Healthy Weight, Healthy Mind: How Important Is Exercise for Weight Loss?

We are pleased to bring you this regular column by Dr. David Creel, a licensed psychologist, certified clinical exercise physiologist and registered dietitian. He is also credentialed as a certified diabetes educator and the author of A Size That Fits: Lose Weight and Keep it off, One Thought at a Time (NorLightsPress, 2017). See all of David Creel’s articles here.

Here’s a story I’ve heard many times.

I hired a trainer I saw once a week for two months. I endured grueling workouts and was pretty faithful about working out on my own several times per week. I felt great, my endurance improved, and I could hold a plank for two minutes. But I only lost two pounds. Six-hundred dollars for two pounds! It doesn’t seem fair, nor does it make sense.

I agree this doesn’t seem fair. After all, when we work hard we want results. However, if we think about it logically, the results do make sense. Compared to making dietary changes, the short-term weight loss we experience from moderate exercise is modest at best.

Shantell is a good example. She reluctantly told me she drank approximately 12 regular sodas per day. Not counting french fries, she hadn’t consumed a vegetable in weeks. She and her kids ate fast food almost every day, and the meals she prepared at home included bologna sandwiches, hot dogs, or fish sticks. She would round out her meals with macaroni and cheese, potato chips, or tortilla chips. Although she didn’t eat a large volume of food, her diet needed a major overhaul.

Instead of trying to change everything at once, we focused on simply decreasing her soda consumption.

To my amazement, after our meeting she totally stopped drinking the ten-teaspoons-of-sugar-per-can stuff. When she returned a month later, she had lost 16 pounds. She didn’t make other changes in her eating, just the soda. If we assume Shantell consumed the same number of calories she was burning at the time we first met (her weight was stable), any calorie reduction would lead to weight loss. Table 2 illustrates how decreasing her consumption of soda (a total of 1800 calories per day) could lead to almost 16 pounds of weight loss in a month. Remember, burning 3500 calories more than we absorb equates to one pound of weight loss. So the math makes sense. Although Shantell’s diet still needed a lot of work, she was able to lose significant weight with only one change in her diet.

Now let’s look at how much exercise Shantell would need to do in order to lose a similar amount of weight. She weighed about 350 pounds, so walking burned more calories for her than for someone who weighed less and walked at the same speed. Think of it this way: The more someone weighs, the more work they do when moving that weight a given distance. For example, walking a mile with a 40-pound backpack requires more calories than walking a mile without it. In addition, because of her excess weight, Shantell’s resting metabolism was higher than an average-weight woman. I estimated she burned about two calories per minute simply sitting still. Table 3 shows Shantell would burn approximately 140 net calories per mile and would need to walk about 13 miles per day to burn the same number of calories she saved by not drinking 12 cans of soda. At two miles per hour, that would be almost 6½ hours of walking each day!

If you don’t drink 12 sodas per day, this example may seem a little extreme. But even if your extra 500 calories come from late night grazing, you’ll find it hard to “undo” those dietary indiscretions with physical activity. The point of these math gymnastics is to demonstrate that burning calories through exercise is generally more difficult than saving calories by eating differently.

This is especially true for people who can only exercise at low intensity. An elite runner can burn a lot of calories during an hour of exercise, whereas someone taking a slow walk burns far fewer calories. The runner may cover ten miles during that hour, while the overweight person walks two miles an hour. Many studies back up this principle of diet-versus-exercise for weight loss. We know that, in the short run, exercise doesn’t directly cause much weight loss. When we look at the long run, it’s an entirely different story.

| Diet Induced Weight Loss | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Diet Change | Calorie Savings per Day | Calorie Savings per Month | 30-Day Weight Loss |

| Stopped drinking 12 sodas/day | 12 sodas x 150 calories each = 1800 calories | 1800 calories x 30 days = 54,000 | 54,000 cals/3500 = 15.5 pounds |

| Walking Time Required to Lose 15.5 pounds in One Month | ||

|---|---|---|

| Extra Calories Burned/Mile | Miles of Walking to = 1800 Calories | Time required to walk 12.8 miles at 2 mph |

| 200 calories per mile – 60 calories burned at rest = 140 net calories | 1800 calories/140 calories per mile = 12.8 miles | 12.8 miles @ 2mph = 6.4 hours |

In order to understand long-term weight loss success, researchers study people who are good at it. Many studies show that people who lose weight and keep it off are

physically active. Data from the National Weight Control Registry and many studies conducted by Dr. John Jakicic at the University of Pittsburgh tell us that exercise is a crucial component in keeping lost weight from reappearing. Although studies vary on exactly how much exercise is necessary to keep weight off, most experts agree that engaging in 250 to 300 minutes of exercise each week will greatly increase your chances for success.

You may wonder why short-term weight loss from exercise tends to be modest, yet exercise is almost a requirement if you want to prevent weight regain. Researchers have not yet conclusively demonstrated why exercise is related to long-term success in weight loss. Although exercise, especially resistance training, may help prevent muscle loss and a lowering of metabolic rate that accompanies weight loss, not all studies support this idea. But when we look at the many other benefits of physical activity, we can draw logical conclusions about the long-term benefits of exercise.

- The longer we stick with an exercise routine, the more fit we become. As we become more fit we’re able to increase our exercise intensity for longer periods of time. The more we can do, the more calories we burn. When we’re feeling fit we gravitate toward physically challenging things that burn more calories.

- Exercise improves mood. If we feel less depressed and anxious we’re less likely to eat emotionally or be distracted from personal health goals.

- While exercising, we are not sitting in front of the TV. If we aren’t sitting in front of the TV, we can’t be eating in front of the TV.

- If we invest in our bodies by taking time to do good things for them, we probably don’t want to abuse the body with unhealthy eating. That would be like intentionally driving through the mud after a car wash.

- For those who enjoy physical competitions with themselves or others, eating is fuel for those endeavors. If high octane (healthy food) is available, we use it.

- Feeling accomplished about physical activity can improve confidence in other areas, including wise choices in what and how much we eat.

Come back each week for more healthy weight loss advice from Dr. David Creel.

