‘My Pink Ribbon’

Illustration by Hadley Hooper.

October is Breast Cancer Awareness Month. It’s a time when it seems you hear about breast cancer everywhere you turn. Pro football teams play their October games wearing pink shoelaces and cleats, chin straps, wristbands, and helmet decals. Even the game balls have pink ribbon decals.

The public relations campaign to get us thinking about breast cancer has been quite effective. But with all the attention to the issue, most are still not aware that men can, and do, get breast cancer. I say this from first-hand experience. In June 2010, after a seven-mile run near my home in Anderson, Indiana, I noticed a swelling in my left breast, and, when I massaged it, I felt a palpable lump.

I didn’t think much of it at the time, but I was concerned enough to have it checked by a surgeon I’d seen a year before for a minor procedure. When I arrived at his office two weeks later, I showed him the swelling and he did a fine needle aspiration (biopsy) of the lump right on the spot.

An hour later, the report came back. I’d tested positive for breast cancer. I was still in his office, stunned, as he informed me, “For men, there’s really only one option—a complete mastectomy.”

Feeling numb, I said “OK” and scheduled the surgery for four days later. Then I had to go home and tell my wife, Elise, whom I had not told about the lump or the doctor’s visit because I hadn’t wanted her to worry.

At the appointed time, the surgeon removed my entire left breast. He also took four lymph nodes. Afterward he biopsied the nodes to see if the cancer had spread. The test came back positive for one of the nodes. Not a good sign. The surgeon told me that because he’d found cancer in that first node, it was very likely that the cancer had traveled elsewhere in my body.

Up until then, stunned though I was, I hadn’t worried too much. Now, it was different. I started thinking about dying. I began reading everything I could about breast cancer. One of the first stories I found online was about a 28-year-old British man who died after a four-year battle with breast cancer. And here I was, in my 60s. But, I reminded myself, I was quite healthy. I have been a runner all my adult life. I’d quit smoking 18 years earlier. I rarely drank alcohol.

I ate nutritious foods almost all the time. Plus, there was no history of breast cancer in my long-lived family, which included two older sisters and my 92-year-old mother never had cancer.

I returned to the hospital for surgery two weeks later, this time to remove nine more lymph nodes. About a week later, I went with Elise to the doctor’s office to learn the biopsy results. I felt very nervous as we awaited the verdict.

Amazingly, all nine lymph nodes tested negative. Elise and I both found ourselves weeping tears of joy. It was like having a death sentence commuted.

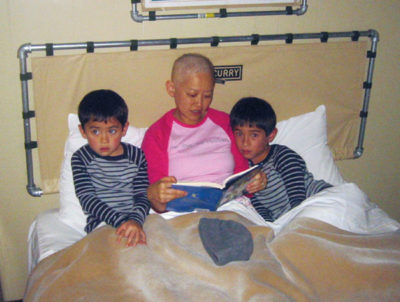

The follow-up treatment wasn’t so terribly bad, all things considered. I made it through 49 chemotherapy and radiation treatments over the next eight months. Throughout that period, I never experienced fatigue, nausea, or missed a day of work. My oncologist told me I was lucky; only about 10 percent of his patients breeze through treatment with so few side effects. Yes, I lost my hair and my fingernails, and I had some digestive problems, but I was indeed lucky.

I like to think some of my success with the treatment has to do with three decisions I made early on. First, I decided to be candid about my cancer and discuss it with anyone who was interested. Second, after reading the excellent Life Over Cancer: The Block Center Program for Integrative Cancer Treatment by Keith Block, M.D., a Chicago oncologist, I decided to eliminate red meat and dairy products from my diet. Block points out that the Japanese, for example, have significantly lower rates of cancer than Americans and eat significantly higher amounts of seafood. Summarizing several studies, The Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine at cancerproject.org concludes, “Even within Japan, affluent women who eat meat daily have an 8.5 times higher risk of breast cancer than poorer women who rarely or never eat meat.”

