Part I: Health Insurance in 1958

Today we are still arguing over who’s responsible for the high cost of healthcare. Get the facts on health insurance in this investigative three-part series from 1958.

[See also: “Fixing Our Healthcare System” from our Sep/Oct 2012 issue.]

The Post Reports on Health insurance

Part II: The High Cost of Chiseling

Part III: Is This The Pattern of the Future?

June 7, 1958—Hospitals overcharge insured patients; doctors pad fees; patients demand unnecessary treatment. These are the whispered accusations.

Here are the facts.

In insurance circles, particular honor has long been accorded a group of statisticians known as the crystal-ball boys. With startling accuracy, these experts can predict almost everything from how many appendicitis victims will perish next August to how many children will be born with blue eyes or cleft palates.

“We can usually present such prediction with great confidence,” says one of these men. “But occasionally we have made mistakes, and some of these have been lulus.”

Perhaps the most embarrassing of all these erroneous predictions in recent years was one, which involved the insurance business itself. This was the general failure to foresee the future of health insurance. Originally, health insurance was aimed at protecting the public against the financial shock of sudden severe illness. Also, and by no means incidentally, it was intended to halt state medicine. It was of barely modest size in the 1930s and early 1940s, and most experts predicted it would remain that way or grow only slowly. This turned out to be about as unsound as predicting that Jayne Mansfield would always be flat-chested.

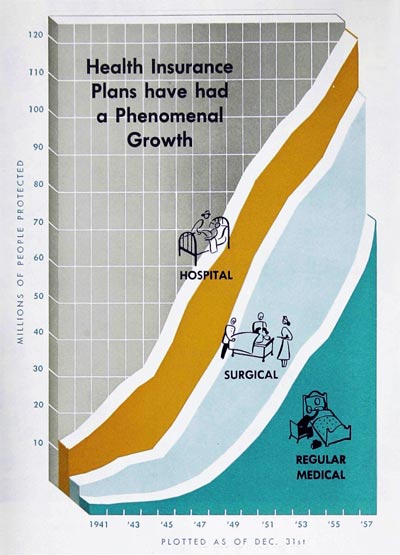

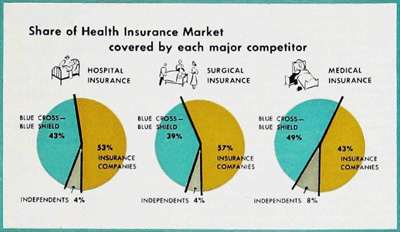

During the last ten years, health insurance not merely grew but practically exploded into a multi-billion-dollar giant ranking with the major businesses of the country. This year, according to the best available estimates, health insurance may finally surpass life insurance in the number of people covered. By the start of 1958, there were roughly 123 million Americans—more than 70 percent of the population—with some form of hospital insurance; 109 million with some form of surgical insurance; and 74 million with some form of nonsurgical medical insurance. Last year, health insurance covered a whopping $4.2 billion, or about one-fourth of our personal-sickness bill for the year.

With the exception of television, or of bootlegging during prohibition days, probably no other peacetime industry has grown so big so fast. On this there is wide agreement among authorities of Blue Cross, Blue Shield, commercial health-insurance companies, medical societies, hospital associations, labor unions, and employer groups.

Among these same authorities, however, there is no complete agreement on what the public wants and is willing to pay for, nor on even such basic points as how many people may practically be covered, what kind of policies they should have, how their health-insurance protection should be delivered, and who should pay how much to whom for what.

Equally important, serious and dangerous internal disputes, which were mainly kept hidden from the public, have recently broken out in a nationwide rash of noisy attacks, disclosures, and denunciations. During the past few months, for instance, patients in some areas were being accused of putting pressure on doctors with demands for luxury treatments, needless diagnostic surveys or “dragnets,” or a few extra days in the hospital, merely on the grounds that they could be covered by their insurance policies.

“We simply can’t turn these people down,” one physician confessed at a Chicago meeting. “Sure, I know this is boosting the cost of medical care. But if I don’t give them what they want, even though I know it’s not justified, they’ll just go to another doctor and he’ll collect the fee.”

At the same time, a few doctors themselves were being attacked by patients, by insurance organizations, and even by their brother doctors for soaking insured patients with big bills, primarily because these patients had insurance. Medical societies, headed by the American Medical Association, were being berated by labor and Government officials for steadfastly opposing what these officials termed “any improvements” in existing health-insurance plans. Insurance companies were being charged with refusing to pay legitimate bills, capriciously canceling individual policies without adequate cause, and terminating protection on most patients when they became old or ill and desperately needed protection. Some of these companies were assailed by the Federal Trade Commission for misrepresentation in their advertising, and a few were under fire for marketing the low-cost “bargain” insurance known in some quarters as a Fourth of July policy.

