The Healing Power of Baseball in Japan

Cozy spring breeze

Over the grassy ground

How I want to play ball!

—Shiki Masaoka (1897)

Day 1: Tokyo

At the start of the Japanese baseball season this past spring, the breeze over the grassy ground at Tokyo’s historic Meiji Jingu stadium was not cozy. It was a brisk, moist wind that swept over the diamond and crashed into the stands. Fans rubbed their arms with gloved hands. Even so, it was time to play ball, and nothing was going to dampen their spirits. It was the opening series between the Tokyo rivals, the host Yakult Swallows and the visiting Yomiuri Giants.

In Japan, baseball is the national sport, but even that description doesn’t quite capture the intensity, emotion, and enjoyment the Japanese attach to its rituals. I travel not to see sights but to see what the people who live where I go really care about, and that’s what I was looking for when I set out on a short journey across Japan. In Tokyo, I had met up with Katsura Yamamoto and Nao Nomura, friends of friends from home, who were helping get me started.

Built in 1926, Meiji Jingu is a cherished venue like Wrigley Field or Fenway Park. The Swallows’ faithful wore the team’s alternative home jersey, a Day-Glo lime green that made the stands appear as if they’d been streaked with highlighter. Fan club captains, looking like martial artists in happi coats and black headscarves, shouted cheers through bullhorns. Fans serenaded players, such as the Swallows’ superstar second baseman, Tetsuto Yamada: Ya-ma-da! Ya-ma-da, Yamada Tetsuto! Ya-ma-da, Yamada Tetsutooooo! Yamada and the Swallows jumped on the Giants’ pitching early, and the fans stomped, high-fived, banged plastic bats, blew horns, and opened and closed plastic mini-umbrellas as players crossed home plate, a Swallows custom that made all of Meiji Jingu twinkle — except in left field, where Giants fans, wearing their team’s bright orange, sat, still and subdued, at least until the Giants came up to bat, when they raised such a ruckus that you might have thought their team was winning.

I hailed a “beer girl,” as the almost exclusively female purveyors of fresh brew in the stands are known. They run the stadium steps with kegs of Asahi, Sapporo, and Kirin in backpacks for more than three hours, but even more impressive are their indefatigable smiles.

“The pretty ones make more money,” Nao said. “Some of them have been discovered and became models or actresses. If they work for the Giants, they’re on television all the time.”

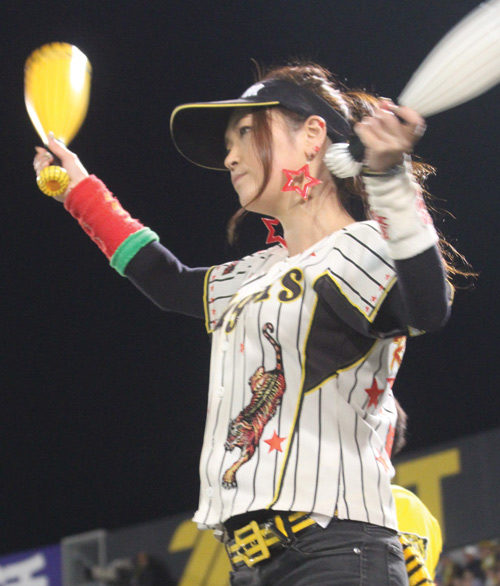

The Giants are Japan’s oldest and most beloved team. They’ve won 30 Japan League championships since the circuit was created in 1936. The Giants are also Japan’s most despised team, and my friends Nao and Katsura, historians in non-baseball life, love to hate them. Nao’s team is the Hiroshima Toyo Carp — her late father was from Hiroshima — while Katsura adores the Hanshin Tigers, the Giants’ archrivals, who play near Osaka. During the game, she frequently checked her phone for Tigers updates. Her love affair with the Tigers had not prevented her from marrying a devotee of the Chunichi Dragons, the team in Nagoya. Their intermarriage produced a son, now 14, who has chosen the Tigers.

“He’s a good boy,” Katsura said with the unmistakable tone of a victor.

Other good boys sat throughout the section. They wore school uniforms and filed down the aisles to their seats with the correctness of parliamentarians shuffling into session. Despite their formal clothes and posture, they were having fun. But they were not just any students on a school trip. They were all survivors of the 2011 earthquake and tsunami that triggered the Fukushima nuclear accident. The Swallows had brought them as special guests, and when they were announced on the P.A. between innings, the entire stadium, including the players, stood and cheered.

There was something quintessentially Japanese about the experience. The baseball stadium is where harmonious, courteous, rule-abiding Japan lets down its hair. Almost from the beginning, when an American missionary named Horace Wilson introduced the sport here in 1872, Japan adopted baseball as its own. As one Japanese writer put it, “If the game hadn’t already been invented in America, it would have been invented in Japan.” But the ballpark here serves other purposes, too: It is a cultural inheritance transmitted through bloodlines, a meeting spot, and, as I would discover soon enough, a place of emotional refuge.

Day 2: Osaka-Koshien

My friend Shutaro Suzuki, a devoted member of the Swallows’ fan club, insisted that I see Osaka’s team, the Hanshin Tigers. “They are the most crazy!” he told me. So I boarded the Shinkansen, aka the bullet train, west to Osaka. The train is state of the art, with airy compartments redolent of leather that offer an ideal vantage from which to watch the landscape of coastlines, forests, and mountains streak past.

