How to Cook a Muskrat and Other Wild Dishes from 1938

Squirrel potpie? Old news according to 1938 Country Gentleman author Jim Emmett, who was on the hunt for more unusual home-cooked fare. Stuffed raccoon, parboiled porcupine, and opossum roasting over an open fire were just a few of his tasty finds. Plus, a tip for foraged edibles: Fried or drizzled, wild greens go down best with butter.

A note to the 21st-century chef: Take these dishes with a grain of salt. Food safety has changed some in the 80 years since these recipes were published. To know what’s safe to eat — and, more importantly, what isn’t — in your area, seek out local wildlife and foraging experts.

Savory Dishes from the Wild

Originally published in The Country Gentleman, March 1938

Your ancestors, or mine, may not have endured Plymouth winters, trekked Midwest plains, or even been born in this country; still, there is a good bit of the pioneer in the make-up of most Americans. A joint of venison sent to the house is eagerly enthused over, we cook precious wild ducks and upland game birds with fear in our hearts that they may be spoiled in the oven, and even prepare potpies of squirrel or rabbit more carefully than we do expensive cuts of meat.

The eating of only certain wild animals is a habit passed down from days not so far back when a farmer stepped outside his door to shoot a deer nibbling apples from the tree he cared for so carefully. Naturally, with game so plentiful nothing but the best graced his table. Fat bear and young deer not only butchered quickly but yielded a large supply of good meat at the expense of a single charge of expensive powder and precious ball. Canvasbacks and mallards were preferred when the waters of every inland pond blackened at dusk with southbound birds, and trout from the pasture brook which appeared on the breakfast table then would be entered in fish contests now.

This preference for certain wild game seems also to be a matter of location. For instance, in the North, muskrat haunches are considered a delicacy by most French-Canadian families, and in the South, opossum is enthused over on the plantation owner’s table. Frog legs are preferred to chicken drumsticks in the Adirondacks, while on many a Tidewater-Maryland farm eels are a greater favorite than the oysters, crabs, and fish lying off the wharf for the taking.

How to Pluck a Possum

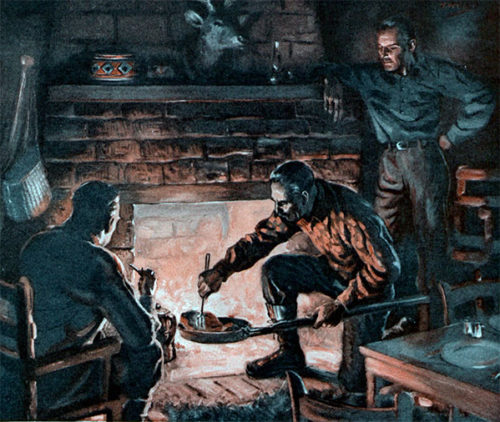

The possum is more than an animal in the South; he is a distinctly American institution, and there the term opossum is considered an affectation. Many Northerners think of the possum as being eaten only by the plantation help. But those fortunate enough to sample the famed hospitality of the South, as it flourishes in rural regions, find that possum and sweet potatoes is also big-house fare. The chief difference is that the white folk bake theirs in an oven, while rural African Americans so often cook on the hearth with an open fire, suspending the possum on a wet string before a high bed of hickory coals. The twisting and untwisting string rotates the meat which is basted with a sauce of red pepper, salt, and vinegar. After having eaten possum cooked both ways, I prefer the open-fire method.

There are two golden rules to possum cooking: First, he is good only in freezing weather; secondly, do not serve without sweet potatoes. Preparation is not difficult, but like all wild things must fit the particular animal. Stick the possum and hang overnight to bleed. Next morning fill a tub with hot water, not quite scalding, and drop the possum in, holding tight to his tail for a short time so the hair will strip. It is then an easy matter to lay him on a plank and pull out all the hairs somewhat as one would pluck a chicken. After drawing, he should be hung up to freeze for two or three nights.

As a preliminary to cooking, place him in a five-gallon kettle of cold water into which has been thrown a couple of red-pepper pods, if you have them, otherwise a quantity of ground pepper. Remove after an hour of parboiling in this pepper water, throw water out, and refill kettle with fresh water, in which he should be boiled another hour.

While all this is going on, the sweet potatoes should be sliced and steamed. Take the possum out of the water, place in a large covered baking pan, sprinkle with black pepper, salt, and sage, and pack the sweet potatoes lovingly about him. Pour a pint of water in the pan, put the cover on, and bake slowly until brown and crisp. Serve hot, with plenty of brown gravy.

