“One of Us Must Die” by Edmund Gilligan

Edmund Gilligan wrote for the The American Magazine, Cosmopolitan, Argosy, and the Post between 1956-1962. His short story “One of Us Must Die” covers the enthralling tale of a crew battling the sleet-chilled Atlantic waters while at sea.

Published on September 8, 1962

By lamp-lighting time alongshore, the Medea of Gloucester lay sound asleep at the herring wharf in Shelburne, Nova Scotia, where the Roseway River empties into the Atlantic. The schooner had hurried across the Bay of Fundy under a whole mainsail because she had never gone fishing so late in the year, and her people wished to find shelter to size things up. There had been signs of bad weather far behind her. Off Cape Sable, her landfall, she had found more reasons to hurry. The westerly wind had become curiously dry, and the barometer had risen. Later she had sighted hurricane rollers rising out of a very long swell. When she swept along the western edge of Roseway Bank, the squally halo around the first quarter moon had vanished, and the barometer had fallen to “Fair.” So she slept in peace, the uneasy peace of November.

Huddled under the eaves of the icehouse, three dark-clad men gazed at the Medea as she lightly rose and fell to bow line and stern line, her iron gear atinkling. By moonlight and starlight the Medea displayed her old-time beauties: bottle green hull, cherry-stained bulwarks, white crosstrees and her name in gold, mildly gleaming under skeins of frost. Those men knew the Medea well enough, and they knew why she lay there: to buy their herring in the morning to make bait for the halibut on far Banquereau, which was her workshop. Herring they had in plenty on ice, and the sale meant much to them, coming so late in the season. They would have a little more Christmas money. They understood that the Medea had dared to make a November voyage for the same purpose. There had not been much money earned that fall on the Grand Banks; the price of halibut had been too low at Boston. Now it had risen.

Talking of these matters, they crossed the wharf, took a kindly look at her mooring lines and walked up the lane, praising the fatness of their herring and declaring the Medea’s skipper surely would be pleased when he ran his testing thumb down the herring bellies and found them fresh.

In the galley of the Medea, aft of her forecastle where eighteen of her dorymen slept in their tiered bunks, one man stayed merrily awake. He was her cook, known to the Grand Bankers as “Long Tom” because his handsome head, well silvered now, lay so far from his feet. The dorymen asserted that in any kind of fog he couldn’t see his boots. He answered that his boots weren’t worth such a difficult glance anyway.

Tom had finished his ordinary chores. Mugs and dishes were washed and put away, his pans scoured. He had just taken twenty loaves of bread out of his great oven. In there now his apple pies were already adding a cinnamon bouquet to the other delicious fragrances. He had yet to brush the top crusts with a gull’s feather dipped in butter. The feather and butter were at hand.

At the moment, Long Tom was resisting temptation of the worst kind — one offered by himself. He was a cook who enjoyed his own cooking. In fifty years of labor in that one galley he had never tasted a dish which he could not praise. And he tasted all that he made. Even when he hard-boiled fifty eggs for the shack locker, where dorymen coming off watch could “mug up” on tea and cookies, he always ate one or two to make sure. His chocolate cake had made the Medea the envy of the Gloucester fleet. Such cakes bore fudge icing, and Long Tom couldn’t tolerate an icing less than half an inch thick.

His present temptation had a chocolate nature too: precisely, a yard-square tray of fudge cooling on a shelf under the half-open port. He had used the last of his Jersey cream for it, and he had put into it an array of excellent English walnuts. He had a benevolent purpose in mind, and he intended to carry it out when the fudge had hardened enough to be cut. He had to combat his desire to taste. To that resistance he carried all the force of his plumpness and of his agile mind.

At such a crisis Long Tom took refuge in the Bible, not exactly for instruction but chiefly to employ his mind. The Book of Job had served him well a thousand times. Long Tom had never quite settled the question of Job. “Patience of Job, do I hear you say? Why, he don’t strike me as being a model of patience. What answer did he make to his chum? ‘Wherefore do the wicked live, become old, yea, are mighty in power?’ And didn’t he come out all right in the end? Aye, there’s something of a sea lawyer about that man. Shouldn’t be surprised if he’d once been before the mast — and a poor cook in the galley.”