I began eating broiled or baked fish six or seven days a week combined with lots of beans, fresh fruits, vegetables, and nuts. I also started taking whey protein, flaxseed, and fish oil supplements.

Although some oncologists advise against strenuous exercise during chemotherapy, my third decision was to continue running and weightlifting, something I had been doing for more than 25 years. Block says, “My own clinical experience … has repeatedly confirmed the therapeutic benefits of exercise for people with cancer. Even walking … for three to five hours a week is correlated with a 50 percent decline in mortality from breast cancer.”

There’s also something else—a strong foundation of spiritual support. In his book, Block encourages meditation, spiritual disciplines, and connection with a loving community or support group. I try to spend time every morning in prayer, meditation, and reading the Psalms and other Bible passages. I know I could not have survived my year of treatment so easily without my faith and dozens of supportive friends in our a loving congregation at at St. George Orthodox Christian Church in Fishers, Indiana. And Elise’s prayers, cheerful outlook, and daily encouragement also made a tremendous difference.

When the treatment phase came to an end, I celebrated by running the Indianapolis 500 Festival Mini-Marathon, the largest 13-mile race in the country. At 7:30 a.m. on May 7, 2011, nine days after I finished radiation treatments, we were off. When I finished three hours and 28 minutes later, I ranked 26,307th out of 35,000 runners. Of course, I didn’t care where I placed. I was a winner. I ran another half marathon in October 2012 and, as you read this, I will be running another one. I plan to complete at least one half marathon a year for as long as I am able. As Robert Frost wrote, “The woods are lovely, dark and deep. But I have promises to keep and miles to go before I sleep.”

Related: Men and Breast Cancer: The Facts

Hospice Girl Friday | ‘Survivor’s Guilt’

Devra Lee Fishman’s dear friend and college roommate, Leslie, died from breast cancer one month shy of her 46th birthday after a four-year battle with the disease. Being with Leslie and her family at the end of her life inspired Devra to help care for others who are terminally ill. Each week, she documents her experiences volunteering at her local hospice in her blog, Hospice Girl Friday.

Before my friend Leslie died, I thought hospice was for old people with cancer. According to the Hospice Foundation of America, approximately two-thirds of hospice patients are over the age of 65, which means that one-third are younger than 65. And while many are diagnosed with cancer, I’ve seen just as many patients at my hospice with pulmonary or heart disease, neurological disorders, Alzheimer’s, AIDS, or complications from any number of health issues.

When I check the census at the beginning of each shift I get a quick overview of the current patients: their names, diagnoses, ages, and dates of admission. Also listed for each patient is the name and relationship of the main point of contact. All of this information is helpful as I prepare to make my rounds. I always look at the ages of the patients first, hoping to find that they are older than I am–preferably much older. That way I won’t have to think about my survivor’s guilt–how it could just as easily be me instead of them. But every week there is at least one patient my age or younger (I am 53), and every once in a while, all of the patients are. Those days are the toughest.

One recent Friday there were five patients: a 52-year-old woman with lung cancer; a 33-year-old woman in a diabetes-related coma; a 46-year-old man with HIV/AIDS; a 49-year-old man with end stage kidney disease; and a 51-year-old woman with breast cancer. I felt my stomach start to roil when I read the census. I would have preferred to stay at the volunteer desk and not see any patients for my entire shift, but I swallowed my survivor fear and made my rounds.

My first stop was room five, the woman in a coma. Her mother was there and said they were both fine for the moment so I moved on to the 46-year-old man in room six. He seemed to be sleeping so I tip-toed out and walked into the room of the 52-year-old woman with advanced lung cancer.

Her name was Laura, and she was sitting up in bed when I walked in. She was rocking back and forth with her palms on her lower back and watching The View on her small flat-screen TV. I read in the volunteer notes that she used to be a dancer; she looked tall, lean, and muscular, but she was also bald and jaundiced from her cancer and chemo treatments. If I didn’t already know her age, I would have guessed she was in her 70s. Cancer–or the treatment–does that sometimes. I noted a pile of peanut M&M packets on the nightstand next to her untouched breakfast tray.

