I Am the Tooth Fairy

“I know you’re the tooth fairy.” Noah, my 8-year-old, looks me dead in the eye. We are out to dinner. A large television hangs from the wall. Without blinking, he looks back up at the screen. A small, dry wing falls from my back and lands on the floor like a candy wrapper. The thing about not existing is that sometimes it’s a lot like being a mother.

“Sorry, Mama,” says Eli, my 6-year-old. He pats my hand and takes a bite of broccoli.

I think about all the elaborate notes in pink cursive, the 100 hundred shiny pennies in a cloth pouch, the blue stuffed cat, the five-dollar bill, the Superman, the glitter trails, the wooden hearts, the breath I held, the way I ever so gently lifted the pillow, the sparkle-stamped envelope with the tooth fairy’s address: 12345 Tooth Fairy Lane, Moutharctica, Earth. I kept myself secret. I tiptoed. I used my imagination, and now I’ve been caught. Noah looks at me again with a mix of sadness and pity and suspicion. I turn around to see what he’s watching. It’s a cartoon about a sea sponge who lives with his meowing pet snail.

A little light goes out inside me. But I can’t locate exactly what it ever lit up.

After Tinker Bell drinks the poison Hook left for Peter Pan, and her wings can barely carry her, and her light starts fading, and after she lets Peter Pan’s tears run over her finger, she realizes “she can get well again if children believed in fairies.” “Clap your hands; don’t let Tink die,” says Peter Pan. Many children clapped, some didn’t, “a few little beasts hissed.” Tink, of course, is saved. She flashes “more merry and impudent than ever.” It doesn’t even occur to her to thank the children who believed. Tink, whose name sounds like a penny tossed in a glass. Tink, whose name sounds like a wish that won’t come true.

Often as a mother I am in a cold sweat juggling whimsy and delight. “Magic anyone? Endless fun? Astounding joy?”

“No,” say my sons, “we’re good.” And they are. It’s me who isn’t good. It’s me who wants it. And I don’t even want it.

Often as a mother I am in a cold sweat juggling whimsy and delight. “Magic anyone? Endless fun? Astounding joy?”

What I want is my sons’ illegible, lyrical teeth. I want to turn them into an alphabet just for us. Letters with crowns and necks and roots. Milk letters. Deciduous letters. In this language I would draw a map that clearly marks where my sons’ wonder is buried so they always know where to go on their coldest days.

Clap your hands; don’t let mother die. My sons clap their hands and I brighten.

I’ve never seen a fairy. I’ve never looked up and seen a faint green glow. The closest I’ve ever come was once as a child — in a dream — I ran after myself, and when I caught up to me and turned around I wasn’t there.

We take shelter in children to escape oblivion. We ask the child to drag around the unwieldy weight of magic. To clap wildly. To believe in what we believe in no longer. We ask the child to keep the awe we forgot how to hold. The fairy isn’t the fairy. It’s the child who is the fairy. It’s the child who is enchanted, a metaphor, a shape-shifter. My sons keep bursting out of their skin. They smell like poppies, warm earth, milk. And then one day, out of nowhere, they won’t anymore. They are losing their baby teeth at what seems an alarming rate. Adult teeth bloom in their mouths. Their limbs grow longer and longer like shadows.

For whom is a child’s childhood? I think it’s for all of us. But it’s not for when we are children. Our childhoods are for later.

Some believe fairies are the discarded gods of the oldest faiths. Like shed skins of light. They continue to exist because they believe, like a child, that they exist.

The fairy isn’t the fairy. The mother is the fairy. The fairy flits back and forth, uncatchable. Who is she? The fairy is the space between knowing and not knowing. It’s the realization as it dawns. It’s what glows between a mother and her child. It’s Puck sweeping the dust with a broom behind the door. The fairy is the dust. The fairy is the door.

