How the Kellogg Brothers Changed Breakfast

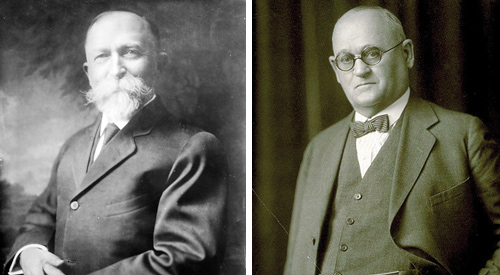

The popular singer and movie star Bing Crosby once crooned, “What’s more American than corn flakes?” Virtually every American is familiar with this iconic cereal, but few know the story of the two men from Battle Creek, Michigan, who created those famously crispy, golden flakes of corn back in 1895, revolutionizing the way America eats breakfast: John Harvey Kellogg and his younger brother Will Keith Kellogg.

Fewer still know that among the ingredients in the Kelloggs’ secret recipe were the teachings of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, a homegrown American faith that linked spiritual and physical health, and which played a major role in the Kellogg family’s life.

For half a century, Battle Creek was the Vatican of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. Its founders, the self-proclaimed prophetess Ellen White and her husband, James, made their home in the Michigan town starting in 1854, moving the church’s headquarters in 1904 to Takoma Park, outside of Washington, D.C. Eventually, Seventh-day Adventism grew into a major Christian denomination with churches, ministries, and members all around the world. One key component of the Whites’ sect was healthy living and a nutritious vegetable- and grain-based diet.

From the distance of more than a century and a half, it is fascinating to note how many of Ellen White’s religious experiences were connected to personal health. During the 1860s, inspired by visions and messages she claimed to receive from God, she developed a doctrine on hygiene, diet, and chastity enveloped within the teachings of Christ. She began promoting health as a major part of her ministry as early as June 6, 1863. At a Friday-evening Sabbath welcoming service in Otsego, Michigan, she described a 45-minute revelation on “the great subject of Health Reform,” which included advice on proper diet and hygiene. Her canon of health found greater clarity in a sermon that she delivered on Christmas Eve 1865 in Rochester, New York. White vividly described a vision from God which emphasized the importance of diet and lifestyle in helping worshippers stay well, prevent disease, and live a holy life. Good health relied on physical and sexual purity, White preached, and because the body was intertwined with the soul, her prescriptions would help eliminate evil, promote the greater good in human society, and please God.

The following spring, on May 20, 1866, Sister White formally presented her ideas to the 3,500 Adventists comprising the denomination’s governing body, or General Conference. When it came to diet, White’s theology found great import in Genesis 1:29: “And God said, ‘Behold, I have given you every herb bearing seed, which is upon the face of all the earth, and every tree, in which is the fruit of a tree yielding seed; to you it shall be for meat.’” White interpreted this verse strictly as God’s order to consume a grain and vegetarian diet.

She told her Seventh-day Adventist flock that they must abstain not only from eating meat but also from using tobacco or consuming coffee, tea, and, of course, alcohol. She warned against indulging in the excitatory influences of greasy, fried fare, spicy condiments, and pickled foods; against overeating; against using drugs of any kind; and against wearing binding corsets, wigs, and tight dresses. Such evils, she taught, led to the morally and physically destructive “self-vice” of masturbation and the less lonely vice of excessive sexual intercourse.

The Kellogg family moved to Battle Creek in 1856 primarily to be close to Ellen White and the Seventh-day Adventist Church. Impressed by young John Harvey Kellogg’s intellect, spirit, and drive, Ellen and James White groomed him for a key role in the Church. They hired John, then 12 or 13, as their publishing company’s “printer’s devil,” the now-forgotten name for an apprentice to printers and publishers in the days of typesetting by hand and cumbersome, noisy printing presses. Like many other American printer’s devils who went on to greatness — including Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Mark Twain, Walt Whitman, and Lyndon Johnson — Kellogg mixed up batches of ink, filled paste pots, retrieved individual letters of type to set, and proofread the not-always-finished printed copy. He was swimming in a river of words and took to it with glee, discovering his own talent for composing clear and balanced sentences filled with rich explanatory metaphors and allusions. By the time he was 16, Kellogg was editing and shaping the church’s monthly health advice magazine, The Health Reformer.

The Whites wanted a first-rate physician to run medical and health programs for their denomination, and they found him in John Harvey Kellogg. They sent the young man to the Michigan State Normal College in Ypsilanti, the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, and the Bellevue Hospital Medical College in New York. It was during medical school when a time-crunched John, who prepared his own meals on top of studying round the clock, first began to think about creating a nutritious, ready-to-eat cereal.