“Peanut M&Ms are my favorite candy,” I said to break the ice after I introduced myself. Focusing fully on the patient was difficult because I kept thinking: She’s younger than I am. I could be in that bed.

Laura glanced over at the stash. “My boyfriend keeps bringing those because he knows I love them. I just don’t have much of an appetite anymore.”

I wanted to have more of a conversation with her, and asking about her boyfriend would have been my next move, but when a patient mentions some sort of physical symptom like a loss of appetite, it’s important to try to find out if he or she is experiencing any other discomfort. The nurses visit as often as they can, but a patient’s comfort level can change minute-to-minute so I always try to help by passing along any time-sensitive observations.

“How are you feeling otherwise? Are you comfortable?”

“Pretty much,” Laura said. “My back still really hurts.”

That explained the rocking. Back pain is a common complaint with lung cancer patients, but should be fairly easy to fix so I said, “I’m sorry to hear that. I’ll tell your nurse.”

“Why are you sorry?” she asked. “It’s not your fault. I’m the one who smoked.” She said this without the slightest note of self-pity or anger.

“Fair enough,” I said, trying to sound as neutral as she did. My ‘sorry’ was meant to be empathetic instead of sympathetic, but I knew to follow her lead and then drop it. There was a pause between us, and before I could stop it, a feeling of relief rushed in along with the thought: Maybe I wouldn’t be in that bed after all because I don’t smoke.

On the days when the patients are younger than I am, I marvel at the randomness with which we move through life, as though we’re all playing one big round of musical chairs, dancing around one moment and eliminated from the game the next.

On those same days I also feel a deeper empathy for the patients and their loved ones, and I’ve often sensed the same from the hospice nurses and doctors. I know that cancer, diabetes, HIV, and other diseases do not discriminate by age, yet sometimes I wish they did. I see too many hospice patients who just seem too young to die–possibly because I feel like I am too young to die–and it feels unfair that they could not find a chair when the music stopped. Then again, I have no idea what age is “old enough” to die, so I continue to work through my survivor fear and do my best to help all of the patients in my hospice find some comfort at the end of their too-short lives.

Previous post: The Power of Listening Next post: Coming soon

Going it Alone

Shortly before my 39th birthday, when I was taking a shower, I felt a lump about the size and shape of a pea in my right breast. I felt a chill go through my body. A week later, on my 39th birthday, I got a biopsy. When the doctor called with the results (I was setting out the birthday cake for my older son’s seventh birthday), the news was bad: I had breast cancer. I wanted to cry, but I couldn’t. It just felt surreal.

In literature and film, medicine is often depicted as a paternalistic profession, with patients given little information and expected to follow their doctors’ orders blindly. In real life, my experience was the opposite. Instead of having an all-knowing doctor telling me what to do, I found myself with a team of doctors relying on me to make the critical treatment decisions. I was like a president with advisors, but I knew nothing about the topics, and the choices and the information were overwhelming. What I expected was Dr. Brilliant Guide; what I got was Dr. Me.

My first appointment was with a pre-eminent breast surgeon at a top-rated comprehensive cancer center. She carefully laid out the options for me: lumpectomy with radiation or mastectomy with reconstruction. The lumpectomy would mean a less invasive procedure and a quicker recovery but also require several weeks of daily radiation and a lifetime of mammograms and MRIs. The mastectomy would entail more invasive surgery and a longer recovery time but eliminate the need for radiation and ongoing screening. Long-term survival odds were the same. My surgeon had no recommendation either way.

Anxious to get her to cast a vote, I tried a personal approach. I had Googled my surgeon before the appointment and found that we were of the same age and ethnicity, and we were both mothers. “You and I could be sisters—twins, even,” I told her. “If you were in my shoes, what would you do?”