Haunch of Muskrat with Watercress

Muskrat haunches, usually with watercress, grace the French-Canadian farmer’s table often enough to guarantee their value as a worthwhile game dish.

Muskrats must be skinned carefully in order not to rupture the musk or gall sacks; those offered for sale on city markets are a trapper’s byproduct; often indifferent skinning spoils them for cooking. French-Canadians use only the hind legs or saddle, four animals for two servings. After a careful washing, they are placed in a pot with some water, a little julienne or fresh vegetables, some pepper and salt, and possibly a few slices of bacon or pork. After simmering slowly until half done, they are removed to a covered baking pan, the water from the pot is put in with them and baking continued with frequent basting until done.

In Maryland and Virginia, the muskrat is known as marsh rabbit and valued highly as a game dish. Cooks there use the entire animal, soaking it in water a day and night before cooking. Then follows 15 minutes’ parboiling, after which the animal is cut up and the water changed. An onion is added, with red pepper and salt to taste, and a small quantity of fat meat. Just enough water is used to keep from burning, thickening added to make gravy, and cooking continued until very tender.

Trade Thanksgiving Turkey for Roasted and Stuffed Raccoon

Coon is excellent eating if caught in cold weather. In skinning, be careful to remove the kernels or scent glands, not only under each front leg but also on either side of the spine in the small of the back. All fat should be stripped off. Wash in cold water, then parboil in one or two waters; the latter if age warrants. Roasting should continue to a delicate brown. Serve fried sweet potatoes with the meat. The coon, with its reputation of washing even its vegetable diet before eating, is one of our cleanest animals; he will not fail you as a cold-weather game dish if you observe the skinning precaution.

Parboiled Porcupine

In the North Woods the porcupine is a lost hunter’s stand-by, his emergency food supply. But unlike most emergency rations this inoffensive little animal is excellent eating, especially if young, when his flesh is as juicy and as fine flavored as spring lamb. The secret of skinning is to commence at the belly, which is free of quills; start the skin there and it pulls off as easily as that of a rabbit. Parboil for 30 minutes, after which roast to a rich brown or quarter for frying or stewing.

Fowl Cooking

The lower grades of ducks are acceptable eating if correctly prepared for cooking. All waterfowl, even the better ducks, have two large oil glands in their tail, put there by Nature to dress the bird’s feathers; these should always be removed before cooking.

The breasts of coot, rail, and young bittern are always worth serving. Cut slits in the removed breasts and in these stick slices of fat salt pork, then cook in a dripping pan in a hot oven. The rank taste of even fish ducks can be neutralized, unless very strong, by baking an onion inside and using plenty of pepper inside and out.

The meat fibers of all game birds and animals are fine grained, containing very little fat, even though the muscles themselves may be encased in it. For this reason most game recipes mention larding. This consists of laying strips of fat pork or bacon not only on top of the meat, but inserting them in slits cut in the flesh itself to prevent dryness. As a rule, dark-meated game should be cooked rare, so red juices, not blood, flow in carving. White-meated game should be thoroughly cooked. Animals and birds, tough or old, should be parboiled first; such meats are better stewed.

The Way with Turtles

Aquatic turtles are good eating at any time, old guides claiming their flesh has medicinal value. The common snapper is excellent, and preparing is not difficult. Aside from any humanitarian feeling, I do not like the method of dropping the live turtle into a tub of scalding hot water; I prefer to get that wicked head off as quickly as possible. One must carry the brute by its stocky tail well away from flapping trousers. Another man with an ax in one hand and a stick in the other extends the stick atop a convenient log. Hold the turtle near and snap go its jaws over the stick with a grip which never fails to make one realize what it would do to a foot or hand. With its neck extended, down comes the ax. One need have no qualms of pity when dealing with this enemy to wildlife.

After letting the turtle bleed, drop in scalding water, when the outside of the shell will drop right off and the skin can be easily removed. Then cut the supports of the flat undershell and remove it entirely, so the turtle can be easily cleaned. To save cutting the meat out, boil in its cleaned shell a short time, when the meat will drop off. Cut up, boil slowly three hours with chopped onion, or stew with diced salt pork and vegetables.

Freshwater Finds: Catfish, Carp, Eels, and Frogs

Proper preparation makes even our so-called coarse fish good eating. To skin bullheads or catfish, cut off the ends of sharp spines, split the skin behind and around the head, and from this point along back to the tail, cutting around back fin. Then peel two corners of the skin well down, cut backbone and hold skin in one hand while the other pulls the body free.