When he had beguiled his heart by thoughts of Job and Satan, he turned in a soberer mood to The New Testament, in which he always read much during the Christmas season. “Matthew, Mark, Luke or John?” He chose John, and for a time he sat enthralled, because these were saints whose hearts spoke well to his. He placed the Bible in its tin box and turned to the cutting of the fudge. He had all but finished when Satan whispered, “My dear Job — I mean, of course, my dear Tom — isn’t that a rather odd-looking piece over there south by east, a little east? I mean that one with a whole kernel in it.”

After he had eaten it and savored each crumb to the last, Tom looked behind him quickly and seemed surprised. “Well, now, I really didn’t have to do that. I knew it was good, very good.”

He filled three plates with fudge and climbed the companionway step by step, carefully. On the way aft he paused in the lee of the starboard nest of dories and measured the starry night. The Pole Star burned fierce as a bonfire, and he could make out even the faint stars of the Little Bear, so clearly they shone in the winter hovering aloft. He passed to the cabin and went below into its dusk. He put the plates down and rapped his knuckles against the great lamp, burning low in its gimbals. It was his duty to keep lamps trimmed and full.

In the starboard bunk Captain Matthew Duane lay asleep, his boots near at hand, ready, even in harbor, to be jumped into. Under the black curve of his moustache his lips shaped a stern word. He frowned and gently struck his mouth, just as if it had spoken of its own accord and had vexed him mightily in his dreams. “I’d give a lot to know what he said,” whispered Tom. He gave a plate of fudge. The skipper whispered again and began to turn over, his secret kept.

Long Tom stepped lightly to the port bunks. In the lower one lay Dick Rodney, the oldest hand in the Medea and the best sailing master ever she had. She liked him, that vessel did, and willingly performed things for him that she would not for others, especially when close-hauled and beating to windward to hit the lively Wednesday market at Boston. Neither chick nor child did that man have, as they used to say of bachelors in the bygone days. On the Medea’s tenth birthday he had come aboard, a greenhorn, and he had never left her even to lay off one trip. The sea and the oars and the hauling of halibut had shaped him into the Atlantic style: heavy-shouldered, lithe in the long legs and able, very able, in the many uses of the great frost-scarred hands calmly folded together in the grace of dreamless sleep. Dark hands they were, half again as large as the cook’s, and his were not a boy’s hands by any means.

“Happy birthday, Dick,” whispered Long Tom, although it wasn’t anybody’s birthday and he was just trying to entertain himself. “Happy birthday — and may you have another one very, very soon.” He placed Dick’s portion at the foot of his bunk, where his pipes lay in a rack of white porcelain, an ancient thing with odd English words on it that had been fished up one day on Sable Island Bank.

In the upper bunk a man lay awake. Long Tom had no difficulty in standing face-to-face with him; he was tall enough for that. Such wakefulness surprised Tom not at all. He had expected it; in fact, this doryman — greenhorn, rather — was the reason for his night visit. He knew well enough what must be the thoughts of a youngster on his first trip to stormy Banquereau — and in November. He had known the lad’s father, Dennis Nolan, a good man in a vessel and, in a dory, the best of dorymates. Now he saw in the gazing eyes and the thick wheaten-colored shock of hair the father’s eyes and the father’s head. The young man’s forehead shone white in the dim lamplight because he had been living ashore. On the voyage across Fundy, Long Tom had watched the new hand with affectionate care and had helped Dick Rodney in the schooling of him, for Dick took charge of the greenhorns one by one through the Grand Banks seasons. This one now required something more than lessons in seamanship.

“You don’t sleep, young man?”

“No, sir, I don’t. I’ve been thinking — and it keeps me awake.”

“You’ve Dick Rodney for a dorymate, and he’s taught you well coming over, so you’ve no cause for worry, David.”

“You both been good to me, cook.”

“And I brought something for you right now.” He held out the plate. “Just you take some of this, David, for I know you’ve a sweet tooth, and a sweet tooth satisfied — ah! that puts a man asleep. So I guess you’ll be all right, young man, if now you take another piece and fall asleep and sort of work up an appetite for breakfast by the right kind of dreaming. Aye, the young need sleep. And so good night.”

