The Great War: October 10, 1914

From pages of the Post, October 10,1914: A forgotten American humorist turns war reporter, the war finds an unofficial theme song, and a doctor’s optimistic prediction of death is proved false.

A Little Town Called Montignies St. Christophe

By Irvin S. Cobb

You probably wouldn’t know the name Irvin S. Cobb unless, like me, you haunt the dustier shelves in used bookstores. Far in the back, usually in the humor section, I’ll find at least one of his books; he published over 60 titles between the 1900s and the 1940s.

Back in those years, Americans apparently couldn’t get enough of him. He was America’s highest paid short story writer. He also wrote movie scripts, appeared in motion pictures and on radio, traveled the lecture circuit, and hosted the 1935 Academy Awards. And he produced a mountain of work for the Post: [180 articles and stories between 1909 and 1922].

In 1914, Cobb decided to join the long line of American humorists who went to Europe to write a travel book. His series, titled “An American Vandal,” ran in the Post from March through June that year. No sooner had he returned to the States than the war started in Europe. Although he’d made his reputation as a humorist and storyteller, Cobb was still a journalist at heart. He jumped at the chance to report a war. He set off for the frontlines and, just across the French border, came across “A Little Town Called Montignies St. Christophe.”

It was a sleepy Belgian village when Cobb passed through it in the spring, but now he was giving the village a second, serious look.

“Something has happened to Montignies St. Christophe to lift it out of the dun, dull sameness that made it as one with so many other unimportant villages in this upper left-hand corner of the map of Europe. The war has come this way; and, coming so, has dealt it a side-slap.

“A six-armed signboard at a crossroads told us its name — a rather impressive name ordinarily for a place of perhaps twenty houses, all told. But now tragedy had given it distinction; had painted that straggling frontier hamlet over with such colors that the picture of it is going to live in my memory as long as I do live.

“Every house in sight had been hit again, and again, and again. One house would have its whole front blown in, so that we could look right back to the rear walls and see the pans on the kitchen shelves. Another house would lack a roof to it, and the tidy tiles that had made the roof were now red and yellow rubbish, piled like broken shards outside a potter’s door. The doors stood open, and the windows, with the windowpanes all gone and in some instances the sashes as well, leered emptily at us like eye-sockets without eyes.

“Until now we had seen, in all the silent, ruined village, no human being. The place fairly ached with emptiness. Cats sat on the doorsteps or in the windows, and presently from a barn we heard imprisoned beasts lowing dismally; but there were no dogs. We had already remarked this fact — that in every desolated village cats were thick enough; but invariably the sharp-nosed, wolfish-looking Belgian dogs had disappeared along with their masters. And it was so in Montignies St. Christophe.

“On a roadside barricade of stones, chinked with sods of turf … I counted three cats, seated side by side. It was just after we had gone by the barricade that, in a shed behind the riddled shell of a house, which was almost the last house of the town, one of our party saw an old, a very old woman, who peered out at us through a break in the wall. He called out to her in French, but she never answered — only continued to watch him from behind her shelter. He started toward her and she disappeared noiselessly, without having spoken a word. She was the only living person we saw in that town.”

Sidelights on the War

By Samuel G. Blythe

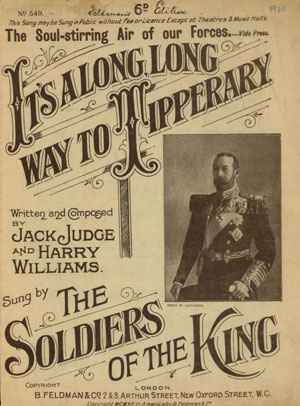

Just two months old and the war already had an unofficial theme song. Its brisk march tempo captured the spirit of the time so well that even today, when so much has been forgotten about the war, many will still recognize it as one of the signature songs of the conflict.

“The marching song and the fighting song of the British soldiers and the British sailors is not ‘God Save the King!’ or ‘Rule Britannia!’ or any other classic. The marching song and the fighting song of the British soldiers and the British sailors is: ‘It’s a Long Way to Tipperary!’ And that song is an inconsequential music-hall ditty, just as was ‘A Hot Time in the Old Town!’ And this is how the chorus goes:

It’s a long way to Tipperary,

It’s a long way to go;

It’s a long way to Tipperary—

To the sweetest girl I know !

Good-by, Piccadilly !

Farewell, Leicester Square !

It’s a long, long way to Tipperary;

But my heart’s right there!

