You Be the Judge: Reader Favorite: Looking for a Fair Way

In 1977, Nebraska businessman and avid golfer Dennis Circo developed an exclusive residential neighborhood dubbed Skyline Woods. Its centerpiece was an 18-hole golf course. As the developer, Circo sold lots, built homes, and transformed the golf course into a country club, adding a clubhouse, pool, and tennis courts. With all of its amenities, buyers paid a premium for home lots.

By 1990, Skyline Woods was well established, with 90 homes built around the country club, and Circo thought the time was right to sell the club to a golf course management company. Unfortunately, the golf pros ran into financial hazards. They ran out of “green,” and the only course of action was for Skyline Woods Country Club to file for bankruptcy in 2004. To pay off debt, the bankruptcy trustee auctioned off the property in 2005. A group of Skyline Woods homeowners tried to buy the club, but were outbid by Liberty Building Corporation, a development company owned by David Broekemeier.

Here’s where things got sticky. The federal bankruptcy court transferred property to Liberty, free and clear of all obligations. Shortly after, Broekemeier met with homeowners and club members to inform them he had no obligation to honor memberships, offering the option to play the course if they paid fees like anyone else.

If that was bad, what happened next was worse. In spring 2006, Broekemeier closed the club, posted “no trespassing” signs, and began cutting down trees to clear land where he planned to build a condominium complex and water park. Teed-off homeowners sued Broekemeier in Nebraska State Court, requesting a restraining order to prevent further damage to the land. They claimed implied covenants as homeowners in the golf community guaranteed the only use of land was as a golf course.

They reasoned Broekemeier might own the golf course free and clear but was free only to use it as a golf course. Homeowners added that no matter how you slice it, Broekemeier was well aware of their covenants, as he had also built a golf community adjacent to Skyline Woods. And, like Circo, he marketed the course’s proximity and views to sell lots. And there were rumors that he was going to redirect the golf course toward his neighborhood, leaving Skyline Woods homeowners with views of condos and a water park.

In response, Broekemeier came out swinging with a motion to dismiss the case. His first argument was that the state court had no jurisdiction to interfere with the federal bankruptcy order. Second, even if the state court did have skin in the game, the covenants were unenforceable because they were never recorded. Finally, he said Nebraska law protects bona fide purchasers from restrictive covenants when there is no notice.

How Would You Rule?

District Court Decision — 2008:

Round one was won by the homeowners. A Nebraska court found that they did indeed have implied restrictive covenants; Broekemeier was aware of the covenants; and finally, the bankruptcy sale of the property did not discharge the covenants because they belonged to the homeowners, not the golf course. The court ordered Broekemeier to either reopen the golf course or maintain it in a fashion that would not devalue the property of homeowners. Broekemeier chose the latter.

Round two: After six years of legal turf wars, the golf course never reopened, eventually becoming an eyesore due to lack of maintenance.

Aftermath — 2012: Game over. The land was sold. At that time, the new owner planned to spend $7 million to build a premier golf course.

This reader favorite originally appeared in the July/August 2012 issue of The Saturday Evening Post and was republished in the May/June 2020 issue. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

The Company that Nearly Bankrupted America

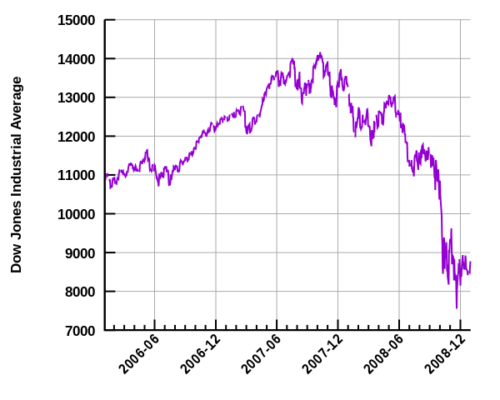

Science teaches us that whatever goes up must come down. Myths teach us that Titans fall. And history is full of warnings, indicators that can predict future success or failure based on the patterns of previous behavior. Sometimes, all of those lessons can be applied to a situation, particularly one that’s dire enough to be studied, and learned from, and potentially avoided in the future. That’s the case with Lehman Brothers. Before 2008, it was the fourth-largest investment bank in the United States and had been in business for more than 150 years. In September 2008, the company would declare bankruptcy with the largest filing in U.S. history, shaking the world economy and unveiling a tangled web of toxic assets, bad decisions, and litigation. What happened?