The Tigers’ field, Koshien, has special meaning to Japan because it hosts a two-week, 49-team school tournament that, each year since 1915, has crowned a national champion. Tigers fans were certainly colorful, many in black and yellow, with tiger masks, tiger whiskers, tiger socks, and tiger tails. Some had dyed their hair with streaks of yellow. I took my seat in center field. No one around me spoke English, but once they saw I was an ally — as a matter of baseball-travel policy, I always root for the home team — they offered me cold chicken tempura and whiskey highballs, and high-fived and fist-bumped me. When the Tigers chased the opposing BayStars’ pitcher and the fans bid him sayonara with “Auld Lang Syne,” I sang along, even though everyone else was singing in Japanese.

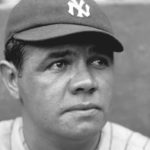

Outside, I found Koshien’s monument to Babe Ruth, a plaque set in a block of stone mounted in a pavilion. Ruth played here while leading a legendary 1934 tour of American all-stars across Japan. It was a spectacular success and critical event in the history of Japanese ball, helping launch the country’s professional league two years later.

“Ruth was very important to Japan,” Robert K. Fitts, author of Banzai Babe Ruth, a superb history of the tour, told me. “He was the most popular athlete in the world. He was like Muhammad Ali. The Japanese considered amateur ball as pure, and professional as tainted. The Ruth tour showed it could be honorable. It also showed the economic potential.”

Japan was good for Ruth, too. His skills were in decline, his career drawing to a close. But in Japan, he magically found his swing, and his youth, again, mashing 13 home runs in 18 games. Crowds lined streets serenading, “Banzai Beibu Rusu!”

Ruth even shared his hosts’ fantasy that the tour would restore deteriorating U.S.-Japan relations. He returned to America full of optimism, his trunks packed with rare Japanese objets d’art. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor seven years later, he opened the windows of his apartment above New York’s Riverside Drive and pitched the Japanese treasures one by one onto the street below.

The disaffection was mutual. For the Japanese, banzai turned into a different kind of rallying cry. Their soldiers in Burma were said to have charged into battle screaming, “To hell with Babe Ruth!”

Day 3: Hiroshima

My next stop was Hiroshima, where the war ended when American bombers silenced those battle cries and really sent this Japanese city to hell. It is, somewhat incongruously, a cheerful place of 1.2 million people. It has wide, busy streets, pedestrian-only districts with fashionable boutiques, artsy cafés and teahouses, good restaurants, a red light district that has become somewhat standard in large Japanese cities, and an expansive public park along the Ota River with striking sculptures and statues recalling that it was here that, on the morning of August 6, 1945, in a hot flash of light, 140,000 lives were extinguished, with tens of thousands more perishing later.

Hiroshima’s team, the Toyo Carp, was off for the week, but I wanted to see the city, which had risen from the ashes, a revival in which baseball played a role. Even after the war, the Japanese never considered abandoning their American sport. On the contrary, they seemed to embrace it even more warmly. In 1946, the Japan Baseball League resumed play and, in 1949, announced an expansion from 8 teams to 12. Hiroshima wanted a squad, but the city was so devastated and impoverished that it couldn’t attract one of the corporate sponsors that typically fund Japanese teams. So its people raised a campaign, collecting public donations, and in 1950 fielded a team on their own. The city named the team for the abundant koi in the Ota River, but chose the English word, carp. Another name that was considered was the Atoms.

I visited the A-Bomb Dome, the former Hiroshima Prefecture Industrial Promotional Hall near ground zero that somehow withstood the blast, before arriving at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. The opening exhibit is a diorama of three figures — a woman, a girl, and a boy — their skin hanging like wax from their bones, an exact depiction of physical torment not even imagined by Dante. All of the exhibits were unspeakably sad, but perhaps none more so than the tricycle beloved by a 3-year-old rider who perished. His father, feeling the boy was too young to be left in the cemetery by himself, had buried him in his backyard with the tricycle. A dozen years later, when the boy’s remains were finally interred in a cemetery, the tricycle was moved to the museum.

“It’s a myth that people were vaporized,” a docent named Kumiko Seino told me matter-of-factly. “They were carbonized. Their bodies were burned black, like hard wood.” During the recovery, the Ota quickly filled with corpses. A lack of equipment made burial difficult; a lack of wood made cremation equally challenging.

Kumiko was one of the museum’s “memory keepers,” who share their experiences as hibakusha — survivors and children of survivors. One reason she began volunteering was that it pained her how often she met young Japanese who knew little about the bombing. “They think the bomb fell in an open park,” she said. “They don’t realize it was filled with people and it’s a park now because they were all destroyed.”

She took me to the Peace Bell and the Children’s Memorial and into the basement of a building where I had to put on a hard hat. A worker had survived here, protected by the concrete despite being only a little over 500 feet from ground zero. In one corner was a senbazuru, 1,000 origami cranes on string. It’s a way of lighting up the space and showing that people remember. Little else seems to have changed. A steel door is still canted on its hinges.

Kumiko walked me around the Peace Park, showing me different cenotaphs — monuments to families that once lived here. “Takada’s wife and children,” said one. “Takagi and his wife,” said another.

“Sometimes I feel I am coming to see my grandmother,” Kumiko told me. “I don’t like to come at night. Maybe there are ghosts.”

“Why ghosts?”

“Because they don’t go to heaven. They died so quickly they didn’t know they were dead.”

I don’t believe in ghosts myself, but in meeting Kumiko and others, it wasn’t hard to see how the living people here could be haunted. Hiroshima is full of people born after the war who were their parents’ second try at life. I encountered no bitterness; on the contrary, Kumiko was careful not to make visitors uncomfortable. What happened happened, there was no going back, and Hiroshima’s mission as a city has become to make sure it never happens anywhere else.