In the afternoon, after her bait had been stowed in ice, the Medea took the tide that served her. Under headsails only, she passed through the harbor entrance and, once outside, laid on all her muslin and was soon running free to the chosen fishing grounds.

Now, standing among the other dorymen on her streaming deck, young Nolan learned to cut bait in the larger chunks required when a vessel is rigged for halibut. Dick Rodney stood by him and showed him how to thrust the chunks onto the big Norway hooks, hanging a fathom apart on shorter lines tied to the main line of the trawl. He taught him the skill of coiling the baited hooks on squares of canvas to be lashed into bundles called “skates.”

“And once a halibut has taken hold,” said Dick, “he ain’t hard to haul — not in winter, I mean — because we’ll be fishing in eighty fathoms maybe, and he’s dead beat by the time he tugs all that way. Now in summer, when you take fish in forty fathoms, they have a short fight coming up and come to the gaff strong and frolicsome. You understand me, my boy?”

“Yes, Mr. Rodney.”

“Ah, you must drop the ‘Mister’ now, David, though it’s real respectful like of you and all right in the beginning and shows your good breeding, but now you must learn to call me ‘Dick’ because we’re dorymates now and forever friends, the best of friends, depending entirely one upon the other in the dory. Besides, you may be calling out a warning sudden like, and ‘Dick’ is the quick word.”

“I’ll do so, Dick.”

Before sunset the westerly wind became very cold and a fine rain fell, almost a mist. Everything cleared up for a time, and the sunset took on a violet coloring. Before the sun really got down, a cloud bank under it changed to a purple hue. Squalls burst out of that bank and ripped along the horizon, making quite a rumpus over the tide rips. Despite the unsteady nature of the weather, the Medea plunged into the dark night and, without taking a reef or changing course, crossed the Sambro Banks and swung away until she changed course to go along the southern edge of Sable Island Bank.

During this sailing toward the Gully of Banquereau, where the gear must be put to work, Dick drilled his greenhorn hard until he knew the use and place for each tool of their trade: bailer and water jar, bucket and food tin, the gaff to hook fish and the gobstick to club big ones. He showed him the bottom plug of their dory, which is knocked out when the dory is hoisted aboard. “In this way, lad,” he said, holding up the plug in his right hand, “brine and blood can be hosed out through the plughole and — watch now! — in this way the plug is jammed into place before we lower again.”

“Dory away!”

Obedient to this order shouted by Captain Duane near the helm, Dick Rodney’s dory, No. I of the starboard nest, came swinging out, and the dorymates went down in it for the opening of a brisk campaign.

Young Nolan sat to the oars and took the direction of the set from the captain’s extended arm: southward. Dick sent down the first anchor to hold the trawl, and after it he flung the buoy carrying the dory’s flag. He took up his heaving stick, a willow wand cut in the marshes of home, and began the deft lifting and tossing of the baited hooks, coil after coil. The baits sank, score by score, down to the halibut roving along the hills and valleys of the ocean floor. With the first skate down, Dick tied on another string, and young Nolan rowed on, eagerly watching the clever hands, the great arms and shoulders bending, swaying at their tasks.

Meanwhile, the Medea, under jib and jumbo, glided northward, dropping the other dories. She came jogging back again, and at eight o’clock, when the sun was well up, she gave the fishing signal : two whirls of her horn crank.

“And now I’ll haul, lad.”

Wearing the white cotton gloves of his trade, Dick laid the trawl line over the wheel of a gurdy set near the bow, and he bent down to haul. The first few hooks came up untouched; the next one brought from him a cry of dismay.

“Dogfish! Drat ‘em!” He slatted the twisting fish against the gunwale and knocked it off. Over the quiet sea came the same slatting noise repeated in other dories, a dismal sound for all hands because it showed that the useless dogfish were swarming below. The shouts of anger soon ceased. The dogfish had fled before the voracious halibut.