Healthy Weight, Healthy Mind: Tips for Eating Smart, Part 2

We are pleased to bring you this regular column by Dr. David Creel, a licensed psychologist, certified clinical exercise physiologist and registered dietitian. He is also credentialed as a certified diabetes educator and the author of A Size That Fits: Lose Weight and Keep it off, One Thought at a Time (NorLightsPress, 2017). See all of David Creel’s articles here.

Last week I offered four eating tips to help you lose weight and keep it off in a healthy manner. Here are three more helpful hints to help you manage calories and develop sound eating habits.

5. Choose Whole Grains

Our bodies like to operate on sugar (glucose), especially when we exercise at high intensities. When we eat whole grains, complex carbohydrates break down and sugar slowly enters our bloodstream, ready for use by our brain and working muscles. Whole grain foods such as wheat bread, brown rice, quinoa, and oats are rich in vitamins and minerals as well as fiber. Whole grains can be slightly higher in calories, which you will see if you compare white bread to whole wheat bread, because they contain the germ of the seed — a source of healthy fat. Despite the slightly higher calories, you’ll probably feel fuller longer because the whole grain fiber slows the rate at which food empties from the stomach. In addition, many foods made with refined grains (crackers, muffins, pastries, cookies, etc.) have added fats and sugars that boost the calorie count and increase our drive to overeat them.

6. Eat Lean Protein at Meals and Snacks

Calorie-for-calorie, protein tends to be more satiating than fat or carbohydrates. If I asked you to rate your fullness after eating 300 calories of pasta with red sauce (carbohydrates) versus the same calories worth of cheesecake (a tiny piece loaded with fat), compared to boneless skinless chicken breast (almost entirely protein), which would fill you up the most? Studies show it would be the chicken breast. Protein is important to help us feel satisfied after eating. Thus, adding an egg to your breakfast or a low-fat cheese stick to your afternoon snack may help curb overeating later in the day.

7. Watch for Hidden Fat

For several summers during college I worked breakfast and lunch room service in a high-end hotel. Each morning, dressed in my white Oxford shirt, black pants, and bow tie, I would grab something quick to eat between orders. Oatmeal was my favorite. I wasn’t sure why, but this was the best oatmeal ever. I thought maybe the hotel ordered exotic oats from overseas, which would explain the silky texture and rich flavor. Each morning I scarfed down a bowl or two of what I thought was the healthiest thing I could get my hands on. One morning I happened to enter the kitchen when Ms. B, as we called her, was making a large batch of the good stuff. Ms. B was a sweet black lady from Alabama who called everyone Honey. She seemed to cook from the depths of her soul and her food tasted better because you know she prepared it just for you. I can only imagine she learned to cook from her mother, who learned to cook from her mother.

Having family from the South, I knew all about the fat-is-flavor style of cooking. But I couldn’t believe my eyes when I walked in on Ms. B mid-oatmeal and saw her pouring a large carton of half-and-half creamer into the oats. I never imagined someone could do that to oatmeal! That day I learned a valuable lesson about hidden fat, especially when dining out. People often underestimate the calories in food because they don’t account for added fat, especially when others prepare it. Remember, one gram of fat has nine calories. A teaspoon of butter contains about four grams of fat or 36 calories. A stick of butter has over 800 calories (think cookies), compared to an equally sized banana of around 90 calories.

Follow This Diet

In summary, there is no best diet for weight loss and weight loss maintenance. But consuming a diet that’s rich in vegetables, lean protein sources, fruits, whole grains, and low-fat dairy will make weight loss more likely and give you the best chance of preventing diet-related diseases. In addition, eating a balanced diet can make you feel more energetic and give you the fuel to exercise consistently.

Come back each week for more healthy weight loss advice from Dr. David Creel.

Weight Loss Advice from the 1930s: Eat Less, Exercise More

Topping most of our resolutions this year is a repeat from the past: weight loss. But who’s to blame for this obsessive desire to trim and slim our figure? Automation? Hollywood? Feminism? France? Here’s a 1934 doctor’s take on America’s ongoing weight-loss craze:

—

Pounding Away

Originally published in The Saturday Evening Post, September 22, 1934

Before the establishing our modern knowledge of diet, it was taken for granted that the shape anyone might have had been conferred upon him by providence, and the best one could do would be to make the most of it. There was little to be done in making the least of it. Nature creates human beings and animals in all sorts of forms and sizes. A Great Dane takes many a roll in the dust, but never achieves the slimness of a greyhound; a draft horse of the Percheron type travels many a mile pulling heavy loads, but never gets small enough to be a baby’s pony. Nevertheless, the basic framework can be modified as to the amount of upholstery. Every woman knows that she can, by suitable modification of her diet and by the use of proper exercise, cause the pounds to pass away.

No one has determined certainly the cause of the recent craze for reduction. Perhaps it was the outgrowth of criticism of the female figure that was popular in the late ’90s. The textbooks of the ’90s had much to say about corset livers and hourglass shapes. The preference for the boyish form may have been the result of the gradual change in the amount of clothing worn by women. The multiple petticoats and the heavy underclothing of the late ’90s began to give way to single garments in what was called the empire style. The styles have tended toward the slim figure, covered by less and less clothing. Perhaps the change was the result of the coming of the automobile; that, too, has been a most significant factor in the change of our body weight.

A Matter of Form

Walking, up to 1900, was the accepted mode of transport for the human body in the vast majority of circumstances. Then came the motor car. Today there is in this country one motor car for each five persons, and walking is gradually becoming a lost art. Walking used to be the form of exercise primarily responsible for burning up the excess intake of food. With the gradual elimination of walking and with the coming of the machine in industry, there has been less and less demand for energy in food consumption and more and more tendency toward maintaining a slim figure by a reduction in the consumption of food. The person who takes no exercise and who eats the diet that was prevalent from 1900 to 1905 will put on weight like an Iowa hog in training for a state fair.

The suggestion has even been made that feminism was responsible for increasing the popularity of women like men. Within the last quarter century more and more women have come out of the home and into various clerical, manufacturing, promotional, industrial, and statesmanlike occupations. No doubt, the bobbing of the hair and the binding and suppression of the breasts, as well as the thinning of the figure and simplification of the costume, were women’s response to the necessity for greater ease of movement and less encumbrance while engaged in such work. A fat girl gets lots of bumps from office furniture in modern designs.

