The Art of the Post: From the Pages of the Post to Museum Walls

Read all of art critic David Apatoff’s columns here.

The illustrations that appeared in The Saturday Evening Post were intended to last until the next issue came out. The Post was a “periodical,” designed only to fill a period of time until it was updated by a newer issue containing more current information, fashion trends, and merchandise for sale.

Generations of illustrators created beautiful pictures to fill the Post and other magazines, but it was always understood that they were creating temporary art; one day that thin magazine paper would turn brittle and yellow with age, and eventually crumble and return to mother nature.

It took a while for experts to recognize that illustrations had enduring value, but once Norman Rockwell’s 1951 cover for the Post, “Saying Grace,” sold for $46 million, even the most stubborn nay-sayers realized that this “temporary” art form was worth preserving.

Today illustration art is being rescued and conserved by experts, to take its rightful place on museum walls.

During the decades when Rockwell and other illustrators were exiled from “fine” art, thousands of drawings and paintings were saved from the trash heap by a hardy band of collectors and artists who had the courage to ignore the condescension of highbrow art critics. These collectors weren’t intimidated by labels. Instead, they collected for the best possible reason: they loved the images. Their love of the pure art made them fearless, and they helped preserve the art form in private collections while the experts slowly had a change of heart.

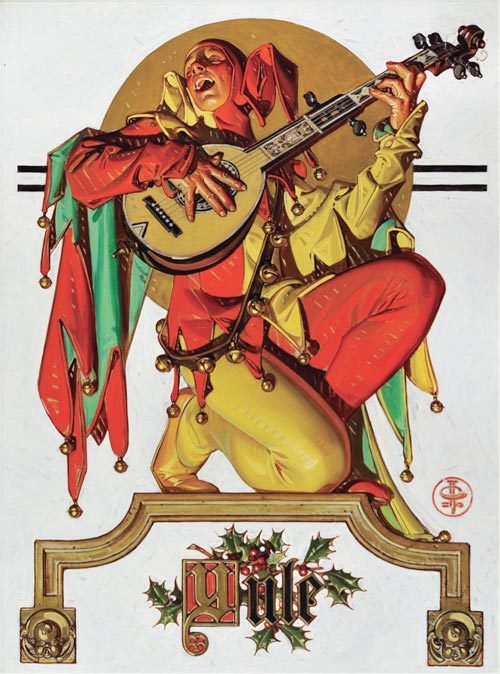

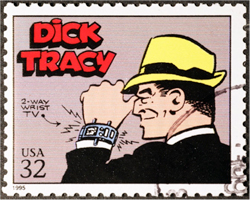

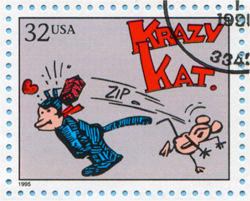

One such collector was Andrew Sordoni III, who started out as a young boy smitten by the art in Sunday comic strips. He liked Dick Tracy and Krazy Kat and a handful of other strips that were delivered to his house in the funny papers. Fortunately, Sordoni’s mother was a fashion illustrator, and she taught him to respect the craft of good drawing. For many years “craftsmanship” was a dirty word in the fine arts community, but it served as a polar star for Sordoni’s collecting. Soon Sordoni began collecting unfashionable illustrators such as Maxfield Parrish. Today Parrish paintings have sold for millions of dollars.

|

|

|

U.S. postage stamps featuring comics Dick Tracy and Krazy Kat. (Shutterstock) |

|

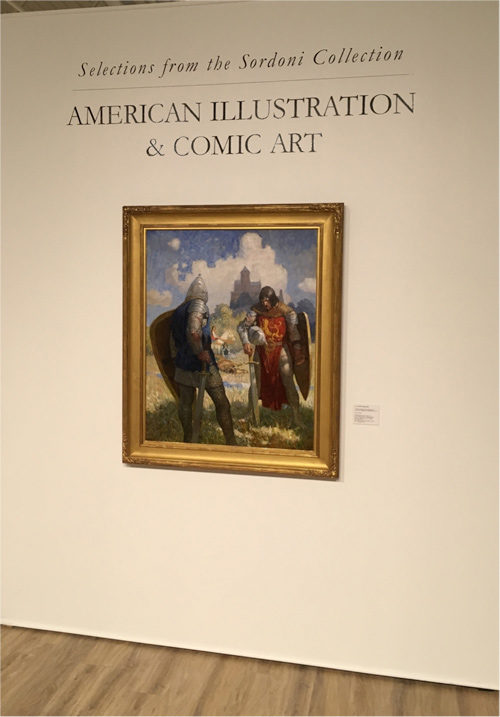

A lifetime of collecting has come to fruition in an opening this month of a large exhibition of American illustration art at the Sordoni Art Gallery in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania.

The show, which features one of the great private collections of American illustration, will run from April 7 to May 20, 2018. It was curated by Stanley I. Grand, Ph.D., a professor of art history and expert on the allegorical engravings from Giovanni Battista Ferrari’s De Florum Cultura.

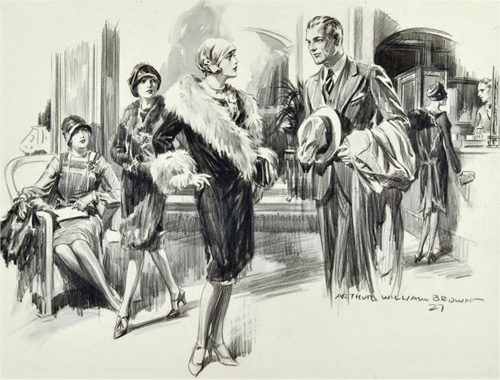

The Sordoni show includes 135 works of art, including a number of illustrations that were originally seen in the pages of the Post, but which now can be seen as the artist created them.

The collection reflects the personal taste of Sordoni, who collected what was once ignored as “lowbrow art.” As the catalog notes, “Andrew found his own way and collected works that were considered of lesser importance at the time, but are now highly regarded both in market and aesthetic terms.”

The art in the exhibit includes work by famed illustrators such as Rockwell, Parrish, and N.C. Wyeth. The substantial catalog accompanying the show is a prime example of how critical attention surrounding the field of illustration art has evolved from initial skepticism to serious study by respected academics and biographers who are devoting years and substantial critical analysis to multiple biographies.

While Rockwell was a groundbreaker in being accepted by the “fine” art community, other illustrators whose work appeared in the Post are hot on Rockwell’s heels. Artists such as J.C. Leyendecker, Dean Cornwell, Bernie Fuchs, Robert Fawcett, and others all have their own coffee table art books now, and the value of their original work at auction has increased dramatically. While illustration art was once auctioned in a separate category, much of it is now commingled and sold interchangeably with traditional American “fine” art.