“Greenhorn luck, lad! Here he comes!” Its eyeless side uppermost, a halibut five feet long slanted violently to the surface, its snout tugging hard against Dick’s strength. It thrashed in such force that a torrent of foam quite concealed its mottled, rust-hued length. For an instant it floated in an idling way and then turned over ponderously until the two eyes on its right side stared upward dully. Driven by a quick frenzy, it tried to dive. The tight line checked the halibut’s thrust, and at that moment Dick swung the gaff down into the space between the eyes. He hauled on the gaff with both hands until the fish came over the gunwale. Dick struck three times with his gobstick before the fish ceased to struggle.

For the next three days Dick and young Nolan labored from daybreak until moonrise over their trawls, and often they pitchforked their fish aboard the Medea by the light of oil torches on her deck. On the fourth day Dick let his dorymate make his first haul, and up the fish came, hook after hook. Each conquest excited young Nolan until he laughed aloud and struck the gaff so fiercely that Dick had to caution him to take it easy because the dory had almost a full load.

“Hey!” Young Nolan shouted in amazement at the repeated surge far below of a fish that drew the gunwale down. An immense halibut had taken the last bait, and the gashing steel drove it rampaging down and away, back and forth. “Ah, Dick, he’s thundering big!”

Foot by foot, fathom by fathom, the fish yielded to the unfaltering strain on the line. Despite the freezing wind, and the sleet-chilled water, young Nolan sweated over the gurdy. His breath blew vapor out and he gasped harshly. He bent far down to renew his hold on the line and heaved so strongly that the fish came swerving to the foam. Maddened by the hook, it flung its bulk grandly against the dory. In falling, the halibut struck a blow with its tail that actually drove the dory off in a sideways glide.

“Now then, David!”

At Dick’s signal young Nolan swung the gaff high and swung it down and into the massive head. This first blow stunned the fish. It lay sluggish, and thus young Nolan got his chance to club it three times with the gobstick. The fish shuddered its fathom length. Its tail sagged and its gills spurted water with an odd choking sound. The fish rolled on the surface, and they saw that it was by far the greatest yet taken by the Medea. No one man could haul such a fish over the gunwale. Dick lifted his own gaff, drove its blade into the thickest part of the tail, and hauled.

At that very instant, from far off, where the Medea sailed among the other dories, there came the wail of her horn, three times howling the danger signal: Cut! Cut all gear!

One upward glance revealed to Dick the onrush of a squall in which streams of sleet glittered. A November northwester had caught up with them at last. Out of blue water there had risen a black, whitecapped sea. A second comber bulged in its wide path. Both seas joined and doubled in a wave that exploded against the dory. Even such an assault could not overwhelm a Gloucester dory. Its high sides and solid gunwales had been designed, through the Grand Banks centuries, to withstand such shocks and to yield sturdily before them. So their dory slid off smoothly. Half-hidden in the welter of that sea, Dick shouted the Medea’s signal: “Cut! In the name of God! Cut your gear, David!”

Young Nolan had already obeyed the Medea. In a sweep of his bait knife he sliced the line that held the halibut. At this sudden end to the strain, the halibut’s head sank down with such force that the gaff sprang free and rose in David’s hand lightly into the darkening air. Carried high above the gunwale by the sea, the halibut strove hard for a diving thrust of its tail. This furious action had the effect of raising its head once more. In this position it thrashed its tail and head in a vaulting action out of the water and into the air. It fell, and its great mass struck full along the gunwale. The dory turned over.

In the moment before the gunwale sank, young Nolan had tottered in his place, both hands upraised, the bloodied gaff against his yellow storm hat. In the same tick of time Dick had flung himself backward across the mound of fish in an effort to trim the dory and counterbalance the force of the falling halibut. He failed. The other gunwale came up violently. They were pitched outward into the sea.

The sea rolled over them. A second comber followed. Very soon nothing could be seen except the flat bottom of the dory. A ripple of foam spread down the bottom and split against the bottom plug, a battered cylinder of wood two inches high, three broad.

The halibut came up and swam awkwardly this way and that. It plowed through foam and flotsam — bailer, oars, mast — and reddening water ran out of its jaws. The fish sounded. A buoy swam up, struck an oar and swept away on the tide. A white-gloved hand reached out of the water, grasped at the buoy, failed and began a clumsy openhanded thrashing. Dick Rodney came up — first his hand, then his storm hat and at last his gasping mouth, spurting water. Burdened by thick winter clothes and by his boots full of water, he could make no headway.

