Sean Connery Never Forgot His Humble Beginnings

“I suppose more than anything else,” Sean Connery said in 1964, “I’d like to be an old man with a good face.” No one could deny that his wish came true, particularly after he became the oldest recipient of People’s Sexiest Man Alive honor in 1989 at 59 years old.

Connery passed away in his sleep over the weekend at 90 years old, leaving behind a legacy of popular film roles like his principal portrayal of James Bond.

Though he was widely regarded to have the charm of Cary Grant and the toughness of Marlon Brando, Connery’s foray into show business was a sort of happy accident. He was born into a poor Scottish family and spent his early working years as a truck driver, a cement mixer, and even a coffin polisher. When he landed a role in a touring South Pacific company in London in 1953, he found a passion for performance.

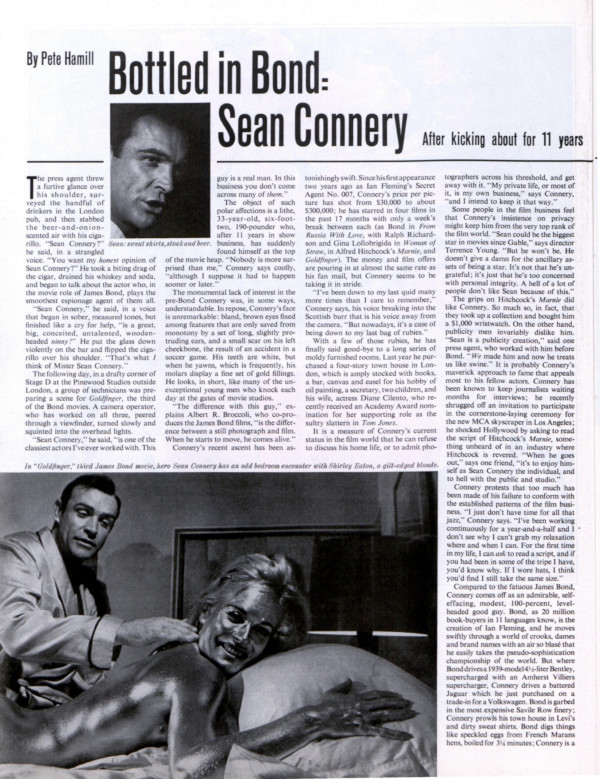

Connery’s debut as Agent 007 in 1962’s Dr. No launched the lucrative spy movie franchise that continues to this day. He became an overnight star, known for bringing tall, dark, handsome life to Ian Fleming’s British agent. Pete Hamill profiled the newly-famous Connery in this magazine in 1964, making much of the Scotsman’s ability to throw his weight around Hollywood. Connery declined interviews, carefully negotiated his contracts, and even demanded to read a Hitchcock script (Marnie) before agreeing to take part. “Compared to the fatuous James Bond, Connery comes off as an admirable, self-effacing, modest, 100-percent, levelheaded good guy,” Hamill wrote.

After Bond, Connery’s career in action and adventure movies chugged along, with roles in Murder on the Orient Express, A Bridge Too Far, and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. He won an Oscar in 1988 for playing Jim Malone in Brian De Palma’s The Untouchables. Though his career seemed to be predicated on sex appeal, Connery found lasting success through his willingness to play along as a character actor.

In 2000, Connery was finally knighted by Queen Elizabeth II after being denied the honor for several years, possibly because of his support for Scottish independence.

Even the most diehard Bond fans might have missed Connery’s right-arm tattoos, barely noticeable in his shirtless scenes. He received them during his service in the Royal Navy, and they signified a firm commitment to his humble roots: “Scotland Forever” and “Mum and Dad.”

Featured image: pv brothers / Shutterstock

Walter Winchell: He Snooped to Conquer

If he is remembered, the journalist and radio man Walter Winchell evokes a few different types of memories. Baby boomers might recall the narrator of the 1959 series The Untouchables. Their children might have caught the HBO biopic Winchell that starred Stanley Tucci as the fedora-donning gossip columnist. Younger people likely won’t recognize the name Walter Winchell at all. But consider this: every time you guiltily click on a link promising a juicy scoop on a washed-up actor, Winchell is somewhere, smiling.

In his heyday, Winchell commanded a collective audience of about 50 million Americans — two-thirds of the adult population in the 1930s. As biographer Neal Gabler claims in American Heritage magazine, anyone walking the streets on a warm Sunday evening in any city in America at the time would hear Winchell’s staccato voice through successive open windows on their way, giving updates on the war in Europe or a famous couple who might be “infanticipating.”

Making and breaking celebrities and politicians in his syndicated columns and radio broadcasts, Winchell built a complicated legacy. Though he often leveraged his platform to give a voice to everyday Americans, Winchell’s lifelong quest for popularity became his own undoing.

A new PBS American Masters documentary, Walter Winchell: The Power of Gossip, offers viewers a new look at how, for better or for worse, Winchell created “infotainment.” The documentary tracks the gadfly’s rise during the Great Depression and his slow decline in the McCarthy era, with Whoopi Goldberg as narrator and Stanley Tucci reprising his role as Winchell.

Director Ben Loeterman says that he was drawn to Winchell’s story as a sort of explanation of the current state of news media: “I think understanding the origins of how news is shaped and delivered and the importance of story, that has become absolutely part of journalism today, started in that sense, I think, with Walter Winchell.”

Winchell’s career arc can be simply understood with his own words: “From my childhood, I knew what I didn’t want: I didn’t want to be cold, I didn’t want to be hungry, homeless, or anonymous.”

In his early years reporting Broadway gossip at Bernarr Macfadden’s New York Evening Graphic (a tabloid commonly called the “Porno-Graphic”), Winchell learned that “the way to become famous fast is to throw a brick at someone who is famous.” He quickly made enemies, namely the Schuberts, who banned him from their theaters. Winchell secured a hefty readership, though, with his euphemistic claims about Jazz Age New Yorkers. Soon enough, he was rubbing elbows with Ernest Hemingway, Al Capone, and plenty of others who feared and respected his power of the press. He regularly attended Manhattan’s Stork Club, where anyone who was anyone knew to find him.

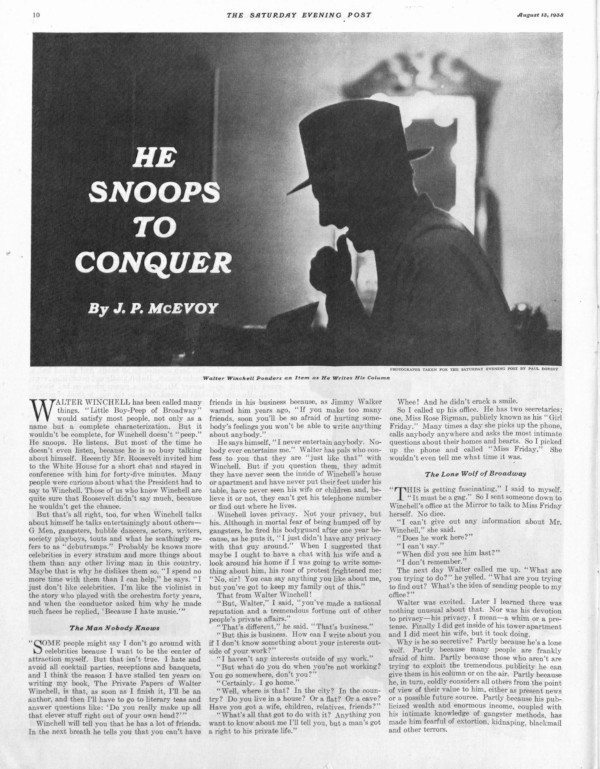

J.P. McEvoy turned a journalistic eye onto Winchell and his brand of “personal journalism,” writing the profile “He Snoops to Conquer” in this magazine in 1938. “Because he was fearless, talented, tireless and tormented by an unappeasable itch for success,” McEvoy wrote, “he arrived at his present peak — where he lives in a state of ingenuous surprise that he has arrived and a gnawing fear that he cannot remain.” Winchell was making about $300,000 a year at the time, between movies, radio, and his column at the Daily Mirror, which was syndicated to thousands of papers across the country. He had become famous for, among other things, coining provocative slang many called “New Yorkese.” H.L. Mencken, in The American Language, noted Winchell’s introduction of several words and phrases into the lexicon. Reno-vated (divorced), obnoxicated, Hard Times Square, intelligentleman. A young couple might be cupiding or “makin’ whoopee.”

