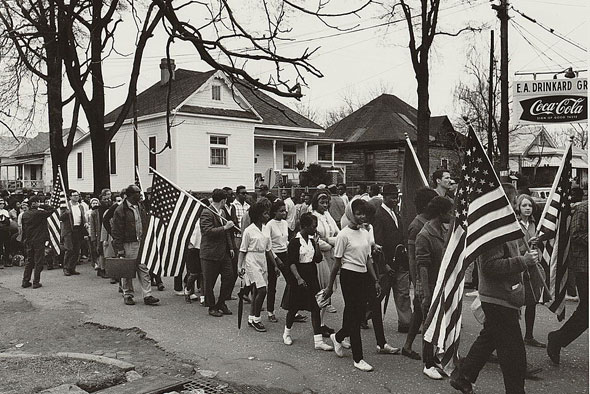

Selma and the Fight to Vote

(Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Last year marked a new low for voter participation in a national election. Normally, less than half of America’s voters cast ballots in the midterm elections, but the 2014 turnout was the lowest in 73 years: 36 percent. It would seem that most Americans believe their right to vote isn’t worth the effort to exercise it.

We’ve come a long way in 50 years, when Americans were ready to die just to get their names on the voter rolls — and others were willing to kill to deny them that right.

In the early 1960s, civil rights advocates traveled through the Southern states to encourage African Americans to vote. They believed the ballot would give people the power to throw out racist government officials and elect leaders who would end discrimination.

But they soon discovered that office-holders across the country had installed a number of obstacles to prevent black people from reaching the polling booths. The obstacles proved especially effective in Selma, Alabama, where only 2 percent of black residents were registered to vote.

In March 1965, activists announced they would march from Selma to Montgomery, the state capitol, and demand the state government end voter suppression. They had little hope that Governor George Wallace would change the state’s racist policy, but they knew the national attention from the march would pressure him to respond.

When marchers sets off on Sunday, March 7, the country saw how firmly some white officials opposed voting rights for black people. Sheriff’s deputies fired tear gas into the crowd, then attacked the marchers with whips and clubs. Fifty marchers were hospitalized. The marchers set out again on March 21, led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and with protection from the National Guard and U.S. Army sent by President Johnson.

On the second day, the marchers passed through Trickem Fork, an impoverished hamlet in Lowndes County, Alabama, that represented much of what the protestors were trying to change. The Saturday Evening Post reporters W. C. Heinz and Bard Lindeman noted, “The Negroes outnumber the whites almost four to one, but until the week before the Freedom March not one Negro voter had been registered in Lowndes County in 65 years.” (“The Meaning of the Selma March: Great Day at Trickem Fork,” May 22, 1965)

Several residents had recently tried to register at the county office. White officials turned them back, saying one of their registrars was sick and they didn’t know where the other one was. Two weeks later, when the residents returned, county officials told them to register at the old jailhouse. One of the residents said, “They had the two tables set up in this room with the gallows on the left. While you’re filling out the paper, one white man is saying. ‘I guess many a guy dropped through there.’ Then another is saying, ‘I wonder if the old thing still works.’”

Another resident, an Army veteran, was told he needed to pass a literacy test. “They gave me hard questions. The first was: ‘What part does the Vice President play in the Senate and the House?’ The second was: ‘What legal and legislative steps would the State of Alabama and the State of Mississippi have to take to combine into one state?’”

Literacy tests were the last resort for state officials who wanted to deny African Americans their right to vote. Ever since Reconstruction ended in the 1870s and federal troops left the South, many white politicians sought to limit black people’s voting. In Mississippi, black voters’ names were removed from the registration polls, then required them to pay poll taxes for two years before they’d be allowed to cast ballots.

African Americans who still expressed an intention to vote might be threatened with losing their jobs. And some cities distributed fliers telling black voters they could not enter a polling station if they’d had any trouble with the law — even something as trivial as a parking ticket — unless they first got approval from their local sheriff.

(Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Black voters were denied credit, threatened with eviction or even lynching. If nothing else stopped these voters, there was always the literacy test. White county clerks were allowed to refuse to register anyone they considered “illiterate.”

They might require black registrants to read, and explain, complex passages of state law.* In Alabama, they would ask prospective voters questions about Federal law, as in these examples:

Has the following part of the U.S. Constitution been changed? “Representatives shall be apportioned among the several states according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each states, excluding Indians not taxed. (No)

Who pays members of Congress for their services, their home states or the United States? (United States)

At what time of day on January 20 each four years does the term of the president of the United States end? (12 noon)

If a bill is passed by Congress and the President refuses to sign it and does not send it back to Congress in session within the specified period of time, is the bill defeated or does it become law? (It becomes law unless Congress adjourns before the expiration of 10 days.)

The literacy-test questions in Louisiana were more like brain-teasers problems, deliberately phrased to confuse the prospective voters.

In the space below, write the word “noise” backwards and place a dot over what would be its second letter should it have been written forward.

Draw in the space below, a square with a triangle in it, and within that same triangle draw a circle with a black dot in it.

Spell backwards, forwards.

Draw a figure that is square in shape. Divide it in half by drawing a straight line from its northeast corner to its southwest corner, and then divide it once more by drawing a broken line from the middle of its western side to the middle of its eastern side.

Divide a vertical line in two equal parts by bisecting it with a curved horizontal line that is only straight at its spot bisection of the vertical.

As questions on a cocktail napkin, they might have been amusing. But black citizens were required to answer 30 of these questions in 10 minutes without mistakes before they could register to vote.

The insolence of racist government policies may seem extraordinary to us today. Even more extraordinary was the determination of African Americans to overcome these challenges. They were helped in some areas by civil rights activists like members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, who taught them how to beat the trick questions. But these efforts couldn’t have succeeded if the men and women in places like Trickem Fork weren’t determined to overcome the challenges that lay between them and their right to vote.

So it seems surprising that, within the lifetime of the baby boom generation, the right to vote has become so little valued that almost 50 percent of Americans never vote in any major election.