The dory swung toward him. He flailed the water frantically with his arms. His hands clawed at the bottom of the dory and slipped off. The dory sank with a falling sea. He lunged once more and reached up for the bottom plug, the only thing on which a man could lay hold. In the crook of two fingers of his right hand, he drew himself out of the water. He lay moaning on the flat bottom, his face turned to the unlighted clouds.

Soon the strain of clinging to the plug weakened his grasp. His hand was too big for it. There wasn’t enough wood for his hand to ply its strength. He seized the plug with his left hand. He spewed water, and sucked in air rapidly. As if the neardeath had dulled his heart and senses, he lay sprawled, one boot dragging in the sea. “Ah, thank God, thank God!”

At once, his gravest duty brought him up to his knees. He looked wildly around, then carefully. He saw nothing. A thick gray vapor rolling in from the west drew over the water where the Medea struggled to find her dories. Dick shouted, “David! David!”

Not waiting for an answer, he made one up for himself — that his dorymate had not risen and must be drowning under the dory, where the trawl had caught him. Dick slid off the bottom. Holding to the gunwale, he let himself go down until he could reach into the dory. He came up to breathe. At the third trial his hand found a living thing. He laid hold and drew it toward him. A hand in there seized his arm. Dick bore backward and came up with young Nolan in his grasp. Dick tried to seize the plug, and, as before, a subsiding sea brought it near. He drew himself onto the bottom. He dragged young Nolan to his side and held him close while the water seeped out between the young man’s clenched teeth.

“Breathe, lad, breathe! Safe and sound!” His hand clamped on the plug, Dick made a desperate venture into the lamed consciousness of that young body. He struck young Nolan’s mouth a shrewd blow and rolled him over. The seeping of water became a rough belching. The fog closed over them, a sign that the gale was swinging away to the northward.

David spoke. “It was the fish, Mr. Rodney. Not me.”

“Aye, the fish!” The dory tipped. Under the force of the washing sea, young Nolan slid down and almost into the water. Dick shifted his weight to trim the bottom. When it lay level, he drew young Nolan back. The dory began to slant the other way, and again young Nolan slid down. Dick tried to sink his fingernails into the boards. This he couldn’t do. Another sea struck over them. They lay a time underwater. A cross sea sluiced under the stern. This rising forced young Nolan toward the bow.

“Hold to my arm, lad.”

The other obeyed. In a moment of ease, while the dory rode nearly level, Dick changed his grasp on the plug from his right hand to the left. The strain had become intolerable under the weight and thrust of two bodies depending on his two fingers. Seeing this, young Nolan stared at the narrow hold of Dick’s hand on the wood. “Even you, Dick — you can’t do it.”

“Change your grip to my knee, David. Hold hard now.”

The flooding tide began to turn the dory round and round. Soon the whirling action became so strong that they sagged in a heavier way, and Dick’s grasp on the plug began to weaken rapidly. His fingers slipped from the sodden wood, and they were sliding into the sea when the dory floated level again. Dick renewed his hold.

He could not long maintain it. Had the plug been the size of an oar handle, nothing save death itself could have broken his grasp. His two fingers might keep him safe until the Medea came in her search. Two fingers could not hold two such men. They could save only one.

The wounded halibut came alongside and died. The dorymen began their prayers, muttering together in the overwhelming salt, in the dark of night. Young Nolan cried out, “God have mercy on my soul!” And, “Ah, my poor mother!” Thereupon, he let go his grasp on Dick’s knee and let himself fall down the tipping dory. He had made his choice.

That choice was not acceptable to Dick Rodney. He caught young Nolan at the edge and took his hand and forced the slender fingers into place around the plug. Three of the fingers took good hold.

“Hear me, David? Do you hear me? I’ll swim to yonder buoy and save myself. Hold on desperate and she’ll come to you. And to me.” Saying this, he rose to his knees. He bowed his head in brief prayer. He bent down to young Nolan and said, “The Lord be with you, David. I’ll be on my way now.” He plunged into the sea, and the sea received him.