She paused before answering. “Whenever women ask me that, I tell them that it’s a personal decision, and that I can’t make it for them,” she said. “But when I look at you, I see myself. I would choose a mastectomy with reconstruction.”

I was grateful for her answer but also frustrated on behalf of other patients. Why do doctors express their much-more-informed opinion so reluctantly?

I had more decisions to make when I met with a plastic surgeon. He laid out the options: saline implant, TRAM flap (which uses skin, fat, and muscle from the belly region to construct a breast), or LAT flap (which uses skin, fat, and muscle from the back region to construct a breast). I chose to get an implant, but I developed severe capsular contracture, which is when scar tissue forms around the implant and causes painful stiffness and hardening of the tissue. After multiple surgeries, I had to remove the implant altogether. In retrospect, I wish I’d considered the choice of no reconstruction at all, but it was not something that I even thought to discuss with the plastic surgeon, nor did he mention it to me.

The hardest phase of my medical training was choosing an oncologist, the person responsible for administering chemotherapy and other systemic cancer treatments. Weeks had passed since my surgery, and I was convinced that the cancer was already beginning to spread. I wanted to begin chemotherapy right away. But the oncologist offered me the most intimidating set of choices yet.

I could take four rounds of Adriamycin plus Cytoxan, either at four-week or three-week intervals. I could add four rounds of Taxol or Taxotere, again at either four- or three-week intervals. I could participate in a clinical trial in which I would receive either a new drug called Herceptin or a placebo. After my chemotherapy ended, I could choose to take five years of an oral hormonal drug called Tamoxifen, or I could suppress my ovaries by taking a drug called Lupron or Zoladex and take five years of an Aromatase Inhibitor such as Letrozole (brand name Femara), Exemestane (Aromasin), or Anastrozole (Arimidex), or I could take five years of Tamoxifen and follow it up with another five years of an Aromatase Inhibitor.

My head was spinning. Having spent an hour describing the options, the oncologist had run out of time and had to move on to her next patient. Rather than recommending a particular course of treatment, the oncologist told me and my husband to go home and think about it and make an appointment to meet with her again.

I didn’t want to wait several more weeks mulling over treatments I didn’t really understand. At my friend’s suggestion, I met with another oncologist. He offered the same options as the first oncologist but recommended a specific course of treatment and gave strong supporting reasons for it. I appreciated that he was advocating an aggressive approach (adding a third chemotherapy agent and combining ovarian suppression with an Aromatase Inhibitor). But, mostly, I was grateful for a straightforward answer. He became my oncologist.

For young women with breast cancer, treatment decisions often extend beyond surgery, radiation therapy, and oncology to medical specialties such as genetic counseling, fertility planning, gynecology, psychiatry, physical therapy, and primary medicine. Unfortunately, even at a comprehensive cancer center, the patient must coordinate these various disciplines. And if you go “a la carte” like I did, mixing and matching doctors in different practice groups and at different hospitals, good luck.

In the end, I had to create an Excel spreadsheet just to keep track of my appointments: breast surgeon every six months; mammogram every year (ideally just before the breast surgeon visit so that we could discuss the results); MRI every year for the first two years (ditto, but scheduled six months from the mammogram); oncologist every four months for the first five years, then every six months thereafter; ditto for the blood test with tumor markers; PET/CT every year for the first three years; bone density test every year for the first five years (to track the bone thinning effects of the Aromatase Inhibitors); MUGA heart scan every few months for the year of Herceptin (owing to the cardio-toxic effects of Herceptin and Adriamycin); gynecologist every six months; primary physician every year; and so on. I was able to keep track of this because I’m fairly organized. But what about most people?

In many respects, the collaborative approach that doctors take to cancer treatment is welcome. No one wants a high-handed doctor making treatment decisions without the patient’s involvement or understanding. But a patient can’t in the end play the role of doctor. We might want to know why a doctor is recommending something; but we still want a recommendation. Also, many of us need a guide just to navigate all the appointments and logistics, which can be Byzantine.

