How a Road Less Traveled Led to Baseball’s Boys of Summer

As Americans long for the return of baseball — now indefinitely delayed due to a virus that has shuttered the country — there is no better time to reflect on a soulful interview that sparked one of the game’s most nostalgic human narratives.

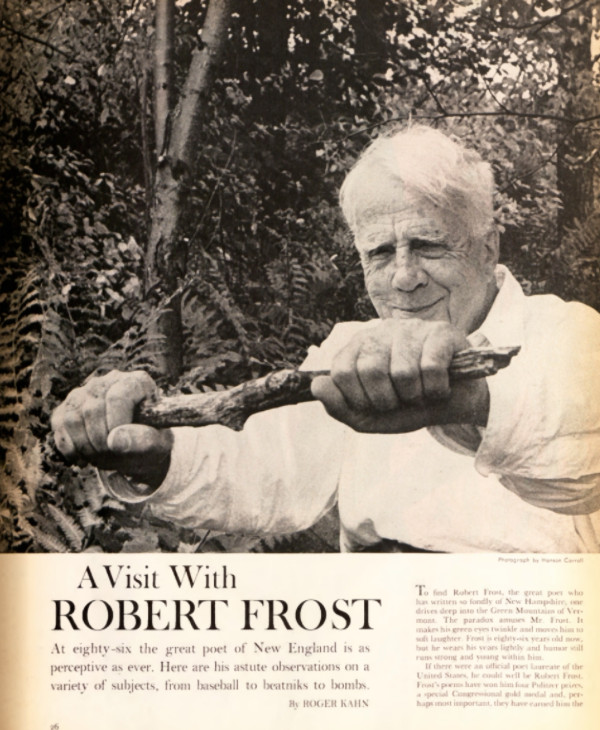

In 1960 The Boys of Summer author Roger Kahn was in his early 30s when he drove along backroads bordering streams in the Green Mountains to spend the afternoon with New England poet Robert Frost. When the sportswriter reached the end of a dirt road, he got out of his car and walked up a hill to Frost’s cabin, where he lived alone, from May until the leaves changed in the fall, when the poet returned to Cambridge.

At the time, Kahn was a celebrated sportswriter who covered the Brooklyn Dodgers for the Herald Tribune in the early 1950s. He based The Boys of Summer on players such as Jackie Robinson, who broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball, Pee Wee Reese, Preacher Rowe, Carl Erskine, and Roy Campanella. Twenty years after his Boys retired, Kahn caught up with his middle-aged Boys as they struggled through life.

Kahn had met Frost at the Bread Loaf Writers’ conference at Middlebury College in 1951, where the poet pitched to the writer in a summer baseball game with the spine of the Green Mountains in the background. It was there, on that grassy field, when a love for America’s Pastime connected two artists who appreciated the delicate, often brutal plight of the aging athlete.

The World Series was a month away when the 86-year-old snow-headed poet greeted Kahn, wearing blue slacks and a ragged gray sweater. With a face as weathered as the mountain, Frost cut a strapping agrarian frame from years of laboring behind a plow, and daily hikes through the woods, where he conjured phrases about the road less traveled.

The Saturday Evening Post’s “A Visit with Robert Frost” interview drew a response that stunned both Kahn and Frost. Hundreds of letters poured into the magazine from readers. Many enclosed the November 19th feature, asking Kahn to autograph it because they knew he captured Frost in his purest form toward the end of his life.

The Interview

1960 was a tumultuous year. The United States announced plans to send its first wave of troops to Vietnam, John F. Kennedy narrowly won the presidential election, the Soviet Union shot down a U2 spy plane, and Fidel Castro nationalized American oil and other interests.

Xerox introduced the first copier and computers with punch cards were transforming society, yet Frost lived like a pioneer in a previous century. He didn’t have a desk. A ragged row of books lined the shelves of his sparse living room. Frost never learned to type and agreed to the interview on the condition that a tape recorder was not used, feeling the device would disrupt the natural flow of the conversation.

Working on a portable typewriter, Kahn noted that Frost “runs a conversation as a good pitcher runs a baseball game, never giving you quite what you expect.” That afternoon Frost paced around the living room, holding his chin in his hands as he pondered the unfinished business of Russia and Castro, two years before the Cuban Missile Crisis captured headlines. As a poet, Frost spoke of beatniks, loneliness, and the natural, unchanging rhythm of the tides. As a farmer, he explained why he thought it was important for people to be self-sufficient and for every man to know how to live poor.