“This,” explains an insurance expert, “is a policy which sounds good, but is so limited that it will provide coverage for only the most rare events-like being trampled by a bull elephant on Main Street at high noon on the Fourth of July.”

Probably the most heated battles were raging over the deeds or misdeeds of hospitals and their allied hospital insurance system, Blue Cross. Some months ago, for example, investigators set off one sizzling row when they found a Tennessee hospital that was serving as a virtual baby sitter for parents with health insurance.

“It’s really wonderful, and so easy,” one Tennessee woman naïvely admitted. “When my husband and I want to go up to Washington for the weekend, we don’t have to hire us a sitter. We just take the baby to the hospital and say we think it’s got measles or something. They keep the baby for us until we get home. We sign the insurance forms, and it really doesn’t cost anybody anything.”

In one Midwestern state, a medical society survey revealed that more than 30 percent of the patients in typical hospitals were spending a staggering number of needless days in a hospital bed. The cost of that abuse was estimated to be nearly $5 million a year in one state alone.

“Every insured patient who occupies a bed while he has a wart or mole removed, or while he has some simple laboratory or X-ray tests performed,” the investigating doctors claimed, “contributes to the rising cost of hospital operation and the increasing cost of health insurance.”

Similar accusations have been brought in Massachusetts, Ohio, Illinois, Minnesota, Colorado, and California. In New York, it was claimed, hospitals were discriminating against insurance companies or uninsured patients in favor of Blue Cross by giving the latter a 15 percent discount in what was described as an undercover kickback. In Philadelphia, where one of the most vigorous disputes was raging, Dr. Samuel Hadden, president of the local county medical society, blasted hospitals for striving to keep all there beds occupied and letting Blue Cross pay the bill.

“When Blue Cross assumes the obligation to hospitals to keep their beds filled,” he said, “it is running up the costs of illness unnecessarily and is betraying the public.”

Even labor and management, through their mishandling of jointly administered health and welfare funds, have been denounced for costly abuses. Several East Coast probes have revealed that money provided by workers and employers to pay health-insurance premiums was being used to finance strikes, bribe officials, and supply welfare-funded officials with high-priced cars, country-club memberships, and luxurious vacations in Miami, Las Vegas, and Palm Springs.

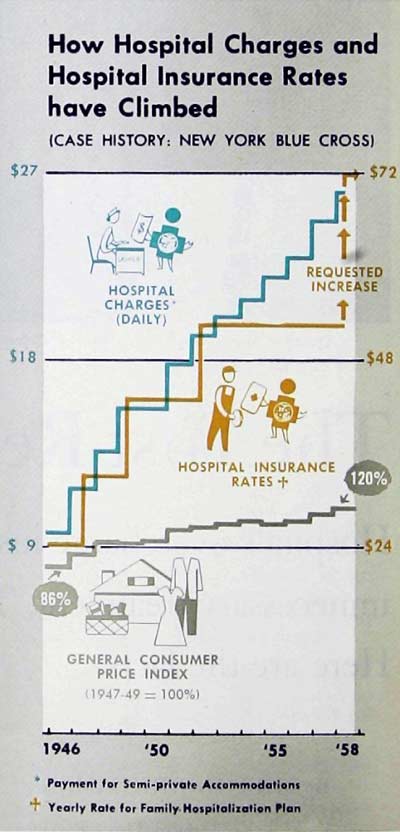

Partly as a result of all these abuses and shenanigans, as well as because of increases in salaries, drug costs, and the like, the price of health insurance is now rising sharply in some areas. Blue Cross, for example, has recently requested rate increases of 23 percent in Michigan, 40 percent in New York, and 42 to 71 percent in Philadelphia, and has already instituted generally similar increases in Southern California.

These increases, it has been asserted, are threatening to price health insurance out of the market, making it too expensive to be purchased by those Americans who need it most urgently. To thoughtful leaders in almost every field involved, this prospect is frightening.

“This could become a strange and dangerous situation,” says Dr. William Shepard, a vice president of Metropolitan Life, former president of the American Public Health Association, and one of the most highly respected authorities on the economics of medical care.

“Voluntary health insurance,” he notes, “was created in large part to prevent compulsory, Government-controlled health insurance. We all co-operated to make it grow. It has grown rapidly—perhaps too rapidly. Now it is in great peril. If it collapses, it will inevitably bring the one thing it was supposed to prevent—Government control of the practice of medicine.”