Later, I walked down a side street and slipped into a plain but appealing little restaurant. Two men signaled that a seat next to them at the counter was free. Hironabu and Hiroyuki, both 61, spoke limited English, but between hand gestures, nonverbal cues, and a translation app, we passed an evening of remarkably wide-ranging conversation. I bought them a round of shochu; they reciprocated with a round of chicken meatballs. I got a lesson in restaurant Japanese: Yaki means grill and tori means bird. To help me understand what I might be ordering, they patted body parts. Behind a glass panel, the chef-owner turned skewers over hot coals with the attention of a surgeon performing an organ transplant. Which, in a sense, was what he was doing.

“Kidneys?” I asked. “You have two?”

“No! One!” he said. “Shio kimo.”

I offered other possibilities — heart, stomach, intestines. “Oh, I know,” I said. “Liver!”

“Yes! Liver!”

We ate atsu-age, thick cuts of deep-fried tofu, lotus root, and shiitake mushrooms. “Shiitake!” Hironabu said, and was overjoyed to learn we use the same word in English.

Their parents were survivors. Both men were born in 1955, 10 years after the event. Like Kumiko, they represented the city’s reissue, its rebirth, but neither of them had ever discussed it with his parents. It was just there in the background. There were other things to talk about.

“You play baseball?” Hironabu asked.

Yes, I told him, I played third base in high school.

“He,” Hiroyuki said, pointing to his mate, “center field. Me, I watch.”

“I was no good,” Hironabu confessed.

“Me neither,” I said.

“You know the Carp? They are the number-one team! The best team!”

We drank to that.

On the way back to the hotel, I stepped into a 7-Eleven, which had copy machines that also allow you to order and print baseball tickets. Everything was in Japanese, but it was easy to get a store clerk to help. The next day, I planned to go to Fukuoka, the largest city in Kyushu, the westernmost large island of the Japanese archipelago, to see another game.

Back in my room on the 10th floor of my hotel, I lay on my back and closed my eyes. A little later I felt myself swaying, and for a moment wondered if I’d drunk more than I’d realized. As the bed began to swing like a hammock, I gripped both sides of the mattress and held on until the earthquake passed.

Day 4: Fukuoka

The Fukuoka SoftBank Hawks can play indoors when they need to — the Yahuoku! Dome, completed in 1993, was Japan’s first retractable-roof stadium — so the one thing I hadn’t worried about was being rained out. I couldn’t have anticipated an earthquake. In fact, it was a whole series of earthquakes, dozens of them, foreshocks and aftershocks sandwiching the main event, 7.3 on the Richter scale, that I’d felt all the way back in Hiroshima. Dozens died, at least a thousand were injured, and many tens of thousands found themselves without shelter.

Further spasms buckled highways and bridges. But the trains to Fukuoka were still running, so I decided to stick to my plan. When I checked in to my hotel, I got evacuation instructions along with my keycard. TV reports showed emergency workers freeing trapped victims and carrying zipped yellow body bags. Officials spoke with tight, grim expressions.

The first game after the earthquake was canceled, but the second took place as scheduled. Waves of people came out, filling the stadium. I had expected some kind of pregame acknowledgment, a moment of silence at least, but at 1:00, the SoftBank Hawks unceremoniously took the field and the Tohoku Rakuten Golden Eagles’ first batter stepped to the plate.

The first seven innings featured some of the dullest, most error-ridden baseball I’d ever seen, as if after a tragedy of great magnitude, no one’s heart was really in it. Although the fan club in right field tried, even they had a certain forced feeling. Finally, with the listless Hawks down 7-3 and showing no signs of life, I decided to leave. I visited the Sadaharu Oh Museum, which celebrates the life and career of the man known as the Babe Ruth of Japan, and the team shop before catching the bus back to the city center. Somewhere along the way, I had the sudden feeling something was amiss. I patted my pockets and checked my satchel to confirm the loss. My Japan Rail Pass was gone. You could only buy it outside the country, and you needed to keep the physical pass on you. I was a bit ashamed to feel as aggrieved as I did given the devastating loss the people here had just suffered, but it was expensive, and I’d have to pay full fare to get back to Tokyo, so I decided to go back on the off chance I’d find it.

An hour had passed since I’d left when I got a taxi to go back, but the driver still had the game on his radio.

“The Hawks are still playing?” I asked.

He eyed me in the rearview mirror. “Tie,” he said. “Seven to seven.”

The Hawks had scored four times in the bottom of the ninth. I dashed back into the stadium, where the fans who’d stayed were on their feet waving rally towels and a team band banged taiko drums and blew horns as the teams slugged it out in extra innings. The Hawks were down to their last out in the bottom of the 12th (in Japan, games are declared a tie after 12 innings) when their 32-year-old outfielder Yuki Yoshimura, whose three-run pinch-hit homer in the ninth had evened the score, hit a walk-off blast to win the marathon contest.

Mic’d up in the outfield, Yoshimura addressed the fans. Japan calls these postgame exchanges the “hero of the game” interview. The whole place was silent as he spoke. A woman next to me translated, though I hardly needed her help.

“I know I’m just a baseball player, and we can’t do much,” Yoshimura said, “but we know the people of Kyushu are suffering and they won’t quit, and we were never going to quit, either.”

I admired him for being able to speak even more than for what he’d done in the game — though later, when a television reporter asked him a question, he covered his face in his palms and sobbed.

It put the loss of my rail pass in perspective. Still, after the stadium exploded fireworks that reverberated dreadfully under the closed dome, and after the fans performed the ritual of releasing oblong yellow balloons in the air, so symbolic of letting it all go, I decided to check the lost-and-found — because you never know.

And, this being Japan, someone had, of course, turned it in.

Originally published on Travelandleisure.com.

Todd Pitock’s last piece for the Post was “A Discouraging Word” (Argument, May/June 2017).