On the ballfield Frost was a pitcher, and a damn good one who didn’t have a problem with players who slid into base, spikes up. He grew up going to games at Fenway Park and rooted for the Red Sox. His favorite player was Ted Williams, whose last game was eulogized by John Updike on October 22, 1960, in his lyrical New Yorker essay, “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu.”

Some of Frost’s most memorable lines compared life to baseball. In a 1956 Sports Illustrated story the poet sat in the grandstand and wrote, “Some baseball is the fate of us all. For my part, I am never more at home in America than at a baseball game.” He also turned this phrase: “Poets are like baseball pitchers. Both have their moments. The intervals are the tough things.”

That afternoon, as the sun lowered over the mountains, Kahn asked his friend, “Is there one basic point to all fine poetry?”

“The phrase,” Frost said, offering this explanation: “A clutch of words that gives you a clutch at the heart.”

A decade later, Kahn clutched readers’ hearts with his true-to-life account of his Dodgers when they hit middle age.

The Last Surviving Boy of Summer

Roger Kahn passed away at a nursing facility in Mamaroneck, New York, on February 6, 2020. As fans from Brooklyn to Los Angeles celebrated his poetic take on baseball, almost all of his “Boys” were gone. Jackie Robinson died at age 53 in 1972, catcher Roy Campanella, who was confined to a wheelchair after a car accident, died in 1993. Pee Wee Reese passed in 1999 and Duke Snider died in 2011, just to name a few.

One particularly resilient player who shared a love of poetry with Kahn and Frost resides in his hometown of Anderson, Indiana.

Ninety-three-year-old Dodgers pitcher Carl Erskine returned to Indiana with his wife and family 60 years ago. Kahn affectionately branded Erskine as “Oisk,” based on the way Brooklyners leaned over iron railings at Ebbets Field, rooting for their boy “Cal Oiskine.”

Erskine grew up pitching into a strike zone painted on the side of a barn. He played his entire career with the Brooklyn and Los Angeles Dodgers, from 1948 through 1959. As a starting pitcher, Oisk helped the Dodgers collect five National League pennants, winning the World Series in 1955 against the New York Yankees. At the high point of his career in 1953, Erskine won 20 games and set a World Series strikeout record in a single game on October 2, 1953, in “chilly sunshine” as described by Kahn.

Reporters and writers (like myself) sought out Erskine after Kahn’s passing, asking him questions about the author and his Boys. When I called on a frozen Valentine’s Day, his wife Betty cheerfully answered the phone as the temperature plummeted across the Indiana plains. Erskine was tinkering with something in the garage when he politely came into the house to take my call.

That day he explained why The Boys of Summer will endure as one of America’s most relatable baseball classics. “Roger saw life in more depth than any other beat sportswriter. He drew out the broad personalities of ballplayers in an era of hero worship,” Erskine said.

Kahn always praised Erskine as his most empathetic player. In The Boys of Summer the sportswriter focused on a life decision the soft-spoken Hoosier made to return to Indiana at age 32, staying put to make a better life for his son Jimmy, born with Down syndrome in 1960.

Erskine explained that The Boys of Summer is really two books. “The first part is about Kahn’s childhood, growing up in Brooklyn, where his mother never read him a baseball book, but taught him about Greek mythology, which he applied to ballplayers. The second part is about athletes who age,” he said. The title is derived from the opening stanza of a poem by Dylan Thomas, the struggling Welsh playwright who died at age 39 in 1953. It reads:

I see the boys of summer in their ruin

Lay the gold tithings barren,

Setting no store by harvest, freeze the soils.

The Brooklyn Dodgers

The Boys of Summer was met with mixed reviews when it was released in 1972, when Kahn drank heavily and began to resemble Hemingway with a graying beard. Erskine said Walter O’Malley, who moved the team from Brooklyn to Los Angeles, did not like the book because he felt it played on the bad luck and some of the unfortunate circumstances the players faced later in life.

“Kahn exposed this Dodger team that was snake bit – they all had some tough outcomes in life,” Erskine said, recalling that his roommate Duke Snider was not pleased about the way in which he and his family was portrayed.

