End Clutter Now!

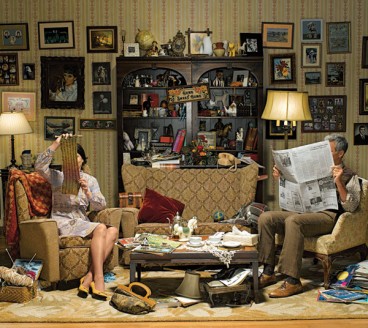

Some people wear their emotions on their sleeve. Others manifest it in the nest: The state of their homes reflects their state of mind. When depression sets in, the clutter can pile up.

Charles Miles can relate. He owns a three-bedroom Colonial-style home in Bogota, New Jersey, but when he’s feeling blue, routine maintenance is hard to keep up. “There are dishes in the sink. Newspapers on the floor. Instead of putting things away, I leave them where they are. I think, ‘What’s the point?’ I’m just not motivated. It’s the demon I fight all the time.”

Healthcare professionals know all too well the connection between clutter and depression. The abilities you need to keep a home clean and in relative order go by the wayside with depression. People who lose their drive find it hard to handle basic housekeeping and organizational tasks. “A systematic pattern of home neglect is really a form of self-neglect,” says Dr. Holly Parker, a practicing psychologist and faculty member of Harvard University. “People with depression often have low energy, almost like taking gas out of the tank of a car. They lose the motivation to do things they used to love to do. If they give up hobbies, they definitely won’t do housework.”

Clutter is difficult to contain under the best of circumstances. Every Felix Unger has a bit of Oscar Madison in him. For most, it’s a matter of having too much stuff and not enough places to store it. Some have called it an epidemic of affluenza. As a nation of affluence, we buy without thinking what we’re going to do with it, how we’re going to use it, and where we’re going to put it. And because we’re busier than ever, we have less time to figure it all out.

The fact is that previous generations simply didn’t have all the stuff we have today. They were never tempted by 24-hour shopping channels, blasted with emails about last-chance sales, or bombarded with catalogs and junk mail. Generations from baby boomers to millennials may have it all within reach, but most haven’t learned how to keep it in balance. Homes continue to grow fuller, despite our households growing smaller.

It’s not the whole problem, though. Clutter isn’t just about bringing new stuff into the home but the inability to purge the old. Some adhere to the waste not, want not school of housekeeping. Obsolete electronics? Clothes that haven’t fit in years? Broken tools? Folks with a Depression-era mindset hate to throw anything away. And then there are the objects with sentimental value, the biggest clutter culprits because they’re the hardest to part with of all. It’s little wonder why in the U.S. alone, the self-storage industry is a $22 billion business annually.

Living in clutter is more than just a matter of aesthetics. Clutter is an energy sapper that takes its emotional toll and steals domestic joy. If home is where the heap is, it’s a good bet family members are more stressed and less productive. It can create tension in personal relationships. It can cause people to be chronically behind schedule because they can’t find their car keys or they’re unable to sift through their closets for a complete outfit in the morning. And children can suffer as well. Some youngsters experience problems at school because they’re routinely late for class or under prepared for assignments.

Clutter comes in degrees, from mild to severe, from annoying to debilitating. While it can cause anxiety and depression, it can conversely be a symptom of a problem. Professional organizer MaryJo Monroe, owner of reSPACEd, a residential organization and design firm in Portland, Oregon, says one of the first things she notices working with a client who might be depressed is low energy output. “They don’t have stamina. Instead of working two to four hours at a stretch, they’ll start to poop out after an hour.” Another red flag is difficulty making decisions. When the ability to concentrate wanes, figuring out whether to keep, toss, or relocate things becomes impossible.

Self-esteem issues can be at the root. The attitude? I’m just not worth the effort. And it spirals downward from there. When it becomes hard to muster the motivation to turn things around, it can create a negative cycle that feeds on itself. People often become more stressed and more depressed because of the mess. And the inability to dig oneself out brings on feelings of hopelessness.

