Chautauqua: Family Get-Aways for Knowledge, Beauty, Community

In 1874 Ulysses S. Grant was serving his second presidential term, federal Reconstruction efforts were attempting to heal the festering wounds of the Civil War, public school education was well underway, modern science was making inroads against Christian fundamentalism, and the Sunday school movement was gaining steam in churches across the land. Two gentlemen, Lewis Miller (whose daughter Mina married Thomas Edison) and John Vincent (a Methodist bishop), hoping to create an enlightened Christianity, launched a movement on the shores of Lake Chautauqua in western New York to train Sunday school teachers in religion, science, art, and music.

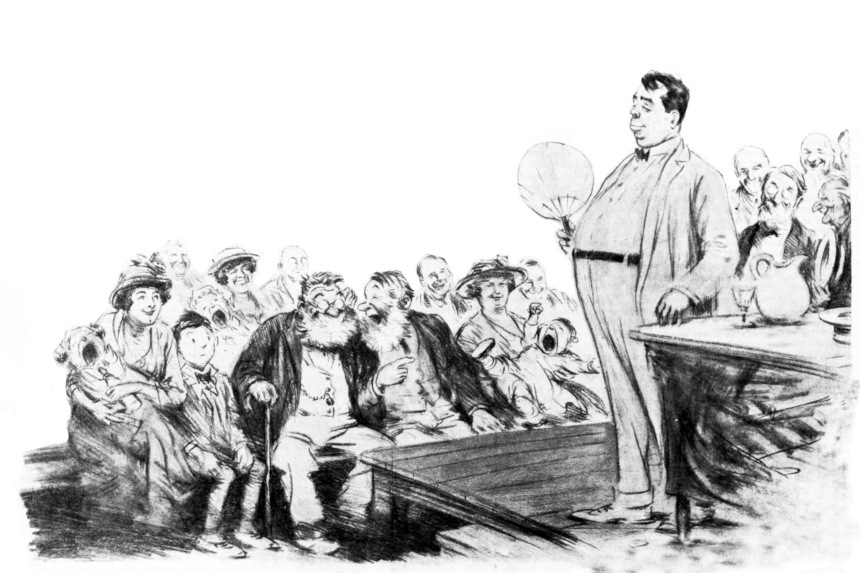

The Chautauqua movement grew rapidly, spreading across the nation, including circuit or tent Chautauquas, one of which visited my hometown of Danville, Indiana, each summer in the late 1800s and early 1900s, attracting twice our town’s population the week it was held. This was half a century before I was born, so I had never heard of the Chautauqua Movement until 2003, when Bay View Chautauqua near Petoskey, Michigan, invited me to speak at their annual sessions, wildly overestimating not only my speaking ability but my drawing power. Nevertheless, it was an enjoyable week, they invited me to return, and I’ve since spoken at half a dozen Chautauquas around the nation, including that charming village on the shores of Lake Chautauqua where it all began some 145 years ago.

At its peak, in the mid-1920s, over 10,000 Chautauqua programs attracted 45 million people when America’s population was 116 million.

Alas, the Sunday school movement that inspired the Chautauqua movement is on life support, driven to its deathbed by declining church attendance, youth sports on Sunday morning, and the near impossibility of finding someone whose idea of a good time is arranging ark animals on a flannelgraph board. Nevertheless, the Chautauqua lives on, despite brushes with death during the Great Depression, World War II, and the 1960s, when cottages that now sell for $600,000 could be had for $5,000. They didn’t start with cottages, but with tents, then cement pads when people grew weary of camping in mud. Winding streets, sidewalks, and cottages soon followed, and now most Chautauquas feel like a Jimmy Stewart movie set from the 1940s — big, broad porches with rocking chairs, flower pots, and porch swings.

Chautauqua’s greatest challenge today is attracting people who aren’t white and well-off, a problem many American institutions face in this age of demographic changes and our heightened awareness of structural racism. The preacher of the week when I lectured was the Reverend Doctor Otis Moss III, the black senior pastor of Chicago’s Trinity United Church of Christ, doubtless one of the finest preachers in America, who could, I do believe, persuade the devil to convert. His sermons were received each morning with standing ovations from Episcopalians, Methodists, agnostics, and Jews.