This article is featured in the March/April 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

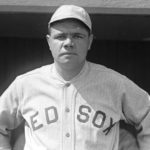

Babe Ruth and The Post

Babe Ruth

Given Name: George Herman Ruth Jr.

Born: February 6, 1895, Baltimore, MD

Died: August 16, 1948, New York City, NY

Position: Pitcher/Outfielder

Baseball Career:

• Boston Red Sox, 1914–1919

• New York Yankees, 1920–1934

• Boston Braves, 1935

More than just an icon of American baseball, Babe Ruth was also a showman, a gambler, a humanitarian, and an international ambassador of baseball. Read some of The Saturday Evening Post’s reporting on the Great Bambino, the Sultan of Swat, and the Colossus of Clout — George Herman Ruth Jr.

Babe Ruth’s Beginnings

In talking about himself, the Babe wishes to make it clear that he has been both bad and good. In this 1931 profile, Babe Ruth describes growing up in an orphanage and his lucky early break.

Babe Ruth: The Homely Hero

Ruth was a natural — truly comfortable fielding, pitching, and (especially) hitting. His records are well-known, but his over-sized personality has been flattened over the decades, and the quick glimpses we get of him today as an overweight, ungainly, hard-drinking yokel don’t do him justice.

Babe Ruth’s Compassion

In a now-famous story, Babe Ruth made an unscheduled trek to the country to comfort a young, sick child who was one of his greatest fans..

Babe Ruth’s Compassion

This article and other features about baseball can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, Baseball: The Glory Years. This edition can be ordered here.

In Vicksburg one rainy morning about 8 o’clock an aged, bewhiskered man with wet clothing and muddy feet came into the lobby of the hotel.

At the desk he asked for Babe Ruth. He was given the number of Ruth’s room on the second door at the head of the steps. That hotel had not yet surrendered to the idea of visitors’ having to be announced. A few minutes later Ruth, in bed, heard a rap at his door. He grunted and got up. In night clothes and with hair tousled, the Babe went to the door.

“I’m sorry to disturb you like this, Mr. Ruth,” the old gentleman apologized, “but I have come to ask of you a great favor.”

“What is it, old-timer?” asked Ruth, somewhat puzzled, but immediately sympathetic. “Sit down.”

“Mr. Ruth,” the stranger explained, “I want to get you to sign this baseball. It’s for a little boy out in the country — very sick. He may not get well. Ever since last fall, when we heard that the Yankees were coming here to play a game, the little fellow has looked forward to seeing you. Now that he knows that he can’t get out of bed, his mother thinks the disappointment has made him worse. She is very much distressed. I figured out that it would help some if I could get you to sign this ball. That would at least comfort him for a while.”

“Where is the little fellow?” asked Ruth.

“He lives out in the country about 12 miles. It was quite a trip for me, too, with all this rain and bad roads.”

“Sure, I’ll sign two or three balls for him,” declared Ruth. “Not only that, but I’ll take them to him. Let’s go!”

As the astonished old gentleman looked on, Ruth called for a bellboy, ordered a big touring car, and began to get dressed. Two hours later he arrived at the little boy’s home. The mother, instantly recognizing Ruth, could hardly believe her eyes. Without any preliminary conversation, she led the Babe immediately to the little fellow’s bedroom.

At the expression on the little boy’s face, as he raised up in bed, the mother burst into tears.

“He’s been delirious,” she said, “and he thinks he’s dreaming.”

“No, mamma,” spoke the boy. “It’s Babe Ruth himself, isn’t it?”

Ruth went over and sat on the side of the bed. Taking three baseballs from his pocket, he began signing them, all the while talking to the little fellow, as a pal, about the game. He asked about the boy’s own ball club and made several suggestions as to how they should play next summer. It was the happiest moment of that boy’s life.

“He’ll get well, all right,” Ruth said to the mother, in the presence of the little fellow, “and this summer he’ll be out there hitting that baseball as hard as any of them.”

Nobody knew of this incident — that is, nobody in our party — until we were aboard the train en route to Jackson that night. The writer of this happened to pick up a local afternoon paper, and on the front page found the story as just related, evidently told to the editor by the old gentleman.

“Certainly it’s true,” said Ruth, when asked about it. “That’s as little as anybody could do, isn’t it?”

All of us took the clipping and telegraphed it word for word to the papers we represented. Ruth felt a little hurt, and so did we, two or three weeks later, when a cynical paragraph in a distant newspaper referred to this incident as another bit of Ruth publicity.

—“And Along Came Ruth” (4-part series) by Bozeman Bulger, November–December 1931

Babe Ruth’s Beginnings

This article and other features about baseball can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, Baseball: The Glory Years. This edition can be ordered here.

In talking about himself, the Babe wishes to make it clear that he has been both bad and good, and that his real name is George Herman Ruth, and not Ehrhardt, as has been often stated in the question-and-answer departments of newspapers. The late Jack Dunn, owner and manager of the Baltimore ball club, called him George until the players had unanimously decided on “Babe,” and made it stick.

“In those days,” Ruth explains, “Dunn was always digging up youngsters for tryouts with his ball club. When

Brother Gilbert and myself came out of Jack’s once after they had signed me to a baseball contract 18 years ago, the players saw me from a distance. ‘There’s another one of Dunn’s babies,’ one of them remarked. The minute I put on a uniform they called me Babe and, in baseball, I have never known any other name. I’m not kicking, though. I rather like it. I was such a big fellow that the nickname of Babe struck the other boys as funny. I guess it would still be funny if we hadn’t all got used to it.”

“How long do you expect to play ball?” he was asked.

“I figure that about two more years ought to do me, but you can’t tell about that. You know how it is. Clark Griffith may have been right when he said that no ballplayer ever voluntarily quits the game until they cut the uniform to him. Anyway, I won’t be in there until I trip on my whiskers and the boys begin feeling sorry for me. I won’t have to do that.”