Losing his job of 14 years started a downward spiral for “John” who was living outside Seattle, Washington. He defaulted on his mortgage and lost his home. The stress caused the dissolution of his marriage and alcohol took over his life. “I started letting things go. Dishes piled up in the sink, garbage was almost never taken out. After all, what was the use? I knew I could pull myself out of it. But not today. Today I didn’t feel like it. I felt like sleeping.” Through the help of a friend, John went into a detox program and got help for his depression. He moved to a new state, got a new job and apartment. “As for how I feel when I come home, the difference is amazing. Coming home to a neat place, and knowing that everything in it—including the cleanliness—was earned by me, makes everything I do there, from waking up in the morning to watching the Late Show before I go to bed, that much sweeter.”

And that message of hope is exactly the one professionals strive to communicate.

Spring is an ideal time to start getting clutter under control. For many, seasons can have a powerful affect on their moods. In the spring, the days are longer, flowers start blooming, people are out and about. Those who struggle during the short, dark days of winter perk up in the spring. “It’s an uplifting time,” Parker says. “You can capitalize on that time of year by getting more things done and capitalize on that boost of mood that comes with longer days.”

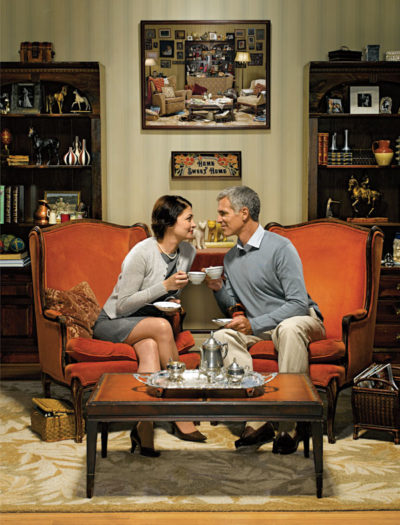

Solving clutter problems is a two-step process that takes planning. The first part is getting to the root of the problem, and a number of treatments can help such as therapy, medication, and doing regular exercise.

The second part is putting a system in place. (See “Seven Steps to Clutter Control.”) Enlisting a friend or family member in the organizational process can give the chronically disorganized the cheerleading morale they need to keep going. A home that looks good helps us feel good. And New Jersey homeowner Charles Miles can relate to that, too. When his outlook brightens, tackling the clutter is job number one. His reward for a home organizational makeover is a sense of accomplishment and renewed self-confidence. “I feel great,” says Miles. “I’m like, ‘Let’s invite the neighbors over for dinner!’”

Illustration by Gwenda Kaczor.

Conquer Clutter

For some time the least-used part of our house, the basement, had been the cause of the most stress. Strewn about and packed into the sectioned spaces—a finished playroom with two storage rooms on either side with exposed cinderblock walls—were baby furniture and toys, car safety seats, obsolete electronics, boxes of books, cans of paint, camping and sports equipment, bags of jumble, and three boxes containing the entire written and photographic archives of a deceased wing of my mother’s family.

I was all for eBay and turning old stuff into cash, but neither my wife nor I could work up the enthusiasm to act on this idea. The cluttered space below the stairs where neither of us could bear to go slowly began to develop into a field of conflict. The two of us are of a single mind about many things—about most things—but we realized that we differ on stuff. It took us a while to realize this, but one day as we were struggling (okay, arguing) about the functionally cordoned off no-go zone down there, it hit me: I was a hoarder; she was a stockpiler.

There’s a fine distinction. As a hoarder, I can never let things go, sensing either sentimental or monetary value in items that are notable to my wife only because they occupy valuable space. I had boxes of postcards people sent me in the 1980s. I kept computer cables. (Hey, you never knew when they might come in handy.)

As a stockpiler, my wife is a member of a different species entirely. The stockpiler always buys more than he or she needs, then justifies it in economic terms. Buying in bulk saved my wife from having to make multiple trips to Costco and Trader Joe’s, she explained. I understand the argument perfectly when it comes to paper towels, toilet paper, and lightbulbs, but it didn’t explain what looked to me like a lifetime supply of chocolate sauce. The reason for that, she said dismissively as if I were missing the whole point, was that she bought more after forgetting she’d already stockpiled a goodly amount a few months earlier.

Consider the types, though. One is focused on what’s past, the other on the future. So we came to see the basement as being divided between my urgent desire for historical preservation and, well, her grand vision. Or to put it another way, between my junk and her supplies. (“Not my supplies,” she would say, “our supplies,” since I too would use the stocks, including, naturally, the chocolate sauce.)