Then came the war, and with it there was intensification of all these motivations; the war made serious demands on women. The slightly suppressed desires for freedom merged into strong impulses and urges that suddenly seized every feminine mind. What had been merely a somewhat languid interest suddenly became a dominating craving. Reducing became the topic of the hour, and the craze for reduction was upon us.

It has been urged by some that the final stimulus for slenderness was a sudden change in fashions promoted by the modistes of France. Be that as it may, the French women themselves never succumbed to the craze for emaciation as did their American sisters.

The French are far too sound a race from the point of view of feminine psychology to urge the cultivation of manly traits in their women. No doubt, the French fashions did incline toward women of somewhat thinner type, but the modistes did not, like our designers of costumes, adopt an all-or-nothing policy. Individualization in form and costume has more often been the mark of France, whereas standartization and uniformity have dominated the American scene.

American manufacturers of ready-made clothing, with the beginning of the 1920s, began to produce models for slim women, hipless and bustless. As the women went into the department stores to purchase, they found it difficult to obtain anything that would fit. They came out wringing their hands and crying that most famous of all feminine laments, “I can’t get a thing to fit me.” And when a woman cannot get a thing that will fit, she is ready to fix herself to fit what she can get. There were promptly plenty of experts ready to help her through the fixing process.

To Make the Person Personable

Advertisements began to appear of nostrums to speed the activity of the body and to lessen its absorption of food. Phonograph records were sold, giving explicit instructions regarding exercise and diets. The radio poured forth systematic calisthenics and played tunes for the performance of these motions in a rhythmical manner. Plaster fell from many a living-room ceiling while women of copious avoirdupois rolled heavily on the bedroom floor. The springs and frames of many a bed groaned wearily beneath the somersaults of some damsel of 170 pounds. Pugilists who had been smacked into insensibility on the rosined floors of the squared rings became heavily priced consultants for ladies of fashion and of leisure who embarked on programs of weightlifting: Department stores offered, in the sections devoted to cosmetics, strangely distorted rolling pins with which it was claimed fat might be better distributed about the person. Shakers, vibrators, thumpers, bumpers, and rubbers manipulated electrically, by water power, or even by gas, were offered to those who cared to try them.

Out of this turmoil came a demand for a scientific study of overweight, its effects on the human body, its relationship to economics, sociology, psychology, happy marriage, the maintenance of the home, and physical and mental health. In response to this demand, research organizations in many medical institutions began to study the factors responsible for obesity and the most suitable methods for overcoming the condition without injuring the general health. Whereas, in scientific medical indexes of a previous decade, an occasional article only might be devoted to this subject, the indexes of recent years show scores of records and reports in this field.

The Do-or-Diet Spirit

The first response to the craze for reduction, as I have said, was the development of extraordinary systems of exercise, with the idea that a woman could keep right on eating the same amount of food that she formerly took and that she could get rid of the effects of this food by excessive muscular activity. Quite soon the women found out the error of this notion.

Walking 5 miles, playing 18 holes of golf, or even 6 active sets of tennis does not use up enough energy to take off any considerable amount of weight. Even the playing of an excessively severe football game removes from the body relatively little tissue. A football player, it has been reported, may be found to weigh from 5 to 10 pounds less after a football game than he weighed before, but most of this loss of weight is merely due to removal of water from the body, which is promptly restored by the drinking of water after the contest is over. Actually, the terrific strain of one hour of football burns up not more than one-third of a pound of body tissue.

Thus reduction of weight is for most people simply a matter of mathematics, calculating the amount of food taken in against the amount used up. Reduction is a matter of months and years, not of days. The investigators have shown that it is dangerous for the vast majority of people to lose more than two pounds a week. A greater loss than this places such a strain on the organs of elimination and on tissue repair that its effects on the human body may be serious and lasting.

When women found that weight could not be permanently removed to any considerable extent by excess exercise, they began to try extraordinary diets. The diets first adopted were selections of single elements. They have been characterized as perpendicular rather than horizontal reductions. The phrase refers to the nature of the diet rather than to the effect on the human form. In a perpendicular diet, the partaker eliminates everything except one or two food substances and limits himself exclusively to these. In a horizontal diet, one continues to eat a wide variety of substances, but eats only one-half or one-third as much of each. Perpendicular diets are dangerous because they do not provide essential proteins, vitamins, and mineral salts. These will be found in a properly chosen diet which includes many different foods, but smaller amounts of each. So women began eating a veal chop alone, pineapple alone, hard-boiled eggs alone, or lettuce alone. The phrase “let us alone” best expresses the proper attitude to assume toward a woman on a perpendicular diet. The constant craving for food and the associated irritability make the woman on such a diet a suitable companion only for herself, and sometimes not even for that. Certainly, she is no pleasure around a home. Among the first of the books of advice to be published on diet was one concerned only with the calories. No doubt, successful reduction of weight was easily accomplished by the caloric method, but the associated weakness, illness, and craving for food soon brought realization that there was more to scientific diet than merely lowering the calories.

The next extraordinary manifestation was the 18-day diet from Hollywood. The exact origin of this combination does not appear to be known. Perhaps it appeared first in print in the columns of criticism of motion pictures of a well-known Hollywood writer. In her statements on the subject, it was said that the diet was the result of five years of study by French and American physicians, and that the diet would be perfectly harmless for those in normal health. If the French and American doctors spent five years working out the 18-day diet, they wasted a lot of time. Any good American dietitian could have figured out an equally good combination, and probably a much better one, in an afternoon. The vogue of the 18-day diet was phenomenal. Restaurants and hotels featured it in their announcements. Hostesses, anxious to please their dinner guests, called each of them by telephone to know which day of the 18-day diet they had reached and served each guest with the material scheduled for that particular meal. It was said that a Chicago butcher bragged that he had eaten the first nine days for breakfast.

