Let’s Make Football a College Major

On a fall day in 2012, right after taking a frustrating sociology exam for which he would receive a B, Cardale Jones – a student-athlete at Ohio State University – tweeted something that he would later regret:

Jones saw college as football and classes as an inconvenience. At the time, and again two years later when the quarterback led his team to a national championship, Jones’s tweet brought intense criticism. But maybe it shouldn’t have.

College football players spend more than 40 hours per week on football, including time on the practice field, in the weight room, with trainers, and in film study and team meetings. On average, college athletes spend more than 30 hours a week on their sport. The US National Collegiate Athletic Association has a rule limiting college athletes to 20 hours per week, but it is rife with loopholes and a target of lawsuits.

Such ambitious schedules leave college athletes exhausted and with little energy for coursework. In many cases, the primary reason they are attending college in the first place is to play a sport. Many athletes evince a dedication exceeding all but the most committed students of the sciences or humanities.

In fact, the phrase ‘student athlete’ is redundant. To be an athlete is to be the student of a discipline as rigorous and as noble as literature, chemistry or philosophy. The ancient Greeks, who invented the idea and practice of the academy, conceived of athletics as a basic component of education and culture (paideia).

Ancient precedents aside, any college course catalogue today reveals many majors focused primarily on a physical or practical, rather than theoretical, field of study. The University of California, Berkeley, my alma mater, supports majors in art practice, dance and performance studies, theatre and performance studies, music, film, creative writing, journalism, communications, and business administration. The art practice major consists ‘largely of studio courses’ and focuses on artistic production, although students also take classes in art history, theory and business. All of these majors combine educational requirements of practice and theory, but focus on practice. They provide an obvious model for majors in sport.

The football major, for example, would consist of the practicum, the many hours of physical training, practice, film study and meetings. Courses would also be required in the history, science, criticism and business of the discipline, as well as in the related fields of physiology, nutrition, journalism and sports management. Indeed, all of these fields of study already exist. A graduate of the football major could claim some expertise in the field, and be someone with the potential for significant impact, as an athlete, coach, trainer, agent, commentator, consultant, or team member in a complex organisation.

Some critics might argue that sport is not intellectual enough to be enshrined as a field of academic study. But this objection presumes a much too restricted view of intellect, a proper account of which must also clearly make room for performative activities such as art, theatre and dance. Thanks to recent scientific and academic research, we have a much better appreciation of the intelligence required for athletic excellence.

Sport intelligence requires cognitive performance that is extremely demanding: the ability to read the complexity of a situation, to come to near-instantaneous intuitive judgments about how to react, and to move the body accordingly. It requires, as the journalist Chuck Squatriglia explained about soccer research in Wired, ‘what neuropsychologists call executive functions, which include the ability to be immediately creative, see new solutions and quickly change tactics’.

In this respect, the demands of football are especially rigorous. Because it involves large teams with 22 players lining up on any one play to perform a strategic manoeuver, if on offence, or to counter that manoeuver, if on defence, it requires more preparation off the field than any other sport. American football players spend more time in meeting rooms, watching film and reading binders of plays than doing anything else. As Nicholas Dawidoff wrote in The New Yorker:

In developing a game plan, coaches typically break down everything that happened in the opponent’s past four games to granular levels of ‘tendencies’ – down, distance (to a first down), field position, and time remaining on the game clock. Once assembled, this research fills many pages of the game-plan binders players are given on Wednesday to prepare them for Sunday. (Teams have also begun to use iPads.) The binders are dense with intricate drawings and written instructions. They are often as thick as a left tackle’s fist.

What players learn is then tested under high-stress real-world conditions, in practice and actual games. How many fields of study can say the same?