Winchell’s reports weren’t limited to celebrity gossip, though. He was an early, outspoken critic of Nazism, taking shots at Hitler as a “homosexualist” called “Adele Hitler” (“he put a hand on a Hipler … ”) and regularly blasting antisemitic Nazi propaganda. When a German-American man named Fritz Kuhn began rallying Nazi sympathizers, first in the Friends of New Germany and later in the German-American Bund, Winchell found a nearer target for derision (“the SHAMerican”). Kuhn thought of himself as a sort of “American Führer,” organizing youth camps and rallies with the growing Bund in the ’30s. Right before more than 20,000 Nazis and Nazi sympathizers descended on Madison Square Garden in 1939 for George Washington’s birthday, Winchell tore into “the Ratzis … claiming G.W. to be the nation’s first Fritz Kuhn … There must be some mistake. Don’t they mean Benedict Arnold?” Winchell was delighted when Kuhn was sentenced to prison for embezzlement that year, writing about how the warden would be “the chief sufferer.”

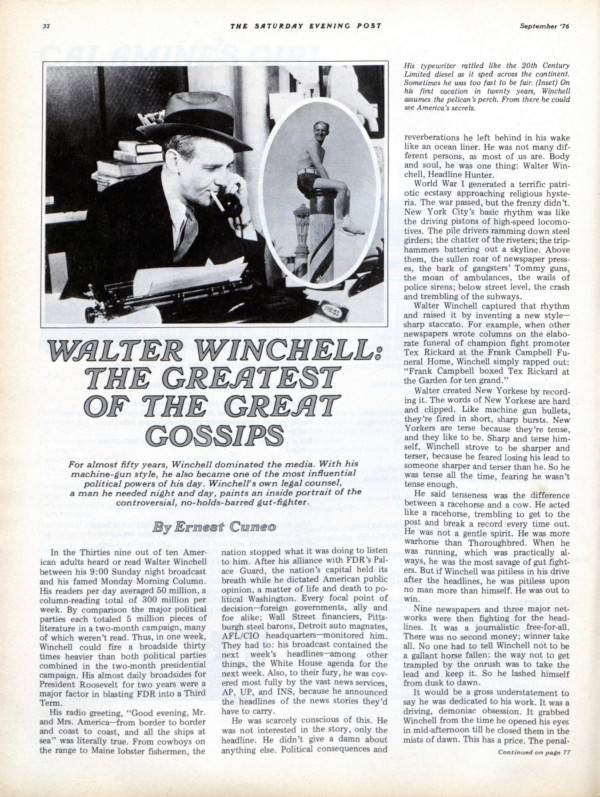

At the start of President Roosevelt’s first term, Winchell praised the president as “the nation’s new hero,” sparking a close relationship with the administration that would prove fruitful for both of them. Years later, Post editor and former Roosevelt liaison Ernest Cuneo wrote all about how prominently Winchell had figured into their strategy to get FDR a third term (“Look, Walter,” I wanted to say, “you are the Third Term campaign.”).

Winchell was taken with President Roosevelt — and perfectly happy to act as a patriotic mouthpiece for the New Deal and American intervention in the war — but after Roosevelt left office, the gossip reporter found himself politically stranded. In 1951, Winchell affronted African-American performer Josephine Baker when he failed to defend her allegations of racism at his beloved Stork Club. Then, in 1954, he frustrated public health efforts by incorrectly announcing on his broadcast that a new polio immunization “may be a killer,” contributing to a dangerous anti-vaccination backlash. Winchell was really sunk, however, after he aligned himself closely with Joseph McCarthy and Roy Cohn.

“If he thought there was a star he could hitch himself to,” Loeterman says, “that was more important than the politics or any of the rest of it.”

Winchell transferred his disdain for Nazism into the anti-Communist witch hunts of the ’50s. He had vocalized his opposition to communism throughout his career, but McCarthy and Cohn made him an honorary member of a new — doomed — club. As Gabler put it, “he would lose because his populism had transmogrified into something cruel and unmanageable, just as his detractors had charged. Once a lovable rogue, Walter Winchell had become detestable.” He had brief stints on television in the ’50s, but nothing stuck. Winchell’s newspaper and radio routines were things of the past, and he had cultivated too much public distrust.

Although he faded from the public eye, Winchell’s mark was already made: the “welding” of news and entertainment. Two years after his death, People magazine was launched, and no shortage of commentators and gossips have haunted our screens and papers since. Kurt Andersen wrote in the Times about the evolution of Winchell’s personal journalism, “As star columnists leveraged their columns to accumulate personal celebrity and their personal celebrity to generate more readers, the market for their sort of journalism grew.”

If Winchell isn’t remembered, then he ought to be, if only so that we can more clearly understand that clickbait has a snappy, five-foot-seven predecessor who was one of the most famous men of his time.

Featured image taken by Paul Dorsey, The Saturday Evening Post, August 13, 1938

The Centennial of Mickey Rooney, America’s Most Persistent Performer

Today is the centennial of the birth of Mickey Rooney, the once-golden boy of Hollywood with likely the longest-running career of any American (or otherwise) film actor.

After beginning his lifelong stint in show business in a specially-tailored tux in his parents’ vaudeville shows at 15 months old, Rooney landed his first film role at age 6 and didn’t stop until 2014, the year he passed away.

The America of Rooney’s films at the height of his celebrity – when he played the lovably well-intentioned troublemaker Andy Hardy in 16 movies – was The Saturday Evening Post’s America: one with a freshly-ironed moral fabric and joyful endings. In fact, Rooney was a Post boy. As the Post bragged in a short piece in 1942, the actor won a medal at age 13 for selling magazines door-to-door and even at the studios where he made his Mickey McGuire movies: “Andy Hardy, as portrayed by Rooney, more often than not engages in financial enterprises that backfire, but in real life Rooney got away to a fast business start with no adolescent detours.”

The Post’s coverage of Rooney wasn’t always so laudatory, however. By 1962, he was just another example of “moral decay in America” as an editorial shone light on his multiple nasty divorces and thousands in back taxes. “Nothing in this sad story surprises us, Hollywood being the way it is,” the Post printed, “but we remember Andy Hardy.”

The now-familiar arc of the innocent child star becoming a frighteningly flawed adult perhaps began with Rooney’s departure from the saccharine cinema of the Hardy family into the trappings of wealth and fame. But he couldn’t play Andy Hardy forever, and he didn’t want to.

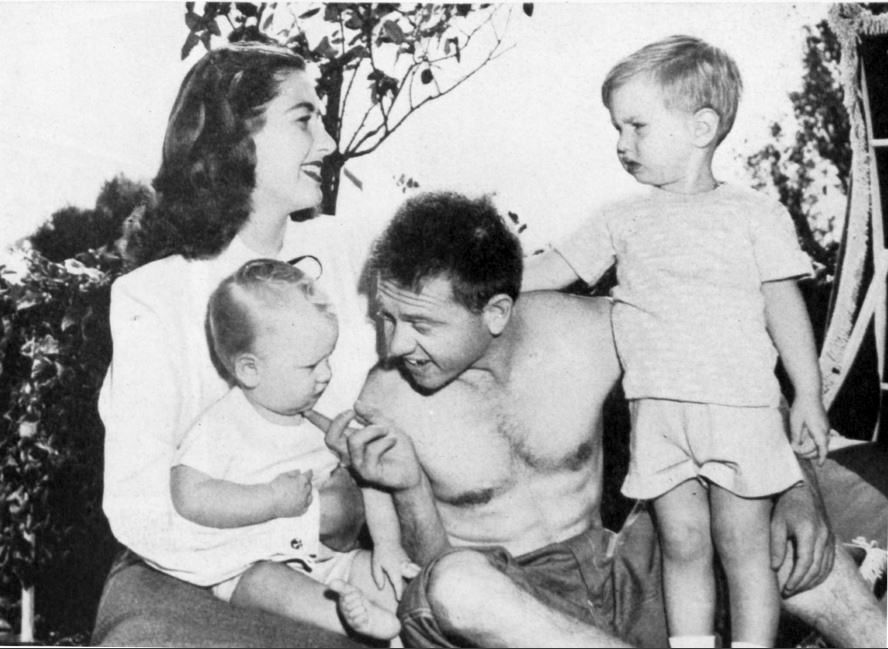

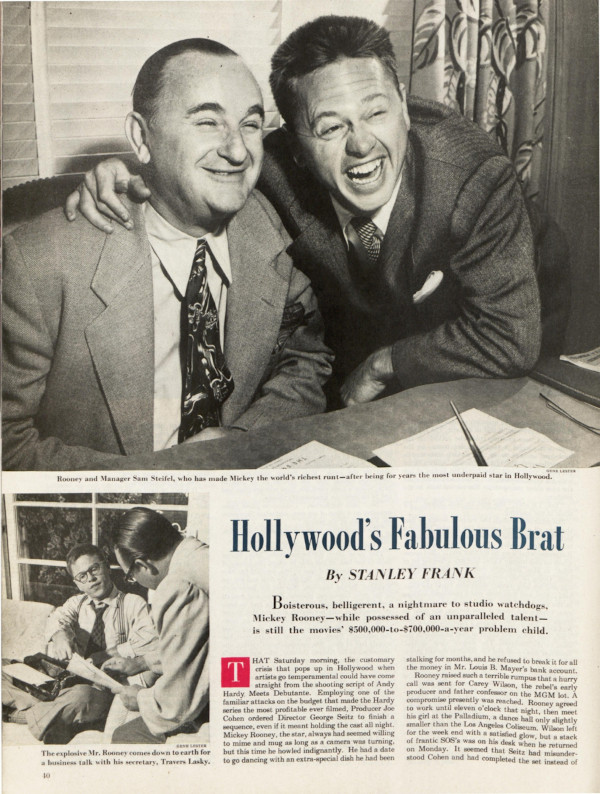

In 1947, the year after Rooney’s last film as Andy Hardy (with the exception of the 1958 revival), the Post published a lengthy profile of the actor called “Hollywood’s Fabulous Brat.” Rooney had spent three years – 1939, ’40, and ’41 – as the biggest box office draw in Hollywood, and he had a reputation for being belligerent, on the set and off. He was also seeking more substantial work.