The 18-Day Sentence

The 18-day diet had peculiar psychologic appeal. For the first few days it consisted primarily of grapefruit, orange, egg, and Melba toast. Melba toast, be it said, is a piece of white bread reduced to its smallest possible proportions; then dried and toasted so as to be developed into something that can be chewed. By the second or third day, when the participant had reached the point of acute starvation, she was allowed to gaze briefly on a small piece of steak or a lamb chop from which the fat had been trimmed. Then two or three days of the restricted program followed, and again, when the desire for food reached the breaking point, a small piece of fish, chicken, or steak could be tried. Thus the addict passed the 18 days, during which she lost some 18 pounds. Then, pleased with her svelte lines, she began to eat; three weeks later she could be found at the point from which she had first departed.

For years it has been recognized that human beings need magical stimuli in the form of amulets, powders, or charms to aid in the concentration necessary for success in love, religion, health, or business. The human mind needs some single object to which it may pin its hopes, its faiths, and its aspirations. Moreover, there was the psychological appeal of mob action. There was the desire to be doing what everybody else was doing at the same time. Then there was the thrill of competition. One could hear the addicts of the Hollywood diet asking one another, “What day are you on?” And the answer came back, “I’m on the tenth day and I’ve lost eight pounds.”

With the mystic appeal of Hollywood, land of mystery, with the psychological understanding of human appetite, with the introduction of the Melba toast, the Hollywood diet swept the nation.

The Calorie Gauge

The one thing necessary to reduce weight successfully in the majority of cases is to realize just how many calories are necessary to sustain the life of the person concerned and what the essential substances are that need to be associated with those calories. Most of us enjoy our food. We eat food because we like it, and we eat without thinking what the food will do in the way of depositing fat. The researches in the scientific laboratories that have been made in the past 10 years indicate that we eat more food than we need, particularly at a time when energy consumption is far less than energy production. It has been generally assumed that the weight of the body is definitely related to health. There are standard tables of height and weight at different ages for all of us from birth to death. It must be remembered, however, that these are just averages and that any variation within 10 pounds or even 15 pounds of these averages is not incompatible with the best of health in a person who inclines to be either heavy or light in weight as a result of his constitution and heredity.

There are two types of overweight: One … in which the glands of internal secretion fail to function properly; the other … due to overeating and insufficient exercise. The glands of the body, including particularly the thyroid, the pituitary, and the sex glands, are related to the disposal of sugars and of fat in the body. In cases in which the action of these glands is deficient, a determination of the basal metabolic rate of the body will yield important information. This determination is a relatively simple matter. One merely goes without breakfast to the office of a physician who has a basal-metabolic machine, or to a hospital, all of which nowadays have these devices. One rests for approximately one hour, then breathes for a few minutes into a tube while the nose is stopped by a pinching device, so that all the air breathed out can be measured. By appropriate calculations, the physician or his technician reaches a figure which represents the rate of chemical action going on in the body. A rate of anywhere from –7 to +7 is considered to be a normal metabolic rate. A rate of anywhere from –12 to +12 may be within the range of the normal for many people. If no other special disturbance is found, the physician is not likely to be concerned about the metabolic rate within such limitations. Rates well beyond these two figures, however, are considered to be an indication of failure in the chemical activities of the body — namely, either too rapid or too slow — and measures should be taken promptly to overcome the difficulty. If the basal metabolic rate is –20, –25 or –30, the physician will prescribe suitable amounts of efficient glandular substances to hasten the activity. Moreover, he will at this time arrange to repeat his study of the metabolic rate at regular intervals. He will watch the pulse rate and the nervous reaction of the person to make certain that the effects of the glandular products that are administered are kept within reasonable limitations. If, on the other hand, the basal metabolic rate is found to be +20, +25, or +30, he will make a study of the thyroid gland and will provide suitable rest, mental hygiene, and possibly drugs to diminish this excess action. Rarely, indeed, is a person with a metabolic rate of +25 fat; in most instances, such people are thin, sometimes to the point of emaciation. There are periods in life when the human body tends to put on fat. As women reach maturity, as they have children, as they approach the period at the end of middle age, there is a special tendency to gain in weight. Men are likely to spend more time in the open air, eat more proteins and less sugar than do women, and therefore are less likely to gain weight early. The common period for the beginning of overweight is between 20 and 40 years of age; in women the average being usually around 30. Among men, the onset of overweight is likely to come on eight to ten years later.

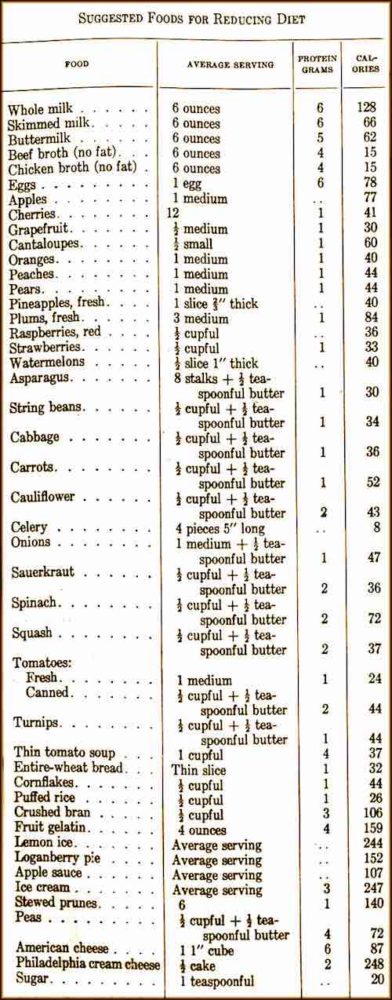

A man doing hard muscular work requires 4,150 calories a day; a moderate worker, 3,400; a desk worker, 2,700, and a person of leisure, 2,400 calories. A child under one year of age requires about 45 calories per pound of body weight, about 900 calories a day. The number is reduced from the age of six to 13 to about 35 calories per pound, or 2,700 a day; from 18 to 25 years, about 25 calories per pound of body weight may be necessary, or 3,800 a day. Thus, a person 30 years old, weighing about 150 pounds, may have 2,700 calories; a person 40 years of age, weighing 150 pounds, may have 2,500 calories; a person 60 years of age, weighing 150 pounds, may have 2,300 calories. A calorie is merely a unit for measuring energy values. In the accompanying table examples are given of the number of calories in various well-established portions of food.