Long after nightfall the oil torches on the Medea’s deck flared yellow in the west, where she sailed in the traditional circle of search, closing in spoke by spoke to the position that No. 1 dory had taken. The schooner had a hard time finding the other dories in that fog. Now she swept round and round until she picked up the first buoy of No. 1’s trawl, then the second. Very soon a man aloft made out the dory, where it had drifted — well away from its trawl buoys — and they took young Nolan off it.

The first thing they had to tell him was that there had been no buoy near to keep Dick Rodney up. They told him that even the strongest swimmer could not have lived in that sea, and more — that Dick could not swim a stroke. Nor could any man in that vessel. Dorymen refused to learn because nothing could help a heavy clad man in the waters they worked in.

These matters were gently explained to him while he lay in the captain’s bunk, where he could be better tended by the captain and Long Tom. Those two understood quickly enough that their greenhorn had been badly hurt, not in the body but elsewhere — the place of grief. He made no answer to their patience. Nor did he change the stare of his eyes or the firm set of his mouth. He could not sleep — or would not. He neither ate nor drank.

All the first night, after the Medea had swung away on the wearisome beat to windward and to home, young Nolan lay there, his eyes apparently set on the lamp swaying to the schooner’s sway. Long Tom saw that this was not a true gaze, because, when he stood between the lamp and the bunk, the eyes kept on gazing. Thus young Nolan became a mystery to their hearts, one that they had found obscure in their Atlantic myths and legends. They believed he did not wish to live. His face became a white mask when the wind burn faded, and his eyes grew larger in the gauntness changing his cheek. He frightened them. Only his voice — a word — could guide them to his inwardness. He did not say it.

At midnight a change came in the wind; it hauled around until it blew fair for the Medea and once more sent her running free toward her landfall far away. She sailed quietly now; the wind flowing off her sails made the only music. This agreeable change relieved Captain Duane’s anxiety for the other men, who had been handling sail so often. So he sat in the galley with Long Tom and talked in whispers of a sentence by a doryman at dinner: “Too bad. He had the makings of a good doryman.” After saying that, the doryman had taken the watch in the cabin while the captain and Long Tom were at dinner, and he had since gone aft again to watch David’s face. Captain Duane whispered, “They have given the youngster up? Is that it, Tom?”

Long Tom’s answer was cut off by the hasty return of the doryman. “Captain, the poor lad has spoken.”

“What words, eh? Tell us that, Jock.”

“‘Why?’ And that’s all. Just ‘Why?’ “

The captain stepped forward in an eager movement. “And I am just the man that can answer that word!”

Long Tom held Captain Duane back a time while he made a pot of fresh tea and cut a thick slice of bread. He buttered the bread and then poured honey over it. They went aft and stood by the bunk where young Nolan lay — unchanged, impassive.

The captain said, “You hear me, David? Do you at last ask why? And will I not give you the answer? Not mine, but another’s. Were you not sworn friends with Dick Rodney? Dorymates that must cleave to each other even to death? Then —”

Young Nolan had not seemed to be hearing or seeing. Yet, at the last question, his immobility broke. His right hand rose in a plea for silence. His eyes became expressive, and his expression one of bewilderment. He whispered a word. They could not hear it. They bent forward anxiously.

“Eh?” whispered the captain. “What’s that, David?”

They heard: “I did so cleave. I made the offer first, captain, I was ready.” He gave up and passed into a profound reflection, as if he understood for the first time the true meaning of the moment when he had taken his hand away from Dick Rodney’s knee.

At the revelation of this secret, the captain’s eyes turned to Long Tom’s. They looked deeply at each other, not in the earlier questioning way, but in the way of wonder. And this soon changed to a kind of sober joy.

The captain said, “Even so, even so.” In renewed eagerness he sought the words he wished to recite. “Then all the better is the answer, David, and I give it word for word: ‘Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.’ Ah! Were you not at that moment a friend, indeed? Was not his deed friendly?”

His voice loud in the certain power of words that had triumphed down the ages, he laid down the sacred law. In his belief that there could be no task now except the restoration of David’s physical being, his right hand changed from its gesture of entreaty to a sign toward the bread. Nevertheless the sublime words failed, and his own words counted for little.