“I’ll never make another Hardy picture,” he told the Post, incorrectly. “I’m fed up with those dopey, insipid parts. How long can a guy play a jerk kid? I’m 27 years old. I’ve been divorced once and separated from my second wife. I have two boys of my own. I spent almost two years in the Army. It’s time Judge Hardy went out and bought me a double-breasted suit. With long pants.”

Rooney wanted to stretch his wings as he had when he played Puck in Warner Brothers’ A Midsummer Night’s Dream in 1935, when The New York Times reviewed his “remarkable performance” as “one of the major delights of the work.” He wanted to enter into a new chapter of complex films like the forthcoming gritty boxing drama Killer McCoy and the Eugene O’Neill-adapted musical Summer Holiday. After the decades-long run of Hardy family movies and musicals with Judy Garland, however, Rooney’s box office draw dwindled.

Since conquering the motion picture industry with nothing but talent and grit, Rooney couldn’t have foreseen a future where he wasn’t at the top. He imagined he could reinvent his career with the same momentum he always had. As Nancy Jo Sales wrote in Vanity Fair after Rooney died in 2014, “his career suffered from his juvenile appearance, and his diminutive height — he wasn’t a boy anymore, and he wasn’t a leading man, so where did he fit in? — but he never gave up.” Rooney kept making films into the 21st century, delivering memorable performances in movies like The Black Stallion and It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World. In 1979, he took on Broadway in the successful revue Sugar Babies, spawning years of tours.

Rooney’s undeniable talent steered him toward a lifelong commitment to entertainment. Given his start in the demanding realms of vaudeville and the old Hollywood studio system, the performer never hesitated to master new skills, like banjo-playing or crying on demand, to satisfy his audience. This was perhaps never more true than in 1941, when Rooney performed at President Roosevelt’s Inauguration Gala.

Alongside talents like Charlie Chaplin, Ethel Barrymore, and Irving Berlin, Rooney was expected to contribute an act of celebrity impersonations. He had a better idea: he would play his three-movement symphony Melodante on piano instead. As the Post reported, “The audience of 3,844 celebrities laughed when Rooney sat down at the piano that evening and shot his cuffs as he poised his hands over the keyboard.” They thought he was doing a bit. After he played the 19-minute score he had written himself, however, they burst into applause.

For Rooney, the label “triple threat” was an understatement. Starting from a poor broken home, he gave everything he had to build his iconic career, but it never turned out exactly the way he wanted. “People look at me and say, ‘There’s a lucky bum who got all the breaks,’” he said in 1947, “Yeah, I got the breaks — all in the neck.”

Featured image: Gene Lester, The Saturday Evening Post, December 6, 1947

Tom Selleck Riffs on Fame

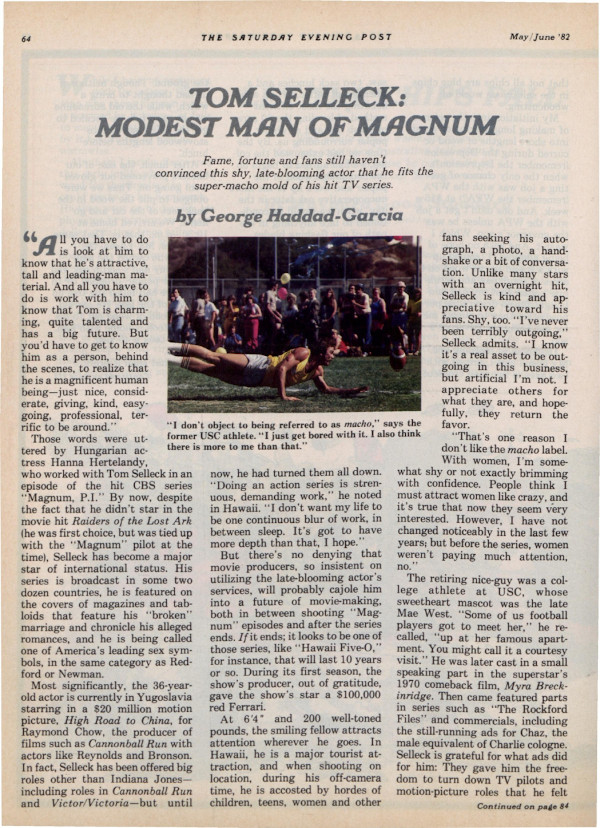

—From “Tom Selleck: Modest Man of Magnum” by George Haddad-Garcia, originally published in the May 1982 issue of The Saturday Evening Post

“I think my biggest problem has always been being taken seriously. I walk into a casting office and I’m tall, and I imagine they say to themselves, “Who is this big, dumb guy? What’s he trying to do, get by on his appearance?” And lots of people resent it — but they should be resenting Mother Nature.” …

“I’ve never been terribly outgoing. I know it’s a real asset to be outgoing in this business, but artificial I’m not. That’s one reason I don’t like the macho label.” …

“People think I must attract women like crazy, and it’s true that now they seem very interested. However, I have not changed noticeably in the last few years; but before the series, women weren’t paying much attention, no.” …

“I’m still the same guy who did television commercials for Pepsi Cola at $250 a shot.”

This article is featured in the September/October 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Courtesy CBS

3 Questions for Michael Caine

For The Saturday Evening Post, I’ve talked to the biggest and the best — the world’s most interesting, influential, and talented famous faces. I’m always asked about favorites. Right at the top of that list is Michael Caine. The best storyteller: He can mesmerize a table of A-listers like nobody else. A spectacular actor: Caine brings charisma and truth to a character with a mastery that only a few screen stars possess. Fans across generations adore him, yet this legend has a relationship with fame that is straightforward and down to earth. In his books and in person, he shares a sly wisdom that always leaves me laughing and thinking.

At 87, he’s still ready to step in front of the camera to play parts he can’t resist. You’ll see him in the upcoming Tenet, an action epic with a twist of time traveling from Christopher Nolan, who considers Michael a good luck charm as well as acting genius, and Best Sellers, a bittersweet comedy about an cranky, aging author. I’ve often asked Michael, with all that’s come his way, how much does he credit hard work and how much does he bow to good fortune? He says, “I gave God a hand.”

Jeanne Wolf: You seem to slip so effortlessly into every character you play but I know how very serious you are about your work. Does the intense dedication pay off as you hide the effort?

Michael Caine: If you’re watching me in a movie and you say to your companion, “Isn’t Michael Caine a wonderful actor,” then I’ve failed. You shouldn’t be noticing the acting. You should be wondering what’s gonna happen to the guy I’m playing. The art is to make yourself disappear.

There are actors who hold up a mirror and say, “Look at me.” I hold up a mirror and say, “Look at you!” My acting should be so human that you say, ”How did he know that about me?” What you should get from my performance, to quote Edmond Wilson, is a “shock of recognition.” I want people to see me on the screen me and say, “I am him.” They know if they met me in the street, I’d talk to them. I wouldn’t be in a limousine flashing by with two blondes and a bottle of champagne. Although, mind you, that’s not a bad idea.

When actors are nervous, it can screw up a scene because it will make the audience feel uncomfortable. I’m often kidding and joking right up to the minute when they call “action.” With me you feel comfortable because I make it look like it’s a walk in the park. But that can be a double-edged sword. It’s like watching Fred Astaire dance. People may think, It’s a breeze. I could do that. Believe me, it isn’t as easy as it looks. It’s like a sort of drug in a way. It’s getting it absolutely right and knowing you’ve done it and you couldn’t do it any better. Sometimes I say to the director, “If you want it any better, you’re gonna have to get someone else cause I can’t do it better than this.” And if you get to that stage, you know, it’s great.

JW: You’ve written a book about acting, yet you’ve said that watching films and doing films was your own best teacher. So what do you tell your young co-stars about what you’ve learned?

MC: I always used to ask old successful actors for advice. Every single one of them said, “Give up acting.” So I say to young actors, “Don’t ask me for advice. The worst thing is it’s free. If you had to pay for it, it might be worth something.”