Slim Picking

The overweight child at any age is quite a problem for the doctor. Most times it is the result of a family that tends to eat too much. Children of fat people are likely to be fat because they live under the same conditions as do their parents. If the adults of the family eat too much, the children can hardly be blamed for doing likewise. Investigators at the University. of Michigan say that the normal person has a mechanism which notifies him that he has eaten enough. Obese people require stronger notification before they feel satisfied, and many disregard the warning signal because they get so much pleasure out of eating. “Pigs would live a lot longer if they didn’t make hogs of themselves,” said a Hoosier philosopher.

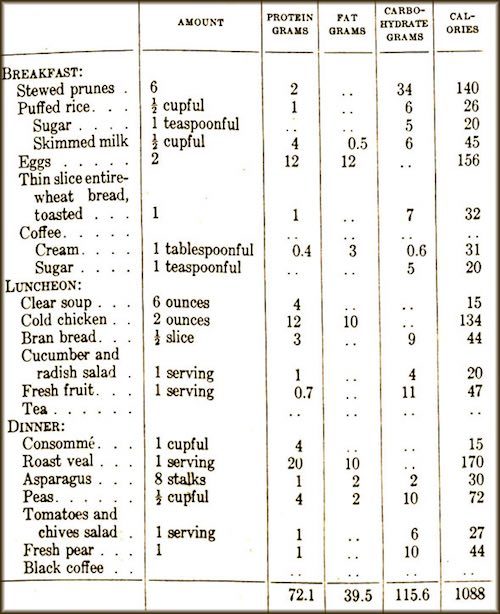

If a physician has determined that excess weight in any person is not due to any deficiency in activity of the glands, but primarily to overeating, it is safe to take a diet that contains a little more than 1,000 calories a day, and that provides all the important ingredients necessary to sustain life and health. A menu like the following, outlined by Miss Geraghty, provides about 1,000 calories as well as suitable proteins, carbohydrates, fats, mineral salts and vitamins:

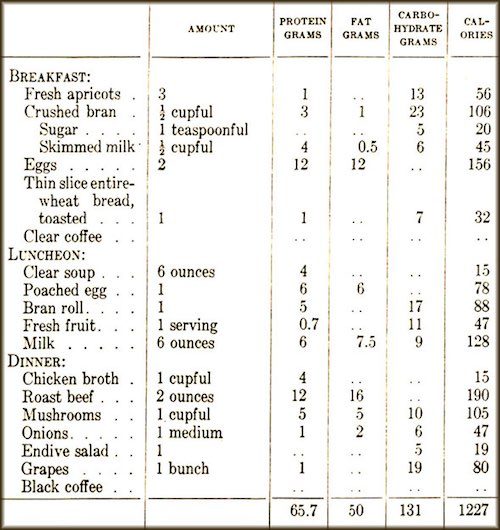

For those who want to reduce intelligently, here is another menu that includes all the important ingredients:

If you simply must have afternoon tea, add in 150 calories that the sugar and accompanying wafers will contain.

Every woman who has heard of these diets insists that they provide about twice as much food as she usually eats. This merely means that she is talking at random rather than mathematically. These diets do contain a wide variety of ingredients, but they are chosen with exact knowledge of what they provide in the way of calories and important food attributes. Quite likely, the women who protest eat a smaller number of food substances, but it is likely, also, that they eat so much of each of these substances that their calories are far beyond the total. Furthermore, they probably fail to keep account of the occasional malted milks, cookies, chocolates, or ice cream that they have taken on the side.

From the accompanying table of caloric values, it is possible to select a widely varied meal that will provide any number of calories deemed to be necessary; and if the meal is selected to include a considerable number of substances, it will have all the important ingredients.

In taking any diet, it is well to remember that calories are not the only measuring stick for food. A pint of milk taken daily provides many important ingredients. If bread, potatoes, butter, cream, sugar, jams, nuts, and various starchy foods are kept at a minimum, weight reduction will be helped greatly.

Over the radio and in a few periodicals that do not censor their advertising as carefully as they might, there continue to appear claims for all sorts of quack reducing methods. If only most people had some understanding of the elementary facts of digestion and nutrition, the promotion of such methods would yield far fewer shekels to the promoters. It is a simple matter to get rid of excess poundage and, in general, it is quite desirable. One merely finds out first how many calories per day constitute the normal intake, and tries to get some idea of the number necessary to meet the demands of the body for energy. One selects a diet which provides the essential substances and which permits some 500 to 1,000 calories less per day than the amount required.

Under such a regimen, steadily persisted in, the fat will depart from many of the places where it has been deposited, but not always from the places where it is most unsightly. For this purpose, special exercises, massage, and similar routines may be helpful. But persistence more than anything else is required. It is just a matter of pounding away.

Lose Weight for Good!

Becoming happier, saving more money, falling in love, and spending more time reading are all perennial favorites among Americans’ New Year’s resolutions. But year after year—according to online polls and other surveys—the number one spot remains the same: losing weight. If you’re an optimist, you might interpret that as a sign that we’re facing up to the national obesity epidemic; 68 percent of U.S. adults are overweight or obese. But if you’re a realist, you may see the unending quest for weight loss differently—as evidence that shedding pounds and keeping them off seems to be harder than growing a third arm.

Why? Or, as anyone who has tried and tried but failed and failed to permanently slim down might put it, “Why??!!” If you read the testimonials from people who lost 50, 100, or more pounds on a commercial diet or the seemingly sure-fire advice from health magazines (eat pistachios! try grapefruit!), losing weight is easy. But here’s the irony: There are almost as many ways to successfully lose weight as there are people who need to do so.

To name but a few examples, drinking lots of water does make you feel fuller and therefore likely to eat less. (In one study, drinking 16 ounces of water before a meal led to 5 extra pounds of weight loss after 12 weeks—people felt too full to eat more.) Eating soup for dinner does, indeed, fill you up (again, with water), making it easier to eat less. Covering two-thirds of your plate with vegetables (no cream sauce!) leaves less room for calorie-laden meats and starches, reducing caloric intake. Cutting out booze, sugar- or fat-laden drinks (that includes lattes), potato chips, baked desserts—you know the list—does help. But knowing what works and doing what works are two different things.

