North Country Girl: Chapter 11 — Summer Sleep-Away Camp

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

The days pass slowly in elementary school, with any occasion that broke up the routine a cause for celebration. The one or two days Miss Ritchie fell ill, we were minded by a clueless substitute or by the principal herself, Miss Brown. We would fess up to what page we were on in our math workbook, read silently for hours, and when all other options were exhausted, Mr. Swan would wheel in the projector and set up a black and white film on the wonders of electricity or atomic energy. We loved them. As much as I adored Miss Ritchie, a day not spent watching her fill up the blackboard with decimals and parts of speech was a good day.

We rarely went on field trips. Once a year we would go to the St. Louis Historical Museum, which was boring beyond belief, and once a year to the Chisholm House. The Chisholm House was a turn-of-the-century mansion chock-a-block with stuff: heavy ornate furniture, oversized paintings of Chisolms with gilt frames that had turned dark with age, chipped mannequins in antique dresses and crooked wigs propped around a tea table. There was one room devoted to mourning attire, which was creepy and fascinating, with displays of elaborate jet necklaces and jewelry made of the dearly beloved’s hair.

Our fourth grade classroom had occasional visitors. In October a woman came to guilt-trip us into ruining our Halloween by asking for money for UNICEF instead of candy. She spoke to us about starving children in Africa and handed out little orange and black “Trick or Treat for UNICEF” houses that we were supposed to fill with pennies and bring back to school on November 1. I am sure that all of us, right down to the most goody-goody — who was probably me — simply pawed through our mothers’ purses to fill those boxes. If I had actually tricked or treated for pennies instead of candy, I probably would have gotten both, but I wasn’t taking any chances of missing out on the once-a-year binge fest of Bazooka and Dubble Bubble; Zagnut, Bun, Bit-O-Honey, Zero, and 100 Grand candy bars, wax lips and moustaches, candy necklaces, and the home-made popcorn balls given out by a lady who lived a few houses down from us on Lakeview Drive. Even the disgusting tooth-cementing Mary Janes were welcome, to be traded later at a discount.

We also had a fireman come to Congdon to lecture us on fire prevention. He left us with a safety check sheet depicting an open-face house with flames from different causes breaking out in every room. To this day I have an irrational fear of oily rags, although I have no idea why anyone would keep oily rags in their home.

***

In the spring, the boys were shunted off somewhere for an hour while we girls stayed in the classroom for a slide presentation on the YWCA summer camp, Camp Wanakiwin. It looked like heaven. A trampoline! Archery! Canoes! Fireside sing-alongs! And best of all, real horses! Our local dairy, Springhill Farms, offered Shetland pony rides to little kids and there was also a farm where I had been taken trail riding once by my dad, who bragged to the owner that he was an excellent rider. As we approached the barn at the end of the ride, even though we had done nothing more exciting than a three-minute jostling trot across a field, my dad’s horse took off for home like Sea Biscuit, ignoring my dad’s curses and frantic rein pulling, which only succeeded in veering the horse to the right. Dad slammed into the side of the barn door and went sailing off the horse. After that, when my sister and I begged to go riding, he would let each of us invite a friend, and then sit in the car smoking and reading the paper for an hour.

There was no instruction on those trail rides, outside of being told that if I held on to the saddle horn and the horse started to gallop, I would break my thumb; we got on the horse, rode through woods and fields, dismounted, and had a Nehi grape soda from the pop machine. Camp Wanakiwin offered riding lessons, as long as you had special permission from your parents and paid an extra $20 fee.

I had managed to lose my Fire Prevention Check Sheet in five minutes, but I clutched the Camp Wanakiwin pamphlet to my chest all the way home, where I showed it to my mom and begged to go to sleep away camp. She couldn’t say yes fast enough, probably amazed that her introverted kid actually wanted to be around other girls for two weeks straight, and delighted at anything that would pry my nose out of a book.

We then called the Lindburgs in Carlton, to see if my old friend Judy, who was even more horse-crazed than I was, wanted to go with me to camp. There was one problem: Judy, at the advanced age of ten, still wet the bed nightly. While the rest of us arrived at camp with sleeping bags, Judy came with a rubber mattress cover and several sets of bed sheets, which she and our cabin counselor whisked off her bunk every morning and brought to the camp laundry. Minnesota nice, none of the other girls in our cabin ever said a word.

Camp Wanakiwin (in Ojibaway, “Place of the Frozen Girls”) was not quite as depicted in the slide show and the brochure. There was a brand new trampoline, where a number of girls broke arms or collarbones or wrists in the two weeks of camp. There was archery, where you needed to have the upper body strength of Superman to draw the bowstring far enough back to reach the target pinned to a haystack a mile away; my arrows simply fell off the bow and on to the ground.

And there was horseback riding, where I was humiliatingly assigned to the Beginners group, despite my vast pony and trail riding experience. This meant I spent twelve out of fourteen days riding around in the ring, as if I were on a carousel, when I had pictured myself galloping through the fields like Dale Evans.

Then there were the features that the slides and brochure didn’t show: There were two bathhouses, one for the younger girls and one for the older, with very stinky toilets and cold water showers. Most of us regarded our daily swimming lesson in the icy waters of Hanging Horn Lake as all the washing up we needed.