“What’s the most money you ever made in one year, Babe?”

He rubbed his freshly shaven face in an effort to remember. “About $130,000 — that is, counting baseball salary, exhibition work, stage appearances, syndicate writing, and so on. And, boy,” he chuckled, “you ought to see how I managed to scatter that chunk.”

“Did you ever try to figure how much you have earned altogether since you began playing professional baseball 18 years ago?”

“Oh, my average has been better than $50,000 a year. I’ve made at least a million dollars. Threw away more than half of it too. Had a lot of fun, though.”

“Did you have any aim in life, or any particular thought to the future, when you started out as a ballplayer?”

“No, of course I didn’t. I just wanted to play ball. I still like to play, even if it’s just for the fun of it. When I got my first job it seemed funny to me that anybody would pay me money to play ball.”

“Which do you get the most thrill out of — your pitching or your hitting?”

“That’s hard to say,” he replied after some thought. “I don’t believe I could ever get any more thrill than I did in pitching those scoreless innings in the 1918 World Series back in Boston. Still, anybody gets a big kick out of taking a cut at that ball and hitting it on the nose. Anyway, I know the public gets a bigger kick out of seeing a fellow hit ’em than in seeing him pitch ’em. Why, take a 60-year-old golfer, for instance. Nothing in the world gives him such a thrill as clipping that golf ball on the button with a full swing. They’ll tell you the science of the fine shots is what counts, but that’s all baloney. What counts in their lives is socking that ball and giving it a ride.

“Now, the records will show that I was a pretty good pitcher. You never hear much about that, though… The kids know me as a home-run slugger.”

During the past World Series in 1931 Ruth sat beside the writer in the grandstand at St. Louis, experting on the big games. “Mr. Ruth,” interrupted a pleasant-voiced young lady, “will you please autograph this program for me? My uncle was a ballplayer and — ”

“OK,” said the Babe, scrawling his familiar signature and passing it back over his shoulder. “Now I’m in for it,” he confided out of the corner of his mouth; “they’ll keep this up for an hour.”

And they did. Protesting ushers were swept aside in the rush. The autograph seekers were in attacking formation. They brought programs, rain checks, toy bats, notebooks, hatbands — everything — to be decorated with the Ruth signature. After a half hour his hand was so badly cramped that he demanded a rest.

“First thing you know,” he said, “ some bird will be asking me to sign his socks.”

“Listen,” Ruth finally warned his increasing admirers, “I’m going to stop when play starts. You know, I want to see some of this ball game myself.” That merely served to accelerate the rush.

The amplifiers finally announced the first batter.

“No, that’s all,” the Babe resolutely denied the next applicant. “No more till tomorrow. None after the game either.”

“Can’t you sign this baseball, Mr. Ruth?” a rather weary voice spoke behind him.

“No, no. I turned down the others. Come out before the game tomorrow. I’ve been doing this for an hour now. Got to see the ball game.”

“I’m sorry,” explained the voice. “I had to come up on crutches and just got here.”

“What’s that — crutches? Well, that’s different.” His big hand reached back for the ball and he carefully inscribed his name. “Sorry you had so much trouble. You’re welcome. That’ll get me in trouble sure,” came in an undertone from the corner of his mouth.

“Won’t you please sign this score card?” immediately spoke a feminine voice. “My father owns a baseball club out West. Won the pennant.”

“All right. Hand it over.” And down went the signature, with the added comment: “Good luck to the Indians.”

With these two exceptions he stuck to his refusal and called it a day.

Today Ruth looks back on St. Mary’s, the orphanage where he was raised, as the real home of his early boyhood. The memories of it are very dear to him. “You know,” he said, during a later lull in the ball game, “I was not an orphan when I went to St. Mary’s. My parents were living, but they were very poor. I went to that school the first time when I was only 6 years old. The second time they sent me I stayed there. Oh, yes, I guess I was a truant, all right, and needed to be taken there, but many boys who went there were not bad boys or truants. They were sent by their parents to St. Mary’s just to learn a trade. It’s a great school.”

“What trade did they select for you?” I asked him.

“Oh, I was a shirt maker — darn good one too. That’s why they can’t fool me about shirts to this day. I know how they are cut and how the parts are put together. I worked at an electrical machine which stitches the parts of a shirt together. I was the best one in the school,” he added, with a touch of pride.

The boys at St. Mary’s were not long in discovering that George Ruth, as they knew him then, could throw a baseball harder and hit one farther than any other kid in school. Ruth is very much in doubt as to what position he played at first. “Oh, I just played ball and played in any position they’d let me. I’ve been outfielder, infielder, catcher, and pitcher. It made no difference to me. You know how it is with boys.”

In time Ruth developed so much prowess as a pitcher that he was assigned to that job regularly. It was his remarkable showing as a left-handed pitcher that influenced Brother Gilbert to speak to Jack Dunn, owner and manager of the Bal- timore club, about him. “You can bet I will never forget that day,” says Ruth. “Boy, that was a thrill! After Jack Dunn had talked to me for a few minutes they gave me a sort of tryout in the yard. I guess Jack decided that I had something.”

Brother Gilbert explained to Ruth that boys played ball for fun, but that he was now taking a man’s job that called for business arrangements. “Mr. Dunn has agreed to pay you $600 for the six months of the playing season,” Brother Gilbert told Ruth. “That is $100 a month, or about $25 a week. Would you be satisfied with that, George?”

