Cartoons: The Funny Thing About Marriage…

In the wise words of Ben Franklin, “Keep your eyes wide open before marriage, half shut afterwards.”

Mar/Apr 1999

Jul/Aug 1998

Mar/Apr 2003

Jan/Feb 2007

Jan/Feb 1998

Jan/Feb 2002

May/Jun 2000

Cartoons: The Office

The cure for a hard day at work? Laughing about it, of course.

Cartoons: Let’s Talk Turkey

Let’s give thanks to those who make us laugh!

Can Government Censorship Be a Good Thing? 75 Years Ago This Week

In this editorial from January 24, 1942, the Saturday Evening Post analyzed the role of wartime censorship implemented by the Office of Censorship and extended by the cooperation of newspaper editors. The assumptions in this editorial — that the citizens will trust the government to censor information as it sees fit, that the press and the politicians can find mutually agreeable terms of censorship, that the press will exercise discretion in what it chooses to publish — would be unlikely to find much support today.

The Post noted that wartime censorship required “a pledge of unlimited confidence to be exchanged between the Government and the people.” While this point of view may have found favor 1942, it’s doubtful that Americans would agree with this sentiment 75 years later, even if we found ourselves in similar circumstances. Whether you call it cynicism or wisdom, too much has changed.

Censorship

Originally published January 24, 1942

It says much for the powers of self-discipline in a free and willful people that liberty of the press very willingly submits to put itself in a strait jacket for the duration of the war. Everyone uncomplainingly takes it for granted that communications will be censored and that news will be controlled at the source, and that this will be done not as the law says it may be but as military judgment says it shall be. Censorship on those terms requires a pledge of unlimited confidence to be exchanged between the Government and the people; and so, happily, it begins. But we shall do well at the same time not to underestimate the difficulties.

The Government lays down what appears to be a very legible rule to govern the release of news. The conditions are two. First, the facts must be fully verified; second, publication of them is forbidden if they tend in any way, direct or indirect, to give aid and comfort to the enemy. But you could not invent a general rule that would leave more to arbitrary discretion in its application to a particular case.

News is of two kinds — good and bad. Any bad news at all tends to give aid and comfort to the enemy. Then what will you do with it? Withhold it from the people until it is certain that the enemy already has it?

Take the communiqué. In its daily report to the people the Government cannot tell everything that has happened, and the more critical the situation is the more this will be true. Why? Because the enemy is reading it too. You cannot have two reports — one for the people and one for the enemy.

In the business of bombing, for example, the enemy’s only firsthand knowledge of his hits is from his own pilots, who tend naturally to exaggerate what they think they have done and are liable in any case to be mistaken. The enemy, therefore, anxiously watches the news on the other side in order to check the claims of his own pilots; and one of his artful tricks is to put forth fantastic claims in his own communiqué with intent to provoke on the other side a denial, on the chance that the denial will be informing. Thus, it was very important for the Japanese to know whether or not they had got an aircraft carrier at Pearl Harbor, as their own pilots said they had.

The communiqué, indeed, now is one of the weapons of strategy. The Russians in theirs were most despondent just on the eve of the unexpected counteroffensive that forced the German war machine suddenly into reverse. The purpose was probably twofold. One part of it was to deceive the Germans; the other was to hasten American and British aid.

On the free, Anglo-American side there is no likelihood of bad military news being suppressed or long withheld for fear the people cannot take it. The British are extremely the other way. They are nourished by bad news. “It must be remembered,” said Mr. Churchill, in a recent review of the war before the House of Commons, “that here at Westminster and in Fleet Street” — newspaper row — “it has been sought to establish the rule that nothing must be said about the war that is not altogether discouraging. Although I must admit the British people seem to like their food cooked that way, a military spokesman addressing a large army might do more harm than good if he always put things at their worst, and never allowed buoyancy, hope, confidence and resolve to infect his declarations.” He was defending the military spokesman at Cairo, whose reports on the North African campaign, the English people thought, had been disgustingly optimistic, and they were complaining of him on that ground.

But there is another kind of bad news which, although it is not strictly military in character, does tend nonetheless to give aid and comfort to the enemy; and the question about it is not whether the people can take it but whether the Government can, because it is news of the Government, of its own blunders and failures and mistakes of political judgment. What will the censor do with facts of that order? What ought he to do with them?

This is the kind of news that free criticism tends to reveal; and here it is that censorship faces what is perhaps its most unruly problem. For all the aid and comfort it may afford the enemy, shall criticism be free? In England it is. Mr. Churchill has at times complained of it, yet very mildly and with grim understanding. Suppression of criticism would be incomprehensible in England. So it would be here. Free criticism is troublesome. It does present a problem. Nevertheless, it is one that will solve itself if let alone. A government in the popular principle, being trusted by the people to control their news at the source and censor their communications for military reasons, must in turn trust criticism to censor itself. And this it does much more than can be realized by those who know only when it errs and have no idea how many times it makes the right answer when it asks itself this question: All things considered, will the saying of this truth do more good than harm? And if, in a given case, it comes too often to the wrong answer, then people themselves by their extreme disapproval will extinguish it, with no aid from the censor.

Good news, you might suppose, offers the censor no problem at all. Nevertheless, good news can be a liability. People may make too much of it. Bad news moves them to greater exertion, whereas good news may tempt them to relax. In his very fine sermon on “must” to the representatives of labor and management just before they sat down to work out a truce for the duration of the war, President Roosevelt said: “Don’t believe everything you read in the newspapers. … I was reading a paper this morning which was telling how inevitable … a victory would be. I want to see what we can do.”

To be on the safe side, we must expect a long hard war. News tending to belittle the resources of the enemy or to make us complacent about our own must be discounted. How? Not by suppression and certainly not by distortion, but by mixing bad news with good, by emphasis, by keeping the facts in perspective. Thus you come to censorship policy, touching the handling, timing and spacing of the news, for its effect upon public morale.