Just in time for 2012, research is finally addressing the “doing” part. From psychological tactics such as exploiting the power of groups to a new understanding of metabolism, science has more to offer dieters than ever before, providing guidance about which diet and exercise regimens offer the best chance to help you lose weight and become fitter.

Take the most fundamental of dieting basics: that weight drops when and only when the number of calories you burn exceeds the number you take in. Experts now recognize that both sides of the energy/balance equation—calories burned and calories consumed—are not as simple as how much you exercise and how many calories are in the food that passes your lips. “The conventional thinking about calories in/calories out is changing, as research shows that people have different reactions to different macronutrients,” says Dr. Richard Kreider, professor of health and kinesiology at Texas A&M University. “That’s why no one diet or exercise plan works for every individual. If everyone cut their intake 500 calories a day and exercised an hour more, it would have different effects on different people.”

Let’s start with calories burned. Don’t be discouraged by the paltry number you burn during exercise (for a 160-pound person, 288 calories in a leisurely one-hour bike ride, for example, or 317 in a one-hour walk at 3 miles per hour—in both cases, barely enough to burn off a couple of scrambled eggs on unbuttered toast). Instead, emphasize the kind of exercise that can increase your metabolism so you burn more calories doing “nothing.” Fidgety people tend to be slimmer; burning extra calories for, say, 16 hours per waking day, seven days a week, adds up to more than you get by brief and sporadic bursts of exercise. That doesn’t mean we should all start fidgeting. But the basic principle means that it helps to incorporate resistance (or strength) training into your regimen. Leg lifts, situps, squats, and the like build muscle, notes Kreider. A pound of muscle burns more calories than a pound of fat. Therefore, replacing fat with muscle will raise your baseline metabolism. “You burn more calories after your workout as well as during,” Kreider says.

Slashing your caloric intake, on the other hand, lowers baseline metabolism. This is why so many people are yo-yo dieters. They shed pounds by limiting their calories to, say, 1,200 a day, but because very low-calorie diets tend to take off muscle (in many cases, half or more of the lost pounds are muscle) the result is an increasingly lower metabolism. Eventually it gets so low, says Kreider, that you have to practically starve yourself to keep from gaining weight.

Starving yourself is not fun, in case you hadn’t noticed. And being miserable on a diet is also a big reason people give up, setting the stage for next year’s New Year’s resolution. Very low-cal diets can trip you up for another reason. A study published online last September in The Journal of Clinical Investigation found that when glucose levels drop, as happens when we consume too little, the brain’s hypothalamus senses the change and activates the brain’s insula and striatum, which are associated with reward, inducing a desire to eat. At the same time, the prefrontal cortex seems to lose its ability to put the brakes upon the “EAT! EAT!” signals coming from the striatum. That impairs the ability to inhibit the impulse to eat when glucose levels plunge, explained Dr. Kathleen Page of the University of Southern California, who led the study.

Different foods can raise or lower your baseline metabolism. To lose weight, you want more of the former without compromising nutrition. Green tea and caffeine raise baseline metabolism. And because muscle burns more calories than fat, foods that build muscle—namely, those high in protein—will indirectly raise your metabolism just as resistance training does. Calories from protein also take more calorie-burning energy to digest and leave you feeling fuller than calories from carbohydrates. High-fiber grains are a close second followed by fruits and vegetables with starches and sugars trailing badly. If a diet leaves you feeling full, you are more likely to stick to it, making it a true lifestyle change and not an eight-week crash program. The realization that foods differ in how full they leave you led Weight Watchers to revamp its famous points system a year ago. A PB&J on white bread with chips sets you back 11 points, but so does a heaping Greek salad, soup, pasta, and grapes, which is much more filling. The idea is to use your points on foods like the latter.

The protein effect helps explain why, in a 2011 Consumer Reports analysis, Jenny Craig, Slim-Fast, and Weight Watchers were all good to excellent at both short- and long-term weight loss and adherence (Jenny Craig came out on top). These diets are effective because they get 20 percent or more of calories from protein (experts suggest going as high as 30 percent) and include at least 21 grams of fiber for every 1,000 calories. How much of a difference can protein and resistance training make? Kreider put patients on a 2,600-calorie-a-day regimen—800 more than they’d been on during an earlier weight-loss diet—plus exercise. They had very low resting metabolisms, probably a result of their low energy intake. But the patients lost weight on the higher-cal diet; its higher protein content and resistance training built muscle and raised baseline metabolism. “Higher protein intake can also lead to changes in gene expression that make you burn fat more effectively,” says Kreider. It never hurts to have your DNA on board.

One reason Jenny Craig edged its competitors is that it offers single-serving entrees, desserts, and snacks (1,315 calories a day), removing the element of choice. That may sound restrictive, but many dieters are relieved to outsource such decisions. “They’re very effective for some people,” says Dr. John Foreyt, a professor at Baylor College of Medicine and director of its Behavioral Medicine Research Center. In fact, “some people” seems to be “many people.” Strictly prescribed plans tend to have lower drop-out rates both long-term (one year or more) and short-term (less than six months), Consumer Reports found.

On a structured eating plan you are also less likely to eat anything actively bad for you such as foods containing high fructose corn syrup (HFCS). Here is another example of how not all calories are created equal. Although HFCS has no more calories than other sugars, its effect on the brain and body seem to be different, says Dr. Richard Shriner, director of the eating orders and obesity program at the University of Florida, Gainesville. It reduces levels of leptin, the appetite hormone that signals us that we’re full. Shriner calls HFCS a “bariatric food”—a food that alters our physiology in a way that promotes more weight gain than its calorie count would indicate.

The most important factor in whether you will lose weight on a diet is whether you can stay on it. That may partly explain the edge that low-carb diets have over low-fat diets. Low-fat diets are necessarily lower-protein diets because most proteins (meat, dairy, nuts) come with fat. “A low-fat diet is like eating cardboard,” says Foreyt. “You feel hungry and unhappy. For long-term success, a diet has to be tailored to your likes and dislikes.”