We agreed we needed to address it, but because it was out of sight we just let it grow. To an outsider, it might have seemed as if we were nurturing an indoor junkyard.

Then I got into a conversation with Richard Lyntton, who had a business to help people deal with their clutter. Lyntton developed his thinking during five years of sharing space with fellow soldiers in the Royal Tank Regiment. “When you’re in such a confined space, it forces you to consider what you truly need,” he told me.

Lyntton sees clutter as more than a matter of just, well, matter. “Most people think of it purely on a physical level,” he said, “but clearing physical clutter is a good place to start clearing your whole mental and spiritual deck. What matters ultimately isn’t the thing itself but that you have a feeling of peace.”

As far as my historical preservation project was concerned, he suggested loading a rented truck and dropping it all at a local thrift store. “Just get rid of it,” he said. “It’s all dead energy. You’ll feel great once it’s gone.”

And so I determined to address the mess. Taking Lyntton’s advice not to procrastinate, I went to the basement without so much as a pit stop at the fridge.

I went down deep. Real deep.

There were photos, letters from an old girlfriend, schoolwork, and stories and diaries that I felt vaguely embarrassed to read now, as if I were sneaking a peak at someone else’s private life. Other objects, too, cued remembrance of things past, and the experience of poring through the stuff seemed to telescope events, making them appear closer than they had been in years. An old typewriter took me back to my first ambitious—if grandiose—days of writing, blazing away in the basement of my parents’ house.

The act of disposing became by turns emotional, sentimental, and then, finally, cathartic.

Lyntton was right that all the stuff wasn’t just stuff, but it wasn’t “dead” at all. It was a record. Events and relationships had run a course with a beginning, middle, and end. People had married, borne children, divorced, and died.

“If I knew things would no longer be,” says the narrator at the end of the Barry Levinson film Avalon, “I would have tried to remember better.”

I scored my vanity a few times, too, with photos that were like time-lapse shots for a PowerPoint presentation on aging. Which pushed me toward another thought: Where have all the years—my years—gone?

The fear of the future, the unknown, is common enough, but what spurred my fear of the future was how quickly the past had passed. Childhood passes under the pressure of anticipation, slowly while it’s in progress, but as a parent, at least for me, the years have seemed to float up and burst like bubbles. The past was contained in finite objects, and they reminded me of the finitude of time.

Of course, there’s a practical side to it all, too. If the objects help you remember and, so, give a certain shape to your life, they have a totally opposite impact on your digs. They accumulate, time stuffed into a space. A brave few pay $100 an hour to get walked and talked through the process of divesting. Some people are forced to deal with it at certain times, such as when they move or when the spirit moves them, but it’s inevitably left to the people who bury the dead to toss out their junk as well—and to wonder why the heck anyone would keep thus-and-such.

My afternoon of purging passed quickly. The garage filled with stuff that I vowed I would soon take away to the thrift shop or the dump. My wife came home. “Wow,” she said, “you really did some job. You look tired.”

“I feel all cleaned out,” I said.

She surveyed the basement, the cause if not the scene of a few battles. Enough space had been reclaimed that we could find a meeting place somewhere in the middle of the room to start armistice talks. She considered the open space.

“I’d say it looks like we’re about halfway there,” she said.

“I was just thinking the same thing.”

Spring Cleaning Magic

Three rules that will completely change the way you think about clutter—and make it easier for you to let stuff go!

Cleaning house is not just about clearing away the stuff, the experts say. It’s about clearing your mind. The less stuff you have, the more space you have to think. Whole books have been written about cleaning away clutter, but the following principles will save you hours of time (and much agony).

• The Six Month Rule: Start in your bedroom and take out every object and article of clothing, says Donna Smallin, author of nine books on eliminating household clutter. Then, one by one, pick up each thing and ask yourself if you’ve used it in the past six months. If you have, put it back. If not, put it in the discard pile. Advance to the next room. Repeat.

• The Irreplaceable Objects Rule: Some things—such as vital papers and photographs—can’t be thrown out. Consider scanning paperwork and photos and saving them on your computer. Of course, computers can add another significant layer of clutter. Both the Windows 7 and Apple Lion operating systems will save your files on an external hard drive, and various programs (such as Lucion Technologies’ FileCenter, $49/year, and Carbonite Home, $59/year) allow you to archive material in a way that you can store it safely and out of the way.

