Classic Art: Sporty Race Cars

by Frank Leon Smith

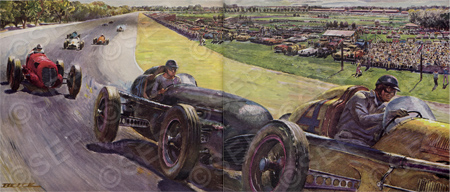

Illustration by Peter Helck

Click image to enlarge.

“Motors roaring around the track, skidding on the turns, battles for position, shouting crowds—could even these make the heart of the girl from Boston beat faster?” Frank Leon Smith asks in the 1946 story “Keep the Girl on the Fence.” We don’t know about the girl in the story, but it works during race season every year, in recognition of which, we bring you some midcentury illustrations of race cars.

Auto racing stories were popular in the Post in the ’40s and ’50s, and although the titles were sometimes melodramatic — “Murder Car,” “The Crowd Screamed” — a common denominator was the exciting illustrations by artist Peter Helck (1893-1988).

by William Campbell Gault

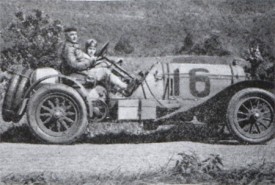

Illustration by Peter Helck

Click image to enlarge.

“The black job roared into second place, but its driver wasn’t trying to win. He wanted to kill the man ahead,” declares the intro to 1951’s “Murder Car” by William Campbell Gault. Although some of the fiction was overly theatrical, Helck was serious about the fast-paced scenes. He was also earnest about car racing, a passion honed as a young man when he witnessed the historic 1906 Vanderbilt Cup Race, featuring an American car built to beat the Europeans. Known as “Old 16,” the car won the Vanderbilt two years later in 1908.

from “Keeping Posted”

December 28, 1946

Click image to enlarge.

“Old 16 was built when the American automobile, then only a fast-growing youngster, first challenged the European builders,” wrote Post editors in 1946. “Motoring was just becoming something more than a fashionable—and pretty daring—sport. Two things were at stake: prestige and the booming American automobile market. Citizens of substance, if they had decided to trust their lives in one of these smelly new gas buggies, liked to buy European cars. There was a feeling that nothing built on this side of the water could equal such swank European cars.”

Helck acquired the legendary race car in the early ’40s. “Every time I take Old 16 out for a run, I recall the men who handled cars of that era—under the road and tire conditions they faced — and my admiration for their capabilities becomes a bit fanatic.”

by William Campbell Gault

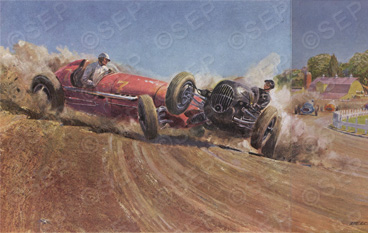

Illustration by Peter Helck

Click image to enlarge.

“It was the last lap of 100 miles of murder that he saw a car broadsiding in front of him,” the lead-in to this 1952 story declares, “ready to spill—and [here comes the title], ‘The Crowd Screamed.’” Melodrama aside, this is an all-but-live-action illustration.

Though Helck was best known for these fast-action scenes, he did a great deal of industrial commercial art as well. One testament to the variety of his illustrative skill is his work for Post sister publication, Country Gentleman, with scenes of a more bucolic nature.

[You can view Helck’s rustic scenes here, or visit Art.com to purchase.]

During his life, Helck described himself as an “auto addict” and wrote two books on racing—“The Checkered Flag” in 1961 and “Great Auto Races” in 1976—in addition to numerous magazine articles on the topic.

by A. Stanley Kramer

Illustration by Peter Helck

Click image to enlarge.

Learn more about the life and works of Peter Helck at Peter Helck, American Artist, a website maintained by the artist’s son and grandson.

The Politics of Rage

As the election season advances and campaign rhetoric gets more heated, candidates will be tempted to make more attention-grabbing statements.

The war on terror is sure to be part of the debate. We can expect candidates’ promises to be more ruthless in preventing terror attacks, while criticizing their opponent for being “weak” on extremists.

Already we’re hearing plans to match the radical Islamists’ barbarity, and attack our enemies, and suspected enemies, with a fury that has never been part of American policy.

History offers us a lesson in the politics of rage. Over the centuries we’ve seen that indulging hatred has consistently failed to achieve long-term success. During the Second World War, for example, when the U.S. was fighting two global powers, some Americans said we needed to hate more to achieve victory.

In a 1943 editorial, the Post editors had an interesting response to this call for hatred. They praised the Americans’ indifference to “the recent effort of a small group of super-duper-patriots to make the rest of us feel guilty for not hating the enemy enough. More hate, it was urged, was needed if we were to win the war.” Hating more, the editors continued, would probably not help America win the war any sooner.

In fact, hating might send the country off in the wrong direction, according Staff Sergeant Hobert Skidmore. Stationed on the war’s front lines, on “a far-away island in the Pacific,” he believed America couldn’t afford the luxury of hatred or vengeful violence.

In his Post article, “We Don’t Need to Hate,” he agreed that anger had its uses. It gave soldiers in combat the courage and strength they needed to achieve the nearly impossible. “But it must be controlled. An angry man has his guard down. He endangers himself and the other members of his ship, or plane, or gun crew or foxhole. There is a word we have in the Army for a guy who is always filled with anger and hatred. It isn’t a pretty word.”

American anger would have been at an all-time high when Skidmore’s article was published. The Japanese had just begun launching kamikaze attacks, pilots flying their explosive-laden aircraft into U.S. war vessels.

But Skidmore cautioned Americans against giving in to hatred: Blind fury was the sign of desperation and impending defeat. And once a nation gave in to savagery, it lost its self-respect, along with its respect for other nations.

|

|

|