Early on I took everything because I had no money and I came from a very poor family. Once I started making movies, I thought no one was going to offer me another one so I always took the next one. Finally, I realized I could stop that. From then on, the mistakes I made in choosing roles were genuine mistakes. I thought it would be a good movie and it wasn’t. That was that. But then you get to another period where you don’t have to work. I only do things that I absolutely cannot refuse. I could not refuse Phillip Noyce offering me The Quiet American. I couldn’t refuse being Austin Powers’s father, or Sandy Bullock’s beauty mentor, and, of course, the butler in Batman. One thing now is I don’t get the girl, I get the part. When I used to get the girl, she’d be the most beautiful. Now I get the most beautiful part.

JW: You have a wonderful marriage. You and Shakira Baksh have great joy together. Has experience taught you how to savor your rich personal life?

MC: I live life to the fullest every day. I believe in that. That’s my basic philosophy. Because this is not a rehearsal. This is the show. We’re not opening next Thursday; this is it, we open today. However old you are I think you have to make the most of your life. And I do. There isn’t a day passed where I don’t try to do something. They nearly retired me once, but I came back.

I have this photograph on my sideboard in my dining room. There are three achievements. There’s one of my holding an Oscar. There’s one of the Queen knighting me with the sword actually touching my shoulder. The other is me standing at the top of Sydney Bridge in Australia after an arduous climb.

I wasn’t a success until very late in life. I never made my first big proper movie until I was 29. I was already set in a very concrete way into the person I was going to be, so nothing ever fazed me. Maybe it started with my mother. My father, who was my role model, went away to the war in 1939. I was six. My mother didn’t say, “Oh, now I have to look after you on my own.” She said, “Now Michael, you have to look after me.” So she made a small man of me. I became my father, which stayed with me for the rest of my life. Looking back, I always figure that I’ve been very, very lucky, and I’m just in awe of how lucky I have been — not what I’ve done. That’s why I don’t gamble. I haven’t got any luck left.

This is the full version of an interview that ran in the July/August 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Denis Makarenko / Shutterstock.com

How Tom Jones Has Reinvented Himself for 55 Years

Some performers make a splash and fade quickly. Others have long careers that taper off. The Welsh singer born Thomas John Woodward, known around the world as Tom Jones, boasts one of the longest careers in music, with divergences and new permutations that keep him in the spotlight year after year. He’s reinvented himself when the need has arisen, and he still knows how to swing the lead. The fairly remarkable career of Tom Jones began in earnest 55 years ago today with the release of his debut album, Along Came Jones, or, as it’s since been retitled, It’s Not Unusual.

Born the son of a coal miner and his wife in 1940, Woodward got interested in singing at an early age, performing at school and weddings. Tuberculosis kept him bedridden for the better part of two years beginning when he was 12, during which he spent a great deal of time listening to music. In his teens, Woodward cultivated a number of his early blues and American rock and roll influences, including Elvis, Little Richard, and Jackie Wilson. When his girlfriend, Linda, became pregnant when they were 16, the two married.

Tom Jones performing “It’s Not Unusual” on a 1968 return visit to The Ed Sullivan Show (Uploaded to YouTube by The Ed Sullivan Show)

By 1963, he was fronting a band called Tommy Scott and the Senators. Gordon Mills, a manager out of London, saw the group and recruited the singer, taking him to the city and giving him the stage name “Tom Jones.” Mills enabled Jones to land a deal with Decca Records; his second single, released in January of 1965, would become the centerpiece of his first album and an international hit. That song was “It’s Not Unusual.” It went to #10 in the U.S. and #1 in the U.K. The press lumped Jones in with the ongoing British Invasion of groups like The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, and Jones was soon appearing on American television. His May 1965 appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show was timed with the release of the Along Came Jones album, which hit stores on May 21, 1965.

Mills made quick work of getting Jones in front of audiences across media. He set Jones up to sing the title tunes for the films What’s New, Pussycat? and the James Bond installment Thunderball. Jones won the Best New Artist Grammy in 1966. Around this time, Jones began shifting his repertoire, singing songs that would qualify as rock, blues, country, or easy listening as the venue or notion suited it. The strategy kept him from being tied to a single style and kept him active on the charts in a number of countries.

Tom Jones dueting with Janis Joplin on This is Tom Jones in 1969. (Uploaded to YouTube by Tom Jones)

In 1967, Jones “discovered” Las Vegas as a lucrative recurring performance location. By then, he’d become good friends with Elvis and the two frequently met up in the city. In a 2015 interview with Rolling Stone, Jones recalled meeting Elvis; he said, ““He said to me, ‘How the hell do you sing like that?’ And I said, ‘Listening to you, for one thing.’” Over time, Jones would focus more on the financially rewarding big ticket shows and less time in the recording studio. Between the late 1960s and 2011, Jones performed at least one show in the city every week. In 1969, Jones crossed over to television success with the variety program This is Tom Jones, which lasted until 1971.

Tom Jones and Art of Noise’s video for Kiss (Uploaded to YouTube by Art of Noise)

Jones saw his popularity wax and wane in the 1970s, but he scored lasting hits like “She’s a Lady” and “Say You’ll Stay Until Tomorrow.” For the first half of the 1980s, Jones focused on country music, producing a number of hits in the genre. After Mills died in 1986, Jones’s son Mark took over the singer’s managerial duties. Jones re-emerged on the pop charts in a big way in 1988 when he teamed up with the synth group Art of Noise to cover Prince’s Kiss. The song went Top 40 in the U.S., Top 5 in the U.K., and won Jones and Art of Noise the MTV Video Music Award for Breakthrough Video for their effects-laden clip. The following year saw Jones receive a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Jones was also introduced to yet another generation of fans when “It’s Not Unusual” became the official song of “The Carlton” on The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air; Jones even made a guest appearance on an episode.

“If I Only Knew” received significant MTV airplay in 1993 (Uploaded to YouTube by Tom Jones)

Even with the huge changes in music in the 1990s, Jones managed to stay current. His album The Lead and How to Swing It was a hit in 1993. He played himself in a memorable scene in Mars Attacks! and continued to record music for films like The Full Monty. His 1999 duets album Reload included partners like his contemporary Van Morrison, but also younger acts like Stereophonics and Portishead; it sold 4 million copies around the world, went #1 in the U.K., and served up five U.K. Top 40 singles. Jones never slowed down in the 2000s, and was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in 2006 for contributions to music. In a 2016 interview with The Washington Post, Jones talked about his substantial amount of cover songs and how he interprets other people’s work; he said, “You can’t lose the essence of a song. I try to enhance it more than anything else. Some of them are similar to the original, but not a copy . . . You’ve got to kick them around a bit to see what can you add to it or do something different to it, so you’re just not copying something somebody has already done.”

Jones surprises The Voice U.K. audience with a familiar tune (Uploaded to YouTube by The Voice UK)

Since 2012, Jones has been one of the coaches on the popular U.K. version of the singing contest show The Voice. Jones’s wife Linda, Lady Woodward, died in 2016 from cancer. Though Jones famously philandered through many years of their union, they had remained married for 59 years. Their only child was Mark, though Jones did father another son during an extramarital affair in the 1980s.

Tom Jones occupies a unique space in the musical continuum. He’s sold over 100 million records and has produced work that extends to nearly every popular genre, including gospel. He’s released an impressive number of albums and singles, but those numbers pale compared to the sheer amount of live performances he’s done in his career. He’s shown a mad talent for reinvention that’s only outmatched by the power of his still mighty baritone. It’s tempting to ask what he might do next, but it’s not unusual for Jones to do the unexpected.

Featured image: Fabio Diena / Shutterstock.com

Harry Belafonte’s Image Problem

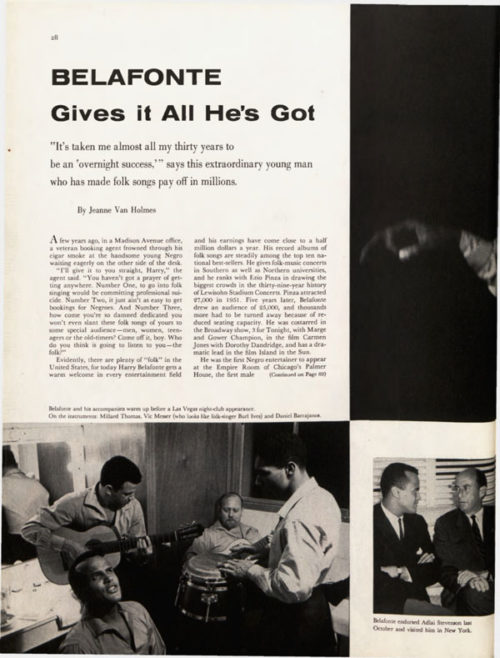

—“Belafonte Gives It All He’s Got”

by Jeanne Van Holmes, April 20, 1957

“I’ll give it to you straight, Harry,” the agent said. “You haven’t got a prayer of getting anywhere. Number One, to go into folk singing would be committing professional suicide. Number Two, it just ain’t as easy to get bookings for Negroes. And Number Three, how come you’re so damned dedicated you won’t even slant these folk songs of yours to some special audience — men, women, teenagers, or the old-timers? Who do you think is going to listen to you — the folk?”