“Why?” Young Nolan raised his voice to clearness in his tenacious pursuit of an answer. “Oh, he never laid eyes on me before this trip! Oh, my God, why?”

At this, the cry of Job, Long Tom stepped forward and, laying his hand on young Nolan’s forehead, said, “I will answer you, David, and it is my own answer. But first drink this and eat this bread.” He lifted the young man’s head and waited until the mug was empty and the bread gone. He then said, “Listen. This is the holy time of year for the giving of gifts, one friend to another. Didn’t you tell me you was going to give Dick a pipe with a meerschaum bowl for his Christmas? Once we’d sold our fish and had our settlement day and our pay? Aye, you did! Now I hear you offered him another gift — your life. And, Dick, he has given you that very gift. ‘Twas all he had to give — his life. Do you now refuse it, David? No! Take his gift and treasure it all your days. This is Long Tom’s word.”

Young Nolan’s eyes closed. He fell back sighing, and his lips loosened in a return of tenderness. He said, “By the Lord Christ — yes! I will treasure his gift. Forever and one day more.” And he fell into the saving sleep.

Featured image: Illustration by Carroll Jones (©SEPS)

Cold Comfort: My Night in an Ice Hotel

We’ve just left a fine room at the Fairmont Le Château Frontenac, a grand hotel in Québec’s quartier historique, and we are driving on a dark country road. It is 20 degrees below zero Celsius (–4 degrees Fahrenheit). We are on our way to the Hôtel de Glace, the Ice Hotel, full of excitement and dread.

“It’s not that bad in the rooms; just minus five,” a waiter told us a little earlier as we had our last meal before departing. Then he added, reassuringly, “You don’t really feel it. It’s a very dry cold.”

The taxi driver, a francophone Québécois, doesn’t speak much English. “I hope you have a freezing night!” he says after I pay our fare. I think he means it in good spirit, that this is what you’re supposed to say when people are going off to sleep in a modern igloo, the way theater people say “break a leg.”

The path to the hotel has patches of black ice. A million stars look frozen in space, and it is so wondrous it could take your frosted breath away. But your breath comes out in white puffs, like cartoonist’s thought bubbles that say, “… boy, it’s so cold I can’t even think of something funny to say.” At this moment the cosmos seems considerably less miraculous than central heating.

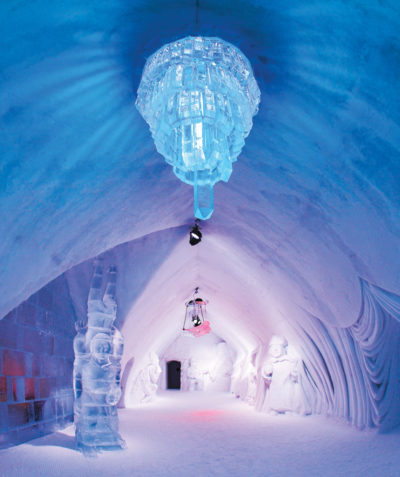

Every kid, I suspect, at some stage wishes to sleep in an igloo. The Hôtel de Glace is a whole complex of them, interconnected halls and chambers cut and carved from 30,000 tons of snow and 500 tons of ice. There’s a chapel with an altar and pews, a bar, and a room with an indoor ice slide. Another space is a gallery of whimsical ice sculptures: an old-fashioned landline telephone, an enormous volume like a Gutenberg Bible, and a vintage deep-sea diving helmet. There are whole dogs and a giraffe’s head and neck sticking out of the floor. A 600-pound ice chandelier with long ice pipes hangs from the ceiling.

The 45 guest rooms come in a variety of shapes and dimensions. Ours, the Snowflake Room, has walls carved with patterns that suggest magnified snow crystals. Queen-size mattresses are on two platforms made of ice. A pedestal and two chairs on either side of a table are fashioned, of course, out of ice.

The Hôtel de Glace would melt on its own, but due to concerns of insurers, they bulldoze it each spring. It takes 15 artists and 35 workers six weeks to create it anew every winter, and it’s open from early January until late March.