• The Re-sale Rule: What do you do with the stuff you’ve cleared? Richard Lyntton, our declutter expert, said that trying to make money from it is a mistake. It takes time and a level of commitment that takes you, once again, back to the past from which de-cluttering is meant to liberate you. You’ve already used what you’re getting rid of, so now it’s time to give it away and let that energy go. Pass it on to a local charity or, better still, someone you know who needs it.

Spruce Up Your Home in Minutes

Tactics for emergency cleaning on short notice.

Your friends and family would never just drop in without calling. Except, of course, when they do. Let’s say an old friend or one of your children has phoned that they “just happen” to be in the area—meaning they didn’t want to plan a lengthy get-together but now they want to drop in and be watered or fed.

No, they don’t just want to go to a restaurant. Slight problem: Your place is a mess. You were going to clean tomorrow, but there’s no time for that now. What do you do? Here are some quick-clean tips that will help get you out of a jam.

• Make a Point of Odor. Spray air freshener around. Not too much!

• Clear the Decks. Find an empty box or laundry bin—anything!—and start tossing in loose clothes, candy wrappers, damp bathroom towels, dirty dishes, and the like, writes Sarah Aguirre, on about.com. Fill it up and stick it in the back of the closet. Don’t try to clean the whole house. Just target the most important areas. Where are you going to be hanging out? Living room? Back porch? Hit up these areas and leave the rest.

• Wipe Clean. Spray a rag with a cleaning solution such as 409 or Fantastik if you have it handy (dish soap if you don’t). Wipe down kitchen surfaces first, then bathroom, and finally the dining room table.

• Freshen Up Your Self. Aguirre points out that your visitors are not coming to see your house, really, are they? They’re coming to see you. Look in the bathroom mirror. Brush your hair. Check your clothes. Women, freshen up your makeup; men, if you haven’t done so already, shave.

• Divert Attention. Use something colorful—a plant or a bouquet of flowers or string of Christmas lights—to distract your guests from the less-than-perfect state of your home, says Frayda Kafka, a hypnotherapist based in Lake Katrine, New York. “I throw a brightly colored dish towel over my dishes. Someone looks in my kitchen, they see the red thing and they don’t notice anything else.”

• Dim the Lights. Another way to distract, according to Kafka: Light some candles if you have any. Nothing hides imperfections better than low lighting.

• Finally, Don’t Apologize. “When you do that, you simply call attention to the imperfections that most people wouldn’t notice in the first place,” says Kafka. The house or apartment won’t look perfect, sure. But, this is a triage situation: You are simply striving to make it look presentable.

Curing the Clutter Epidemic

We live in a world of things, of junk, of stuff. This fact was brought home to me—literally—when I left my job after 17 years. I carted the contents of my office home in three garbage bags that sat around the house for the next six months. Every time I tried to sort through those bags and commit to getting rid of any of it, I became paralyzed by fear (Would I need this later? Would I miss that once it was gone?) and overwhelmed by the task at hand. And that was just three bags—most of it paper! How would I ever sort through all the other stuff cluttering up my home and my life?

It’s a question many Americans ask themselves every day. Thanks to an abundance of cheap goods, instant credit, and constant exposure to the persuasive powers of advertising, acquiring has in itself become a national pastime. And a national problem, as our closets, attics, and lives become overwhelmed in an epidemic of uncontrolled clutter.

“We’ve begun to buy and hold on to so many items that we’re now having to acquire more and more space to accommodate our clutter,” says Dr. David Kantra, a psychologist in Fairhope, Alabama who studies the clutter problem.

Birth of an Obsession

Paper Chase

One of the biggest sources of clutter in our lives is paper—bills, receipts, or the instruction manuals from all the stuff we’ve bought.

Here’s how to tame it:

• Gather supplies. You’ll need a recycling bin, garbage bags, file folders, a pen, and a shredder.

• Establish a sorting area. Set up a folding table or quadrant of the floor—you’ll need room to spread out.

• Ditch the obvious. Long-expired coupons or instructions for products you no longer have can lurk in a desk for years. Pitch ’em.

• Create four paper management systems for:

1. Action items—bills, timely paperwork

2. Essential paperwork not needed on a daily basis, such as bank or insurance statements

3. Vital records—birth certificates, Social Security information, various account numbers

4. Archives for tax returns, legal papers, and/or family memorabilia

• Maintain the system by scheduling time to file papers. Organization is an ongoing process.