Evidently, there are plenty of “folk” in the United States, for today Harry Belafonte gets a warm welcome in every entertainment field, and his earnings have come close to a half-million dollars a year.

The critics, perhaps a little unnerved by his way of “singing as if his life hung in the balance,” have tagged him as “incandescent” and “irrepressible.” Harry himself put it this way: “I’d say it has taken me almost all my 30 years to be an ‘overnight success.’”

This article is featured in the March/April 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: © SEPS

3 Questions with Patricia Heaton

Patricia Heaton has relived moments from her own life as a mother playing a TV mom on the hugely popular sitcoms Everybody Loves Raymond and The Middle. Now the Emmy and SAG Award winner is imitating aspects of her life again in the CBS comedy Carol’s Second Act. Dressed in scrubs, she’s is an empty nester pursuing her dream of becoming a doctor. “My own four sons are pretty much out of the house,” she says, “and I was wondering what might come next. So it’s been interesting to have this experience with Carol who’s working with interns who are half her age.”

Taking on a new role in her TV career made Heaton realize the potential in all of us to find ways to change direction. That led her to write Your Second Act: Inspiring Stories of Reinvention, due in bookstores in May. “I found stories of some really fascinating people who’ve reinvented their own new lives,” she says. “I think that the book will encourage and inspire a lot of people.”

Jeanne Wolf: Why are second acts so important?

Patricia Heaton: For people whose kids have left home or maybe they’ve retired, it can be a challenge to adjust to a new way of living. I want to encourage them to look inside themselves and to see where they’d like to be in the world at this stage. The world needs all of us. As for me, I’m in Oklahoma producing my first movie. Finding so many things to learn. It’s crazy. And, very important, for a couple of years now, I’ve been a celebrity ambassador for World Vision, which provides relief and aid to children and their families in nearly 100 countries.

JW: Does your sense of humor and having built a career on being funny on television help you cope with whatever life brings you?

“Most real comedy comes from pain. You try to find humor in the troubling situations.”

PH: I think especially in the darkest part and the most difficult times, you just must see the humor and the irony in crazy things that happen. Most real comedy comes from pain. You try to find humor in the troubling situations.

JW: Do you ever think, “I can’t believe the life I’ve led as the star of those iconic TV comedies?”

PH: Every single day I feel that way. I tried to make it in New York for nine years, and I couldn’t get arrested. It’s shocking to me even now that when I came to Los Angeles I didn’t have a car or an agent or a manager. It’s miraculous that I’m sitting there today, having done all the things I’ve done.

Even with success, I think my own ego was getting in the way. I finally realized I needed to step aside and let a greater power take control. I realized I needed to be pursuing it because it’s what God intended for me to do on this planet. And once that dawned on me, I kind of let go and said, “Okay, you lead me,” and things started falling into place.

Of course, an actor never wants to stop acting. It all started when I was in second grade, seven years before I lost my mom to a brain aneurysm. I told Sister Delrina I could sing the entire Color Me Barbra album, and I did for my class. But I know the truly important things in life are your family and friends. I think about what people will say at my funeral. Will it be that you had fabulous ratings and won some big awards? Or that you were a good and kind person. I hope it’s the latter.

This is the full version of an interview that ran in the May/June 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Joe Seer / Shutterstock.com

3 Questions with Patrick Stewart

Patrick Stewart looks absolutely splendid. He smiles at the compliment. “It’s a tribute to my peasant genes.” Stewart admits that being a self-declared workaholic is part of the secret to seeming more than a little like the Captain Jean-Luc Picard from 25 years ago. Now, he’s bringing him back for CBS All Access on Star Trek: Picard in a startlingly new take on the futuristic world.

Stewart made his debut in a school play at six and has never stopped working, on screens big and small as well in theaters around the world. At 79, he can look back on a career in which he’s played nearly every Shakespearean legend and a stunning array of memorable characters in too many movie and TV shows to count, but Sir Patrick is probably most proud of being knighted by the Queen. Stewart reveals that the biggest challenge he faced in his new venture was making sure that Star Trek moved into a future which reflects changes even Gene Roddenberry hadn’t imagined.

Jeanne Wolf: You had some very strong opinions about what you wanted Star Trek fans to see before you took on the challenge of a new series, didn’t you?

Patrick Stewart: I wanted diversity. Many years have passed since the last time I was on a Star Trek set. The world is a different place. So we find our beloved Picard in a life which bears no resemblance whatsoever to his service as a Starfleet captain.

“There’s always an improvement that can be made for humankind and society.”

As for taking on a new challenge, I have never thought of retirement. Sigmund Freud said, “The two most important things in a life if you want to be happy are love and work.” I am very blessed that I have the former, perhaps in ways I’d never have anticipated. However, the work has always been a bit more negative because I’m obsessive. People have said to me, “The problem with you is that you only know how to work, and when you’re not, you don’t feel as though you’re Patrick Stewart at all.” In a sense, that is true. With acting, when I first dipped my toe into that particular creative pool, I was delighted to discover that I could spend a lot of time not being Patrick Stewart, which gave me a great deal of satisfaction.

I sometimes look back and think, How did this all come about? All I wanted to do was be on stage reciting Shakespeare and nothing else, and then suddenly I find that I had become somebody that I still don’t quite know how to be.

JW: What has shaped you both personally and as an actor?

PS: I didn’t have an idyllic childhood, although I started doing some acting at a very young age. My education was over at 15. In the society that I grew up in, you went to work after that. It was usually in a factory, mill, or coal mine. That was where most of my family, after primary school, ended up — and quite a few of them went to prison as well. I was blessed to have one significant person standing at my side, my English teacher, Cecil Dormand. He’s 96 and still doing great. We still have wonderful conversations, and he talks to me like I’m 15 sometimes. Cecil was the one who encouraged me and pushed me in the right direction. We all need someone like that.

And I inherited something from my father. Actually he was an incredible man — a soldier, the most senior noncommissioned officer of the parachute regiment. There was always optimism in the things he expressed. That’s why I felt so connected to Jean-Luc Picard, because he always looked for a better way and improvements that could be made. I’ll never forget one fan letter I got from a police officer who said he loved his job but there were days when he came home stressed and depressed, feeling there was no future at all for any of us. That’s when he’d get out a DVD of Next Generation and watch it and be assured that he was wrong. There was a better world waiting for us. There’s always an improvement that can be made for humankind and society. That, I still passionately believe in, I just think it’s going to be a very difficult few years until we get to that place again.

JW: After some years together, you married singer and songwriter Sunny Ozell. What about love and marriage; has that become simpler even though she’s half your age?

PS: Yes. In the sense that I now think I understand the importance and significance of sharing life with one other person in particular. It’s a glorious gift. The communication between two people from massively different backgrounds like my wife and I brings out in me a reassurance and happiness that, quite frankly, I never thought I would experience. So much joy. Fun doesn’t begin to describe it. Joy would be closer to the experience.

—Jeanne Wolf is the Post’s West Coast editor

This is an expanded version of an interview that appears in the March/April 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

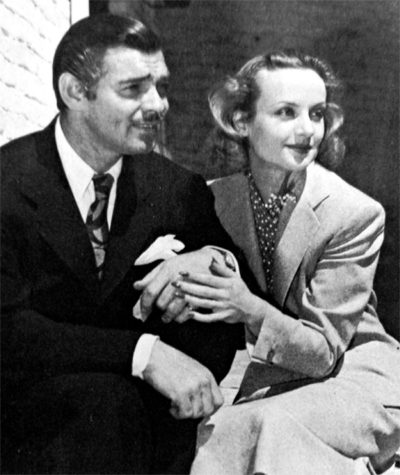

Clark Gable and Carole Lombard: Hollywood’s Greatest Romance

February brings Valentine’s Day and a plentitude of great romance movies: Wuthering Heights. Now, Voyager. Dark Victory. Casablanca. Not that Hollywood hasn’t had it own great romances. Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall. Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy. Frank Sinatra and Ava Gardner.

I would add another, which I remember because I’m 93 (94 next month) and a longtime movie buff — Carole Lombard and Clark Gable.

Perhaps, the greatest of them all.

Equally big stars, she was reportedly the highest paid actress in Hollywood and he was so popular he was dubbed “The King.” A beautiful blonde, the equal of any star then (or since), Lombard played dramatic parts but was best known for her roles in the zany comedies of the mid-’30s, the cinematic antidote to The Great Depression. She had a comedic touch perfect for such classics as Nothing Sacred and My Man Godfrey. Gable, who starred in such films as Test Pilot and Boom Town, was the only actor American readers and movie-goers would accept for the role of Rhett Butler in Gone with the Wind.