Foreyt’s statement is supported by a 2010 study in the New England Journal of Medicine in which fewer people on high-protein diets (like Atkins) dropped out than on low-protein-high-carb diets (26 percent vs. 37 percent).

Exercise plays a role in adherence, too. It promotes a sense of well-being thanks to its ability to raise levels of endorphins and other feel-good chemicals in the brain. “And if you feel better about yourself, you’re more likely to stick to a diet,” says Foreyt. That said, it’s just about impossible to lose weight by ramping up physical activity if you don’t change what you eat. A 2011 analysis of 14 exercise studies, which included 1,847 overweight patients, with aerobic exercise programs ranging from 12 weeks to 12 months found an average weight loss of 3.5 pounds after six months and 3.7 pounds after 12. Or as the scientists from McGill University in Montreal concluded, “isolated aerobic exercise is not an effective weight loss therapy.” For exercise to help, it must be “in conjunction with diets.”

The realization that many diets work as long as people stick to them, and that what matters for any individual is whether he or she can do that, has led weight-loss experts to recognize the crucial role that psychology plays in efforts to slim down. Jenny Craig offers counseling sessions, and Weight Watchers has weekly meetings. Curves offers 30-minute structured resistance and aerobic exercise workouts—30 minutes, 500 calories, plus residual metabolism increase. The importance of exercise to build metabolism-raising muscle as well as burn calories means that social support making you more likely to work out can mean the difference between success and failure. “If you want to lose weight, don’t go it alone, especially for exercise,” says Kreider. Try a buddy system. “Trying to lose weight can be a very lonely experience,” says Shriner. “When you’re staring at the fridge at 2 a.m. and are about to binge, have a friend you can call.”

Research has now focused in on what other kinds of psychological support are most helpful, and the winner so far is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). In this approach, which has also proven effective in mental illnesses such as depression, a therapist helps people recognize the negative thoughts that may be keeping them from losing weight, especially the idea that having failed before (as is true for most dieters) means they will fail again. CBT “helps make people aware of what they are telling themselves, especially in the aftermath of a multitude of previous failures,” says Brent Van Dorsten, a clinical health psychologist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Denver. A 2005 review of 36 studies with 3,595 participants by the Cochrane Collaboration, an international group of scientific and medical experts, found that CBT “significantly improved the success of weight loss” compared to diet and exercise alone. “We now have years of research showing that cognitive and behavioral components make a real difference in weight-loss programs,” says Van Dorsten. “When therapists help you set a realistic and clearly defined weight-loss goal, combine several dietary and physical activity strategies, and keep you from catastrophizing”—that is, concluding from one slip-up at the dessert table that you are doomed to fail again—“all of these improve long-term weight loss.”

The use of CBT is part of a sea change in the science of weight loss, which recognizes that what happens inside your skull is as important as what happens inside your digestive system. For instance, a 2011 study by scientists at Yale found that when people thought of a food (in this case, a milk shake) as rich, indulgent, and loaded with calories, after drinking it people’s levels of the hunger hormone ghrelin fell off a cliff; they couldn’t eat another bite. But when people thought of the same food as low-cal and “sensible,” their ghrelin levels hardly budged after they drank it; they were still hungry. That offers another explanation of why “diet” foods don’t work—we think they’re about as filling as a carrot, and that becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Lesson: Persuade yourself that the foods on your meal plan are filling and indulgent.

At the end of the day, eating sensibly and exercising requires will power. Here, too, science is revealing previously unsuspected aspects of this precious commodity.

Psychologist Roy Baumeister of Florida State University has shown that will power is a finite resource just like, say, energy; if you use a lot of it for one thing you have less left for another. People who are on a strict diet have trouble resisting the siren call of buying, for instance. Having deployed their self-restraint on passing up dessert at lunch with friends, they have none left to resist that amazing pair of shoes calling to them from the shop window.

And, if all else fails, there’s always New Year 2013!

Easy Rules for a Stay-Slim Life

Will power is limited. Arrange your life so you don’t need to tap into it so often.

Shop lite.

Don’t buy calorie-laden, temptation foods in the first place. If you do buy them, put them as far out of sight and reach as possible.

Eat at home.

Scarfing down thousands of calories at a restaurant is just too easy.

Keep a journal.

Make a record of your weight-loss project—and don’t skimp on the self-praise. On a day when you couldn’t resist the ham, cheese, and mayo-stuffed triple-decker, seeing how abstemious you were on days past can be a real confidence builder.

Sleep better.

Because sleep deprivation can sap will power, make seven or eight hours per night of shut-eye a priority.

Reward yourself.

Everyone needs rewards, and frequent little ones can help will power. Try incorporating a treat into your weight-loss regimen. A 2011 study in the Journal of the American Dietetic Association found that dieters who ate one dark chocolate each day lost the same 11 pounds over 18 weeks as those eating the same foods but without the chocolate.

Don’t Overdo it.

Pledging to lose weight is hard enough, and trying to make other lifestyle changes at the same time will weaken your overall resolve. Get real! You can’t have it all. Don’t start a stressful project at work or at home just as you launch your weight-loss plan.

Eat More often!

Another tip that has emerged from a better understanding of physiology and physiology is that eating stimulates the digestive system to store glucose and fat, which increases metabolism and quells appetite. Between meals, fat and glucose are released from storage to keep our cells running, and metabolism slows. Bottom line: Many dieters have better results if they eat five small meals a day rather than three large ones. Eating more often keeps metabolism elevated and prevents the blood-sugar crashes that can make you devour an entire pint of Ben & Jerry’s. In contrast, if you eat fewer than 1,200 calories a day, your body, which thinks famine is at hand, hunkers down in survival mode, slowing down your metabolism and promoting fat storage. And feeling chronically hungry eventually makes all but the most self-flagellating of us abandon the diet.

May I Take Your Order?

