Considering History: Blackface’s Inescapable Stain on American Culture

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Incidents and images of blackface have dominated the last week’s news cycle. As of this writing at least three prominent Virginia political leaders (the governor, attorney general, and Senate majority leader) have all been tied to the racist practice, as has Mississippi’s lieutenant governor. While those incidents were all in the politicians’ pasts, another shocking scandal reflects blackface’s continued cultural presence, as Gucci was discovered to be marketing a wool sweater clearly intended to echo the most caricatured, extreme blackface images (making it the latest in a series of high-end companies attempting literally to capitalize on blackface in the 21st century).

These incidents have been rightly condemned, and both the politicians and corporations are likely to face significant and deserved consequences for their links to blackface. But it’s vitally important that we not assume blackface is simply a reflection of overt racists or a few bad apples. The racist practice is deeply embedded in American history and culture, and recognizing its sweeping legacies allows us to better understand the presence of bigoted imagery in many of our foundational social systems and cultural forms.

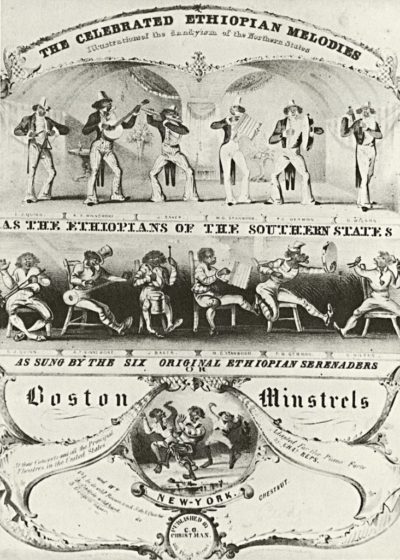

Blackface minstrelsy is one of the oldest American cultural forms. As scholar Eric Lott traces in his magisterial Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class (1993), the early 19th century development of minstrel shows represented a strikingly unique American innovation on longstanding theatrical genres like comedy and the burlesque. Most of the era’s most prominent stage actors, from Edwin Forrest to George Washington Dixon, specialized in performing as blackface characters like the ubiquitous “Sambo,” building both their individual reputations and American theater’s exploding popularity around these caricatured characters.

In 1828, New York comic performer Thomas Dartmouth (T.D.) Rice (known professionally as “Daddy Rice”) debuted a new such blackface character, Jim Crow, in the song-and-dance number “Jump Jim Crow.” The act became such a national (and eventually even international) sensation that a decade later the Boston Post would write, “the two most popular characters in the world at the present time are [Queen] Victoria and Jim Crow.” Ironically but tellingly, Rice’s humorous fictional character would become a focal image through which white supremacists could mock, stereotype, and oppress African Americans, as exemplified by the direct association of “Jim Crow” with the rise of segregationist and racist laws and social practices throughout the post-Civil War South.

Compared to that direct link between a minstrel character and an entire legal and social system, blackface’s effects on late 19th and 20th century American popular culture were more subtle but just as sweeping. As American theater separated from European traditions and developed its own identity across the 19th century, the most popular and consistently present theatrical works were the Tom Shows, stage productions based on Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1851). Even before the Civil War, those shows began to transform from abolitionist critiques of slavery (ones based directly on Stowe’s novel) into blackface burlesques. After the war, blackface minstrelsy became the Tom Shows’ dominant mode, and would remain so well into the 20th century. The shows gradually came to feature African American performers in the background (often singing “plantation melodies”), but it was white actors in blackface who embodied such famous, caricatured figures as Tom and Topsy.

Along with the Tom Shows, another central theatrical trend in turn-of-the-century America were vaudeville shows. These variety shows provided a hugely popular bridge between the theater and the 20th century’s most dominant pop culture forms, including radio, films, and television; indeed, some of the century’s most enduring pop culture figures, such as George Burns, moved directly from vaudeville into those other media. Vaudeville shows usually featured ten or more distinct performers and acts in a variety of styles, but blackface performances were a constant and central presence, often opening and closing the shows as guaranteed crowd pleasers. And virtually all of the most famous vaudeville stars, from Jack Benny to Milton Berle to Laurel and Hardy to George Burns himself, incorporated blackface into their acts.