In 1691, Robert Kirk, a minister in the Church of Scotland, wrote a treatise claiming fairies were as real as you or me. It wasn’t published, though, until 1851, when “The Secret Commonwealth” was printed in a limited edition of a hundred copies. We each, he wrote, have a fairy counterpart, a co-walker, an echo. He described fairies as “somewhat of the nature of a condensed cloud and best seen in twilight.” Their bodies are spongeous and thin. “They are sometimes heard to bake bread.” “They speak but little and that by way of whistling — clear, not rough.” “They hang between the nature of God, and the nature of man.” Their body is “as a sigh is.”

They do not curse, but among their common faults are “Envy, Spite, Hypocrisy, lying, and dissimulatione.” They are prone to sadness because of their pendulous state. They can cure a sick cow. They steal milk, and when they are very angry they spoil it.

On May 14, 1692, Reverend Kirk took a walk in his nightgown on the fairy hill beside the manse. Later that evening, on the same hill, his body was found dead. The body that was buried, according to locals, was a changeling. The fairies had kidnapped the minister in his nightgown, replaced him with a dead fairy, and held the reverend captive in Fairyland.

The punishment, it seems, for believing too much in fairies is to be snatched away by them for eternity.

Three days after I give birth to Noah, I am nursing him in a soft, beige rocking chair when a goat walks in. “Hello,” I say. The goat, being a goat, says nothing. Most likely, I am hallucinating from no sleep. Most likely, a little piece of this world has torn and through the rip a goat has walked in. The goat lays his soft head on Noah’s head, like a kiss. The room fills up with wildflowers and then empties of wildflowers and then the goat is gone. Who am I to say there is no thin veil between this world and fairyland? I know this now, but I didn’t know it then: I am the tooth fairy.

This is how you can tell if your baby has been replaced by a changeling: boil water in an eggshell. If your baby is a changeling it will laugh and reveal it’s as old as the forest. In all its years, it will say when it suddenly begins to speak, it has never seen anyone boil water in an eggshell. If you wish to keep the fairies away, put the Bible, a piece of bread, or iron in your child’s bed. And if you wish to see a fairy, take the rope that once bound a corpse to a bier and tie it around your waist. Bend over and look between your legs. A procession of fairies will appear. If the wind changes directions while you do this, it is possible you will drop down dead.

There are two kinds of fairies. There are the “trooping” fairies, who live together on a hill. And then there are the ones who attach themselves to individuals, like a haunt. If I were a fairy, I’m certain I’d be the second kind, but to tell you the truth I’d make a terrible fairy. A terrible mother fairy who writes about fairies, and by doing so angers them all.

We are at the pediatric dentist because Eli has flown off his scooter and landed on his face. The dentist, who looks more like a very old child dressed up as a dentist than an actual dentist, puts Eli in a chair and raises it with a crank to the ceiling. She climbs up a ladder and examines him in the air. “You okay?” I call out from down here. From all the way down here. She tells me his two front teeth will have to be pulled. “Bad news,” she says, smiling. She lowers Eli and climbs back down. She hands me a brochure on sedation options. She is wearing tiny pink sneakers. I imagine a back room filled with sparkling white teeth. Nightly she grinds them. And stirs the powder into her warm milk. Unlike the rest of us, she will live forever.

“Can we err on the side of nature?” I ask. “I don’t recommend that,” says the dentist who clearly was once a fairy.

She shows me two fake front baby teeth attached to a wire. After she pulls Eli’s teeth she can “cement the device into his mouth,” she says. “I made one for my daughter,” she says, her red cheeks glowing.

The dentist’s office is decorated like an amusement park: vending machines filled with toys, televisions frantic with cartoons, posters of wide-eyed animals in pants. The instruments on the dentist’s tray — forceps, mouth mirror, periodontal probe — shine as the only reminder of where we are. There is even a giant stuffed panda. All you need to do is leave your name and number on a small piece of paper for the chance to win. I am so distraught I almost enter. Would she deliver the panda herself? Would she knock on our door with the prize and then devour us?