They co-starred in the film No Man of Her Own in 1932, but no romantic sparks were sparked. Both were married at the time (although that has not stopped a lot of budding romances in Hollywood). A chance meeting at a party four years later — she was now single again and he was separated from his wife — and the spark was struck. His wife did not want to give him a divorce, but he prevailed, and it was finalized in March 1939. Taking advantage of a break Gable had in filming Gone with the Wind, they eloped to Kingman, Arizona.

One of my most vivid memories of movie stars when I was growing up were the photos that appeared not only in the movie magazines of the day but newspapers across the country of them shortly afterward, at his ranch in Encino, California. I can still see them, smiling happily. And later that year, at the world premiere of Gone with the Wind in Atlanta, in formal dress for the occasion, she is on his arm as they arrive, and he pauses at the microphone to address the crowd and nation through the newsreels of the time, saying, “This is Margaret Mitchell’s night.” But I remember Carole Lombard and Clark Gable.

Undoubtedly, there were other photos and stories.

Then the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. President Roosevelt asked the Congress for a Declaration of War. And, like the rest of the nation, Hollywood and its stars mobilized for the coming fight. In mid-January, between pictures, Carole Lombard went back to her native Indiana on a War Bond Tour. Her mother went along, as did Otto Winkler, Gable’s friend and publicist, whom Gable had asked to accompany Carole on the tour. The tour was capped off by a dinner in Indianapolis the night of January 15, 1942. Carole Lombard had raised more than $2 million. Today, that would be more than $32 million.

They were supposed to return home by train, as the government preferred that stars on bond tours not fly. Also, her mother and Winkler were afraid of flying. But Lombard was anxious to get back to her beloved “Pappy,” her name for Gable, and reportedly didn’t want to face three days on the “choo choo train.” They decided to flip a coin. Lombard won. And they booked a flight on a commercial airline. TWA Flight 3, a transcontinental flight out of New York, made a stop in Indianapolis, at or about 3 a.m. It would get them home late that evening.

It should be remembered that commercial flights were in their early years back then — stagecoaches, if you will, compared to today’s flights. No jets. Propeller driven. No pressurized cabins. Passengers huddled under blankets to keep warm. Frequent stops. Not only for passengers to board or depart but to refuel. During the stop at Albuquerque, New Mexico, Carole and her party were almost bumped to make way for military personnel, who took precedence in wartime. But Lombard pleaded her case, and they were allowed to fly on.

What follows has come to be known as “The Mystery of Flight 3.” It’s known that the plane made a refueling stop at Las Vegas, then a small town. It may be that the pilot mistakenly set a course used for takeoff from Boulder, Colorado, which he and the co-pilot had flown recently. Or the pilot mistook a beacon light to the right of the runway as being at its center and flew to the right, instead of going left. Or that beacon lights that would normally have been used had been turned off, due to the war, lest they attract enemy planes.

Never disputed, the pilot did not realize he had not reached the altitude needed to clear the treacherous Mount Potosi. And there were no air traffic controllers to tell him.

The plane flew into the side of the mountain, killing all 22 aboard.

“Gable rushed to the city, first hoping for a miracle,” as the Las Vegas Review Journal put it, looking back on the 75th anniversary of the crash, “and then keeping a grief-stricken vigil until rescue teams recovered his wife’s remains.”

It’s said he never recovered.

Certainly, the loss is plain to see in the photo of The King being sworn in to the U. S. Army Air Force, as a private after enlisting, August 12, 1942. The pain on his face and in his eyes is seared into my memory. Not the pain in TV shows when someone is trying to get someone else to talk, divulge a name or meeting place. The pain that comes from somewhere deep inside — dare I say the soul? — and stays with you the rest of your life.

The Air Force sent Gable to Officer Candidate School, assigned him to a film unit in Hollywood, to which he brought great credentials, then overseas to film “Combat America,” a propaganda film about air gunners. Official records show he flew five combat missions, but fellow veterans say he flew more.

He may be seen in uniform January 15, 1944 — the second anniversary of the dinner capping Carole Lombard’s War Bond Tour — watching actress Irene Dunne break a bottle of champagne against the bow of a Liberty Ship. The ship was christened the Carole Lombard in recognition of her contribution to the war. The Carole Lombard would go on to rescue hundreds of survivors of sunken ships in the Pacific.

Whether officially or unofficially, the mountain on which she died came to be known as Carole Lombard Mountain.

After the war, Clark Gable returned to Hollywood, resumed his career. In his first film he co-starred with Greer Garson (Mrs. Miniver), prompting the ad line, “Gable’s back and Garson’s got him.” He would make movies for some 15 years, co-starring in his last, The Misfits, with the new blonde star of Hollywood, Marilyn Monroe.

In one of those twists of fate worthy of an O. Henry story or Alfred Hitchcock movie, it would be the last film for both Gable and Monroe. Two days after filming ended, Gable suffered a heart attack, sufficiently serious that he was not only hospitalized but held for further care and observation. There were those in Hollywood who thought it was his frustration with the famed tardiness of Monroe that had driven him to passing the time wrangling the wild mustangs that were part of the film — in the heat of the desert yet — and had brought on the heart attack. And his popularity cast a cloud over Monroe that some say never ended before her death two years later.

Gable suffered a second, fatal heart attack while still hospitalized and died November 16, 1960.

Although he had married twice in the postwar years, and was happily married at the time to a woman about to present him with a son, he chose to be buried alongside Carole Lombard in Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California.

If, unlike Romeo and Juliet, years passed between their passing, their romance may well rank up there with Shakespeare’s classic.

Certainly, the romance has those twists of fate, moments of “what might have been,” thread of tragedy, that make you wonder what The Bard would have done with Clark and Carole.

Featured image: Carole Lombard and Clark Gable in a movie still from No Man of Her Own (Wikimedia Commons)

Dr. Kildare Is a Doll

Originally published in The Saturday Evening Post March 30, 1963

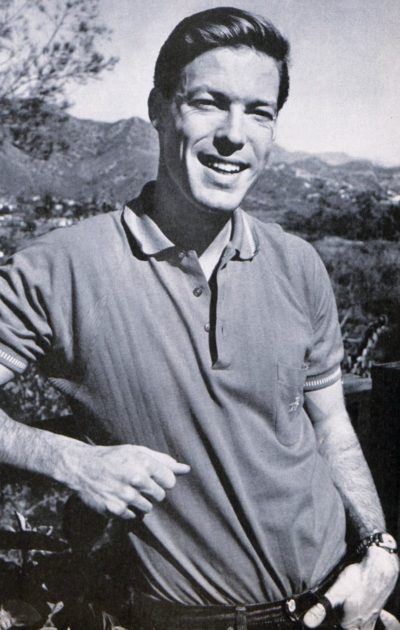

The recipient of more fan mail at MGM than Clark Gable in his prime, Richard Chamberlain courts disaster by merely venturing outside the studio gates. In Baltimore last fall, women beleaguered him in such ravening numbers that the police had to evacuate him to a boat in Chesapeake Bay. In Pittsburgh he required police protection when 250,000 fans mobbed the city’s downtown area during a personal appearance. Girls camp on the doorstep of his two-room bungalow in Hollywood Hills, and it is not uncommon for female fans to waylay him and beg to be taken inside for an examination.

“With a doctor, a woman envisions security, both emotionally and materially,” is the diagnosis of Chamberlain. “But there’s another reason. Kildare looks pure. He is waiting to be taught sin. To women, this is encouraging.”

The Kildare series is the studio’s hottest television property, though Chamberlain frankly is hard-pressed to explain why. He feels that Kildare is an irreclaimable bore.

In the 3,500 letters a week he receives, women open their hearts to him, some discussing intimate medical problems. “You would think this is mail-order gynecology,” says Chamberlain. “My answering service adheres to the ethics of medicine by offering no advice.”

Last September the studio decided to expose Chamberlain to his public for the first time, hardly suspecting the dangers. There followed the riot scenes in Baltimore and Pittsburgh. Then he was shipped off to New York, where one day he decided on a quiet stroll through the Central Park Zoo, hoping to go unnoticed in blue jeans, sneakers, and T-shirt. The attire didn’t fool a teenage girl. She screamed. Soon she was joined by a small squealing mob. One girl slipped her class ring on his finger. Others threw scarves at him. Another, undeterred by the trumpeting elephants nearby, rested her head on his back and moaned rapturously, “Oh, doctor.”

