A Brief History of the NSA: From 1917 to 2014

As you might expect from an intelligence organization, the National Security Agency has always done its best to avoid unwanted scrutiny from the American public.

So naturally, the NSA was more than a little “uncomfortable” when Edward Snowden exposed its most secret intelligence-gathering programs, including spying on allied government communications.

But the agency isn’t a stranger to intelligence leakers, and it isn’t really news that the NSA has been spying on people here in our own country. As a matter of fact, that’s precisely their job, and has been since President Harry Truman ordered the NSA into existence in 1952.

The Black Chamber

The agency’s origins date back to July 1917, when a man named Herbert O. Yardley became the head of the newly created Cipher Bureau of Military Intelligence.

Just three months before, the United States had declared war on Germany and its allies. The need for better communications intelligence couldn’t have been more plain. One of the major factors that brought the U.S. into the war was the infamous Zimmerman Telegram, in which the German Foreign Secretary attempted to entice Mexico into war against the U.S. When British codebreakers intercepted this message, it naturally inflamed the U.S. and proved the value of signals intelligence.

After the war ended in 1919, Yardley’s Cipher Bureau moved to New York City and shifted its focus from military to diplomatic intelligence. Its greatest success came in 1922, when its surveillance of Japanese communications helped American diplomats negotiate with Japan at the Washington Naval Conference on naval arms limitations.

The Cipher Bureau’s methods were somewhat questionable: deals with Western Union and other telegraph companies gave the Cipher Bureau unprecedented access to messages entering and exiting the United States. When Secretary of State Henry Stimson decided to close the agency in 1929, he cited moral opposition to its increasing surveillance, though his reasoning may also have been partly financial. In any case, Hoover’s administration did not see the need for peacetime surveillance and the agency was shuttered.

Between World Wars

The end of the Cipher Bureau left Yardley unemployed and bitter. In 1931 he published The American Black Chamber, detailing the activities and exploits of the Cipher Bureau. The book, excerpted in The Saturday Evening Post, shocked the public and the intelligence community, as well as the countries Yardley had spied on. And so the founding father of American surveillance also became its first traitor. The National Surveillance Agency prophetically made the Edward Snowden comparison itself in a 1986 memo: It was as if an NSA employee had publicly revealed the complete communications intelligence operations of the Agency for the past twelve years.

By the time Yardley had published his book, it was already out of date on American spy programs. In May 1929, five months before the end of the Cipher Bureau, the U.S. Army had decided to form its own agency independent of the State Department. The following year, William Friedman began building the Signal Intelligence Service (SIS). It’s unclear to what extent the end of the Cipher Bureau and the birth of the SIS are related, but in October 1929, Friedman went to New York to obtain the files Yardley’s agency had gathered. The SIS expanded rapidly in the 1930s, especially in the Pacific, where it opened bases from Alaska to China to Australia in response to the increasingly aggressive Japanese Empire.

From World War to Cold War

The army’s decision to focus its surveillance on Japan proved prescient when a Japanese fleet attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. By then the SIS had already cracked Japan’s Purple cipher, used for diplomatic correspondence, and in March 1942, the SIS cracked the JN-25 code, Japan’s primary naval code, which enabled the U.S. Navy to anticipate the Japanese attack on Midway in June 1942. In another key success, the SIS uncovered Admiral Yamamoto’s travel plans, the commander-in-chief of the Japanese Combined Fleet. The army scrambled a squadron of American fighters to successfully shoot down Yamamoto’s plane in April 1943.

Following the war, President Truman reorganized American signals intelligence under the National Security Agency (NSA) in 1952. In 1957, the NSA moved to Fort Meade in Maryland, where it is still based today.

The NSA began as a secret organization, half-jokingly referred to by many as “No Such Agency.” But as the NSA grew to a peak of more than 90,000 employees in 1969–making it the largest intelligence organization in the U.S., if not the world–it became harder to deny its existence.

During this period, the NSA’s intelligence contributions helped the U.S. anticipate Cold War events like the Cuban Missile Crisis and the foundation of the Berlin Wall. But the NSA wasn’t always successful. Faulty intelligence in August 1964 distorted the events of the Gulf of Tonkin incident, drawing the U.S. into the Vietnam War.

In the Public Eye

The first wave of controversy surrounding the NSA came in the 1970s. The aftermath of Watergate brought U.S. intelligence agencies under suspicion, and alongside the CIA and the FBI, the NSA became a subject of the U.S. Senate Church Committee investigation in 1975. The committee’s findings exposed the NSA to public scrutiny for the first time.

The investigation brought surprising revelations. Since 1945, the NSA had been spying on telegrams entering and leaving the U.S., including the correspondence of American citizens, under a program called Project SHAMROCK. Under Project MINARET, the NSA monitored the communications of civil rights leaders and opponents of the Vietnam War, including targets such as Martin Luther King, Jr., Mohammed Ali, Jane Fonda, and two active U.S. Senators. The NSA had launched this program in 1967 to monitor suspected terrorists and drug traffickers, but successive presidents used it to track all manner of political dissidents.

The Church Committee’s findings led Congress to enact the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) in 1978, which set guidelines for what the NSA could collect and how they could collect it. No longer could the NSA conduct warrantless surveillance on American citizens; instead, the organization would have to go through a special surveillance court, created by the FISA act.

After 1978, the NSA returned to laying low, and with the end of the Cold War, the agency began to shrink into the early ’90s. Current estimates place the number of employees at around 40,000.

Terrorism, Data Mining and Edward Snowden

The NSA’s role shifted again following the September 11 terrorist attacks. In 2002, it launched a ‘data mining’ program to compile and sift through electronic transaction data. That same year, President George W. Bush authorized the NSA to monitor the phone calls and emails of American citizens without a warrant from the intelligence court. The New York Times exposed this program in 2005, and under legal doubts and public pressure, Bush ended the warrantless wiretap program in 2007.

In June 2013, the NSA returned to the media spotlight when NSA contractor Edward Snowden revealed that the agency had been secretly gathering Internet and telephone data on millions of Americans. Snowden also revealed that the U.S. was spying on allied leaders, such as German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

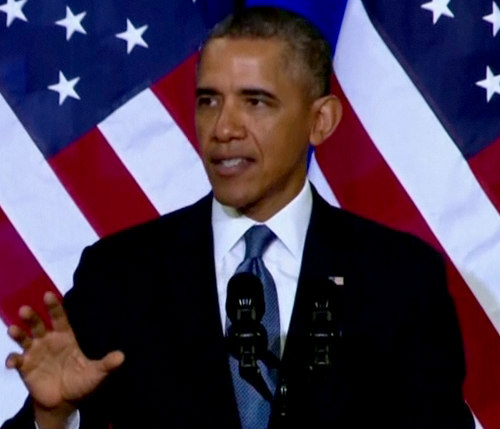

In light of the current controversy, the future of these programs is up in the air. In a speech given early Friday morning, President Obama announced that the NSA will no longer hold American phone records. It remains unclear whether phone companies or another third-party organization will manage this data.