The complex has colored lighting that keeps refracting through the ice and settling on the snow like Technicolor dust. The other visitors, mostly Canadians, are a merry crew. Québécois are big on EDM (electronic dance music), even when they’re wearing snow pants and parkas. I admire them for it. When I put on clothes like that I’m even stiffer than usual. They dance on the glazed surfaces of the ice bar and pose for photos with frozen smiles around a flaming chiminea. The hotel brings out blocks of ice and little picks for a sculpting contest. People chip away, making little snowmen or ice hearts.

We go to the spa, which has hot tubs and saunas, and change into bathing suits and robes in a conventional building located behind the ice complex, where there are also toilets, showers, and lockers. The hot tub’s submerged lighting catches the steam hovering just above the water’s surface. We take off our robes and plunge like soldiers into the safety of a trench.

This is all a game of catch with the cold: First it has you, and then you escape by slipping into the hot water, and you lie back looking at the stars and enjoying the hot water and the jets from the Jacuzzi. Strangers want to know where you came from. You’re like brothers in arms facing the same adversaries. Cold hands, warm hearts.

Then it’s time to get out, because you know you can’t stay there all night. There’s no escape. The cold has you from the bottoms of your feet as they touch the icy floor to the top of your wet head. It licks your raised, weeping flesh.

And you give it its taste on your way to dry off and change clothes and get ready for the main event: sleeping. We return to our Snowflake Room and twist ourselves into the sleeping bag liners and stretch our limbs into the mummy bags. I am glad for the advice we received on arrival. For example: put on fresh socks. If you wear the ones you sweated in already, the cold air will circulate and your feet will get colder all night.

The liner works beautifully. There is, I’m sure, some science to this, something about airflows and trapping heat between layers. But what you need to know is that what starts out warm and dry stays warm and dry, and that when the warmth surrounds you, it feels a lot like complete love, the kind of all-enveloping peace you last experienced in the womb.

There is, though, a kind of low-intensity anxiety. Fear, for one thing, that the warmth won’t keep and you’ll wake up freezing. And fear, for another, of not sleeping, of an eternal dark night shivering and shaking like a detox patient. But cold exhausts the body and fear exhausts the brain, and soon enough your wife taps you to complain: You’re snoring.

An arm falls out, and the cold air coats it. Breathe through the nose and the air freezes your nasal passages, and you wake up with apnea; breathe through the mouth, you get a dry throat. I fall back to sleep. The ski hat I brought along comes off, and some arctic spirit massages my head and breathes on the rims of my ears. I twist in my mummy bag to reposition. The bag is rated for 28 below. Eventually it gets to -26. That’s the temperature outside, of course. Inside I have no idea. I suspect it’s getting colder all night, but it’s possible I’m just weakening, waves of cold battering the ramparts of my being.

I’ve slept outside, exposed to the elements in deserts and jungles, and I’ve been in a few really grim hotels, too, but now it comes as a revelation that I am, in reality, a soft man.

I dream of the hours of the night. I dream that it’s morning. Even so, unlike a few guests who bail each night, the one thing I wouldn’t dream of doing is running for

heated shelter. I’d rather be mummified by frost, a stiff on my bed of ice, than to have quit. I have my pride.

In the morning, light pours in through the hole in the ceiling that’s there for ventilation. Light is not just illumination. It brings news: I have survived. This is a modest achievement. I think of the great polar explorers, Amundsen, Scott, Shackleton. They had to melt their sleeping bags before climbing into them. The biggest advantage a modern adventurer has today, a modern adventurer once told me, is not GPS or satellite phones but technical fabrics and advances in footwear.

I lie there a while, enjoying the soft light and serenity, and also girding myself to the idea of unzipping the bag and climbing out. In the end, it isn’t courage that makes me move but a full bladder.

I get up quickly, jiggling a foot into a shoe, careful not to land an unshod hoof on the snowy floor, and give my stiff spine a fillip. Then I stand in a series of shivers and spasms, like a foal getting itself upright, and, pulling a jersey over my swollen dome, I shuffle forward and lurch toward the finish line: a hot breakfast, indoors.

Todd Pitock’s last piece for the Post was “The Healing Power of Baseball in Japan” (March/April 2018), which won an award from the American Society of Journalists and Authors.

This article appears in the November/December 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.