“This is the song that the British soldiers and sailors sang when they went to France and to sea, which they sang in the fighting all along the line, and which they are still singing, and will sing to the end of the war. … It roars and rolls over the barracks and the camps; and even the French have re-constructed it as ‘Le Chemin a Teeperaire,’ and are singing it too.”

Listen to “It’s a Long Way To Tipperary” by the great Irish tenor John McCormack.

Read the entire article “Sidelights on the War” by Samuel G. Blythe from the pages of the Post

The Hour of Aëroplanes

By F.S. Bigelow

Ah, the French esprit. Here is an amusing example of the bright, happy spirit of the French in the early days of the war, before thousands of deaths darkened the country’s mood.

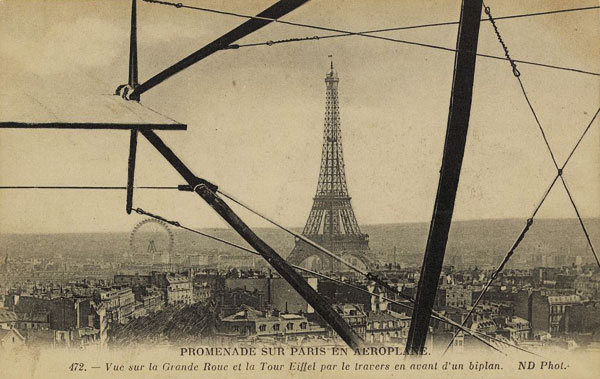

“In a single week this became a veritable institution. At half past four, or perhaps at five, the planes began to appear. Suddenly the streets swarmed with people who wanted to see them. The Place de l’Opéra may fairly be said to be the center of Parisian sidewalk life. Every afternoon this square was closely packed with eager sightseers. When a plane was sighted the crowd in the square set up a shout and the people at the café tables rushed into the street to get a better view. Much of the talk was of bombs, planes, and Zeppelins.

“By no means were all the aircraft that passed over the city hostile. Indeed, most of them were French scouts; still, it took two looks to distinguish friend from foe. … The simplest rule is that friends fly low and foes remain aloft out of danger.

“There is no doubt the first bomb-dropping foray made the city nervous; but Paris made a fête of it, nevertheless. Army officers sitting at sidewalk café tables rushed into the streets and discharged their revolvers at the aerial enemy, quite regard-less of the fact that he was far out of range. Still, the shooting was fun and it added to the excitement. The higher military authorities, not to be outdone, mounted ma-chine guns on the public buildings and took futile pot shots at the gun-shy strangers.

“Before a week had passed the Hour of Aëroplanes had become such an institution that old men, bearing hand bags full of opera glasses, were wending their way among the sidewalk tables, renting their glasses to those who wished a better view.

“When a plane was sighted it was almost a point of café etiquette to warn your companion to raise her lilac parasol to keep off the bombs. If your careless neighbor, rising hastily, overturned your little table and sent a carafe of water or a siphon of soda crashing to the sidewalk, the delighted crowd exclaimed, ‘A bomb ! A bomb!’ and showed every sign of glee while the waiter was sweeping up the broken glass.”

The Wreck of a Continent

By Samuel G. Blythe

Europe’s collision with war reminded Blythe of the days that followed the Titanic’s collision with an iceberg. Now, as England began shaking off its shock and disbelief, it was handing unprecedented powers over to its wartime government.

“I sat in the visitors’ gallery of the House of Commons a few afternoons ago and heard the legislators there passing law after law of the most sumptuary character, without sword of debate, without question, without a protest of any kind. Measure after measure came up and was hurried through on that afternoon, and on other afternoons, placing the control of the people of England — the absolute control — in the hands of the Privy Council and the military and the naval authorities, which are the state; for by the passing of these acts the Parliament voted itself subordinate to the men who are thus empowered to act. Parliament abrogated many of its own functions, recognized the emergency, and placed itself in un-questioning obedience to the supreme power.”

The Unemotional Frenchman: A Wartime Trip Through the Southern Provinces

By Homer Saint-Gaudens

Homer Saint-Gaudens, son of the famous American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, found himself stranded in a French town also named Saint Gaudens when the war broke out. His two-part article showed the French quietly resigning themselves to war.