Carp should be carefully skinned rather than scalded. There is a layer of fat or mud between two skins and only with this removed will the fish be found good eating. Many people condemn catfish and carp as being soft fleshed; which they are if taken from too warm water. But every fish is better caught out of cold water.

Eels can be easily skinned by nailing through the tail at a convenient height. Cut the skin around the body, just forward of the tail, work edges loose, then pull down to strip off the entire skin. To broil, clean well with salt to remove slime, slit down back and take out bone, then cut in 2-inch pieces. Rub these with egg, roll in cracker crumbs or corn meal, season with salt and pepper and broil to a nice brown. To stew, cut in pieces after removing the bone, cover with water in a stewpan, and add a teaspoon of vinegar. Cover the pan and boil half an hour, then remove, pour off water and drain, add fresh water and vinegar as before and stew until tender. Finally drain again, add cream for a stew, season with salt and pepper only, and boil a few minutes to serve hot.

Smothered catfish is beloved [in the South], utilize this ugly but sweet-fleshed fish to advantage. Place a large skinned catfish in the baking pan and slice onions to put on top along with strips of bacon. Sift flour lightly over all, salt and pepper, and place in a heated oven 15 minutes.

Frog’s legs are a delicacy from the first spring days until freeze-up time. The northwoods hunting-camp cook soaks the hind legs an hour in cold water, to which vinegar has been added, as a preliminary to cooking. He then drains, wipes dry, and places them in a skillet of bubbling hot cooking oil. Some Southern tidewater shooting-camp cooks use the entire frog, other than the head; others grill the legs only. A preparation is made of three tablespoons of melted butter, half a teaspoon of salt, and a pinch of pepper. The body or the legs are dipped in this, rolled in crumbs and broiled three minutes each side.

Foraging Plants from Field and Woods

Not to be outdone, our early spring pastures and fields offer many edible greens free for the gathering. Dandelion greens, with a piece of bacon, are still regarded by many as a sure sign of spring. Milkweed shoots, wild mustard, dandelions, dock, and sorrel should be dried immediately after washing, then boiled with salt pork, bacon, or other meat. If on the old side, parboil first in water to which a little soda has been added, then drain before boiling again in plain salted water.

Perhaps you have cooked these wild things and not been satisfied with the results. Try chopping the boiled greens fine, then putting in a hot frying pan with butter, pepper, and salt, and stirring until thoroughly heated.

The tender stems of young brake or bracken [fern], cooked same as asparagus, are equally as good as that much-sought-after vegetable. The plants should not be over 4 inches high when they will show but a few tufts of leaves at the top; if much older they are unwholesome. Wash the stalks, scrape, and lay in cold water for an hour. Then tie loosely in bundles and put in a kettle of boiling water to boil three quarters of an hour, when they should be tender. Drained, laid on buttered toast, dusted with pepper and salt, and covered with melted butter they are as good as asparagus, some claim even better.

Wilted dandelion greens call for a peck of fresh tops and half a dozen strips of bacon. Fry the bacon until crisp, then crack into small pieces and pour with drippings over the washed leaves.

Botanists tell us over a hundred edible plants grow wild in our fields and woods. While we may find it easier to raise cultivated vegetables than to gather wild things, it is good to know we live where Nature offers this wholesome fare.

My Wife Wants a Japanese Bidet

Whenever a delivery service leaves a cardboard box on our front porch, I know I’m in trouble, because it’s usually something expensive that requires tools I don’t have.

On a recent Thursday night, Kathy and my in-laws were in our kitchen, ready for our weekly card party. “What’s in the box?” I asked nervously, referring to a package on our kitchen counter. She turned to me and made a face that my in-laws couldn’t see.

“It’s that cleaner,” she said.

“What cleaner?” I asked, because I’m stupid and haven’t learned when to simply shut up.

“That cleaner,” she said, with that slight hiss in her voice that lets me know to back off. “The one I already told you about.”

Ah yes, the … er, cleaner. She was being discreet in front of family, but in fact she was referring to a contraption called a Japanese bidet, a device that mounts to a toilet bowl and shoots a water spray to clean your private parts. Much loved in Europe, bidets are generally freestanding plumbing fixtures positioned next to a toilet. In Japan, however, owing to the small size of most homes, a separate fixture is impractical.

Kathy had found one online for only $30 and placed the order. But I perceived a potential problem, and it had to do with water temperature. The water source for most toilets is cold. While this unit could indeed operate with warm water, as most Japanese bidets do, the hot-water source in our bathroom was too far away to be connected to the device.

“That’s okay,” she said. “Cold water is fine.”