Today, nearly eight years after my initial diagnosis, I continue to be vigilant in monitoring my health. (Hormone-sensitive cancers like mine have a “long tail”—meaning they can recur 10, 15, even 20 years after diagnosis.) I read articles and books about cancer. I attend lectures and take notes about the latest treatments. And I participate in a breast cancer support group.

If, knowing what I know now, I were able to go back in time and advise myself on how to be Dr. Me, I would have said three things that I also say to new acquaintances in similar circumstances. The first is that you should always bring a family member or friend to your appointments and have him or her take notes. Often, we patients are so overwhelmed that we can’t remember what we were just told or don’t ask any questions. The second is that you must take care of your whole self. Treat yourself to delicious and healthful food every day. Watch a funny movie and laugh with your friends. Take naps and hot baths as needed. The third is that you should feel free to complain. I have seen too many friends suffer in silence, whether it’s nausea from chemo (doctors often prescribe the cheapest anti-nausea drugs before moving up to the more powerful stuff) or simply trouble getting an appointment. If the front desk or support staff are unhelpful, tell your doctor—doctors don’t want to lose you as a patient.

In an ideal world, of course, no patient would have to shoulder so many responsibilities along with trying to get well. One of the best improvements that could be made would be for patients with cancer to have a “patient advocate.” If you were diagnosed with cancer, the medical center would partner you with a professional patient advocate who would guide you through the cancer treatment process. The patient advocate would set up appointments for you, make sure your care was coordinated, and offer general health-related suggestions (alternative treatments, massage, nutrition classes, support groups). The advocate might even accompany you to appointments and help you with decision making. This would go a long way toward letting those with serious conditions have the luxury of being patients, so that they don’t have to be Dr. Me.

Ann Kim is the president of Bay Area Young Survivors (BAYS), a support group for young women with breast cancer in the San Francisco Bay area.

Article originally published at Zócalo Public Square (zocalopublicsquare.org).

Help When You Need It

The American Cancer Society (cancer.org) provides helpful information about all types of cancer, and offers amazing programs such as peer support, free wigs and cosmetics, and free transportation to appointments.

For general information about breast cancer, as well as a helpful online community (chat boards), breastcancer.org is a good resource.

Other websites that Ann recommends:

Right Action for Women (rightactionforwomen.org), founded by actress Christina Applegate, educates women about what it means to be at “high risk” for breast cancer and provides aid to those without insurance or the financial flexibility to cover the high costs associated with breast screenings.

Casting for Recovery (castingforrecovery.org) provides an opportunity for women with breast cancer to gather in a natural setting to learn the sport of fly fishing, network, exchange information, and have fun.

Cleaning for a Reason (cleaningforareason.org) partners with maid services to offer free professional house cleaning to women undergoing treatment for any type of cancer.

Little Pink Houses of Hope (littlepinkhousesofhope.org) offers weeklong retreats in North and South Carolina for breast cancer families, providing food, lodging, and activities. Participants provide transportation.

Cancer and career: Many facing cancer have questions about how the disease will affect their jobs. The Disability Rights Legal Center (disabilityrightslegalcenter.org) and Cancer and Careers organization (cancerandcareers.org) are great resources to help with these issues.

Helping Men Become Better Caregivers

For many families, caregiving duties automatically fall to women. According to an AARP study, most caregivers are female. But the same study showed that more men are starting to take on the caregiver’s role. That’s good news on the gender equality front. But if things are getting fairer, there’s still progress to be made. And to put it plainly, male caregivers could use a little help.

Marc Silver discovered this firsthand when his wife was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2001, and though he stood by her and eventually figured out how to be a good caregiver, he’s the first to admit he made plenty of mistakes along the way. After their ordeal (his wife is doing fine at present), he wrote an instruction manual to help other caregiving-challenged men. His book is called Breast Cancer Husband, How to Help Your Wife (And Yourself) Through Diagnosis, Treatment, and Beyond. I recently caught up with Marc to talk about his experiences and to find out what advice he has for other men.