“Here had been a perfect opportunity for flags, confusion, illogical demands on the government, irresponsible moves by the government, extras, scareheads, and patriotic drunkenness. Yet none of these appeared. When the call came each man heaved a sigh of regret, laid down his tools and stood ready. The government was of his choosing. It had prepared the country for the crisis before it. He had infinite faith that all measures had been taken for the national safety. What these were he did not know. Were he to know everybody would know, the country’s enemies would know. His task was to obey the call to arms. He did not complain or criticize.

“The roads we found deserted of teams, the fields deserted of laborers. In the doorways stood women. Toward the railroad station moved a young man and a girl. The man had a bundle in one hand, the other was on the girl’s shoulder. From the station came three girls walking quickly up the road, hand in hand, crying. Only women came from the stations. One and all were dressed in black—most of them had been weeping. More and more we became the unwilling witnesses of other persons’ domestic tragedies.

“We had seen recruits before, mostly huddled together like cattle driven to the slaughter. We had heard the Marseillaise sung before, especially in that maudlin fashion in Saint-Gaudens. These men were neither cattle nor maudlin. They were unkempt and they perspired. They were dirty. They smelled of garlic and their bundles were awry. But they were sober, and they were proud as they passed up the hot, sunlit street; and they sang the song of their land and marched it as their fathers must have marched and sung it when first it was written.”

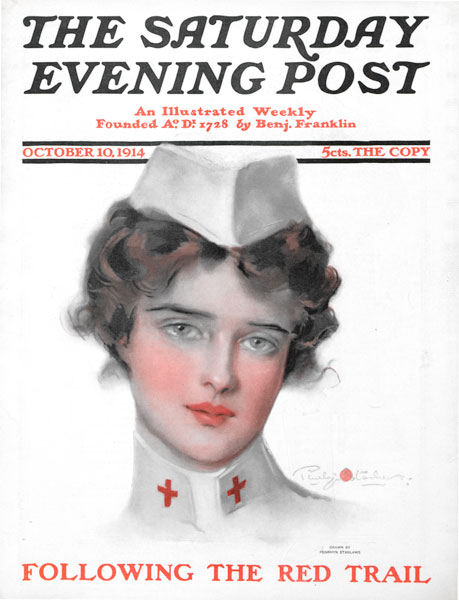

Following the Red Trail: The Real Perils of War

By Woods Hutchinson

A professor of clinical medicine and a medical writer, Hutchinson was optimistic that modern medicine would help control the casualty numbers of the war. Combat deaths declined in every successive war, he noted, and he expected they would remain low in the coming months.

“The cheerful pastime of slaughtering our fellow men has, in the most recent wars, been carried on with smaller loss of life and less suffering and hardship, both to the actual combatants and to the noncombatants in whose territories the war is waged.

“The average death rate of the first three great wars of the past century — the Napoleonic, the Mexican, and Crimean — was 12.5 percent a year; that of the last three wars — the Spanish-American, the Boer, and Russo-Japanese — was 4.8 percent.

“By the time the Napoleonic wars were reached, the mortality from deaths in war, from all causes, had fallen to about 125,000 a year, or about 12 percent.

“In our own Civil War, it fell to 10 percent.

“The Sedan campaign cost the German army only 8 percent of its three-quarters of a million men; while our Spanish-American and England’s Boer War reached the low-water mark, with barely 3 and 4 percent of loss respectively.

“As to the cause of this gratifying reduction in war fatalities, several influences have been at work. One of the most obvious has been that the invention of gunpowder and the improvements of rifles and artillery, with such enormous increase in their range of death dealing, has steadily forced more and more of the fighting to be carried on at long range.

“The net result of this has been that not nearly so many men are actually hit as in the days of old point-blank firing by platoons; that as a battle becomes a long-range duel … its fate is decided more and more by maneuvers such as surrounding a force or cutting it off from its base than by actual sacrifice of life, or by weight of numbers in a bayonet charge.

“The other most important change … was that in the old days, when battles were decided by hand-to-hand fighting, the victors were literally right on top of the vanquished the moment the tide turned and the retreat began; and only superior fleetness of foot or length of wind could save a very large percentage of the beaten troops from slaughter, maiming, or slavery.”

Despite Hutchinson’s predictions, the First World War quickly surpassed single-digit casualty rates. The percentage of casualties in Great Britain’s forces was 36 percent. It was 65 percent for Germany, 76 percent for Russia, and 90 percent for Austria-Hungary. (The casualty rate for American forces, which were engaged for only 17 months, was 7percent.)

Step into 1914 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post 100 years ago.