Our First Christmas Without Mom

My mother died this past summer, so we’re sailing into the holidays absent our commodore. For the 63 years my parents were married, my mother let my father think he was in charge, though we all knew she steered the ship of state, both deftly and demurely.

It’s an odd feeling to imagine Christmas without Mom. She did much of the holiday’s obvious work, plus a hundred other little things we’ll likely forget in the holiday rush. I fear no one will remember to buy a flannel shirt for a down-on-his-luck man in our town, and have it gift-wrapped and under the tree, awaiting his arrival on Christmas Eve. He’s spent Christmas Eve with our family for nearly 40 years, and I don’t want the ball to drop on my watch, so I’ve written in the December 12 square of our refrigerator calendar, “Buy Dale a shirt.” Mom would never forgive us if Dale had to go without a new shirt this Christmas.

When I was little, maybe five or six, my mother took me to Danner’s five-and-dime on the Danville town square and bought me a little red Christmas elf to go on the tree. A few years later, the elf fell forward onto a hot bulb and rested there, burning his face. Now he’s an elf with a bad sunburn. Even though it was mine, Mom wouldn’t let me take the elf with me when I moved from home, but last year, while taking down the tree, she handed me the elf and told me to take good care of him. I’ve since invested that handing-over with all sorts of meaning — that Mom sensed it would be her last Christmas with us and wanted to make sure the elf was not orphaned. I keep it on the bookshelf next to my desk, its red face shining forth, keeping watch by night.

Mom never wanted anything for Christmas.

“I have everything I need,” she would tell us when we asked her what she wanted. So our gifts to her were always stabs in the dark, wild guesses, graciously received, but seldom used. Crystal vases, pottery, Irish sweaters, tucked away in back closets, while the handmade gifts we gave her as children — plastic birds, woven potholders, paint-by-number pictures — enjoyed an eternal place of prominence. One Christmas, after receiving a royalty check, I bought her a new kitchen stove and she spent the next year trying to pay me for it, slipping money in my pockets when I came to visit.

When I was a kid, I would tell my mother I loved her in the way small children do, spontaneously with great enthusiasm. When I became a teenager, and prone to embarrassment, I ended that practice and didn’t resume it for several decades. Even then, almost up until she passed, I would say it in a silly voice I reserve for endearments, so as not to sound too earnest. The day before she died, Mom took my hand and said, “I love you, Philip. You’ve been a wonderful son.” And for the first time since childhood, I told her I loved her in a normal voice. I wish I hadn’t stopped telling her I loved her when I was a teenager.

I’ve lived long enough to know Hallmark’s depiction of mothers isn’t entirely accurate. Having children doesn’t miraculously instill one with compassion, wisdom, patience, and love. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if one couldn’t sire or bear a child until those qualities were present? If God ever puts me in charge of reproduction, I’m going to do something about that.

But my mother had all those virtues and more, which I didn’t appreciate as a kid, so I would ask her for other presents at Christmastime, not realizing she had already given me the loveliest gifts one person can ever give another.

Philip Gulley is a Quaker pastor and the author of 22 books. See also our feature article about Gulley and his wife in the November/December 2017 issue.

North Country Girl: Chapter 2 — What I Didn’t Learn in Kindergarten

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

I had started kindergarten age four on the army base in Hawaii. My father, a captain, had wrangled this early admission to get me out of my mother’s hair while she coped with a new baby. After a several month gap in my education while we lived with my grandparents, I was sent off to Cobb Elementary School as soon as we moved into the Woodland house, in the middle of the school year. I was the new kid, the smallest kid, and a year younger than most of my classmates. The old maid teacher (the Duluth Board of Education required that all elementary teachers be grey or white haired spinsters) carefully instructed me that if I had to throw up I should not run around the room but stay in one place, the only useful thing I learned in kindergarten. I painted at the easel, sang Old McDonald, pressed my hand into a disc of wet clay to create a Mother’s Day present, and made not a single friend. This would have distressed my mother if she had had the time to notice; she spent the entire day wrestling with a skinny, shrieking, thrashing toddler who fought tooth and claw against sleeping and eating and everything else.

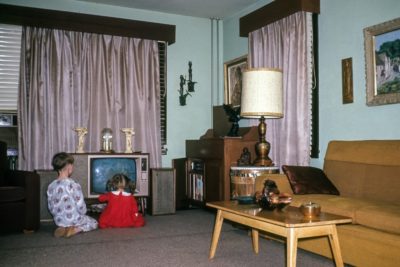

I was friendless, but not unhappy. I had my books and my dolls and a baby sister to boss around. And every day at 3, I had The Bozo Show on our black and white TV. When Bozo wasn’t showing cartoons, but clowning around in the studio, I went back to my book while Lani rampaged through the house. Neither of us were interested in Bozo’s puerile antics or the tedium of listening to the dozens of snotty-nosed kids squashed on bleachers trying to remember their own names for the camera.