I thought, Famous last words.

So Saturday morning found us at Berger’s Hardware to buy a flexible tube to connect the bidet to the water outlet. I nearly bought one the wrong length, not realizing I would have had to put a kink in it to fit — and possibly choke off the water. Thankfully, I listened to the advice of Berger’s plumbing supervisor and bought a long tube that I could loop and easily attach at both ends. “Trust me,” he said. “I’ve spent a lot of time with toilets. You want to loop that tube.

Definitely. Loop the tube.”

Plumbing and I have never really seen eye to eye. In order to get down to business, I have to screw up my courage somewhat. I get all the tools I’ll need and lay them out on an old towel. I read the instructions for whatever fixtures I’m installing. (I’m basically procrastinating, is what I’m doing.) Ultimately, I take a deep breath and set to it. In my plumbing mindset, I expect my wife to be my assistant, as in, “Hand me that wrench, dear.” “This one? Here you go, sweetheart.” In reality, when I ask for the wrench, the response is more likely to be that I shouldn’t use a wrench, that the nut should only be finger-tight, and besides, that wrench is so old, we should get rid of it, and don’t forget we’re going to the Svensgaards’ on Sunday for dinner.

Fast-forward to three hours later. Somehow, I managed to make all the connections. And then came time for the test. Kathy nodded toward the hallway and said, “Out,” and shut the door behind me. A minute passed. Two.

“What’s it like?” I called out. “Is it working? More importantly, is it leaking?”

Silence.

I knocked on the door. “Kat? You all right? Is it working?”

The door opened, and there stood Kathy. “I like it,” she said and smiled. “I admit I’d like it better if it shot out warm water, because that blast of cold water is sure gonna wake you up on a winter morning.”

“But — you like it?”

“I love it,” she said. “And I know it was a lot of hassle for you, so thank you, Sparky.”

She reached out her arms and hugged me. So yes, it was worth it — for both of us.

Mark Orwoll is former international editor of Travel + Leisure. Listen to Mark read this essay.

This article is featured in the July/August 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Make Vegetables Great Again!

American eaters can be truly adventurous, ready to try out a new restaurant, a new barbecue recipe, or a new foreign cuisine. We just aren’t adventurous enough to make fruits and vegetables a standard in our daily diet. According to a recent survey, only 4% of Americans are eating enough vegetables.

Perhaps our diet is still being shaped by our historic reliance on meats and starches. For so long, the American diet was restricted to what was immediately available. When fruits and vegetables went out of season, we had a choice: wait for spring or open a jar of preserves.

By the mid-1800s, though, iceboxes enabled some cooks to keep foods fresher longer. And when refrigeration made it to transportation and into the home, fruits and vegetables could travel farther and last longer before going bad. Although this gave the average American the ability to eat more vegetables, it didn’t give them much of a reason to.

Because getting fresh produce is one thing; knowing how to cook it well is another.

As food writer and restaurant owner George Rector points out in “Rhapsody in Greens,” vegetables are usually so overcooked that they arrive on the dinner table with little flavor or nutrition left. His informative and humorous 1935 article explains the proper way to cook a vegetable so it can be “as cheering to the soul as it is beneficial to the body.” He also encourages readers to try obscure greens, such as finocchio, fiddle-neck ferns, and beet tops.

Rhapsody in Greens

By George Rector

Excerpted from an article originally published on November 2, 1935

Thanks to scientists, everybody is now aware that you have to eat green vegetables to keep healthy. But science hasn’t bothered — which may be a good thing in a way, since you can’t cook with a test-tube mind — to be equally enterprising about ways of making green stuff as cheering to the soul as it is beneficial to the body. There is no sorrier sight this side of the grave than the standard vegetable plate. And yet its unappetizing presentation is as much of a “must” in modern life as gas for the car, not to mention its yeoman service in keeping the feminine waistline within the bounds of fashion, if not of reason.

Now You’ll Like Spinach

Vitamins and reducing between them have done for vegetables what Tex Rickard did for prize fighting. But the gastronomical angle has been shockingly ignored during the build-up, much as if falling in love were being widely recommended as merely good for the stunted ego. That kind of spectacle makes you see what foreigners mean when they complain that Americans eat what they’re told is healthful, with no thought of the taste. That doesn’t happen to be true, but in certain lights the evidence looks damning.