Ruth says that he would have been satisfied to play baseball for nothing, as long as he had a place to eat. Six hundred dollars was about the largest sum of money his mind had ever contemplated. “I got a big kick out of winning my first World Series game,” he says. “It was another kick when I established that record of the most scoreless innings pitched in a World Series. And you know my feelings when I hung up that home-run record for the Yankees. But I’m telling you, the biggest kick I ever got was when I walked out on that field that day and told the other boys that I had signed a contract and was now a real, honest-to-goodness professional ballplayer and was going to get paid for it.”

Babe’s recollection is that Manager Dunn raised his salary at the end of the second month, making his total for the season $1,800. Never having known anything about the value of money and never having had possession of more than two or three dollars at a time, this $300 a month seemed to the Babe an enormous sum. The players on the Baltimore club found this big, gawky youth one of the most generous-hearted souls they had ever met. He would give them his shirt if they wanted it. If he had $100 in his pocket, he would bet it on a horse race just as quickly as if the amount had been $5. The Oriole players hated to see him go, but they knew that he was bound to go sooner or later. And they were right.

Before the end of that season — 1914 — Ruth had joined the Red Sox. In Boston they gave him a contract calling for $3,500 a season. Besides learning the finer tricks of baseball, Ruth wanted to learn what the boys in fast company did for amusement in their o hours. His education in that respect was rapid indeed. e world had opened up for the Babe and he wanted to examine its inside to see what made it tick.

Probably the greatest sense of freedom and well-being that Ruth had ever enjoyed up to that time was his first experience as a guest in the hotels patronized by the Baltimore club. The elevators fascinated him. He rode them up and down for the sheer joy of it. His first adventure into the fast life was the acquisition of a bicycle, obtained temporarily from a messenger. As a consequence, he got the habit of sneaking off for a trip of exploration occasionally, much to the worry of Manager Dunn. Finally Dunn called a stern halt to Babe’s excessive riding on elevators and bicycles.

One of the early uses for money as discovered by the Babe was an unrestrained indulgence in hot dogs. Before, during, and after the games he bought and consumed them. He would now but for a rigid diet decree that he reluctantly obeys. After Ruth became famous, one of his attacks of indigestion was attributed to his consumption of 11 hot dogs and three bottles of soda pop in one afternoon at the ball park.

One day, in a batting practice just before the game, Ruth hit a liner that cleared the right-field fence like a bullet. The grandstand buzzed with the wonder of it. Long before that, however, the players had been talking about this natural hitter with such perfect form. To the wonder of experts, this big kid could take a full swing with a bat, gripping the handle at the extreme small end, and time the ball with as much precision as if he had chopped it.

Up to that time it had been the batting theory that a full swing lessened the hitter’s accuracy and gave the pitcher all the advantage. There were a few exceptions, but most of the great hitters used the short or chop swing, and stepped forward to meet the ball in front of the plate. By taking a chop swing they could keep their eye on the ball all the time and not be thrown off balance by a violent swing. Ruth upset all that. His perfect eyesight, his sense of timing and his muscles were so coordinated that he could take a shoestring swing and throw the full weight of his big body behind the wallop with precision. Ruth’s demonstration of such power in natural rhythm was the forerunner of the home-run fad that made a revolutionary change in the game. Others began trying it, and even the kids on the sandlots caught the fence-busting craze. Even so, it was a long time before the best baseball minds thought of Ruth as a regular batter. He was regarded as a freak. They marveled at the terrific force of his drives, but continued to think of him as a pitcher rather than as a batter.

Though he developed into a masterful pitcher and holds the record of having pitched 29 consecutive scoreless innings in a World Series (1916 and 1918), Ruth was not an object of hero worship, nor did he come into riches, until he began to hit his home runs.

In 1918, Ed Barrow, a veteran baseball man, was manager of the Boston Red Sox. In Ruth he knew that he had a great pitcher, but when the Babe began to hit home runs with marked regularity in 1918, Barrow saw that he might be more effective as a hitter than as a defensive player. Also his keen mind had noted the eagerness of the fans to see Ruth bat, even when he was pitching masterfully.

Before the next season came around, the farseeing Barrow had made up his mind. The season of 1919 found Babe Ruth one of the regular out elders. All baseball watched the experiment with keen interest, a few openly doubting its success. Ruth had established a world’s record by pitching. Still, Barrow had to consider that a pitcher would be inactive about four days out of five. “Can’t keep a man like that on the bench,” decided the manager, and he was wise.

In appreciation of his work as a pitcher as well as a hitter, the Boston club raised Ruth’s salary from $7,000 to $10,000 and gave him the three-year contract. That was the contract that the New York Yankees eventually bought.

In the spring of 1919, Ruth hit 29 home runs, a new world’s record. To appreciate the impact of that accomplishment, you need only look back six years earlier. In 1913 when Frank Baker of the Athletics had hit 12 home runs, it was regarded such a marvelous performance that he earned the sobriquet of Home Run Baker.

Ruth’s longest home run of record was made in Tampa, Florida, in an exhibition game between the New York Giants and the Boston club in the spring of 1919. This game was played in a race-track inclosure. The ball hit by Ruth not only went over the outer circle of the track but cleared the distant barns and fell into a sort of park in front of the Tampa Bay Hotel. The distance covered by this long drive was so unbelievable that a group of Boston and New York writers got a tape line and measured it. From the home plate to the point where the ball struck the ground was exactly 508 feet.

At the end of the 1919 season, in which Babe Ruth had shattered all home-run records, Harry Frazee, owner of the Red Sox, was in financial straits. He agreed to turn Ruth’s contract over to the New York club for $100,000 in cash.