At that time we only had two TV stations in Duluth, neither of which was particularly dedicated to children’s programs. On weekday mornings there was Romper Room, which my mother attempted to park my squirming sister in front of. I was a classic Goody Two Shoes and even I was repelled by Romper Room’s “Do Be a Do-Bee” kid propaganda. And I knew that at the end of each show when Miss Mary looked through her Magic Mirror, she would never see Gay and Lani, only Billy and Nancy and Susie.

The high point of my week was Saturday morning, the one time Lani and I could spend hours sprawled in all our glory and pajamas in front of the TV. The first thing to come on screen after the weirdly fascinating test pattern were wonderful old black and white cartoons, Merrie Melodies, Betty Boop, Popeye the Sailor Man, one after the other, with no interruptions from silly clowns or idiot children. Then came Mighty Mouse to save the day. The rest of the morning was not as idyllic, consisting of old half-hour shows thought suitable for kids: Roy Rogers, featuring Trigger and Dale Evans and for some reason Nellybelle the Jeep. The Lone Ranger and Zorro, both of whom were much handsomer and more dashing than stodgy Roy Rogers. Sky King, with his cute daughter, Penny, capturing various bad guys through aviation. And my favorites, the horse shows: Fury and My Friend Flicka.

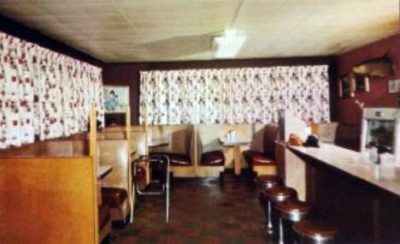

I had a few plastic toy horses, inspired by the far better collection owned by my one and only friend, Judy Lindberg, who lived a few houses down from my grandparents in Carlton. Judy and I had become friends during my parent’s house-hunting days, when she was summoned to play with me. Round-faced Judy seemed almost as friendless as I was. I envied her world-class plastic horse collection, her thousands of Legos (My mother hated anything with lots of tiny pieces), and her status as an only child, a rare exotic when two kids seemed the minimum and lots of families had five or six. Judy’s very German grandfather, Karl, and her parents, Vera, with raven Elizabeth Taylor hair, and roly-poly Julius, owned Carlton’s one and only restaurant. The small café had a few booths along one side and on the other a long counter with those glorious chrome stools; Judy and I were strictly forbidden to do any spinning on them. On the counter and tables were the most adorable china cow creamers, as Minnesotans drank coffee with every meal. I broke one once, mesmerized by the stream of milk pouring out of the cow’s mouth, and I was scared for weeks to go to Judy’s house, terrified of what Germanic punishment might be meted out by her formidable grandpa Karl.

I got to play with Judy quite often, even after our move to Duluth; my family spent almost every Sunday in Carlton. While the adults sat around drinking and talking and drinking, I walked myself down the street to Judy’s, where we played horsies or Legos or fooled around with her mother’s electric organ, or I would sneak a look at Judy’s collection of fascinating, brightly-illustrated books that tried to explain Catholic theology at an 8-year-old level. Judy complained that reading wasn’t playing, and she was right.

***

If Judy wasn’t around on our Sunday trips to Carlton, I roamed about outside by myself, or explored my grandparent’s big house. On the ground floor there was a small wood-paneled room decorated with the heads of animals. My grandfather loved to hunt; in the winter he would drive around the county, dropping bales of hay off in the woods to make sure enough deer would survive so he could shoot them the following fall. There was an elegant living room that we never sat in; everyone congregated in the new glass-walled sunroom my grandparents had added on so they could look out at the snow eight months a year. My grandmother had remodeled her kitchen at the same time; her aqua blue and pale yellow kitchen was right out of Disney’s Tomorrowland and seemed the height of modern sophistication to me: the freezer made ice, there was a dishwasher, and the Formica counters were festooned with space age parabolas.

Upstairs were “the boys’ rooms” that had belonged to my dad and his two brothers. There the main attractions were the leather albums of coins and stamps from Rhodesia, Ceylon, French Guinea, and other exotic-sounding places I longed to visit even though those countries were just a colorful bit of paper or a coin with a hole stamped out; I could not have found them on a map.

Also upstairs was my grandma’s big bedroom, neat as a pin, reeking of Youth Dew, and too intimidating for me to do anything besides look at myself in her three-sided dresser mirror.