A lot of government surplus food made its way into the Camp Wanakiwin kitchen. Every meal included a big pitcher of a disgusting pale blue liquid made from powdered milk. Thankfully there were also pitchers of off brand Tang for breakfast and fake Kool-Aid (always red) to wash down lunch and dinner, but on cereal mornings the only option was to eat dry corn flakes, a situation I remedied by piling on spoonfuls of sugar, something I was not allowed to do at home. There were huge blocks of bright yellow cheese the exact consistency of modeling clay, and boxes of powdered eggs, which made watery scrambled eggs that looked like the last bits of throw-up. I didn’t eat real eggs or cheese, so I never touched the stuff, even though picky eaters were frowned upon by the camp staff. Pancake breakfasts and spaghetti dinners were the highlights; desserts were Jell-O or applesauce or canned peaches or other things that aren’t really desserts. We were allowed to spend a small amount on candy each day at the camp store, which was only open after lunch, followed by the mandatory “Quiet Time,” my favorite camp activity, an hour I spent lounging on my bunk, eating Mike and Ikes and reading a thread-worn and musty old novel from the camp’s very limited library.

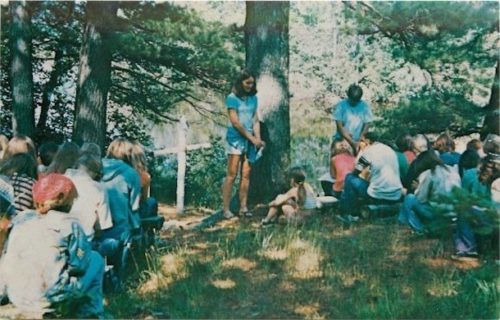

The brochure hadn’t mentioned “Quiet Time;” there was nothing about the required Sunday services either, although that should not have been surprising as the camp was run by the Young Women’s Christian Association. Most of the girls were herded down to a lakeside chapel, where they sat on benches surrounding a white wooden cross listening to counselors read from the Bible. Judy and I were not so fortunate. We Catholic girls were rousted out of bed early Sunday morning to board the camp bus into Moose Lake for eight o’clock Mass (in Latin back them) in a small stuffy church.

Two girls in our bunkhouse, the Applebaum cousins, got a free pass on Sundays. They were exotic Jewish specimens from Minneapolis whose family owned the Applebaum chain of supermarkets. The minute we met, before I had a chance to wonder why rich girls would be at a camp with cold water showers and government cheese, the cousins informed me that because they were Jewish they were not allowed at any of the nice summer camps closer to the Twin Cities. I saw no reason to not believe them, but it seemed an embarrassing thing for someone to admit. The Applebaum cousins were pretty, both with long lustrous hair and olive skin. They were going into sixth grade, so they were almost two years older that I was. They claimed to have boyfriends, and they knew exactly how babies were made. They gleefully shared that information with the rest of the cabin one night after lights out, provoking such a shocked chorus of “Gross!” “Ew!” and “Yuck!” that our counselor had to come out of her room to shush us.

We were expected to be asleep by nine, and usually were, as we were woken every morning at six to be in place for the daily flag raising ritual half an hour later. The rest of the day was one damn activity after the other. On our first day at camp, every girl was given a slip of paper with the schedule of sports and classes she had signed up for, plus the mandatory daily swimming lessons, and some kind of chore, such as setting up for meals. There was tennis, which I was terrible at, badminton, which I sucked at almost as much but which seemed to matter less, volleyball and softball, with the potential of being hit in the face really hard by a ball, and arts and crafts, where I was as good as anyone else at making lanyards and flower pressings. There was also boating, which involved four girls lifting an incredibly heavy wooden rowboat into the lake and then going around in circles for an hour, trying not to whack each other with the oars. You had to pass boating before you could advance to canoeing, which is the only reason anyone signed up for it.

My swimming class was scheduled for eight o’clock, right after breakfast and before the sun had the chance to raise the water a single degree. It was hard to learn any of the strokes when you were blue, teeth-chattering, and had your arms tightly wrapped around yourself in a vain attempt to keep from freezing.

In the evening, we had sing-a-longs, nature lectures, bonfires, the camp talent show, and Christmas in July, where we decorated a fir tree with paper chains, exchanged Secret Santa presents (“I made you a lanyard!” “Aw, I made you a lanyard too!”) and a counselor dressed as Santa Claus gave out packages of government cookies which we washed down with lukewarm, watery government cocoa.

Despite the bad food, the cold showers, the even colder lake, and my inability to become proficient at a single sport, I loved Camp Wanakiwin. I loved being on my own, even if my day was as regimented as a Red Army soldier. Unlike some of the girls in my cabin, including Judy Lindburg, I wasn’t homesick for a minute. Then a week after I arrived, I watched in horror as a big green Chrysler pulled into camp. I knew that car. Out popped my father and my sister Lani, carrying a small suitcase. Despite our constant bickering, she had missed me and thrown tantrum after tantrum at not being allowed to go to camp too. She was only six and you were supposed to be seven to go to Camp Wanakiwin, but my father knew people and pulled strings and managed to get Lani off to camp for the second week of the session. Fortunately, I rarely had to see her, as the activities were divided by age, so twelve and thirteen year olds wouldn’t be bouncing smaller girls off the trampoline or beaning them with softballs.

Seven days later my parents came to collect us. My bunkmates and I exchanged addresses, promised to write, and made plans to reunite next summer at the same session. I spent three more summers at Camp Wanakiwin, and although I never saw the Applebaum cousins again, each summer provided a boatload of sexual misinformation whispered among my sister campers after lights-out.