Spinach is the proverbially tasteless vegetable — in toy shops they even sell spinach toys for bribing the young into eating it — but it’s also true that peas and string beans and cabbage and carrots and all the other green vegetables can be, and often are, as dull as last year’s phone book and as subtly flavored as a cardboard box. The human palate, a finicky faculty which is more precious than rubies, has every right to rebel at wet green hay for food; particularly since it’s thoroughly unnecessary. There is too little understanding of the simple fact that cooking your spinach without water, except that which clings to the leaves, trusting in its own ample juices, retains the flavor essences that make it the joy of real epicures; or that cooking a ham bone with it cheers up both food and feeder; or that, to get into the fancier touches, chopping and creaming it or serving it with poached eggs and grated cheese as eggs Florentine will make the rankest spinach hater wonder where it’s been all his life. Any one of those dodges is a dramatic demonstration that green vegetables provide half the finest flavors known to man, but to get those flavors, you have to treat your raw materials like ladies.

Eating in Foreign Lands

Some travel for health, some for lack of something better to do, some because a travel agent sent them a folder about the joys of winter sports in Tierra del Fuego. But one of my reasons for going to distant places is the prospect of new things to eat. And vegetables are the gastronomic explorer’s long suit. Sheep, hogs, cattle, and chickens are more or less alike everywhere, and a national cuisine can throw variety into them only by varying the cooking process — it’s just a question of boiled sheep’s tails in Afghanistan and roasted sheep’s legs in Simpson’s-on-the-Strand. But, although I’ve since met it on Italian pushcarts in New York, I had to go to Italy for my first meeting with finocchio, that crazy plant which looks something like celery and tastes far too much like licorice; not an experience you want to repeat often, but all in a good cause. I don’t even know the names of some of those futuristic Japanese vegetables which are grand when cooked into suki–yaki, but when pickled in the fiendish Japanese fashion produce much the same effect as a Jerusalem artichoke soaked in kerosene and then left to ripen in the bottom of a fisherman’s dory for two months. I haven’t met the Polynesians’ poi in person, but someday I’ll be digging my left fin into a mess of it, served by a young lady in a grass skirt, and checking it off in my memory along with bamboo shoots and fiddle-neck ferns and the kind of peas that the French cook pods and all. Also I have still to meet the boiled hops which are said to be still eaten in little-frequented parts of England. My natural affection for hops and all their consequences leads me to look forward to that with some pleasure.

The Fiddle-Neck Fern as Food

Fiddle-neck ferns, by the way, show that this country of ours, in spite of all fads, fancies, and foreign aspersions, manages to retain a fundamentally sound attitude toward eating. The fiddle-neck fern is the young shoot of the ferns that grow in the Maine woods, cut by the astute native while still light green and tender, and cooked like greens; the name deriving from the fact that a young fern shoot is all curled up at the end like one of those rolled-up paper tubes they blow in your face on New Year’s Eve. They taste, simply and beautifully, like the soul of spring. Spring, of course, is the queen season of the year for dyed-in-the-wool greens lovers, as well as for poets and the manufacturers of tonics, and a man who has acquired a real taste in the subtle bitternesses of wild greens is well on the way to being a genuine and home-grown epicure. For him the return of the sun means the return of horseradish and turnip and mustard and radish greens, some of which, like mustard, are so bitter that they’re better mixed with something mild like chard — a stepping down of flavor which is only the proper treatment, like mixing Scotch with water. It’s a special taste, but no one is ever happier than a greens hound crawling round a vacant lot on a warm spring afternoon, wielding a blunt knife in the pursuit of young leaves of dandelion and mustard.

If pushed, he will put up with such domesticated but rare items as chicory and endive greens, and will babble by the hour about the glories of young beet tops. The amateur gardener naturally thins most of his beets, so the survivors can develop to the proper size for ordinary cooking. But he can probably afford to let a row or so grow a little further without thinning, till they’re around five inches high, then root up the whole works, tiny beet and all, wash it thoroughly, nip off the thready tail of the little beet — only the tail to keep from “bleeding” it — and cook the whole plant to the tender point in as little water as possible, along with the indispensable ham bone or piece of fat bacon. There is a distressingly rare dish which is as healthful as it is comforting. Sometimes you can get beet tops in the markets, but they’re seldom young enough to give you the last fine careless rapture of flavor, and besides, it’s the lingering sweetness of the miniature beet on the end which adds the crowning touch. Very young beet greens are available in the markets in the early spring and are most delicious when tenderly steamed and served au beurre.