The ready availability of merchandise of every stripe was something that didn’t exist throughout most of American history, but the problem of clutter traces its origins back further than you might think—all the way to the 19th century. The rise of industrialization and the mass production of products created a cult of desire that has survived the decades, through economic booms and busts, where accumulating goods was viewed as the road to happiness.

That idea became more pronounced in the 20th century, as the power of advertising linked products to a lifestyle. “The message became ‘you are what you own,’ ” says Dr. Lorrin Koran, professor emeritus of psychiatry at Stanford University Center. Retailers responded to that insatiable desire for ownership. Remember the general store? It used to stock about 1,000 items in three or four aisles with one lane for checkout: That was all we needed. Today, you could fit almost the entire contents of that old store into one aisle of a huge discount chain that sells everything from hamburger meat to motor oil to flat-screen TVs. The average super retail center carries more than 100,000 products in mega-stores that stretch the equivalent of nearly five football fields. Shopping malls have become veritable mini cities containing hundreds of stores, food courts, ice skating rinks, movie theaters, even hotels.

And there’s always the Internet. Last year, online shoppers spent $204 billion on merchandise: The auction site eBay alone reported sales of $59.7 billion on merchandise ranging from brand-new cars and homes to vintage collectibles and antiques.

Retailers aren’t the only ones who have catered to this acquisitional trend; the housing industry has, too. In the past 30 years, the size of the average American home has grown 53 percent, from 1,500 square feet to a little more than 2,300 square feet. That’s an extra 800 square feet for stuff. But instead of becoming more organized with this space, homeowners have filled it up, rather than outsource to storage facilities.

“We’re at a point where people don’t know how to make decisions about quantities of things and whether items serve a purpose,” says Laura Leist, president of the 4,200-member National Association of Professional Organizers and the voice of a service industry that has sprung up to help people clear the chaos from their homes. They aren’t the only ones: More than 20 states have chapters of Clutterers Anonymous for clutterers in crisis.

Back to Basics

I wasn’t ready for a 12-step program yet, but it was clear I needed some help. So I consulted a local professional organizer, who helped me sort through my junk and discard what no longer had value. One of the first rules many organizers instill in chronic clutterers is: make the time. Just as someone trying to lose weight needs to set aside time for exercise, someone trying to shed stuff needs to commit to at least 30 to 60 minutes a week sorting through closets, files, and storage areas. Mark the time on your calendar and treat it as a standing appointment.

I learned other tips to help whittle away the clutter in my house and control what I brought in so that new junk wasn’t replacing the old.

I’m still working on the rest of the house, but I eventually got rid of that stuff I’d brought home from the office. Now, the only garbage bags on my floor are the ones that are on their way to the trash.

Cash for Clutter

What better way to rid your home of excess stuff than turning it into cash? But before you advertise your yard or garage sale, you need a strategy that maximizes your profits and puts the biggest dent in your clutter, says Barry Izsak, a professional organizer and author of Organize Your Garage in No Time.

Here’s your checklist:

1: A few weeks before the sale, give everyone in your family a box to fill with items they no longer want or use. If you’re not sure what to toss, Izsak offers three ways to decide: “If you don’t love it; it’s not useful; and you haven’t used it in several years, turn it into cash,” he says.

2: Schedule your sale of a Saturday near the first or 15th of the month, when most people get paid.

3: Scrub, wash, or polish your stuff. Make sure toys or electronics have all the pieces attached. Hang clothes on a rack. Use plastic bags to group children’s puzzles or hold hardware nuts and bolts.

4: Put price tags on everything. “People don’t want to ask you how much stuff is,” says Izsak. For small items, create a nickel-and-dime box.

5: Display your wares on a table or a board between two saw horses. Don’t make people bend down to look at your stuff.

6: Have an extension cord handy to show that appliances and electrical gadgets work.

7: Be flexible when it comes to price. “If someone picks up something you’re selling, be willing to deal with them right then and drop your price,” says Izsak. “They may be the only person all day who wants that item.”

8: Get rid of what’s left. It’s already out of the house, so keep it that way. Put unsold stuff by the curb, or cart it off for donation as soon as your sale is over.