“Let’s get out of here,” I say to Eli. “Let’s run, Mama,” says Eli. And we run. We run home where it’s safe. Eli’s baby teeth stay in for another year. And when they fall out naturally I add them to the rest. Between Noah and Eli I have twelve. Twelve teeth. Sometimes I just hold them. Noah’s in one hand. Eli’s in the other. Proof of their babyhood. Proof of the mouths they left behind. Those baby mouths that spoke words thickly accented by the land they came from. Maybe it’s those teeth that are the fairies. The ones the children, in order to grow, must cast off. The teeth that made little holes in the air with new breath.

If I were really the tooth fairy, I’d lay each tooth, like a body, on a rose leaf. I’d carry them one by one over my head through the streets. The air would brighten, and grow sad and sweet. And I would sing, though I cannot sing, a lament for everything I must remember and everything my sons must forget.

Last night I slept with all my sons’ teeth underneath my pillow. And when I woke up, Noah and Eli were leaving me notes. They each had a long white beard, and they were very old and wise and radiant. I had caught them. And then I woke up again.

First published in The Paris Review Daily.

This article is featured in the November/December 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Take the Fair Face of Woman, and Gently Suspending, with Butterflies, Flowers, and Jewels Attending, thus Your Fairy is Made of Most Beautiful Things by Sophie Gengembre Anderson (1869)

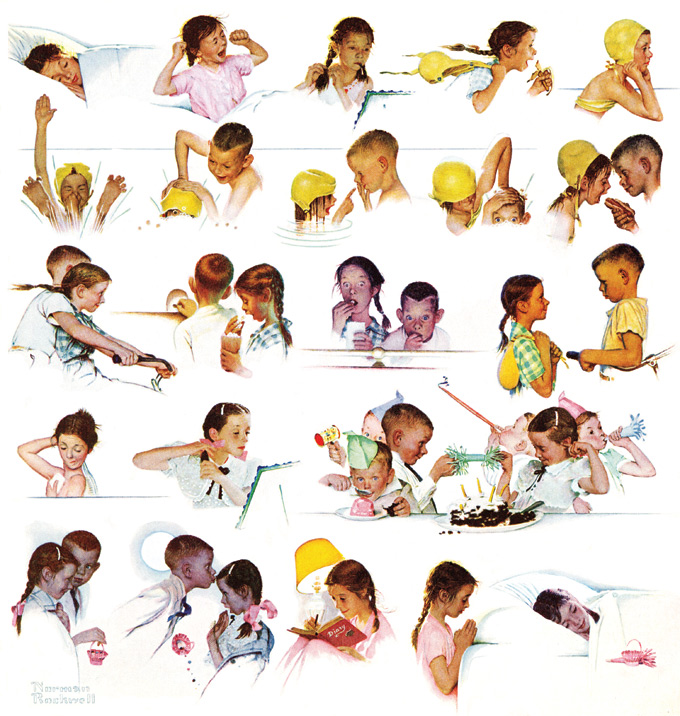

The Rockwell Files: Love at First Fight

Three months after Rockwell’s Day in the Life of a Boy appeared on the cover of the Post, he decided to document a day in a little girl’s life, too. He chose his favorite child model, Mary Whalen, to pose for the 22 images of Day in the Life of a Girl for the August 30, 1952, cover.

Rockwell had to be imaginative in posing Mary for the photographs he would use to inform the painting. To give the impression of her racing off to the pool, her mother helped by holding her pigtails back while someone else pulled on her swim cap. To simulate the mutual dunkings of Mary and co-model Chuck Marsh, Rockwell used a bronze bust. The kids posed as if to dunk the bust’s head under water so Rockwell could get their elbow angles correct.

Making Mary’s hair look soaking wet was easier: “They poured a bowl of water on me,” she said.

Now came the toughest challenge. Though the models got along when posing, Chuck absolutely refused to kiss a girl — no way, no how. He finally agreed to a compromise: Rockwell brought out the bronze bust again and photographed Chuck kissing it.

The finished cover resembled Day in the Life of a Boy except for one image. Rockwell had been criticized for not showing the boy saying his prayers before going to bed. So he removed one of the images in the sequence — Mary and Chuck thanking the birthday girl for inviting them to her party — to make room for Mary kneeling at her bedside.