“I never felt that way. Kahn’s book reflected what real life is like,” he said very matter-of-factly. “It had nothing to do with how many baseballs you hit or players you struck out – you ended up so human that you were just like everybody else.”

Author Gay Talese, who helped define literary journalism, described Kahn’s narrative as a book about ourselves in the October 26, 1972 issue of The Herald & Republican. “It is about youthful dreams in small American towns and big cities decades ago, and how some of these dreams were fulfilled, and about what happened to those dreamers after reality and old age arrived. It is also a book about ourselves, those of us who shared and identified with the dreams and glories of our heroes.”

After The Boys of Summer was published Erskine mailed Kahn a poem by Robert W. Service, entitled “My Masterpiece” about having good intentions but never following through. The sportswriter framed the poem on the wall by the fireplace at his home at Croton-on-the Hudson, New York. The last stanza reads:

A humdrum way I go to-night,

From all I hoped and dreamed remote:

Too late… a better man must write

The Little Book I Never Wrote.

Though Robert Frost, Roger Kahn, and Carl Erskine came from different worlds, the New Englander, New Yorker, and a Midwesterner will forever be united by a love of poetry and baseball. They also help us understand that some of the roughest and most unpredictable roads that life takes us down make us human.

Austin, Texas, writer Anne R. Keene is the author of The Cloudbuster Nine: The Untold Story of Ted Williams and the Baseball Team That Helped Win WWII, being released in paperback on April 21st.

Featured image: © SEPS

Reveling in the Past of America’s Favorite Pastime

When Major League Baseball’s All Stars take the field in July at Busch Stadium in St. Louis, thousands of fans will be thinking of Mel Ott and Eddie Joost instead of Derek Jeter and Albert Pujols. They’re keepers of the flame for teams alive only in sports history books and their own memories.

The New York Giants, Washington Senators, Boston Braves, St. Louis Browns—thousands of diamond enthusiasts still hold allegiance to these bygone teams. They organize fan clubs, celebrate great moments at meetings, and swap items on eBay every day all in the name of honoring the past of America’s pastime.

And their own youths.

Ron Gabriel grew up two miles from Ebbets Field, home of the Brooklyn Dodgers, at a time when you could hear radio announcer “Red” Barber’s play-by-play “from every open window in Brooklyn,” he recalls. These days Gabriel lives in Chevy Chase, Maryland, but Brooklyn never quite left the boy. On October 4, 1975, at 3:44 p.m., he formed the Brooklyn Dodgers Fan Club. It was 20 years to the minute of the team’s first and only World Series victory.

“I realized this intensity needed someone to bring [Dodgers fans] all together, to kind of act as a clearinghouse. I was confident I could do that.”

Gabriel hosted annual meetings at his home (serving hot dogs and Schaefer Beer, a longtime Dodgers’ sponsor). When the 50th anniversary of the team’s World Series victory rolled around in 2005, he organized a commemorative dinner and passed out bumper stickers: We Loved the Brooklyn Dodgers — and we still do!!

But for Gabriel and thousands of fans of Dem Bums, the world changed when the team moved to Los Angeles beginning with the 1958 season. “I went into a state of shock,

and I still am, still can’t believe it.” Diehards were devastated and many, like Gabriel, never transferred their allegiance to another team. “Once a Brooklyn fan, always a Brooklyn fan,” he says.

There is a common thread that binds fans of defunct teams, a certain poetry in their recollections that are valentines to the boys of summers past. You can hear it in the way they share stories —always in the present tense. Bobby Thompson hits the “shot heard round the world,” Willie Mays makes his magical over-the-shoulder catch. With each retelling, there are new insights, a deeper understanding. The drama of the game continues to unfold. Instant replays, never distant replays.

“We’re in the Twilight Zone,” says Bill Kent, founder of the New York Baseball Giants Nostalgia Society. “To us, the old Giants are still alive. We relive their exploits.”

Kent grew up in the Bronx, a trolley and subway ride away from the old Polo Grounds in upper Manhattan. As a youngster, Kent would sometimes sneak into the ballpark by climbing over the fence before crews arrived and stake out empty seats with his friends. Other times, he’d get picked to turn the turnstiles at the entrance gate, earning spare change and free admission to the game. It was a highly coveted role. “There were always more kids than jobs.”

