best friend, partner, neighbor, or even your family doctor discourage you from seeking expert attention. Had I listened to my healthcare team, I may have left that HMO allowing my already aggressive cancer to flourish, and I would not be writing this today.

Living with cancer is a learning experience. Part of that learning is to avoid the many misconceptions. Everyone knows somebody who has, or has had, cancer. They are quick to offer medical, herbal, even spiritual advice as well as clinical trial information. Truly, I am touched whenever someone offers any hope they feel may erase my diagnosis. But if I hear one more person tell me the story of their Aunt Jean who had skin cancer for four years and now is totally fine, I’ll lose it. (No offense Aunt Jean.) All melanomas are not alike.

“Is this your first time at Lourdes?”

I look up at a frail-looking pilgrim just beside me in the line for the sacred grotto.

“Yes,” I say.

The woman’s name is Selam. She has come from Vancouver, Canada, but originally hails from Ethiopia. She is 40 years old. Within seconds we are swapping war stories.

“Melanoma, Stage III,” I say.

“Colon cancer … I’ve been given six months to live,” she whispers.

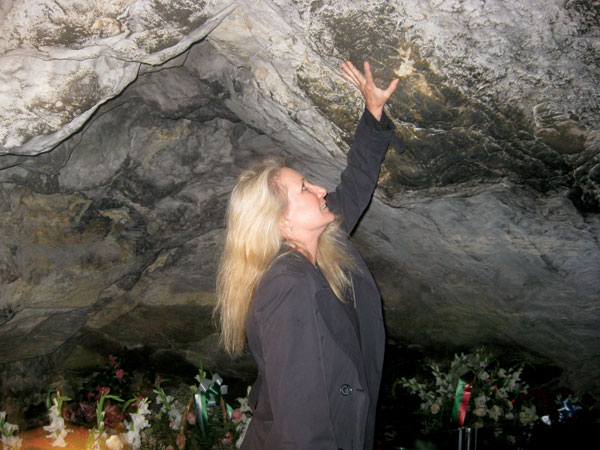

I let her step in front of me and study how she grazes the grayish stone that leads to the niche with her left hand, stopping every few feet to kiss the rock. A white rosary entwined in her right hand swings gently from side to side.

I begin to copy her every move. If she makes the sign of the cross, I do, too. If she pats the water droplets that trickle from the cave-like surface and touches her face, I do the same. It is as if she’s been sent to me as a personal guide. Nearing the sacred spot, she begins to weep. I stroke her back the way a mother would soothe a child with a skinned knee.

She kneels before the statue of Mary resting high in an alcove. Dabbing moisture from the stone, my hand presses the gash on my upper left arm, but I forget to ask Mary for anything because of a deep concern for my new companion. Selam’s despairing sobs grow louder—agonizing wails echoing in an already hushed enclave.

Minutes later, she rises and turns toward me.

I open my arms wide and she collapses against me. We hold each other in a long embrace as though lifelong friends.

“I want you to have this,” I say, reaching into my bag for a vintage religious medal of Bernadette that a dear friend sent with me for luck. “Pin it over your heart. It will protect you.”

“Oh, thank you, my love,” she says. “I prayed I would meet someone here.”

Who knew my presence alone would answer a dying woman’s prayers? Fear of what I lacked spiritually had been eating away at me in the days leading up to this moment. But her words are like a salve.

As the two of us walk arm in arm, we sing aloud, butchering the lyrics to “Ave Maria,” giggling in between verses. We pass thousands of invalids, some on gurneys and many in wheelchairs, most assisted by unpaid hospitallers—volunteers who look like a combination of nun and nurse. I have a sudden, unexpected calling to be one of them.

Selam tries to disguise the immense pain she is suffering and insists on our sitting together for hours at a sidewalk cafe, wiling away the afternoon sharing our hopes, fears, and her desire to find one last love. As we sit and talk, any need to justify the depth of my religious belief seems to vanish.

I had arrived alone at the holy shrine, a restless soul beside those green fields, and rather than glimpse the image of the Virgin Mary I had my own singular and singularly valuable divine visitation. Melanoma had brought me to Lourdes and given me Selam, the woman whose name means “peace.”

Three days later, fighting back tears and promising we’d meet again, she gives me a final gift: a pocket Holy Rosary booklet complete with tiny red beads and crucifix.

“See? Now you never need worry,” she says sweetly. “You’ll always have the right words.”

Six months later, after a chest X-ray, I am classified as disease-free. I harbor much hope, but there is always my next scan. Upon returning from Europe, I would speak with Selam twice. Her cancer had rapidly spread, and she was bravely undergoing extreme bouts of experimental chemotherapy. Her last words to me were, “I’ll call you next week, my love.” That was several months ago.

Just recently I have signed up with Our Lady of Lourdes Hospitality North American Volunteers to become one of the thousands of companion caregivers that Selam and I had seen. Some of the pilgrims will understand English, and some will not. Yet I’m not too concerned about the language barrier. Selam showed me that faith does not require proficient verbal skills.

If she were here with me now I’d say, “Can you imagine? Me? Speaking French? Might as well be Swahili!”

She’d just smile and make the sign of the cross.