—“Doctor Kildare Is a Doll” by Melvin Durslag, March 30, 1963

This article is featured in the January/February 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Collection Christophel / Alamy Stock Photo

3 Questions with Alan Alda

Alan Alda isn’t exactly resting on his laurels, or resting at all for that matter. He received the coveted Screen Actors Guild Lifetime Achievement Award last year, to add to his seven Emmys, six Golden Globes, and an Oscar nomination for Best Actor in a Supporting Role for Martin Scorsese’s The Aviator. Of course, none of those overshadow his rise to stardom as “Hawkeye” Pierce in the ever-popular, darkly comic ’70s TV series M*A*S*H. He’s currently playing a lawyer in Noah Baumbach’s scorching Marriage Story, now streaming on Netflix, alongside Scarlett Johansson and Adam Driver.

The star has been out front in the battle to find a cure for Parkinson’s disease. He explains, “When I first knew I had Parkinson’s, I waited a couple of years to reveal it. I finally went public because I wanted to help remove the stigma. People who don’t want to admit they have it are holding back the progress we can make to cure the disease. If you get Parkinson’s, your life is not over.”

Jeanne Wolf: You play the voice of logic and kindness in Marriage Story as an attorney acting reasonable in the unreasonable atmosphere of a breakup.

Alan Alda: I didn’t need to do any research to play a lawyer. I’ve been through a lot of lawsuits. I love a good lawsuit. I’ve sued a few of the film studios (but I’m not saying what for). I think some of them thought I was too polite and wouldn’t take them on. You know I’ve always had that nice guy image, but that’s a bum rap. I get angry like everybody else.

JW: Your father, Robert Alda, was an actor. Did he want you to follow in his footsteps?

AA: My father encouraged me by discouraging me. He said, “No, don’t be an actor, it’s a hard life,” and then he tried to get me jobs. I guess I sort of paid him back by getting him parts in several episodes of M*A*S*H. That was fun. The only advice my dad gave me about acting that I can remember is, “Your legs will get tired, so always find a place to sit down.” It’s true. If you watch me on M*A*S*H, you’ll see how often I was sitting down with my feet up on the desk.

JW: I love that you’re working as hard as ever. What keeps you going?

AA: Number one, it has to sound like fun, and it has to seem like it will be a challenge because I don’t want to keep doing what I’ve done before. It’s like walking a high wire between two buildings and seeing if you can keep from falling off. It doesn’t always have to be in front of a lot of people. I’ve gotten as much of a kick out of performing in a small theater before a couple of hundred people as 20 million on TV or in a movie.

—Jeanne Wolf is the Post’s West Coast editor

This article is featured in the January/February 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock.com

3 Questions for Danny DeVito

After almost five decades in show business, Danny DeVito still gets a kick out of seeing himself on a movie poster. For the new live-action Dumbo, directed by Tim Burton, he’s sporting a top hat as the ringmaster of the circus that is home to the famous flying elephant. “I’m very at home in the center ring,” he laughs. “The part felt familiar because when I did Batman Returns with Tim I had a circus troupe.”

The Oscar nominee and Golden Globe winner has taken on roles of ordinary and extraordinary characters like no one else on screens big and small. He’s loveable even when what he does and says should make us cringe. Imagine encountering Taxi’s Louie De Palma in real life — especially in our politically correct environment. And then there’s Frank on It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia: crude, rude, and funny as hell.

Now DeVito is working with Dwayne Johnson on the new Jumanji, and The Rock couldn’t help but gush about his newly minted co-star, saying, “The idea of Danny DeVito joining our cast was too irresistible.”

Jeanne Wolf: I just saw you on Michael Douglas series The Kominsky Method. Do you still go after the best parts, or do they come to you?

Danny DeVito: Both. But actors want to work. Maybe some are thinking about becoming big movie stars, but I always believed the best thing for me was to focus every day on trying to get a job. Moment to moment, you think to yourself maybe you’ll get lucky. Of course, for me, the big break was getting Louie de Palma in Taxi. You don’t know when it’s going to come, so you just want to be ready. What you live for as an actor is to get up there and be with other actors. Now I have the best gig in the world doing It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, which has been around a lot longer than Taxi. But every day I still call my agent and say four words: “Get me a job!”

But acting is not just a job, it’s a craft. My grandfather was a tailor. He could take a piece of cloth and make the most beautiful things. I like to think I’ve got some of that ability to take all the elements and work them into something beautiful, something that will grab people and entertain them. Also, I’ve gotten rid of my worst impulses by acting them out. It started with Louie. It’s like a license to kill. I was given this wonderfully diabolical, self-serving, self-centered character to play.

JW: Did you dare to dream as big as the films and TV shows that have made you a big star?

DD: When I was a kid I used to sit in front of the TV watching old movies and thinking I could do that but I couldn’t really tell my pals what I was planning. That would have been too tough. They would have said, “Danny what’re ya, nuts? Who d’ya think you are, Cary Grant?” So I had to keep my mouth shut. But I was learning about comedy.

My mother and father had what I guess you could call an explosive relationship. Everybody was always saying exactly what was on their mind. Sometimes, being funny was the best way to hold your own, and that can really develop your sense of humor. Now, I’ll do almost anything for a laugh. I don’t want to do any kind of dangerous stunts because I’m a chicken, but I will do anything if it is funny for the script. I’ve gotten thrown out of windows. I’ve been naked. I’ve puffed myself up in a fat suit with makeup. I’ve done everything.

JW: We’re in the middle of an immigrant controversy. Your family were immigrants.

DD: My grandparents came from southern Italy. They lived in cold-water flats in Brooklyn. My grandfather shined shoes. He didn’t have a skill. So it’s like a normal story for immigrants — coming here and not speaking English. They came because they had no money, not unlike the cases of the people from Nicaragua and from El Salvador who are coming to the border. And here we are in this big, beautiful country that has all these legends, like the Statue of Liberty, and it has all this land and is so wealthy. I would come here too. I would do whatever I could to try and get into the country.

But you can’t live in the past. What you gotta do is think of the future because what you’re doing right now is gonna be the good old days. If you sit around on your butt and don’t do anything, when you’re 90 you’re going to have no “good old days” to think about. You’ve got to do it now. You gotta get up and do something. Don’t sit around just listening to all the claptrap on television. Go out to the movies because going out to the movies is an experience in itself. Take a friend, go out to dinner. Don’t drink and drive, but have a good time.

Entertainment, that’s what we do. We are a release. You go into the movies and the lights go down and you become absorbed in the story. It’s like reading a good novel. It takes us from our reality and shows us, in our lives, something that we can hang our hat on and emulate. I like that people leave the theater and have a good smile on their faces.

An abridged version of this interview is featured in the March/April 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Image Credit: Shutterstock.com

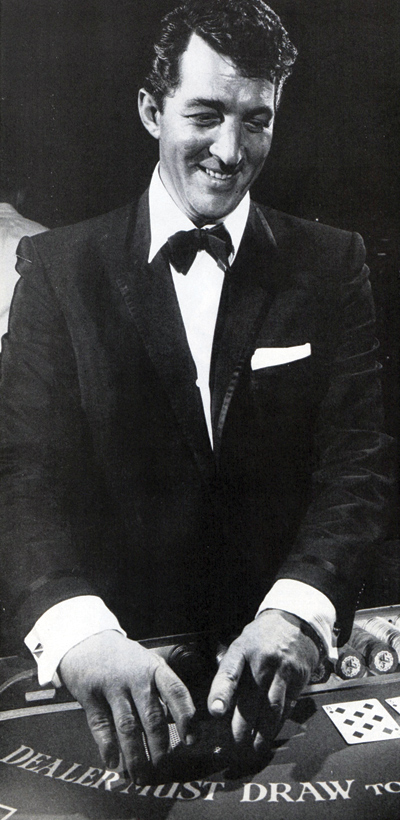

Dean Martin’s Lush Life

Originally published April 29, 1961

“How much do you really drink?” Post interviewer Pete Martin asked.

“About one-tenth as much as I pretend to. I used to really knock the hookers of sauce back, but I gave that up some time ago. Take a typical day here in Vegas. I get up at 11:30 every morning. By 12:30, I’m out on the first tee with three guys I play around with. I’m through about 15 minutes to four. Then I come in and have a sandwich and a bottle of beer. I’d be at the blackjack table and play until about 5:00.

“All that time I’d have nothing to drink except that one beer. Then I go to the health club. A guy gives me a massage, and I say, ‘Wake me at 7:30.’ He wakes me. I put on my clothes while I’m having four cups of black coffee and sugar, no cream. About 8:15 I’m in the casino playing a little more blackjack. I play until 8:30. Then I walk into the dining room, they announce my name, I get up on the stage, and I invariably overhear somebody at a ringside table say, ‘Look at his eyes! You can see how drunk he is.’”

I looked at his eyes. They did sort of droop at the corners.

He went on, “I’ll have a slug of a liquid in an Old Fashioned glass that looks like scotch right in front of everybody, but it’s really apple juice. Then, in the middle of my act, I have a real drink. When I’m through with the act, I go someplace and eat some good Italian food. I have a little wine with that meal, then I get back on stage for the second show. When that’s over, I have three or four or five drinks and maybe a sleeping pill. So that’s your alcoholic for you.”

