Hoops, Bloomers, and Common Sense

In times past when newspaper editors had to fill space on their editorial pages they could always turn out a few hundred words on “safe” topics like the weather, the need for government reform, motherhood, or the flag. And—for many years—the latest fashion.

Any self-respecting publication would regularly critique the latest dress styles with heavy-handed ridicule and indignation about the decadent new styles. (“What, we ask, is this country coming to?”)

What brought this topic to mind was the anniversary of the Women’s Rights Convention, which opened in Seneca Falls, New York, on July 19th, 1848. The conference might have been completely ignored by the press had it not been for Elizabeth Smith Miller, who appeared in public wearing the first Bloomer skirt. (The name was only attached later, when they were championed by Amelia Bloomer, editor of a suffragist newspaper.)

Borrowing from Middle Eastern clothing, the outfit featured long, loose trousers that gathered at the ankle, which were worn beneath a knee-length skirt.

Naturally they provoked a storm of criticism. The press had endless fun ridiculing the fashion, which they saw as new, unattractive, and faintly masculine. Trousers had been an exclusively masculine trait in western fashion as long as anyone could remember. Any woman who wanted to cover her legs separately was obviously trying to encroach on male privilege.

The Bloomer skirt never caught on (in fact, pants for women remained an oddity until the 1940s), but they didn’t fail to gain acceptance because of the ridicule of male editors and pundits.

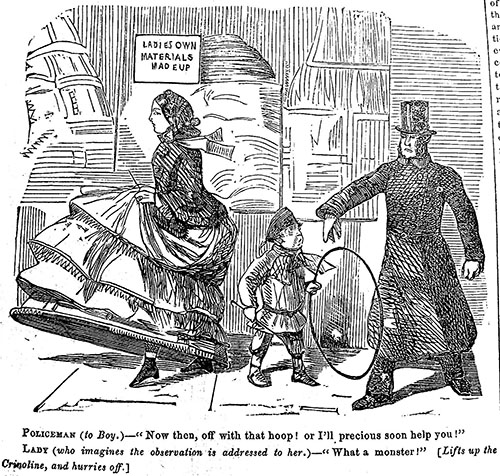

One of the biggest reasons that the Bloomer skirt went bust was its great dissimilarity with the height of high fashion at the time, the voluminous crinoline hoop-skirt. This contraption of whalebone or cane held a dome of crinoline over a network of hoops that often reached 6 feet in diameter. The skirt was tricky to maneuver; women had to learn how to pass through doorways or simply sit down without tipping up the skirt on its side.

What made the hoop skirt so impractical wasn’t its unpredictable movement but the tight bodice that was part of the outfit. While the legs enjoyed greater freedom within the skirt, the required corset crushed the wearer’s lungs in a vise of heavy cotton reinforced by bone or steel. “Why do people wear such things?” a Post writer wondered in 1856.

Is it because they think them beautiful, elegant, tasteful, or because they find them comfortable, useful, convenient? Not at all. Because they are in the fashion. A common custom makes cowards of us all. If the Parisian arbiter of fashions should decree a garb of plate-mail, we would hasten to put it on.

Although the author has no appreciation of the Bloomer skirt, he at least concedes a few points in its favor.

The advantages of a hoop skirt.Well, it certainly is ugly. But if it had come from Paris, it would never have been laughed off the forms of our venturous ladies. The subtle French would have persuaded us it was the most beautiful thing ever invented. Fortunately, or unfortunately, it came from the mind of an American woman, benevolently moved to lighten the weight of skirts which afflict so many females with incurable diseases, and impede and discomfort so many; and as she had no spell of foppery to weave over the common-sense of the country, of course she failed ignominiously. Ugly?—so it is; but did it fail for that reason? Is it any uglier than these frightful hooped skirts, which transform the graceful figures of our belles in to the semblance of diving-bells? [“The Philosophy of Dress,” October 25, 1856]

An English writer offered two more reasons the Bloomer skirt never caught on.

It was doomed to failure, even without a fair trial, for two reasons. In the first place, it only met the difficulty halfway. It was a compromise between the dress we now wear and that of the ladies of the East. The large trousers were adopted, but the tight-fitting body and corset were allowed to remain, and thus the most important point in the necessary change neglected.

Another reason, and which, perhaps, operated more powerfully in causing the rejection of the Bloomer costume, lies in the perception that most of the actions of the American ladies are unfeminine.

English women have a natural horror of being thought masculine, or strong-minded, in the extreme sense of the word. Had the reform commenced in any other quarter, there is little doubt it would have been carried out with success. As it was, no one could disconnect [the Bloomer skirt from] the idea of the “Female Rights Association,” or some such movement, and hence the utter hopelessness of it being adopted. [“Suggestions on Female Dress,” December 12, 1863]

Lastly, there was the marketing problem of placement. Put simply, the wrong people were wearing Bloomer skirts.

When women proposed to wear a truly sensible and beautiful dress, men opposed it, not only by argument, but by brute force. The Bloomer is the costume to which I refer. Of course, when I mention it, men will have in their minds a picture of the Bloomer as they have seen her. They must try to remember, if the superiority of their minds will allow them, that the Bloomer has been worn only by old and ugly women, who exhibited the most hideous taste in its combinations. Let the young and lovely have a chance at it for a month or so, and I would like to see where male logic would be at the end of it. [“A Lady’s Ideas on Crinoline and Bloomers,” April 19, 1862.]

The shapes, fabrics, and colors of women’s wear have changed enormously since the Civil War era. And although it can be debated whether modern style is more attractive or sensible than it was 150 years ago, no one would argue with this one fact: Women’s clothing has become a lot more comfortable—with the exception of high heels.