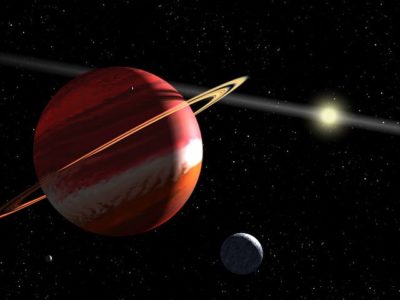

Best of all, my grandparents had a room just for books. It wasn’t big, but it was definitely a library, with towering bookcases on all sides holding hundreds of books in no particular order. There were tomes on dentistry, dusty fabric-covered novels with tiny type and no conversations, ancient nature books with pastel drawings of birds and moths—I just had to keep pulling books down from the shelves until I found something I could enjoy. When I did, I left that book on a lower shelf so I could find it again the following Sunday. There were two books I read again and again; a book on space travel, with lurid sci-fi paintings of the rings of Saturn as seen from the surface of that planet, and sunset on Mars with its two moons hanging in the sky; and a guide to hunting in Africa, bound in leopard-print paper and filled with black and white photos of living and just-shot gnus, zebras, lions, and a wide variety of antelope. If I ever go to Africa, I will carefully shake out my shoes every morning, having seen a photo of a large scorpion that had been extracted from the author’s boot. When I was in junior high, I discovered in my grandparents’ library an unaccountable paperback of Hell’s Angels by Hunter S. Thompson, with such horrifying descriptions of sex and violence, including bikers pulling a train on one poor girl, that I took special care in secreting it behind the encyclopedias so I could read it again and again. I have no idea who would have brought that book into that house.

My grandfather had a small bedroom tucked beneath the stairs, where he retreated immediately after Sunday dinner. I thought it was funny that my grandpa’s bedtime was 7:30 until I realized years later that this was his regular time to pass out from drinking 7&7’s all day. Every Sunday I scarfed down my own dinner as fast as possible to catch Lassie and the Walt Disney Show, which later became the even more unmissable Wonderful World of Color. My mother and grandmother cleaned up the dinner plates, my dad built himself a last highball, and then we piled back in the car, my dad drunk and all of us seat belt-less, to drive the half hour back home, where I had to go immediately to bed.

My grandfather’s brother was married to my grandmother’s sister, but while my grandpa was the big man and my grandma the snooty matron in their town of 400 souls, my great uncle Cliff and great aunt Marge were stuck on a farm with a thousand turkeys. Every Christmas Eve Cliff and Marge opened their rambling 1920’s house to dozens of relatives. Aunt Marge started baking in the beginning of December: there were cut-out sugar cookies shaped like stars, bells, and camels, dusted with red and green sugars; spritz cookies, ridged wreathes of pale green, decorated with those adorable little silver balls that you’re not suppose to eat, but that I could never resist crunching between my teeth; pfefferneuse, snowy with powdered sugar, that I always forgot I didn’t like until I had popped one in my mouth; chocolate drops, that I did like, tart lemon bars, homemade white bread to be slathered with butter, and stolen, studded with candied cherries and iced with white sugar frosting.

Marge made candy as well, a feat I have tried again and again to duplicate and consistently failed at: chocolate walnut fudge and penuche and divinity. These were the main attractions for me and it was torture to gaze upon the kitchen table groaning with sweets and not be able to have any until I choked down a plate of wild rice with mushrooms and chicken, baked ham, mashed potatoes, string bean casserole, and ambrosia salad. There were bowls of many other things, such as beets and lima beans, that I didn’t eat, and since it was Christmas, nobody made me. It was farmhouse cooking at its most gargantuan. I don’t think anyone even thought of bringing a dish to Aunt Marge’s Christmas Eve. It would have been like showing up at the miracle of the loaves and fishes with a Tupperware container of pasta salad. Our family did presents Christmas morning, after Santa came. Cliff and Marge did presents Christmas Eve, between bouts of eating. There was always one present for me, so I would have something to open; I tried not to look disappointed at the handmade monkey sock puppet or yoyo doll. Then there was that annus horribilius when my sister got a Raggedy Ann doll, something I had always wanted; I gleefully torn open my own gift to reveal the dreaded stitched grin of Raggedy Andy. I cried all the way home.

A Brief, Human Moment in Wartime

By 1914, modern machinery enabled men to conduct non-stop, highly lethal warfare. The human side of war, which had never been very large or very human, was diminishing. Killing seemed to go on day and night in the trenches on a scale no army had seen before.

Then, on Christmas Eve, German and Allied soldiers on the Western Front made one of the last gestures of chivalry in a major war. Without permission from their officers — which they never could have obtained anyway — they laid down their guns for a day. Men came out of their trenches, shook hands, exchanged their rationed goods, gave each other haircuts, played soccer, and generally conducted themselves as if they were back in their villages on Christmas Day.

The military commands on both sides were horrified by this insubordination. They feared it would render their soldiers incapable of shooting the men with whom they’d celebrated the peaceful holiday.

But the truce didn’t outlast the holiday. They shooting began shortly afterward.

When Christmas returned in 1915, 1916, and 1917, soldiers on either side showed no interest in a truce; they didn’t want to prolong the war a single day more by a ceasefire.

To honor the 100th anniversary of this extraordinary moment of peace in wartime, Audible Studios has produced Christmas Eve 1914, a full-cast dramatization following one company of British officers as they rotate forward to spend their Christmas on the front lines, written by Emmy Award winner Charles Olivier:

The entire program Christmas Eve 1914 is free for a limited time at audible.com/1914.

Sainsbury’s, An English grocery store, has also created the following commercial dramatizing events of the Christmas truce that has received more than 15 million views so far.