Death of a Sales Scheme: Encyclopedia Shysters of the Door-to-Door Age

Moses Pray, Ryan O’Neal’s character in 1973’s Paper Moon, cons recent widows into buying holy books with the claim that their deceased dears had put in an order shortly before passing. The heinous trick plays on the poor women’s grief and belief, powerful sentiments ripe for exploitation.

Another powerful sentiment is the wish for one’s children to grow up with culture and knowledge. It might not sell bibles; but the desire for prominence was once co-opted to peddle a pricier set of books.

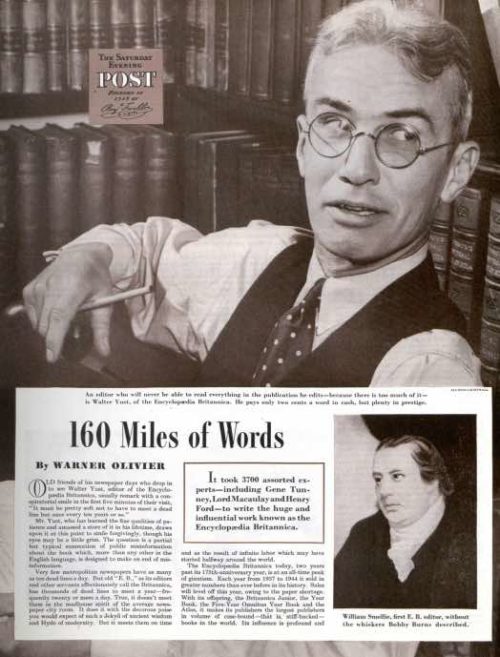

Encyclopædia Britannica was in a hole when Sears, Roebuck & Co. took over the title in 1920. Britannica was sold mostly by mail-order at the time, and it only released a new edition every 25 years or so. The Post’s two-part series “160 Miles of Words” from 1945 tells the quirks and disparities of publishing such a monumental work as well as the transformation of its business practices after Sears’ secretary and treasurer E. Harrison Powell stood at the helm: “Powell started from scratch to build an outside sales organization and establish branch sales offices in key cities of the country. Sales began to go up. But strange letters of complaint also began to come into the Britannica home offices in Chicago.”

Powell — perhaps unintentionally — had employed some “old book” salesmen in his staff, and the shysters used their own tricks to get the job done: “One of their favorite methods was the giveaway, or “you-have-been-selected” trick. They would visit a prospect and tell him: ‘The Encyclopædia Britannica is initiating a new advertising campaign, and as one of the most prominent citizens of your community, we have selected you to receive a set of the Britannica free — absolutely without any cost to you.” The word “free” was as much of a misnomer as “Britannica” (the book has never been published in England) since the promise was soon followed with an offer for the newly-introduced subscriptions. The total price proved to be no bargain after all.

Powell revamped his sales department after the “shock” of discovering its unsavory business practices, and he called in a new manager to institute a rigid, thorough program for direct sales. The new protocol declared, “Appointments are made by telephone, either in the prospect’s office or in his home. If it is a home appointment, the salesman makes it clear to Mrs. Prospect that he wants to see her when Mr. Prospect is at home, so that he may talk to both of them together.”

The story of sales deception ends there, at least in the Post article. But misleading encyclopedia sales tactics never really disappeared. According to a 1968 New Republic story, all of the major encyclopedia companies have seen run-ins with the Federal Trade Commission over deceptive sales tactics as well as specious hiring ads. Britannica received a cease-and-desist order from the FTC in 1961 and a complaint in 1976. The latter claimed the book giant was misrepresenting sales jobs as advertising analysis and public relations. Furthermore, Britannica was promising salaries for their salesmen that just didn’t add up. One FTC violation sounds familiar: “Persons engaged by respondent do not contact people in their homes primarily for the purposes represented by respondents.”

Of course, Encyclopædia Britannica has ceased printing its volumes. Who needs 129 pounds of information on the shelf when you can scroll through it for free on a screen? Sure, it was authoritative, but just as Wikipedia receives flack for occasional absurdities and falsehoods, Britannica faced a learning curve with its card catalog when green editors “classified Virginia Reel under biography, Defense Mechanism under military, Gallstones under geology, Incest under business and industry, and Pope Innocent under law.”

The days of slick, smooth-talking men promising the social status only an encyclopedia set can bring to stay-at-home moms are over. Besides, people have other ways of signifying prominence these days. Unfortunately, most of them have nothing to do with knowledge.

See the Post‘s recent story, “The Death of the Encyclopedia.”