Charlie Chan: The Case of the Oriental Detective

Fictional detectives such as Sherlock Holmes and Hercule Poirot have entertained and enchanted audiences for generations. Whether on the screen or page, these characters manage to clear up mysteries while remaining mysterious themselves. Enigmatic, eccentric, or exotic, they intrigued readers as much as the whodunits in which they appeared.

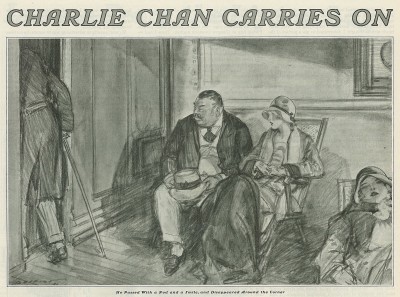

In the 1920s, the Post introduced a new addition to the pantheon of great detectives—Charlie Chan. As conceived by Earl Derr Biggers, Chan used the wisdom of his native culture to outwit criminals and solve cases that baffled others. Chan proved so popular that he eventually appeared in six more serials in the Post. His character was also used in over 50 movies made between the ’20s and ’50s.

Today, though, his popularity has dimmed, and many regard him not as a wise detective from a far-off land but a racist caricature of Chinese-Americans.

How could a loveable character such as this become something so offensive? If you are looking for a simple answer, you might as well stop reading this right now because the issue of Charlie Chan is far from black and white. While the novels may seem offensive today, they were enlightened for their time.

Chan started life as an “oriental;” that is, as a stereotyped character that played on Westerners’ preconceived ideas of Easterners.

Note, for example Chan’s first introduction in “The Keeper of the Keys,”

“The young woman who was bound for Reno felt somehow rather grateful towards him. Presently he turned, and the girl understood, for she saw that he was Chinese. A race that minds its own business. An admirable race. This member of it was plump and middle-aged. His little black eyes were shining as though from some inner excitement; his lips were parted in a smile that seemed to indicate a sudden immense delight.”

Although this introduction paints a romantic image of Chan, it seems to exaggerate his “Chinese-ness,” making him less a person than the product of a far-off land.

This image is reinforced by the witty Chinese proverbs that Chan utters throughout the novels:

“The man-hunting tiger is sometimes over-plump,” he remarked. “Still he pounces with admirable precision.”

However, Biggers must have known that a one-dimensional caricature wouldn’t hold readers’ interest. He made Chan a “West-friendly Chinaman” who lives in Hawaii, which, at the time, was a US territory and a half-way point between the US and Asia. The novels emphasize his Hawaiian home almost as much as his Chinese decent.

In the six years he wrote Chan mysteries, Biggers worked to make his detective a genuine representative of his culture. In his first mystery, “The House Without A Key,” Chan was nothing more than a bit of local charm for the tale’s Hawaiian backdrop. By the time “The Keeper of the Keys” rolled around, however, Chan had become the star of the series. He had also developed unexpected depth, and the author shares Chan’s awareness of the racism around him.

“Even if he’s a Chinaman?” sneered Ryder, but he rose to go.

As Chan followed him up the stairs, hot anger burned in his heart. Many men had called him a Chinaman, but he had realized they did so from ignorance, and good-naturedly forgave them. With Ryder, however, he knew the case was otherwise; the man was a native of the West Coast, he lived in San Francisco, and he understood only too well that this term applied to a Chinese gentleman was an insult. So, no doubt, he had intended it.

It was, therefore, in a mood far less amiable than was his wont that the plump Chinese followed the long, lean figure of Ryder into the latter’s room. The door as he closed it after him might almost have been said to slam.”

Biggers also brought up Chan’s own identity crisis. When Ah Sing becomes the prime suspect, Chan feels uncomfortable investigating someone who is more “Chinese” than himself,

“Mr. Chan,” he said suddenly, “how close can you get to the heart of Ah Sing?”

“It overwhelms me with sadness to admit it,” Charlie answered, “for he is of my own origin, my own race, as you know. But when I look into his eyes I discover that a gulf like the heaving Pacific lies between us. Why? Because he, though among Caucasians many more years than I, still remains Chinese. As Chinese today as in the first moon of his existence. While I-I bear the brand-the label—Americanized.”

While you consider whether Charlie Chan was a caricature, a representative of Chinese culture, or just a fictional gimmick, consider the fact that he became popular among Americans without playing the stereotype of an inscrutable foreigner. And consider the fact that he had been highly popular in China, which has produced several Charlie Chan movies over the decades. Shocking as it may seem, audiences in China actually found Chan to be a sympathetic portrayal of their culture. The Chinese consider his character, as seen in movies, to be positive, not to say brilliant and funny—a definite improvement on the traditional view coming from the West. Many of the older Chinese may remember the string of movies, like Charlie Chan at the Olympics and Charlie Chan at Monte Carlo that appeared during the 1930s. Forgotten now, they once appealed to a variety of audiences. As Chan sleuthed across the silver screen, he was entertaining millions of urban Chinese and winning fans among the British colonials who policed the foreign zone in Shanghai—the same colonials who had hung a sign over the entrance to a park that read, “Neither Chinese Nor Dogs Allowed.”