Q: Why do men need extra help when it comes to caregiving?

A: Caregiving is a role that a lot of guys are unfamiliar with, and particularly in the case of breast cancer, it is thrust upon them with no time for preparation. Personally I just remember feeling totally clueless and getting a few things completely wrong.

Q: For example?

A: Well, my wife Marsha called me immediately after her diagnosis. She’d just been told out of the blue that she had breast cancer. She was looking for some husbandly advice and solace, and my first reaction over the phone was, “Ew, that doesn’t sound good.”

Q: Uh, oh.

A: It gets worse [laughs.] We continued to talk a bit more, but only about logistics, when what she was needing at that point was sympathy and compassion. Then, at the end of the conversation I hung up, stayed at work all day, and didn’t come home until the usual hour.

Q: What did your wife say about that?

A: Marsha told me later, “I must have called the wrong husband.”

Q: In doing research for your book, did you find that your initial reaction—let’s be nice and describe it as missing her emotional cues—was a common one?

A: There are plenty of examples of men who ran straight home to be there for their wives when a cancer diagnosis was made. But yes, many men make mistakes like these, and I’ve heard of worse.

Q: Like what?

A: After a speaking engagement for my book, a couple came up to me and the husband told me that his reaction to his wife’s diagnosis was, “Well, you want to stop for dinner at Hooters?” I asked him if he was trying to be ironic or funny, but he insisted he was just thinking about a good place to get a meal.

Q: Sounds like men can’t cope initially and go into autopilot. Is this denial?

A: Yes, I think so. But it’s a very human reaction. One therapist I interviewed for the book said, “Nobody is sitting there saying, ‘Oh gosh, I hope I get to be a caregiver for a loved one who is diagnosed with cancer.’”

Q: So, guys shouldn’t beat themselves up too much about initial blundering?

A: No, they shouldn’t. That is very important. It is inevitable that you are going to do things that are going to tick your wife off or be not the kind of things she needs at that time. But you can learn from that. A lot of woman said to me that the motto for the husband is: “Shut up and listen.”

Q: Is there something inherently different about men that makes it harder for them to be good caregivers? Or, are men just not socialized to get it? Is it nature or nurture?

A: In my research I found a little bit of both. Men are simply not taught to tune in to others emotionally the way women are. On the nature side, doctors point to studies showing women have more of the hormone oxytocin, which promotes empathy.

Q: Still, it sounds like you’re saying, with some help, men can and do learn to be better caregivers.

A: Yes, absolutely. A big challenge is that men like to be problem-solvers. Instead, they need to learn that their role, as a caregiver, is to be an echo or a foil: Let her talk things through with you without interrupting to say, “here’s what you should do.” You’re not supposed to be in charge here. She is the boss.

Q: Does that make you the assistant?

A: Yes, exactly.

Q: Can you give an example of being supportive, without taking charge?

A: It is very common for a patient to be overwhelmed by all of the medical information. So, it’s important to join her at all medical appointments. Make lists of her questions for the doctors prior to each visit, and keep the list in front of you during the visit to make sure all of them get answered. Also, take good notes on these medical conversations so you can go over the details later.

Q: Your book title stresses helping your wife and yourself. How so? Isn’t that selfish?

A: Part of what you have to do as the caregiver is to be selfish sometimes. Whether it’s going out for a bike ride or watching a movie you like. You need time for yourself to recharge.

Q: So, if caregivers have a need to, say, go play golf or take a bike ride for a few hours, that’s ok?

A: Yes, but I would always ask my wife’s permission first. I interviewed Cokie Roberts for the book. She said when she was going through breast cancer, friends would call up and ask what could they do. And her first response was: “Play tennis with my husband.” It is certainly much harder to be the patient, but it is tough to be a caregiver too.

Steven Slon is the editorial director for The Saturday Evening Post. This column was first published by Beclose.com.