Was the American Chestnut Completely Wiped Out?

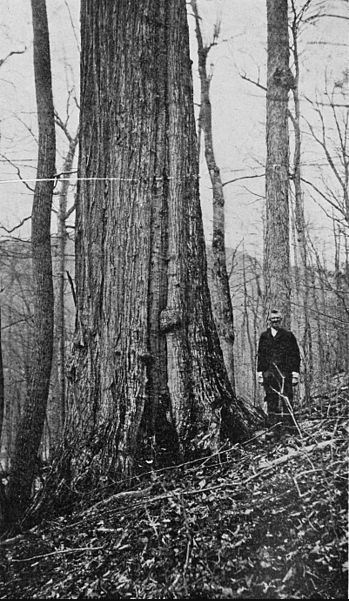

An Arbor Day observance would seem incomplete without a celebration of the majestic American chestnut. The tree is ingrained in our heritage, from the sweet, nutritious nuts “roasting on an open fire” to the sturdy, rot-resistant lumber that built our railroads and fences. From Maine to Mississippi, the American Chestnut once comprised up to 25 percent of the Appalachian forests. Early settlers admired these hardwoods that stood nearly 100 feet tall — that is, until we wiped them out.

The chestnut blight was first noticed by a forester in the Bronx Zoo in 1904. By the 1950s, the fungal disease had spread to Georgia, girdling every American chestnut in its path — an estimated four billion trees. The fungus was thought to have been introduced by way of chestnuts imported from Japan in the 1870s. These Asian varieties were resistant to the disease that devastated the eastern forests of the United States.

In a 1925 Post article, “Adventures in Planting,” Robert Gordon Anderson grimly predicted the chestnut blight: “Starting in New England some years back, it swept over the Hudson like an invisible prairie fire and so on to the West, making our American chestnut almost as extinct as the dodo; it will probably vanish quite as completely within the next 75 years.” As it turns out, Anderson’s prescient account underestimated the virulent fungus by about 50 years.

One question remains: Are there any American chestnuts left?

Many of the infected trees sent up shoots from surviving root systems after their demise. Unfortunately, these suckers succumbed to the same fungus after about 10 years — or 20 feet of growth. There are, however, many accounts of thriving American chestnuts in Michigan, Wisconsin, and the Pacific Northwest. These humble stands of trees could not possibly compare to the swaths of forests that once towered over a significant part of the country, but it’s a start.

The American Chestnut Foundation is a national nonprofit that collaborates with State University of New York to attempt a reintroduction of the tree to its original habitat. To accomplish this, the ACF is involved in continual research of the best way to utilize fungus-resistant properties of the Chinese chestnut in a hybridization with our beloved American chestnut. The research is slow-going because trees are slow-growing, but SUNY thinks they may have found the answer in transgenic trees. These are chestnuts that have been genetically altered by inserting one wheat gene into the genome of the American chestnut. That gene can help the tree fight oxalic acid — the toxin produced in chestnut blight.

Ruth Goodridge of ACF says they hope to crossbreed their hybrids with SUNY’s transgenic trees once approval is obtained from the USDA, EPA, and FDA. Since the organizations will be completing applications later this year, that approval could come by 2021.

“We hope to plant them everywhere. This is about the restoration of an ecosystem,” Goodridge said. She noted their interest in promoting biodiversity with American chestnuts, hoping to develop not only a blight-resistant tree, but also one that does not succumb to root rot, a malady more common in the South.

The chestnut blight was a devastating effect of globalization, but isn’t an isolated incident. Goodridge points to Dutch elm disease and the hemlock woolly adelgid as other examples of foreign pests and diseases that affect our forests in a big way. “We’re not just trying to save some old tree. This research could help prevent occurrences like this in the future.”

The prospect of American chestnuts stretching for miles again is an exciting one, but the only people likely to enjoy that view are the generations to come. If you want to view old-growth American chestnuts, there are some surviving specimens.

Perhaps the best way to commemorate the tragic tale of the American chestnut, however, is to appreciate the diverse species of trees that still cover this country: maples, oaks, tulips, and pines. You can start by planting one today.