When I think of how any and all greens are abused by the average cook, I feel like taking out a charter for an S.P.C.G. [Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Greens]. Ordinary greens are always more or less gritty, because the lady in charge didn’t know about washing them by soaking in gallons of cold water, with the greens floating on top and the dirt sinking far below to the bottom, and then not pouring them out with the water into the sink, but lifting them off the top. They’ll be flavorless because she drowned them in water while boiling, and then drained the water off. As I’ve already mentioned somewhat querulously, spinach needs only the water which clings to the leaves. And one of the better ways to handle kale and beet tops is to treat them as you would spinach: Cook them for five minutes with water that clings to the leaves, then drain and pitch them into an iron pan in which some fine chopped bacon — easy on the bacon — has been sizzled just enough to start the fat rendering well. Cover that tight, let the natural juices do the cooking until your greens are tender, and you have something as extra in its own way as fine old brandy.

Putting Steam to Work

When you’ve developed your courage by doing spinach without water, try peas with lettuce leaves and discover just how delicate the pea can be when properly educated. The best receptacle for this job is a heavy metal pot with a tight-fitting lid and a good six inches of depth — iron, copper or aluminum, it doesn’t matter so much if the metal is good and thick. Wash your shelled peas and allow as much water as possible to cling to them. Then put a tablespoon of butter, without melting it, in your deep pot and introduce the peas. Cover the peas with some large lettuce leaves that are dripping wet, clamp on the cover, set it over the low flame and let the water on the lettuce and the natural moisture of the peas work up a bland but efficient steam, then immediately reduce the heat. This method cooks everything to a point of tenderness you never met before. The lettuce is thrown away before serving, but its soul remains behind in the flavor. You may prefer to introduce some chopped onion before steaming or to dust the peas with a little sugar after they hit the pan — I recommend both — but don’t miss the main and significant point, which is the consequences of steaming, not boiling.

The more I fiddle with food, the more thoroughly I am convinced that steaming is the best way of tackling most vegetables. It keeps in vitamins and flavor both, which means that here is a process satisfying both dietitian and gourmet, who are usually clawing at each other’s throats. A capacious vegetable steamer belongs in every right-thinking kitchen, along with a drip coffeepot and a pepper mill and a wooden salad bowl anointed with ancient garlic and all the rest of my idées fixes in the way of cooking equipment. And a steamer with several compartments makes it possible to combine several vegetables, with a minimum of trouble. A mixture of peas, young lima beans, and string beans, piping hot from the steamer and covered thickly with heavy cream that’s been whipped just enough to start thickening, or that grand old American dish, succotash, which, in its finest version, consists of fresh lima beans and green corn cut off the cob, seasoned with butter, salt, and pepper after steaming and then cooked for a few decisive minutes in cream.

Steamed cabbage, doused with butter, salt, and pepper before serving, can alone cause revolutions in people’s attitude toward that plebeian plant — the kind of people who really get the horror of that melancholy statement made by Walter Hines Page, the wartime ambassador to England, to the effect that there were only three vegetables known in England, and two of them were cabbage. I always think of cabbage, though, as a shining example of how something intrinsically first-rate can get a bad name through mistreatment. The American male has every reason for his notorious affection for corned beef and cabbage, but, when it’s either neglected or ruined when attempted, he prefers to leave it as just a glorious memory. It may do no good at all, but here goes for the resurrection anyway: I know a man who can make corned beef roll over and make a noise exactly like Virginia ham when he bakes it, and when he combines it with cabbage, the stars in their courses stop rolling to take a sniff. According to him, the secret lies in starting your beef in cold water and never letting it reach a fast boil, just a gentle simmer for the period, somewhat under four hours, you’ll want for a five-pound piece, starting with cold water. And he insists on skimming the fat off the water at least twice during the boiling. The cabbage should be sliced across the bottom to cut loose the first layer of leaves, and then quartered. Half an hour before the beef will be done, in she goes, to simmer along with her soulmate; and I recommend including half a dozen grains of whole black pepper. English mustard as a relish for it is a universal note, but chopped onion sprinkled over the plat is a preference of my own that you might take to. It sounds almost too simple to go wrong on, but it’s a mortal fact that the results of misguided at- tempts often remind you of the cowboy in The Virginian who said, on trying the corned beef, that it felt like he was chewing a hammock.