When the deal had been finally consummated and Ruth had become the property of the New York club, practically every newspaper in the big city carried the news on the front page under glaring headlines. New York dearly loves a hero, and here was one made to order. The fact that much was expected of him and that the eyes of a great city were upon his every move did not in the least disturb Mr. Ruth. Reporting to Manager Miller Huggins for spring practice, Ruth began hitting home runs in the exhibition games and kept it up right to the end of the season. Long before the summer was over the Bambino, as Ruth came to be called by his Italian admirers, and then by everybody, had passed his world’s record of 29 home runs and was onto a new mark. At the end of the 1920 season, Ruth had astounded all baseball by making 54 home runs. This was an average of a fraction more than one for every three games.

With his mad rampage of home-run hitting, attendance at the Yankee games increased in jumps. A few years earlier, it was considered worthy of note for a major-league ball club to play to more than 500,000 spectators in a season. With the coming of Ruth, the Yankees eventually passed the 1 million mark.

Flush with box office receipts, the owners bought a big plot of ground in the Bronx across the river from the Polo Grounds and built a stadium costing more than $2 million. Though this structure is officially called the Yankee Stadium, it is frequently, and justly, referred to as The House That Ruth Built. An architectural feature of great satisfaction to the Babe was the close proximity of the kitchen, where the hot dogs are concocted, to the players’ bench.

The Yankee owners, in appreciation of what Ruth had done for the club, voluntarily raised his salary to $30,000 for the season of 1921.

—“And Along Came Ruth” (4-part series) by Bozeman Bulger, November–December 1931

Babe Ruth: The Homely Hero

August 11, 1929: Babe Ruth becomes the first ball player to hit 500 home runs.

by Bozeman Bulger

November 28, 1931

Everybody knows the Babe. The great Bambino comes up whenever fans discuss the baseball greats. Ruth was a natural—truly comfortable fielding, pitching, and (especially) hitting. His records are well-known, but his over-sized personality has been flattened over the decades. The quick glimpses we get of him today present an overweight, ungainly, crude yokel, extremely fond of beer, hot dogs, parties, and female companionship. The picture doesn’t do him justice.

In 1931, the Post offered a four-part series on the Babe, entitled “And Along Came Ruth.” It explained a lot about Ruth, including what made him a hero to America. First, though, it gets the nickname out of the way.

“ ‘In those days,’ Ruth explains, ‘Dunn [Jack Dunn, owner and manager of the Baltimore ball club] was always digging up youngsters for try-outs with his ball club. When I came out of Jack’s office after they had signed me to a baseball contract eighteen years ago, the players saw me from a distance. ‘There’s another one of Dunn’s babies,’ one of them remarked. The minute I put on a uniform they called me ‘Babe’ and, in baseball, I have never known any other name. I’m not kicking, though. I rather like it. I was such a big fellow that the nickname of ‘Babe’ struck the other boys as funny. I guess it would still be funny if we hadn’t all got used to it.”

Being called “Babe” was appropriate for George Herman Ruth Jr. Newspaper articles from the 1920s and 30s give us the impression he was very much a big kid. He enjoyed sports. He golfed and spent a lot of time watching baseball, polo, and horse racing. He enjoyed wandering around cities on a bike, cruising around in a fast car, or taking ride after ride in elevators.

He had a simple, yet sharply accurate, way of speaking, much like any street kid from the time. Once, in 1930, a reporter asked Ruth about how he could justify earning more that year than President Herbert Hoover ($80,000 to Hoover’s $75,000), since he was just a professional baseball player. Ruth replied, “What the hell has Hoover got to do with it? Besides, I had a better year than he did.”

In the off season, Ruth would also go barnstorming: playing exhibition games in farm towns. He did this more frequently than any other player at the time, and he’d put on as big of a show as possible to make sure everyone had a good time. He once said about it, “Got to be friendly with folks like that … Besides, no one could ever earn 70 or 80 thousand bucks a year by being a crab.”

“Ruth is often hard put to remember the name of his opponent, but that is no check on his friendliness. He disposes of this problem in a way that is generally satisfactory, if not perfect. All men under the age of forty are addressed by Mr. Ruth as ‘Kid.’ [pronounced “keed”] Those who have gray hair or wear spectacles are ‘Doc.’ Rarely do they fail to answer to their names.”

Early in the interview, the Post writer asked Ruth how long he expected to keep playing baseball. “I figure that about two more years ought to do me, but you can’t tell about that. You know how it is. Clarke Griffith may have been right when he said that no ball player ever voluntarily quits the game until they cut the uniform off him. Anyway, I won’t be in there until I trip on my whiskers and the boys begin feeling sorry for me. I won’t have to do that.”

The interviewer asked, “Which do you get the most thrill out of—your pitching or your hitting?” ‘That’s hard to say,’ he replied after some thought. ‘I don’t believe I could ever get anymore thrill than I did in pitching those scoreless innings in the World Series back in Boston. Still, anybody gets a big kick out of taking a cut at that ball and hitting it on the nose. Anyway, I know the public gets a bigger kick out of seeing a fellow hit ‘em than in seeing him pitch ‘em.’ ”

Ruth terminated the first interview abruptly after he checked his watch. “Listen,” he suddenly exclaimed, “I’ve got forty minutes to report at the ballpark. Always try to be on time. Young fellows seeing me late might think I’m trying to get away with something. The older and more prominent you get in baseball the closer you’ve got to follow the rules. Don’t you think so?”

Babe Ruth was a soft touch when it came to children, even tolerating kids who clung to his moving car or pressed their faces on restaurant windows just to get a glimpse of their hero. Once, in 1929, Ruth attended a World Series game in which he was not playing and found himself inundated with hundreds of eager people asking for his autograph. He obliged, but declared that once the game started, he would not sign any more autographs. When the starting batter was announced, Ruth said “No, that’s all. No more till tomorrow. None after the game either.” Then he heard a weak voice say, “I’m sorry. I had to come up on crutches and just got here.” Ruth, with more care than with all the other autographs, signed the kid’s ball after saying, “What’s that? Crutches? Well, that’s different.”