Deciding what to order in a restaurant can be overwhelming—especially for someone on a restricted diet, or who is determined to follow through with that once-and-for-all resolution to reach a healthy weight. Add to that challenge the easing of the economic downturn, and you’ll likely find yourself perusing more menus than you did last year. Industry forecasts predict restaurant sales to reach $580 billion this year, a 2.5 percent increase in current dollars over 2009 sales. Fortunately, restaurants are responding to the 75 percent of consumers who say they try to eat healthier while dining out, according to the National Restaurant Association.

Joy Bauer, nutrition and diet expert for the TODAY show on NBC, says the food industry is “really starting to feel the pressure to make changes.” In Bauer’s opinion, the biggest menu myth is that it’s impossible to make healthy choices when eating out. “It’s not where you eat, it’s what you eat,” says the nutritionist. The challenge is overcoming the temptation to order high-fat fare. And expanded menu options are there to help, with color-coded dietary selections or a key bank of symbols used to indicate if an item is gluten-free (GF), vegetarian, heart-healthy, low-fat, or low-carb. Many even include a specific section for special diets, such as the Applebee’s “under 550 calories” choices, or Bob Evans’ “Fit from the Farm” menus. Don’t be shy when it comes to customizing your order in the name of health, either. Restaurants such as Cracker Barrel, for example, offer a “Tasty Alternatives” menu, including Egg Beaters, turkey sausage, sugar-free syrup, Promise Spread, and low-sugar fruit spread.

Seniors can also take advantage of the expanded menus at most casual dining restaurants. Denny’s, for instance, has a special 55-plus menu for breakfast, lunch, and dinner—offering modified portions and special discounts. These conveniences are especially important for diners who may eat out once or twice daily.

While most nutrition experts agree the best way to control your diet is to prepare your own meals, it’s not always a practical option, especially as the summer travel season approaches. If you find yourself feeding your family via drive-thru, take note of Bauer’s healthier suggestions on the menu boards this year:

“Taco Bell started heavily marketing its Fresco line, which features lower-calorie, lower-fat options. Burger King revamped their children’s menu, and KFC launched its grilled chicken line,” says Bauer. But beware: Many chain restaurants still compete for the biggest, most over-the-top burger, warns Bauer. “They’re part of the problem, but by offering healthy, convenient meal options, they can be part of the solution.”

• Order a salad with grilled chicken and low-fat dressing or a basic grilled chicken sandwich (hold the mayo; add mustard, salsa, ketchup, or BBQ sauce instead) with a fruit cup or low-fat yogurt.

• Stick with calorie-free drinks such as water, diet soda, or unsweetened ice tea.

• If you’re bent on ordering a burger or fries, order the smallest size available. (A plain hamburger at Burger King has a modest 260 calories—compared to a BK Steakhouse XT burger, which averages 1,000 calories and more than 60 grams of fat.)

• For pizza, opt for thin crust; veggie toppings are a bonus. (One slice of a large cheese pan-crust pizza from Pizza Hut contains 360 calories; the same slice on thin crust, 260 calories.)

• For subs, order a small turkey sandwich piled high with lettuce, tomatoes, onions, hot peppers, and pickles. (Skipping the cheese at Subway can save 60 calories; hold the mayo to save 110 calories; or choose light mayo, which has 50 calories per tablespoon.)

• And don’t fall for the better “value” items—you may get more food for the money, but you pay the price with your waistline and health.

More healthy selections from some of your favorite restaurants can be found at healthydiningfinder.com.

Breakfast

Cracker Barrel

Oatmeal with Banana Topping

Calories: 280

Fat (g): 4.5

Saturated Fat (g): 1

Protein (g): 6

Carbohydrate (g): 31

Fiber (g): 4

Cholesterol (mg): 0

Sodium (mg): 180

Egg & Cheese Grilled Breakfast Sandwich

Calories: 380

Fat (g): 14

Saturated Fat (g): 6

Protein (g): 18

Carbohydrate (g): 43

Fiber (g): 2

Cholesterol (mg): 190

Sodium (mg): 620

Bob Evans

Veggie Omelet with Fruit and Toast

Calories: 272

Fat (g): 2

Saturated Fat (g): 0

Sodium (mg): 549

Blueberry-Banana Mini Fruit & Yogurt Parfait

Calories: 177

Fat (g): 1

Saturated Fat (g): 0

Sodium (mg): 61

Lunch & Dinner

Bob Evans

Chicken Spinach & Tomato Pasta

Calories: 526

Fat (g): 16

Saturated Fat (g): 4

Sodium (mg): 533

Potato-Crusted Flounder with Potato and Broccoli

Calories: 415

Fat (g): 8

Saturated Fat (g): 3

Sodium (mg): 527

Chili’s

Guiltless Grilled Chicken Sandwich with Veggies

Calories: 610

Fat (g): 12

Saturated Fat (g): 5

Protein (g): 44

Carbohydrate (g): 78

Fiber (g): 8

Sodium (mg): 1310

Cracker Barrel

Spicy Catfish (Grilled)

Calories: 120

Fat (g): 5

Saturated Fat (g): 1.5

Protein (g): 17

Carbohydrate (g): 1

Fiber (g): 0

Cholesterol (mg): 45

Sodium (mg): 300

Damon’s Grill

Mix & Match: Chicken & Steak Sizzling Platter

Calories: 410

Fat (g): 18

Saturated Fat (g): 7

Protein (g): 47

Carbohydrate (g): 13

Fiber (g): 3

Cholesterol (mg): 115

Sodium (mg): 530

Chevy’s Fresh Mex

A La Carte: Salsa Chicken Enchilada

Calories: 240

Fat (g): 12

Saturated Fat (g): 4.5

Protein (g): 15

Carbohydrate (g): 19

Fiber (g): 3

Cholesterol (mg): 45

Sodium (mg): 510

Applebee’s

Grilled Shrimp & Island Rice

Calories: Under 550

Asiago Peppercorn Steak

Calories: Under 550

Grilled Dijon Chicken & Portobellos

Calories: Under 550

Spicy Shrimp Diavolo

Calories: Under 550

Asian Crunch Salad

Calories: Under 550

Grilled Shrimp & Island Rice

Calories: Under 550

Joy Bauer is author of the No. 1 New York Times bestseller Joy Bauer’s Food Cures (2007) and Slim & Scrumptious, released in April 2010.