Meet Bubble-and-Squeak

A first-rate version of this dish will make your wife look thoughtful after the second bite and admit after the third that it isn’t bad at all. When she’s been softened up, get her to throw you some bubble-and-squeak for Sunday breakfast. Cabbage boiled to death and potatoes ditto are two of the pillars of British civilization and two disgraces to a civilized nation, but the Englishman who first fried the two together was a genius — never mind the name. I first met the results in the days when Rector’s was booming enough to supply my father with a yacht — a two-masted schooner which floated quite as well as Mr. Morgan’s — named the Atlantic. One summer the Atlantic boasted a Portuguese cook who was nothing to boast of. The old gentleman was pretty finicky about food, as he had every right to be, and, at breakfast one morning, he was just telling me he’d made up his mind to fire the Portygee and get somebody who knew how to boil water at least, when in came the steward with a small platter of piping hot bubble-and-squeak. Father hung his nose over it a moment — it had been browned just right in a minimum of mixed bacon fat and butter — glanced suspiciously at a forkful, stowed it, swallowed it, rolled up his eyes, and instructed me to go out to the galley and tell the Portygee that his pay was raised five dollars a week.

Or, moving over into red cabbage, which isn’t quite comfortably domiciled in some sections of the country yet, combine it with apples and red wine — a German idea, and a beauty.

Shred an average-sized, firm head up fairly fine and bestow the shreds in that same tight-lidded, heavy pot we’ve been talking about, along with four apples pared and sliced, three tablespoons of butter, a quarter cup of vinegar, a third of a cup of sugar — brown sugar preferred — a teaspoon of salt, a light pinch of cayenne — that red-headed and indispensable devil — and a cup of any old red wine, domestic or imported. After that it’s just two hours of simmering in its own juices over a low flame — with the wine and the butter she can’t burn — and, when that gets to the table, you may begin to understand the Egyptians, who worshiped red cabbage along with Isis and Osiris.

The Romantic Tomato

In his pursuit of the higher life, the overmoral vegetarian is also apt to forget the ornamental properties of vegetables. Painters don’t. No painter ever goes for long without tearing off a still life consisting of three carrots, an onion, a big red tomato, and a basket of Brussels sprouts, thus emphasizing again the intimate connection between high art and a boiled dinner. Certainly this question of looks had a lot to do with the past of vegetables. The business of putting a pinch of soda in with green peas and beans to give them that awful Paris-green color I do not approve. I suppose eating with your eyes is all right if you like it, but my own tastes don’t run that way. But things like tomatoes and eggplant might never have got anywhere if they hadn’t been cultivated as garden ornaments because they were handsome, long before they reached the table. In its ornamental period, the tomato was known as a love apple — the name being an outrageous example of mistranslation. When the Moors first brought tomatoes into Sicily, the Sicilians called them pomi di Moro — meaning “Moor’s apples.” Then the French met them under that name, and thought they were saying, pomi d’amore, meaning “apples of love.” So it got into French as pommes d’amour, and into English as “love apples.” As a natural consequence, tomatoes got a wholly undeserved reputation as something good for making the girlfriend fall in love with you — and so, for all I know, the first man who ate a tomato and found it was delicious was merely trying to work up his nerve to pop the question. He was taking a desperate chance, just the same, because tomatoes were long supposed to be poisonous.

After which dazzling burst of scholarship, let me point out that, besides both being among the raving beauties of the vegetable kingdom, tomatoes and eggplants are naturally coupled in the betting by being natural partners in gastronomy. Tomatoes are approximately foolproof, but, in general, eggplant is even worse mishandled than greens. Frying it in butter, which is as far as most cooks get, is about as sensible as stewing a nice young broiling chicken. Its delicate sub-bitterness won’t stand such treatment. There’s a way of baking it sliced with lemon juice that does it justice, and eggplant Provençal, which rings in the helpful tomato, is one of the most princely dishes in the Continental cuisine.

Peel your eggplant or not, depending on whether you like the fairly heavy bitterness of its skin. Anyway, slice it crosswise into quarter-inch disks and sauté the slices gently for 10 or 15 minutes in butter. Jean Frenchman includes a shallot with them, and if you can get shallots, more power to you. Sauté your tomatoes cut in half the same way; the number of tomatoes depends on the size of your eggplant. Butter a big flat baking dish and line the bottom with slices of eggplant covered in turn with a layer of tomatoes. Salt, a light pinch of cayenne pepper, and a dusting of grated cheese. Another layer of eggplant ditto, another layer of tomatoes ditto and seasoning ditto. After it’s baked about an hour in an average oven, the liquid that oozes out of the vegetables will be pretty well cooked away and the top beautifully brown. I can turn vegetarian in the presence of this dish and dine on nothing else, if the supply holds out. Along the Riviera they use olive oil instead of butter, of course, and there’s a considerable load of garlic in the makings.

You can do as you like about the garlic, but the butter will richen things up more, even if it does make the sautéing a little trickier.