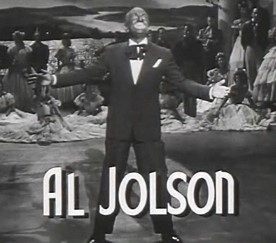

As vaudeville gradually gave way to the motion picture industry, that 20th century cultural form likewise depended heavily on blackface performances. The first blockbuster silent film, director D.W. Griffith’s controversial mega-hit The Birth of a Nation (1915), featured white actors in blackface in many of its crucial villainous roles. Well before Birth, some of the earliest popular silent films were blackface (or “coon”) comedies like The Wooing and Wedding of a Coon (1907), The Pickaninnies (1908), and The Sambo Series (1909-11). And perhaps most strikingly, the first prominent “talkie” film, 1927’s The Jazz Singer, features Al Jolson as an entertainer who spends much of the film (including its triumphant finale) in blackface, cementing the central role of blackface to the evolution of American film across each of its foundational periods.

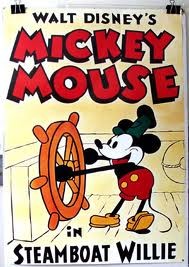

Just a year after Jolson sang his way into history, the Disney Animation Studios character Mickey Mouse made his debut, in 1928’s Steamboat Willie. As historian Nicholas Sammond traces at length in Birth of an Industry: Blackface Minstrelsy and the Rise of American Animation (2015), foundational animated characters like Mickey (as well as Felix the Cat and Bugs Bunny, among many others) were directly inspired by blackface minstrelsy and vaudeville tropes and images. Mickey’s minstrel influences are particularly clear in such early animations, from his top hat, cane, and white gloves to his exaggerated whistling, dancing, and slapstick humor. And indeed, in 1933 Disney Animation released the short film Mickey’s Mellerdrammer (a caricatured dialect misspelling of “melodrama”) in which Mickey and friends perform their own version of a Tom Show while in blackface.

Yes, even Mickey and Disney are inextricably intertwined with blackface. Those century-old cultural interconnections and influences meant that blackface performance was widely accepted throughout much of the 20th century, as illustrated by the 1986 teen comedy film Soul Man, in which C. Thomas Howell’s protagonist Mark Watson spends most of the film using blackface to disguise himself as an African American man and benefit from an affirmative action law school admissions program. While the NAACP and other activists challenged blackface’s stereotypes and bigotry throughout those eras, it was only with controversies such as that surrounding Ted Danson in 1993 that widespread cultural critiques of blackface performance emerged. And even as recently as 2015, a Yale administrator emailed students to argue that they should ignore an official request to stay away from blackface in Halloween costumes, reflecting the continued debate into our own moment over this pernicious but longstanding and widespread form of racial performance.

Yes, even Mickey and Disney are inextricably intertwined with blackface. Those century-old cultural interconnections and influences meant that blackface performance was widely accepted throughout much of the 20th century, as illustrated by the 1986 teen comedy film Soul Man, in which C. Thomas Howell’s protagonist Mark Watson spends most of the film using blackface to disguise himself as an African American man and benefit from an affirmative action law school admissions program. While the NAACP and other activists challenged blackface’s stereotypes and bigotry throughout those eras, it was only with controversies such as that surrounding Ted Danson in 1993 that widespread cultural critiques of blackface performance emerged. And even as recently as 2015, a Yale administrator emailed students to argue that they should ignore an official request to stay away from blackface in Halloween costumes, reflecting the continued debate into our own moment over this pernicious but longstanding and widespread form of racial performance.

Blackface’s presence doesn’t mean we have to cancel much of American popular culture—but it does mean that we have to better remember and engage with these widespread, inescapable legacies of blackface minstrelsy across our cultural and social landscapes. Perhaps this moment of heightened attention to the histories of blackface can help us start that long overdue collective reckoning.