The poet said, “Let me write the ballads of the people and I care not who may write their laws.” This was paraphrased by a New York managing editor who said: “Let me write the headlines and anyone who likes may write the ballads.” He would not touch a word of the news to alter it, nor would he write a false headline. He would produce his effects entirely by selective emphasis. If there could be anything like that power of propaganda in mere headlines, and truthful headlines at that, imagine what lies in the hands of a censor, a national managing editor, acting upon news at the source, not to change any of the facts, but to time the release of them, to counterweight good ones with bad ones, and so control the perspective. Whose perspective? Not his own. The censor has no policy of his own. He executes the government’s policy, and when he fails to do that, there is a new censor.

Censorship is unavoidable. Although it may be authorized by a wartime statute, and is in that sense lawful, it cannot be administered by any rule of law. You may read in the Constitution that the Congress shall pass no law to abridge freedom of speech or freedom of the press; but when drums beat, the law flies away, says the proverb. Moreover, censorship entirely innocent of propaganda belongs to some faraway realm of the ideal. The subtle power of propaganda that is implicit in control of the news is bound to be exercised, because, first, a government is human, and for the reason besides that every government is obliged to believe that it knows what is best for the total good.

This is our second experience. In the war before, it was the Committee on Public Information. Now it is the Office of Censorship, which has a more honest and a more severe sound and, we suppose, a more severe intention. Even so, there will be, we think, forbearing to almost any point, no want of co-operation and no unfair criticism, so long as the Government holds free of hurt and trespass that confidence with which people, both the believing and the unbelieving, have suddenly overwhelmed it.

How TV News Plays to Our Darkest Fears

Breaking news: Something terrible has happened out there … calamitous … innocents have perished … it is beyond horrific. Instantly, TV newsrooms across America crackle. Adrenaline pumps. The on-camera anchors are visibly jazzed.

Excuse me? Jazzed? Ladies and gentlemen, we have descended into the apocalyptic universe of 24-hour cable, where bad news is good news and extremely bad news is the best news of all, meaning there will be year-end staff bonuses. Which raises the question: What kind of demented people are we?

We are a cable-news-watching people, that’s who. A few weeks ago I heard Robert Bryce, author of the book Smaller Faster Lighter Denser Cheaper, declare on a talk show that millions of Americans “aren’t happy unless they’re scared and miserable.” I assume he wasn’t just talking about devotees of Larry King’s vitamin infomercials. Fact is, the big cable channels incessantly tease the thrill of catastrophe: Either it’s about to happen or it just did. Scared yet?

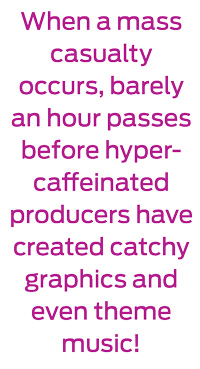

When a mass casualty event occurs — the Newtown shootings, say, or the downing of the Malaysian airliner — barely an hour passes before hyper-caffeinated producers have created catchy graphics and even theme music for the miniseries they are rushing to launch. That’s either brilliant marketing or all kinds of icky, depending on your tolerance for revulsion.

“Personally, I hate that stuff,” says Michelle Kosinski, a longtime NBC News correspondent, now handling the White House beat for CNN. “The branding, the titles. It looks like a parody of news coverage.”

Blanketing one big story while short-shrifting others — as in CNN’s weeks-long Malaysia Flight 370 marathon — tends to attract viewership and mockery in equal measure. “After a few days of that kind of coverage, it can turn people off,” Kosinski says. Following a small Los Angeles earthquake in June, comedian Paula Poundstone tweeted: “Early reports say there was no dmage [sic] … but CNN will keep trying.” Ouch.

I reached out to a dozen TV insiders, and all agreed: What cable delivers on the heels of a tragedy may be unseemly and warped, but it’s also mesmerizing. “It always goes back to the mystery,” says Chris Ariens, managing editor of the TVNewser blog. “That’s the TV draw.”

“Why” is a reasonable thing to ask. However, “the country has many real problems, and the fixation on catastrophes amounts to so much wasted effort. It drives me crazy,” says Lauren Ashburn, a Fox News contributor. Terry Anzur, a TV-news coach who’s anchored for CBS and NBC, adds that, regrettably, cable news has degenerated “into a form of chicken.” It’s a game everyone is guaranteed to lose.

Look, there’s no gainsaying that the cable news crews have conspired to raise our national blood pressure. They giddily activate our night tremors because it means money, and because they can. The technology that allows cameras to go live anywhere, anytime is addictive. What news director is going to leave those cool toys in a box?

And almost always, we, the advertisers’ dupes — er, audience — will stay glued to the screen, no matter what. “When journalists are rewarded for viewership, there’s a perverse motivation to play into people’s attraction to freak shows and horror,” Danah Boyd, who works at Microsoft Research, wrote in an essay not long ago. She added that this occurs “regardless of the social consequences.”

Is there any way to defend the way cable gorges itself on these mortifyingly sad dramas? Probably not. “With all the new tools at our disposal, we might be better at chasing the moment, but we’re losing the meaning,” says Lisa McRee, a former co-anchor on ABC’s Good Morning America.

Maybe she should take it up with Leonard Steinhorn, a professor of public communication at American University in Washington, D.C., who argues that “these catastrophes are like Greek tragedies. TV understands our fears, our anxieties.” Ultimately, the professor says, the soap-operatic coverage of grand trauma “serves as a national binding experience.”

Only, of course, if we’re willing to be so bound. An alternative position is that, dependably, it’s not only tragic news that will keep breaking, but our collective national dignity as well.