“The boys of this same nation look on Babe Ruth as a pal. They have the feeling of knowing they can meet him at the gate, can climb on his back, can clamber on the running-board of his automobile, can get him to sign a baseball. To them, Ruth is still just another boy, and he feels exactly the same way about it. His sympathetic understanding of these kids is no pose. Ruth really likes the association, and they know it instinctively. He feels it a keen responsibility to keep faith with his youthful admirers.”

Legend seemed to gather naturally around Ruth. Some of them seemed fantastic and improbably sentimental, but they were too numerous to simply be inventions. For example, the story of the handicapped boy in Florida:

“The baseball grounds in Tampa are within a race-track enclosure, the same grand stand being used for both sports. It is customary for many spectators to arrange themselves around the circular track and watch the ball game from automobiles. On this particular day a father had parked his car near the press box on the lawn, so that his little boy, almost completely paralyzed, could see Babe Ruth. The cushions were so arranged that the little boy could look over the edge of the car and see the players. At first his eyes alone expressed his interest. Finally Babe Ruth appeared to take his turn at bat.

“ ‘There he is, daddy! There he is, daddy!’ exclaimed the excited youngster. Moreover, to the astonishment of his father, the lad tried to raise himself to see better, and partially succeeded.

“It so happened that Babe Ruth hit a home run. ‘At-a-boy, Babe! At-a-boy, Babe!’ shouted the lad in the general excitement.

“The father looked around, and to his further amazement the little boy had raised himself almost to a sitting position—the first time he had been able to do such a thing for a year.

“ ‘It’s all right, son. It’s all right, son,’ cautioned the overcome father, and as he repeated the phrase he wept. ‘Lie down now. But we know you will be able to sit up! Son, you did it!’

“Ruth, hearing of the incident a few minutes later, went over and shook hands with the little boy.

“ ‘You have made him very happy, Mr. Ruth,’ said the father, ‘and I want to thank you. This is a big day in his life. It may really help him to recover.”

“ ‘Bet your life he’ll make it,’ said Ruth, ‘and more power to him.’ ”

And there’s the one about the boy in Mississippi, which could happen only in cheap fiction or real life:

“In Vicksburg one rainy morning about eight o’clock, an aged, bewhiskered man with wet clothing and muddy feet came into the lobby of the hotel. At the desk he asked for Babe Ruth. He was given the number of Ruth’s room on he second floor at the head of the steps. That hotel had not yet surrendered to the idea of visitors’ having to be announced. A few minutes later Ruth, in bed, heard at rap at his door. He grunted and got up. In night clothes and with hair tousled, the Babe went to the door.

“ ‘I’m sorry to disturb you like this, Mr. Ruth,’ the old gentleman apologized, ‘but I have come to ask of you a great favor.’

“ ‘What is it, old-timer?’ asked Ruth, somewhat puzzled, but immediately sympathetic. ‘Sit down.’

“ ‘Mr. Ruth,’ the stranger explained, ‘I want to get you to sign this baseball. It’s for a little boy out in the country—very sick. He may not get well. Ever since last Fall, when we heard that the Yankees were coming here to play a game, the little fellow has looked forward to seeing you. Now that he knows that he can’t get out of bed, his mother thinks the disappointment has made him worse. She is very much distressed. I figured out that it would help some if I could get you to sign this ball. That would at least comfort him for a while.’

“ ‘Where is the little fellow?’ asked Ruth.

“ ‘He lives out in the country about twelve miles. It was quite a trip for me, too, with all this rain and bad roads.’

“ ‘Sure, I’ll sign two or three balls for him,’ declared Ruth. ‘Not only that, but I’ll take them to him. Let’s go!’

“As the astonished old gentleman looked on, Ruth called for a bellboy, ordered a big touring car and began to get dressed. Two hours later he arrived at the little boy’s home. The mother instantly recognizing Ruth, could hardly believe her eyes. Without any preliminary conversation, she led the Babe immediately to the little fellow’s bedroom. At the expression on the little boy’s face, as he rose up in bed, the mother burst into tears.

“ ‘He’s been delirious,’ she said, ‘and he thinks he’s dreaming.’

“ ‘No, mamma,’ spoke the boy. ‘It’s Babe Ruth himself, isn’t it?’

“Ruth went over and sat on the side of the bed. Taking three baseballs from his pocket, he began signing them, all the while talking to the little fellow, as a pal, about the game. He asked about the boy’s old ball club and made several suggestions as to how they should play next summer. It was the happiest moment of that boy’s life.

“ ‘He’ll get well, all right,’ Ruth said to the mother, in the presence of the little fellow, ‘and this summer he’ll be out there hitting that baseball as hard as any of them.’

“Nobody knew of this incident … until we were aboard the train en route to Jackson that night. The writer of this happened to pick up a local afternoon paper, and on the front page found the story as just related, evidently told to the editor by the old gentleman.

“ ‘Certainly it’s true,’ said Ruth, when asked about it. ‘That as little as anybody could do, isn’t it?’

A few days later, a journalist on a big city paper wrote that he doubted the story. He boldly stated that the whole incident had been manufactured by a publicist. Ruth, who had never sought any notoriety for the incident, felt crushed by the accusation.

Babe Ruth went well beyond his 500-homer record. When he retired in 1935, he had 714 home runs to his credit. His record remained unbroken for 39 years, until the great Hank Aaron surpassed him in 1974.

The home-run record is now held by Barry Bonds, with 762 homers. Bonds’ accomplishment has been diminished by allegations of his using performance-enhancing steroids. There are no allegations, of which we know, that he has been visiting sick children and signing baseballs for them simply for the publicity.