This road to inclusion has not been smooth. The Bay View Chautauqua in Michigan is still reeling from a recent divide when a significant number of cottage owners supported a 1947 bylaw forbidding non-Christians from owning a cottage, effectively blocking a Jewish woman from inheriting a cottage her Christian family had owned for generations. Fortunately, a sizable majority of residents eventually rejected the bylaw, which seems only fitting, given the religion of their Savior. That same Chautauqua, from 1942 to 1959, forbade people of color from purchasing or renting a cottage. So there is painful history to overcome.

In these days of isolation, partisanship, intolerance, and division, the Chautauquan spirit might well be the cure for what ails us.

Happily, this narrowness of spirit is rare. The vast majority of the Chautauquans I know are thoroughly committed to the ideals of justice, education, and equality. They read, study, engage, and think. They embody the best of America, and only rarely the worst. It was Theodore Roosevelt who said the Chautauqua was “the most American thing in America.” Sadly, our America includes not only moments of greatness, but also moments of meanness, and no institution is exempt.

My moment at the New York Chautauqua was surreal, having never spoken from the same dais as Ulysses S. Grant, Booker T. Washington, Susan B. Anthony, Theodore Roosevelt, Amelia Earhart, and Thurgood Marshall. Franklin Roosevelt had been there too, just down the street in the Amphitheater in 1936, when 12,000 people gathered to hear his famous “I Hate War” speech. My crowd was sizable, but just when I was starting to feel self-important, I was told Chautauquans would turn out in droves to hear a book of recipes read aloud. So there is that.

It’s odd that something so historically significant is so little-known today. At its peak, in the mid-1920s, over 10,000 Chautauqua programs attracted 45 million people when America’s population was 116 million. But we were joiners then, filling our days with memberships in churches, fraternal organizations, women’s clubs, veteran’s organizations, and the like.

Those days are gone, according to Robert Putnam, the author of Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. Yet the Chautauquas persevere, and are in many locations enjoying revival. Auditoriums that sat nearly empty 40 years ago now teem with people. Hundred-year-old cottages have been shored up, renovated, repainted, and are now filled with four generations of families the whole summer long.

I don’t suspect I’ll ever own a Chautauqua cottage, given the limits of my income, but I’ve fully bought in to the aims and goals of the Chautauqua movement, the conviction that our national salvation will be found in knowledge, beauty, collegiality, and community. In these days of isolation, partisanship, intolerance, and division, the Chautauqua spirit might well be the cure for what ails us. In the morning, its participants engage one another on the issues of the day without rancor or wrath, return to their cottages for lunch and a nap, then return in the afternoon to attend a workshop on, among other things, sailing, baseball, the history of Chinese pottery, 3D printing, or medicinal herbs.

In most Chautauquas, cars are discouraged, so kids ride bicycles and adults walk, which is how evenings are spent, unless one prefers porch-sitting. Televisions are permitted, but not encouraged, and the average Chautauquan is loath to admit watching it, in much the same way a Baptist would only reluctantly confess to tipping back a beer. And why would any sane person sit indoors to watch America’s Got Talent or The Voice when they could sit in a lakeside amphitheater on a pleasant summer evening and hear music so lovely it reduces one to tears.

The most compelling evidence of Chautauqua’s lure is that in the two weeks I spent at Chautauquas this summer past, I saw less than half a dozen people on their cellphones. No one was impulsively tweeting their every thought, posting pictures of their meals on Facebook, or trolling political candidates. That alone was worth the price of admission.

Philip Gulley, who writes the Post’s Lighter Side column, was finalist for the Thurber Prize for American Humor for his memoir, I Love You, Miss Huddleston.

This article is featured in the July/August 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Citadel of learning: Chautauqua’s Hall of Philosophy, built in 1874, was an open-air structure modeled after the Parthenon at Athens. It sat under a canopy of trees that shaded and cooled the Hall during the hot summer months. (Chautauqua Institution Archives)