Considering History: The Chinese Exclusion Act and the Origins of “Illegal” Immigration

This column by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

On Tuesday, May 29, at 8 p.m., PBS’s American Experience series will air the debut of an important new documentary film, “The Chinese Exclusion Act.” Created by award-winning filmmakers Ric Burns and Li-Shin Yu, narrated by actor Hoon Lee, and featuring contributions from numerous scholars, writers, and public figures, the documentary both dives deep into the 1882 law’s specific details and relates them to a number of longstanding American debates. I’ve had the chance to watch a screener of the film, and it features unforgettable primary sources and voices, reminds us of the most challenging and most inspiring sides to our shared histories, and powerfully reframes American identity and community through the lens of this too-often overlooked moment.

As I argue in my book The Chinese Exclusion Act: What It Can Teach Us about America (2013), the Act and its contexts helps us understand a number of issues with more depth. But perhaps none are more striking than the histories of American immigration laws, and how and why the category of “illegal” immigration came to be created.

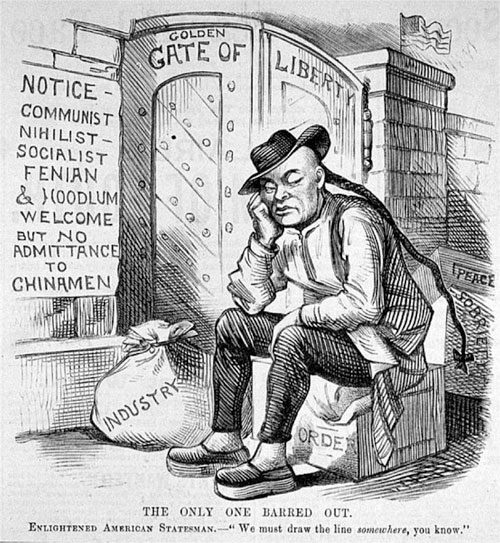

At first, America had no national immigration laws, and immigrant arrivals were subject to no legal categorizations. Then came the 1875 Page Act and the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act. These earliest immigration laws were designed to affect only very particular categories of arrivals, and in overtly and purposefully discriminatory ways: the Page Act defined Chinese female immigrants as likely prostitutes and excluded them on that basis; while the Chinese Exclusion Act went much further still, seeking to exclude virtually all Chinese arrivals.

These first immigration laws were the first to create the category of “illegal” immigration explicitly based on bigotry and xenophobia. As a result, all Chinese immigrants were affected by the law, just as all non-Chinese immigrants (virtually all immigrants until the 1920s Quota Acts) remained unaffected and did not have to worry about following any law. As of 1882, and for more than half a century afterward, if a Chinese person wanted to come to the United States, he or she would almost certainly have to violate these laws (a civil, not criminal, violation, as is the case with many undocumented immigrants).

As I traced in my first Saturday Evening Post article, the Chinese Exclusion Act and its many follow up laws—and thus the category of “illegal” immigration itself—were designed not only to limit future arrivals, but also to separate and destroy existing Chinese American families and communities. Stripping citizenship from those who had been able to attain it, making it illegal for Chinese Americans to leave the country and return, forcing Chinese Americans to carry a “resident permit” at all times or risk deportation—these and other provisions affected not future arrivals but present Chinese Americans, defining them as potentially (if not inevitably) “illegal” as well. A 1901 editorial in The Saturday Evening Post by San Francisco’s mayor reveals the depths of anti-Chinese bigotry in the era.

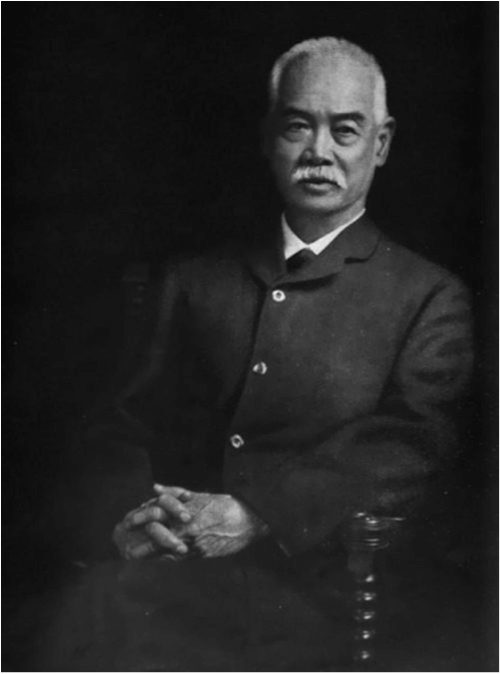

The case of Yung Wing, whom I also highlighted in that first piece, illustrates precisely how these legal provisions and categories affected Chinese Americans. Yung had been in the United States since his arrival in 1848 (at the age of 20), was naturalized as an American citizen in 1852 and graduated from Yale in 1854 (making him the first Chinese American college graduate), volunteered for the Union Army during the Civil War, married and had two sons with Mary Kellogg (an American-born resident of Connecticut) in the 1870s, began his long-planned Chinese Educational Mission in Hartford in the same decade, and by the exclusion era was part of American society and communities in every meaningful sense.

Yet that era’s exclusionary laws affected and severed every one of these connections. Yung’s citizenship was permanently stripped and his school was closed and its students forced to return to China. When Yung traveled to China on official diplomatic business, he was unable to return to the United States legally, a situation that contributed to his wife’s declining health and death and led directly to a long-term separation from his sons. Each of those events was entirely legal, and when he received a temporary diplomatic visa to attend his younger son’s 1902 Yale graduation — nearly half a century after his own such graduation and fifty years after he had attained citizenship — Yung risked becoming an “illegal” immigrant if he stayed in the U.S.

Yet I believe Yung did find a way to stay in the United States, with his sons, in his home and community, for at least portions of his final decade of life. His April 21, 1912 New York Times obituary, submitted from Hartford, noted in its opening sentence that he “died at his home here,” a deceptively simple phrase that suggests such “illegal” residency in the U.S. After all, any time that Yung spent living in the United States in the aftermath of the Exclusion Act and its follow-up laws was in violation of a number of those legal provisions and categories.

If Yung did remain in the United States during that decade, it would make him one of the first prominent, overtly “illegal” immigrants, in the first era when such a status was possible at all. Applying such a status to an immigrant and American with the multi-decade, inspiring story like Yung’s might seem inaccurate. But the opposite is the case: the category of “illegal” immigrant was created quite purposefully and specifically to apply to people like Yung Wing, and the communities to which he belonged. That’s one of many vital histories that the Chinese Exclusion Act, and the wonderful upcoming PBS documentary of the same name, helps us better remember.