3D Printing the Old-Fashioned Way

In 2014, a team of imaging experts with Smithsonian created the first-ever 3D-scanned presidential portrait. In a little over seven minutes with a sitting President Obama, the team was able to capture sufficient data to 3D-print a life-size bust of him that was an objectively accurate rendering of his features.

And yet, the resulting model was lacking a lifelike quality.

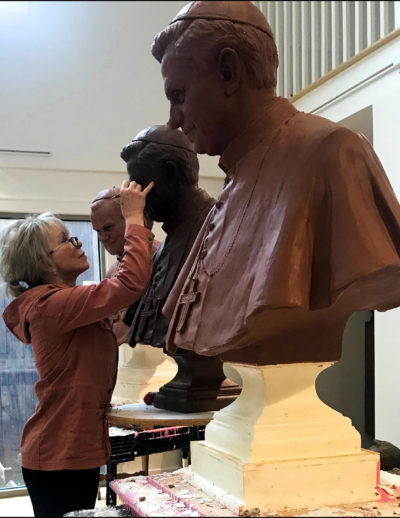

At least, that’s what bronze sculptor Carolyn Palmer says. She remembers thinking that her profession could be in jeopardy with the arrival of this new technology. Despite Obama’s abundance of soul and personality, the 3D-printed presidential portrait is “very cold,” Palmer says. “In my belief, the sculptor brings life into a piece.”

Her theory about the necessity of the artist in sculpture seems to ring true, even as leaps in technology have made such reproductions possible. Palmer is busier than ever, receiving a constant stream of commissions for sculptures in marble and bronze. Her bronze busts of Franklin D. and Eleanor Roosevelt are currently travelling with Rockwell, Roosevelt, and the Four Freedoms, an exhibit organized by the Norman Rockwell Museum. Opening last May in New York, the exhibition will have made stops in Michigan, Washington, D.C., Normandy, Houston, and Denver before it closes at the Rockwell museum in 2020.

Rockwell’s Four Freedoms series was originally published in this magazine as an artistic response to a speech President Roosevelt gave to Congress in 1941 on the eve of World War II. The paintings, Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Worship, Freedom from Want, and Freedom from Fear, were published alongside essays by distinguished writers and became emblematic of the war effort.

“Who would say no to travelling with the Norman Rockwell Museum?” Palmer says. She visited the exhibit in New York, and she was thrilled to see her Roosevelt sculptures sitting among the works of the masterful American painter. Rockwell gained a reputation for painting faces so full of personality they seem as though they might come to life, and Palmer strives for a similar effect in her own work.

For 22 years, she has practiced the lost-wax method of casting bronze, which has itself been used for thousands of years. First, the artist creates a model in clay. This is covered with silicone rubber that will capture the finest details of the sculpture, then plaster for support. A wax model is made from this mold, which is then dipped into a ceramic slurry. The wax is “lost” when this new mold is heated. Finally, the bronze can be poured.

At every step, there are ample opportunities for disaster. A completed bronze sculpture requires an artist to oversee the work of many skilled artisans, and it can take months to finish. Palmer says she remains involved in the process at every step, particularly since she lost Edith Wharton. Her small clay model of the writer had been diligently sculpted with fine details, but it was destroyed when she handed it over to a newbie moldmaker.

Palmer received her degree in art education from Nazareth College, and she taught painting privately for a time while taking commissions for portraiture and logo design. She received her first opportunity to sculpt when one of her clients asked her to refer an artist to create a bronze Thomas Jefferson. “I said, ‘Oh please give me this opportunity, because I know I can sculpt!’ I offered to invest in the clays and told him if he didn’t like the piece he didn’t have to pay for it to go further into bronze,” Palmer says. Although she hadn’t studied sculpting much, Palmer remembered visiting her grandparents in Siesta Key when she was a little girl and carving forms at the beach: “Ever since I was a little girl I would make faces and people in the sand, and I would literally make them look like they were coming out of the sand.”

Since that first successful commission, Palmer has racked up an impressive resume of statuary that will stand in public and private spaces for generations. In 2015, she was chosen out of 68 sculptors to replace the infamous “Scary Lucy” statue in Lucille Ball’s hometown in New York. She has also completed likenesses of four popes, the Wright brothers, President Bill Clinton, Mario Cuomo, and Dr. William Osler. The last one might not ring a bell, but he is often described as the “Father of Modern Medicine” for his innovative practice of residency programs and bedside medical education. “There must not be a lot of Osler sculptors out there,” Palmer says, since she’s received orders on her Osler sculpture from around the world.

In the age of 3D-printing and automation, it might be difficult for many viewers of bronze and marble sculptures to appreciate the skilled process that goes into creating a lasting lifelike form. At best, they can be timeless, glowing tributes to humanity to marvel and inspire passersby. At worst, they can resemble the stuff of nightmares and serve as fodder for viral social media snark. The difference is all in the skill of the artist.

Palmer has always admired the works of sculptors like Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, a 19th-century French artist. “He had a great taste for movement and spontaneity and he broke away from stiff, stoic looks on sculptures,” she says. “He could capture the intensity of a person’s personality or soul or essence.” Palmer refers to the bust of Robert Fulton by Jean Antoine Houdon that sits in the Metropolitan Museum of Art as an example of a work that comes to life. “When I start on a piece, I try to feel their personality,” she says. “You have to look with your heart, get to know them like an actor or an actress would get to know a role.” It’s certainly a slower process than 3D imaging, and much less forgiving. She’s currently chipping away at 800 pounds of marble in her studio as proof of that.

Featured image: MZ Studios