Upon returning to Battle Creek in 1876, with the encouragement and leadership of the Whites, the Battle Creek Sanitarium was born, and within a few years it became a world-famous medical center, grand hotel, and spa run by John and Will, eight years younger, who ran the business and human resources operations of the Sanitarium while the doctor tended to his growing flock of patients. The Kellogg brothers’ “San” was internationally known as a “university of health” that preached the Adventist gospel of disease prevention, sound digestion, and “wellness.” At its peak, it saw 12,000 to 15,000 new patients a year, treated the rich and famous, and became a health destination for the worried well and the truly ill.

There were practical factors, beyond those described in Ellen White’s ministry, that inspired John’s interest in dietary matters. In 1858, Walt Whitman described indigestion as “the great American evil.” A review of the mid-19th-century American diet on the “civilized” eastern seaboard, within the nation’s interior, and on the frontier explains why one of the most common medical complaints of the day was dyspepsia, the 19th-century catchall term for a medley of flatulence, constipation, diarrhea, heartburn, and upset stomach.

Breakfast was especially problematic. For much of the 19th century, many early-morning repasts included filling, starchy potatoes fried in the congealed fat from last night’s dinner. For protein, cooks fried up cured and heavily salted meats, such as ham or bacon. Some people ate a meatless breakfast, with mugs of cocoa, tea, or coffee, whole milk or heavy cream, and boiled rice, often flavored with syrup, milk, and sugar. Some ate brown bread, milk toast, and graham crackers to fill their bellies. Conscientious (and frequently exhausted) mothers awoke at the crack of dawn to stand over a hot, wood-burning stove for hours on end, cooking and stirring gruels or mush made of barley, cracked wheat, or oats.

It was no wonder Dr. Kellogg saw a need for a palatable, grain-based “health food” that was “easy on the digestion” and also easy to prepare. He hypothesized that the digestive process would be helped along if grains were precooked — essentially, predigested — before they entered the patient’s mouth. Dr. Kellogg baked his dough at extremely high heat to break down starch contained in the grain into the simple sugar dextrose. He called this baking process dextrinization. He and Will labored for years in a basement kitchen before coming up with dextrinized flaked cereals — first wheat flakes, and then the tastier corn flakes. They were easily digested foods meant for invalids with bad stomachs.

Today, most nutritionists, obesity experts, and physicians argue that the easy digestibility the Kelloggs worked so hard to achieve is not such a good thing. Eating processed cereals, it turns out, creates a spike in blood sugar, followed by an increase in insulin, the hormone that enables cells to use glucose. A few hours later, the insulin rush triggers a blood sugar “crash,” loss of energy, and a ravenous hunger for an early lunch. High-fiber cereals like oatmeal and other whole-grain preparations are digested more slowly. People who eat them report feeling fuller for longer periods of time and thus have far better appetite control than those who consume processed breakfast cereals.

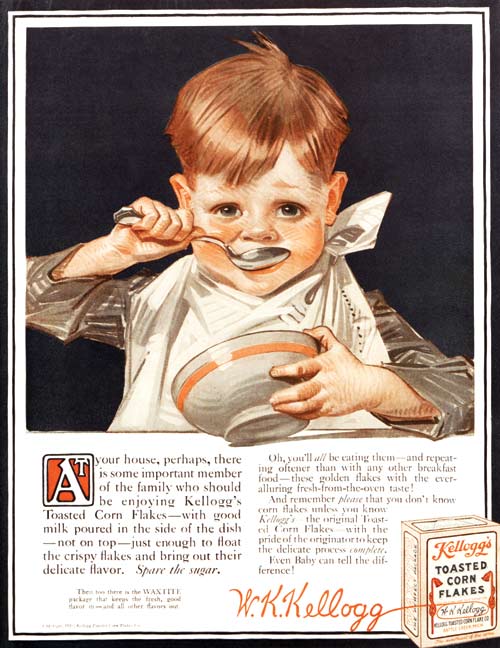

By 1906, Will had had enough of working for his domineering brother, whom he saw as a tyrant who refused to allow him the opportunity to grow their cereal business into the empire he knew it could become. He quit the San and founded what ultimately became the Kellogg’s Cereal Company based upon the brilliant observation that there were many more average people who wanted a nutritious and healthy breakfast than invalids — provided the cereal tasted good, which by that point it did, thanks to the addition of sugar and salt.

The Kelloggs had the science of corn flakes all wrong, but they still became breakfast heroes. Fueled by 19th-century American reliance on religious authority, they played a critical role in developing the crunchy-good breakfast many of us ate this morning.

Howard Markel is the George E. Wantz Distinguished Professor of the History of Medicine at the University of Michigan and author of The Kelloggs: The Battling Brothers of Battle Creek (Pantheon Books, 2017). This essay is part of What It Means to Be American, a partnership of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History and Zócalo Public Square. Originally published at Zócalo Public Square.

This article appears in the March/April 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.