The Giants society is a loosely knit group of baseball fans, lawyers, teachers, sports writers, and even “a lady umpire and a lady baseball player” among them, who participate in an online discussion group and get together three times a year for what Kent calls schmoozing. Three or four people showed up at the first meeting held at a Chinese restaurant. Word spread, and Kent had to find larger quarters at an Italian restaurant. These days, meetings attract upwards of 50 and are often held in a church basement. Ten dollars pays for the pizza. There are even a couple of Dodgers fans and a sprinkling of Mets fans. “We don’t care. We have nice people, and if they’re not nice, they’re out,” he says.

The 1950s was a turbulent decade for baseball fans. In 1953, the St. Louis Browns played their last game at Sportsman’s Park before moving to Baltimore. Brownies pitcher Ned Garver, who won 20 games for the 1951 team that ended with a 52-102 record, once famously said: “Our fans never booed us. They wouldn’t dare. We outnumbered ’em.” At least their legacy is alive and well. The St. Louis Browns Historical Society and Fan Club is celebrating its 25th anniversary this year.

In 1954, the Philadelphia Athletics moved to Kansas City; in 1953 the Boston Braves moved to Milwaukee. And, of course, there was the twin sting for New Yorkers in 1958 when both the Dodgers and Giants made their way to California.

When the Philadelphia Athletics moved to Kansas City starting with the 1955 season, it wasn’t a surprise. But that didn’t make it any easier for fans like Dave Jordan. “For a couple of years it was clear the A’s were running out of money,” he says. The city couldn’t support both the A’s and the Philadelphia Phillies. Still, Jordan says when the mayor announced a “Save the A’s” committee, “I was one of few people who took him seriously.”

Jordan is chairman of the board of the Philadelphia Athletics Historical Society in Hatboro, Pennsylvania, a robust organization of 800 members spread coast to coast. The society puts out a bimonthly newsletter, runs a museum, and holds functions to which original players are invited. There are a few younger members, but Jordan says that for the most part, its ranks are filled with people who were Shibe Park regulars in the days of Lefty Grove, Jimmie Foxx, Eddie Collins, and Mickey Cochrane. One of Jordan’s favorite ballpark memories was the 24-inning game against the Detroit Tigers on July 21, 1945, called due to darkness.

“I kept score for 22 innings until I ran out of space.” He donated that incomplete scorecard to the Philadelphia A’s Society Museum and Library.

When the team moved on to Kansas City, Jordan stayed a fan. “In 1955 and 1956 I went to Yankee Stadium when Kansas City was in town, but it wasn’t the same. They changed the numbers of quite a few players, and eventually I had to face the fact that the Phillies were what we had left.”

Middle-aged fans are now golden agers and elder statesmen. “That’s something we at the society think about,” Jordan says. “Until recently, we always had a big breakfast in the fall, selling out with hundreds of fans showing up.” But, he says, as volunteers get older, functions are being scaled back.

There are also fewer players alive who wore the uniform.

The repercussions are showing up in the sports memorabilia market. Mike Heffner, president of Lelands.com, the oldest and one of the largest sports memorabilia auction houses, says the 1980s and ’90s were the boom days in memorabilia of defunct teams. “In the past few years, we’ve noticed a slowdown. People who were following teams in the 1940s and ’50s are mostly retired, some have passed away, and their collections have been sold.”

Some team items are valuable not because of the passion of their fans but because of their scarcity. The Seattle Pilots, for instance, played one year in 1969 before becoming the Milwaukee Brewers. “They didn’t have a huge fan base. There aren’t a tremendous

amount of them out there. But a uniform patch or a team-signed ball is very rare, so it’s tremendously collectible,” Heffner says. The Colt .45s (1962-1964), a squad that became the Astros, “were a terrible team, but they had really neat uniforms with a pistol on the front, so they’re highly collectible.” The latest franchise to join the brotherhood of bygone teams is the Montreal Expos, now the Washington Nationals. But don’t look for big returns there. “Canada and baseball don’t go together that well,” Heffner says.

Of course, for fans it’s not about money and not even about memorabilia. Their teams may not be in the box scores, and the ballparks may long be gone, but the boys of summer never grow old.