6 Myths about the Stock Market Crash of 1929

The great stock market crash of October 29, 1929, was so unbelievable and so excessive that is inspired several enduring myths. Here are 6 commonly held beliefs about the great crash that turn out to be more legend than fact.

1. The Crash Came Out of Nowhere

One of those myths claims the Crash was totally unexpected. Admittedly, it was dramatic reversal of economic trends. America had experienced 30 years of continual economic growth. While some believed — or wanted to believe — that the stock market would continue to rise, business leaders knew a correction was coming. Sooner or later, the market would come to its senses and stock prices fall back down to reality.

Yet stocks continued to soar, nearly doubling in a year.

One factor that drove up prices was the easy credit that banks extended to investors. They could now buy on “margin,” which meant they paid only part of the stock price. Their banks provided the remaining amount. The difference (“margin”) would be repaid out of the stock’s anticipated earnings.

But if stock started losing money, the bank would sell the stock and the buyer have to repay the bank what they put up for the margin.

2. Everyone Invested in the Market

This leads to another legend: that a broad cross-section of Americans — farmers, school teachers, factory workers — invested in the market. Supposedly, nearly everyone was in the stock market prior to the crash. One historian asserted that as many as 20 million Americans were buying securities. But according to the Treasury Department’s calculations, the number was actually three million. And brokerage houses reported it was half that number by 1929, which means that over 97 percent of America watched the stock market crash from the sidelines, according to Freedom From Fear by David M. Kennedy.

3. The Stock Market Collapsed in One Day

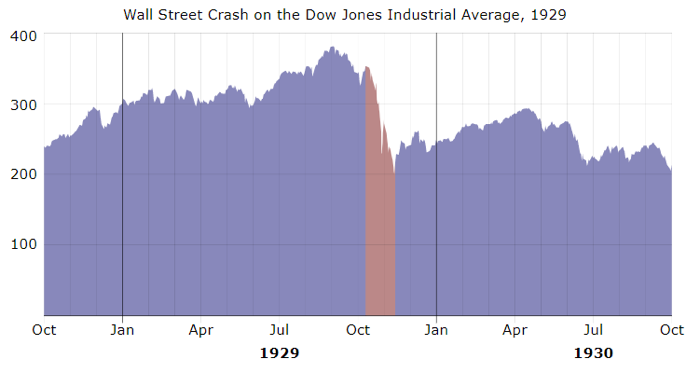

The first sign of trouble was a mysterious drop in prices in September, but it quickly reversed itself, again without reason. All was peaceful until October 23, when the market received a flood of sell orders. By the end of the day’s trading, six million shares had been sold, mostly at a loss. Four billion dollars in stock value was lost.

The slide continued on Black Thursday. Nearly 13 million shares were traded, and the loss in stock value amounted to $9 billion. Panicking investors took some encouragement by a surge of buying at the end of the day. By closing, market values had recovered about a third of what had been lost on Wednesday.

Business leaders urged investors to remain calm and ride out the storm. The market, they said, could still recover from this “correction.”

The market on Saturday’s half-day of trading showed no losses on the scale of the previous three days. But on Monday morning the slide returned. The price of a share might drop anywhere between two and ten points between sales.

And then came Black Tuesday.

The very first item reported on the ticker that morning was the price of Anaconda Copper. It had traded at 96 the day before. At 9:00 AM, it was already down to 80. Investors began frantically selling, driving down the price of stocks sharply.

Within the first half hour 3.2 million shares had been traded. AT&T fell from 310 to 204, RCA fell 110 to 26.

By noon, 8 million shares had been sold.

In the afternoon, prices seemed to level off. Anaconda was now selling for $10 a share. Bank stocks fell, too; National City Bank dropped from 450 to 320.

When trading ending, 30 leading industrial stocks had lost 40 percent of their September value.

According to William Klingaman’s 1929: The Year of the Great Crash, total losses since the previous Wednesday were $15 billion.

Traders who had been wiped out wandered aimlessly though hotel lobbies and down the streets crowded with 10,000 people, drawn to the Wall Street area by reports of the crash.

Harpo Marx, who’d sunk his fortune in Wall Street, received a telegram from his broker. “Send $10,000 in 24 hours or face financial ruin.” But Harpo was already ruined, having sent the last of his money to cover previous margin calls. He was left, he said, with only his harp and his croquet set.

Klingaman notes in his book that composer Irving Berlin admitted, “I was scared. I had had all the money I wanted for the rest of my life. Then all of a sudden, I didn’t. I had taken it easy and gone soft and wasn’t too certain I could get going again.”

The market continued to fall for the next three weeks.

4. Many Stockbrokers Jumped from Buildings

The most colorful legend of the Crash is that of the plummeting millionaires.

Winston Churchill was staying at the Savoy-Plaza Hotel in New York the day after Black Tuesday. That morning, he looked out his window at a crowd forming in the street, staring, he learned, at a man who’d thrown himself down fifteen stories. Somewhat flippantly, he said, “quite a number of persons seem to have overbalanced themselves by accident in the same sort of way.”

In fact, there were no reports of ruined businessmen hurling themselves from skyscrapers that day. Moreover, as economist John Kenneth Galbraith discovered, the suicide rate for October and November of 1929 actually dropped.

Klingaman notes that the crash did result in some fatalities, though, like the man watching the stock ticker in his broker’s office who dropped dead. Or the investor in Kansas City who shot himself in the chest. Before dying, he said, “Tell the boys I can’t pay them what I owe them.”

There are three reports of jumpers in New York city. One was a woman working in a brokerage who’d been processing sales figures to a point beyond exhaustion. She jumped from the 40 story Equitable Building on November 7. Nine days later, a member of the New York Mercantile Exchange leapt to his death. The third jumper was an executive for the Earl Radio Corporation who’d lost his fortune and was now $23,000 in debt — but this had occurred weeks before the crash.

5. The Stock Market Crash Started the Great Depression

It seems to make sense; Wall Street fortunes are wiped out and the economy falls into a long decline. Yet economists can find no direct connection between the Great Crash and the Great Slump. A business slowdown had been noted in the summer of 1929, but it was nothing extraordinary. Even after reports of the Crash circulated, American business seemed unaffected. The day after Black Thursday, President Herbert Hoover made a statement that would haunt him for the rest of his days: “the fundamental business of the country, that is production and distribution of commodities, is on a sound and prosperous basis.” However, according to Kennedy’s Freedom From Fear, it was probably an accurate description of the American economy at that moment.

6. The Government Just Sat Back and Watched the Market Fall

Lost amid all the tragic legends of the Crash is the story of a nearly forgotten hero. George L. Harrison, governor of the New York Federal Reserve Bank, made a proposal to several of the bank’s board members. Consequently, he announced, before trading began on Tuesday, October 30, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York would purchase $100 million in government securities, according to Maury Klein in Rainbow’s End: The Crash of 1929.

The purchase brought badly needed money into the market. It was, according to business historian Maury Klein, “the pivotal moment of the crash. By making these funds available to banks for lending during the severe credit crunch, he probably saved many individuals and institutions from failing. No single act did more to stave off even worse disaster on this disastrous day.”

Featured image: Alamy