It’s all in giving your vegetables a break, allowing them a small portion of the same care and forethought that meats receive as a matter of course. Even the lowly carrot, which is so good for you and so dull to eat, can step out as carrots Vichy and go to town as brilliantly as Cinderella. That’s just steaming your carrots along with a bay leaf, draining and letting them cool enough to handle, then slicing as thin as possible and browning in butter, both sides. With a sprinkling of chopped parsley they’re as handsome as they are sweet and juicy. And don’t get the idea, by the way, that parsley is a mere ornament. The other day I did meet a very pretty and charming young lady with a boutonniere of parsley for nothing but ornament, but the fact is that its queer, half-acid, half-musty flavor is the secret of many a famous dish. The French throw in an extra wrinkle in doing carrots Vichy in Vichy water, but between you and me, that’s only an excuse for giving the dish a name.

New Ways to a Man’s Heart

The more you shop around in the inner arcana of cooking, the more you realize that somewhere, sometime, somebody has cooked everything cookable. It never occurs to the average mistress of a kitchen to explore the possibilities of braised celery and endive and lettuce, although the results may go far toward solving the problem of how to get green stuff into Junior, and, more likely than not, the family cookbook contains full instructions for all three. She never heard of the admirable practice of frying thin slices of cucumber in batter as a side partner for fish, or of stuffing a pared and cored cucumber like a tomato. She even allows such reputable country dishes as fried oyster plant, done much the same way as carrots Vichy — you may have to ask for salsify to get it in your town — and wilted lettuce to slide ignored into the discard. Wilted lettuce is a homely thing, native to up-country farmhouses, but it’s the best way of explaining why the conventional salad never took hold on the old-fashioned American cuisine. A bit of chopped bacon in a frying pan, sizzling to a brown, some sharp vinegar and a little sugar thrown in — stand away while she steams and sputters — and then the large leaves of old-fashioned lettuce tossed in and chivvied round in the hot mixture till they’re limp as a wet glove and a rich dark green. The bacon and vinegar and sugar combine into a barbaric symphony of clashing and yet harmonizing flavors, and the lettuce turns out comfortingly chewy and surprisingly suggestive of a second helping. A man who won’t eat cold salads can often be made into a wilted-lettuce addict, which hornswoggles him neatly and painlessly into his share of roughage and vitamins.

Much as I reprehend eating with the eyes, I must admit that there is something in making a vegetable look interesting, which is why a baked stuffed tomato is always regarded with such respect — although it’s good eating, too — and undoubtedly why artichokes have always been among the aristocrats of the vegetable world. The amount of nourishment you get from artichoke leaves could be put in your eye with no inconvenience whatever and, unless you regard them as I do — as a fine excuse for consuming Hollandaise or vinaigrette dressing — the only point is the fascination of pulling them apart leaf by leaf and finding one good mouthful of heart in the middle. That appeals to everybody who ever took an alarm clock apart as a small boy.

Romance and Artichokes

One of our customers in the old days at Rector’s even made use of them in his affaires de cœur. He was always in love with another girl, and, although he was rich and not bad-looking, he was unlucky in love and would come into Rector’s to brood over his troubles alone, parked solitary at a table, without a word to throw at a dog. During one of these private wakes of his, he happened to order an artichoke Hollandaise — and presently the whole restaurant was treated to the spectacle of this young man, totally unconscious of his surroundings, playing “She loves me, she loves me not,” with the artichoke leaves. It got to be a regular thing with every new girl. Maybe artichoke leaves come in pairs — I’m not botanist enough to know — but anyway, he was always coming out on “She loves me not,” even counting the tiniest leaves, and feeling much worse in consequence. Finally a waiter took pity on him and carefully removed one leaf before serving him.

From then on, he came out on “She loves me,” and he would walk out of the place with his head up and his stick swinging and a five-dollar tip left behind on the table, as happy as a little boy with a new pair of red-top boots. He can’t have got much of the flavor of his Hollandaise, which is one of the more delicate consolations for living here below, but then, you have to pay some penalty for being in love. And I suppose you also have to pay some penalty for living, in an age when science gets more attention than flavor. But when I get down to eating by theory, I’ll follow the principle laid down by Dr. Horace Fletcher, the old fellow who invented Fletcherizing and carried it so far that he made his disciples chew even milk thoroughly before they swallowed it. As that would indicate, he was something of a crank. But he did write these noble words: “Trust to nature absolutely. … If she calls for pie at midnight, eat it then.” I’d like to be there and have a piece with him.

You can find out more about the Rectors and their famed New York City restaurants at The American Menu.