To understand how deeply woven Lehman had become in the financial fabric of America, you have to look at its origins. Lehman started as a dry-goods store in 1844. Founded by Bavarian immigrant Henry Lehman, and joined later by his two brothers Emanuel and Mayer, the company soon got involved in commodities trading when it began accepting raw cotton as payment at the store. The brothers started a second business focused only on trading, and it quickly outpaced the store. Henry died of yellow fever in 1855, but the brothers kept the commodities business going. Following the cotton trade as it shifted the center of its orbit to New York City, the brothers opened an office there in 1858.

As that business grew, it took on other markets, like coffee, and expanded into railroad bonds. The company was key in financing the reconstruction of Alabama after the Civil War. In 1889, it underwrote its first public offering. In the 1920s and ’30s, the firm underwrote dozens of further issues, including those for F.W. Woolworth, R.H. Macy & Company, B.F. Goodrich, The Studebaker Corporation, and many more. In a sense, Lehman became big simply by being big and thinking big; it enabled the launch of titans of industry and brands that became household names.

By the financially turbulent 1970s, Lehman had embarked on a series of mergers and acquisitions to stay alive. It acquired Abraham & Company in 1975, then merged with Kuhn, Loeb & Company in 1977. The newly rechristened Lehman Brothers, Kuhn, Loeb Inc. became the fourth-largest investment bank in the U.S. Shearson/American Express bought the company for $360 million in 1984; it in turn merged with E.F. Hutton & Company in 1988. All of this consolidation guaranteed that the renamed Shearson Lehman Hutton would remain a strong institution, but it was also emblematic of the enormous financial power being concentrated into the hands of fewer firms. In 1994, American Express spun out Lehman Brothers Holding, Inc. in an IPO. Chairman and CEO Richard Fuld Jr. would be its final leader.

In 1997, Lehman made moves into mortgage origination. It bought BNC Mortgage, a subprime lender, in 2004 to join earlier acquisition Aurora Loan Services. Subprime lending, in theory, allowed people with less substantial credit to secure loans to buy a home. By 2003, Lehman ranked third in such loans. By 2006, BNC and Aurora were lending an astonishing $50 billion a month. By 2008, Lehman’s assets were valued at $680 billion; however, it only had $22.5 billion in firm capital. These were dangerous waters, as market fluctuations could put their entire structure in jeopardy.

Things began to take a negative turn in 2007 as the subprime mortgage crisis began in earnest. Lehman closed BNC, a move that cut 1,200 jobs. At the news of BNC’s closure, Lehman’s stock initially fell only 34 cents. By mid-2008, the company was in much deeper trouble. As reported in The New York Times on August 22, 2008, Lehman’s loss by the second fiscal quarter was $2.8 billion. “What happened was that home delinquencies in the subprime market rose dramatically and spread to the rest of the U.S. housing market,” says Robert Johnson, professor of finance from the Heider College of Business at Creighton University. “The mortgage-backed securities Lehman held in its portfolio fell dramatically in value, and the firm became insolvent and was forced to declare bankruptcy when no willing suitors could be identified.”

Lehman stock dropped 45 percent on September 9 when a proposed takeover by a Korean bank fell through. On September 10, Lehman announced a loss of $3.9 billion; stock dropped 7 percent as it announced further cutbacks in services. One day later, the stock dropped another 42 percent.

In 1997, Lehman made moves in mortgage origination. By 2006, [its subsidiaries] were lending an astonishing $50 billion a month.

Other forces came into play. Bank of America and Barclay’s emerged as potential buyers, but both passed. By September 15, what had once seemed impossible became inevitable. Lehman Brothers filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

The collapse shook the world economy and led to the U.S. government intervening in the form of the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008, which created the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) that allocated $700 billion (capped at $475 billion in 2010 by the Dodd-Frank Act) to buy toxic assets and bolster the financial system.

If we have learned anything, it’s that failures of big banks ripple across the world and cause the greatest damage to ordinary citizens who lose jobs, homes, and security.

How much at risk are we of another recession today, just over 10 years removed from the nadir of the Great Recession? Financial observers are wary. Yes, the Dow hit some highs this fall, but a precipitous drop just before Thanksgiving wiped out the year’s gains. Some experts also point to the fact that today’s long-term bond rates have dipped almost as low as short-term bond rates — a warning sign of an impending economic downturn.

As the saying goes, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.”

This article is featured in the January/February 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.