“All right,” I said, “but you’re a legendary drinker to the public.”

“I’m responsible for that,” he said, “because I’ve joked about it so much on the stage. I don’t want to disillusion people, but it’s been years since anyone has seen me really stoned. I don’t want to throw bouquets at myself either, but I’m 43, and I couldn’t look as young as I do and play as much golf as I do if I drank and cavorted as much as the public thinks.”

This article is featured in the January/February 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Let Me Tell You About Mae West

Originally published November 14, 1964

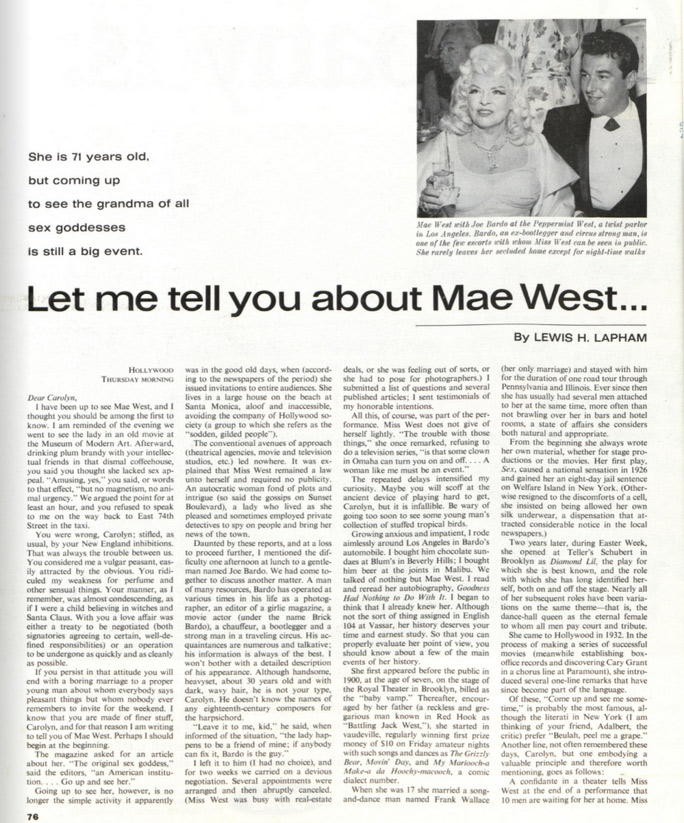

At the age of 71, Miss West still possesses overwhelming sexual force. It comes and goes, like distant music heard across a fairgrounds on a summer night, but it is there. She first appeared before the public in 1900, at the age of 7, on the stage of the Royal Theater in Brooklyn, billed as the “baby vamp.”

When she was 17, she married a song-and-dance man named Frank Wallace (her only marriage) and stayed with him for the duration of one road tour through Pennsylvania and Illinois. Ever since then, she has usually had several men attached to her at the same time, more often than not brawling over her in bars and hotel rooms, a state of affairs she considers both natural and appropriate.

“With me, sex has always been a natural thing, part of my personality, you know what I mean? … I was the first person to bring sex out into the open. Before I came along, nobody could even print the word on billboards.”

She explained that although she had carried on with a number of gentlemen over the years, she had never been promiscuous or cheap; neither had she suffered twinges of guilt or regret.

“The score never interested me,” she said, “only the game.”

—“Let Me Tell You about Mae West” by Lewis Lapham, November 14, 1964

This article is from the November/December 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

An Interview with Reba McEntire

Reba McEntire fans are like her worldwide family, and they share her pride when she garners another accolade. The latest is the inaugural Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame Career Maker Award, and no one but Reba seems surprised that she’s about to be handed a Kennedy Center Honor. “I was flabbergasted,” she declares. “I was just so thrilled. It is beyond entertainment. It’s kind of like you’re the all-around cowboy if you’re in the rodeo. It’s more than just being able to sing.” But it’s the songs from the Queen of Country that have defined her career, selling over 56 million copies and making her one of the best-selling artists of all time.

When she isn’t singing, Reba might be acting, which propelled her TV sitcom Reba to success for six seasons. Its cancellation was a big disappointment, but there is hope that the series might return.

“We’ve kept working on it,” she says, “and right now, the reruns make it the most popular syndicated show next to M*A*S*H.”

When Reba entertains at one of her favorite venues — The Colosseum at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas — with Brooks and Dunn, she not only stops every show, she has to sing a little louder to be heard because those fans are singing right along with her. Always grateful, she insists, “I give the songwriters and the writers of the TV show the credit on all of this, because without the words for me to sing or to talk, I wouldn’t have that gift. It’s a total gift from God. I always say, ‘Let me be the conduit. Let me help in any way I can.’”

In addition to her appearance at the Kennedy Center Honors (airing December 26), she’s also making a return performance as host of the CMA Country Christmas on ABC.

Jeanne Wolf: On your latest album, Sing It Now: Songs of Faith and Hope, you sing about your belief in a higher power. Ever worry that being so open about your faith might seem like you’re preaching?

Reba McEntire: I know what you mean, but my grandma always taught by example. I’m not out to teach or preach; I’m just showing everybody that I’m happy the way I am because of my faith. It’s a relief to me that God is always taking care of me, always helped me through the hard times, and is always there with me in the great times. Music and entertainment seem to be a way to deliver a little message to folks without beating them over the head and preaching to them. It’s very subtle, but it hits the heart. I’m looking in people’s faces when I’m performing, and I know when a song is really touching their hearts. Hopefully, they feel like I am singing it to them. It makes me feel real good that they felt that they got that connection.

Music has helped me in so many different ways. After I lost seven of my band members and my tour manager in a plane crash in ’91, we went to the studio and started recording songs. Leland Sklar, the bass player, said, “Reba, are we going to record any happy songs on this album?” I replied, “Not on this one,” because it was helping me heal my heart. It’s true about my divorce, too. The world doesn’t stop for a broken heart, and that’s the truth. You’ve got to go on, but you’ve got to express your pain, and the way I did it was through my music. The songs I choose, 99 percent of them, are about heartache, and that’s what makes country music so popular. It’s relatable. When a person is sad, they don’t listen to happy songs. I guess misery loves company.

JW: When you and your husband and manager of 26 years, Narvel Blackstock, broke up, you shared your stress and disappointment. Now you’ve introduced your new beau, Anthony “Skeeter” Lasuzzo, at last year’s Grammy Awards.

RM: I think that kind of split is hard on anybody. I’m no different than anyone who’s ever gone through a divorce or a death. Even if you’re in the public eye, the hurt’s the same. I don’t have any secrets, because people pretty much know everything. Time has passed and I’m a happy camper. I have a new love in my life, and I have done things that I couldn’t have gotten to do before, so I’m always a firm believer that timing is everything and everything happens for a reason.

There’s a lot of things I miss. I worry for my family, because a divorce hurts more than just the two people who get divorced. It’s a ripple effect. It’s everybody that is involved. It changes everybody’s lives.

My boyfriend, Skeeter, is a great guy, very open, and we’re having fun together. We’ve been to Africa, Iceland, and Italy this year. I think being very secure in his own skin makes it a lot easier to deal with the things he has to deal with for me. He’s a very confident, secure man, and so he doesn’t have to prove anything to anybody, and we have a wonderful time with all the stuff that we’re getting to do.

JW: What has helped you make it to the top and set such high standards for yourself without letting your fame and success change you?

RM: First of all, my parents. My mama’s a little spitfire. There are about 50 things that I can hear her saying in my mind, but the number one thing is, “I love you gobs and gobs.” Daddy was the strict disciplinarian, a hard-working man with little patience. One of the sweetest things he ever said about me was, “Reba, when I hear people talking about you or when I hear your voice on the radio, my stomach just goes to pumpkin.” And the other was, “Reba, you sure do work hard.” From Daddy, that was a huge compliment.

I’m the first to admit, I’m very competitive. I love to play games, and I love to win, but when I lose, I’m the first one to start clapping and say, “Congratulations, now let’s do it again, because I’m going to whip your butt.” I grew up on a working cattle ranch. My daddy and my grandpap were world champion cowboys. My brother and I were always competing, saying, “Anything you can do I can do better.” You wanted to win, but it was also a game.

People say, “How do you stay so grounded?” I say, “Well, my sister calls me a twinkle, not a star.” I don’t have yes-people around me. I love teamwork. I don’t think anybody is supposed to do everything by themselves. It’s lonely, doing it by yourself, even if you can. But I can be a diva, a big-time diva. My co-star on my TV show Reba, Melissa Peterman, was saying the other day, “I love to see Reba when she puts on that red dress and walks out on stage and becomes fancy. She’s just got a strut to her.”

This article appears in the November/December 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.