The Curious, Campy Success of Batman

The year was 1966, and television was starting to take itself less seriously. Programs like The Man From U.N.C.L.E. and The Wild Wild West were lightly satirizing action shows by introducing outlandish plots, ridiculous villains, and impossible gadgets.

No show took the concept of self-parody farther than Batman, which premiered in 1966. It purposely exaggerated every cliché of the detective story. Yet, as John Skow pointed out in his May 1966 Post article, it was among the most popular programs of its day. So popular that, when ABC interrupted an episode to report on the emergency return of the Gemini 8 space mission, the network was flooded with protests from outraged fans.

Batman quickly became more than just entertainment. It became the country’s biggest fad. References to the show popped up in conversation and worked their way into late-night talk shows. Everyone seemed to be enjoying this jokey version of a comic book hero. Sales of Batman merchandise in 1966 exceeded $75 million—about 60 percent more than James Bond merchandise had earned in any year.

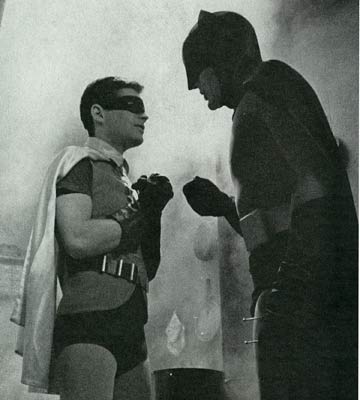

Unlike the action hero Bond, Batman was purely a comic hero: a parody of every good guy on TV. He was improbably strong, brave, and virtuous to the point of being preachy, as in this typical exchange with a villain:

RIDDLER: “With you two out of the way, nothing stands between me and the Lost Treasure of the Incas … and it’s worth millions!! Hear me, Batman, millions!”

BATMAN: “Just remember, Riddler, you can’t buy friends with money.”

No laugh track accompanied such lines, but viewers quickly lost any doubt they were watching a comedy.

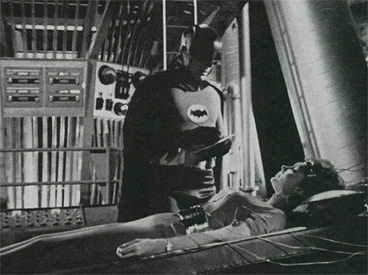

The look of the show—low-budget sets painted with comic-book colors—was heavily influenced by the Pop art craze. Starting in 1962, Pop artists used images from popular entertainment and advertising to ironically reflect American culture. (Remember Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s soup can?) The show’s chief writer, Lorenzo Semple Jr., chose a Pop art style as his protest against conventional TV programming. Serious dramatic shows, he said, relied on semi-truths and evasion. “We started out to do a Pop-art thing and we’re doing it.”

The mocking of the superhero figure also reflected the rise of “camp” humor. Camp emphasized the cheap, gaudy, and sentimental elements of popular culture. It was never meant to ridicule. The purpose was to ‘make fun with’ not ‘make fun of’ popular icons. (However, Skow believed camp humor was “mean spirited … a jeering private laugh at anyone square enough to take the pretension seriously.”)

Another influence on Batman the TV show was the public reaction in the 1950s against violence in comic books. Responding to pressure from parents and educators, publishers established the Comics Code Authority, which prohibited any references to brutality and gore.

The show took the new comic code even farther by eliminating any hint of violence. Batman was no more dangerous than a pillow fight with very small pillows. The crimes, committed by a gallery of returning characters, would involve stealing something, or taking over Gotham City’s government (in order to steal something). No one was ever murdered on the show. There was nothing more brutal than “comic violence”—burlesqued fistfights in which the words “Pow,” “Bam,” and “Zap” appeared in large, comic-font letters. And Batman always triumphed in the end.

For a while, this satire on a popular comic book hero was a successful formula. By 1968, however, the novelty had worn off and the last show aired 45 years ago this week.

It wasn’t a bad run. The show had been an audacious gamble with viewers’ indulgence. It had assumed, as Skow expressed it, “there was nothing that could make the adult American television watcher feel silly.”

The year that Batman disappeared for the last time into his papier-mâché Batcave, a new crime-fighter rose to the top of the TV rating: the tough, dedicated, but always cool hip Steve McGarrett of Hawaii Five-O.

Batman, of course, didn’t disappear. The comic books are still in print, though they are less restrained in their use of death and violence. The movie versions have become increasingly morose. The most current version, starring Christian Bale, who may be returning in a Justice League movie, is a grim, solitary loner. The caped crusader of the 1960s would barely recognize himself today.