I would also argue that people suffer from an impoverished view of the human mind. The popular tendency is to think of consciousness as something that happens inside the head or the brain, but philosophers are challenging this view with an approach that sees the mind as the interaction of one’s entire neurological system with the environment. The US philosopher Alva Noë, for example, who has written several books exploring a new theory of mind, appeals to practices such as dance, which demonstrate how mental activities can be bodily and spatio-temporally extended, coordinated and social, and both reactive to and manipulative of other people and the world. And psychologists such as Howard Gardner have theorised that kinaesthetic intelligence, the ability to use the body to solve problems, is a distinct form of intelligence worth study.

While these distinctions might be unfamiliar to many, people do seem to recognise the unique intelligence of athletes and how that intelligence can translate into other domains. Businesses, law firms and other complex organisations requiring a sophisticated balance of competition and cooperation often recruit from college athletics, especially from team sports.

Creating sports majors also addresses real problems. Unlike philosophy or anthropology, sport is a booming multi-billion dollar industry in the United States and around the world. It offers potential for employment in an extensive variety of fields: coaching (high school, college, pro), physical training, marketing, law, consulting, design, management, and more. Sports majors would help athletes to succeed in these fields. If Cardale Jones, for example, does not make it in the National Football League, his next-best options might be as a football coach, trainer, agent or businessman.

For at least a century, US universities have decided to include athletics in higher education, and that is not going to change. Nor should it. We just haven’t pursued the logic to its proper end. It is time to make football a major.![]()

David V Johnson

This article was originally published at Aeon and has been republished under Creative Commons.

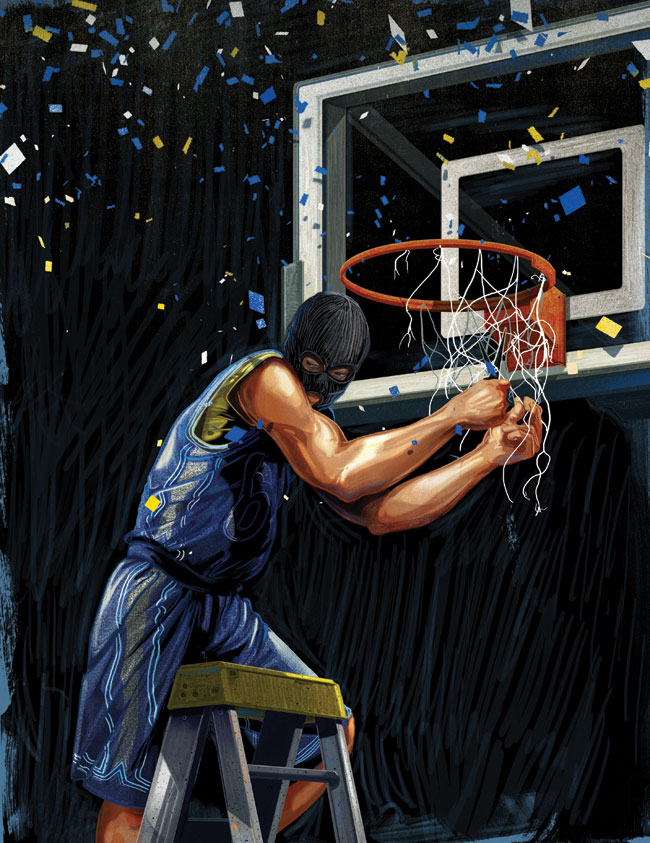

Cheating in College Sports

You can bet on it: Where there’s sports, there’s gambling. And where there is gambling, frequently there is cheating. In just one of the most recent scandals, former University of San Diego basketball star Brandon Johnson and seven others were convicted of “altering” games and sent to federal prison: Johnson was sentenced to six months in a federal facility.

Gambling on collegiate sports, an estimated $100 billion-a-year industry, is increasing every year, according to Albert Figone, author of Cheating the Spread: Gamblers, Point Shavers, and Game Fixers in College Football and Basketball. The problem of cheating is exacerbated by the increasing commercialization of collegiate sports and the huge amounts of money made by universities at the expense of underpaid student players. Case in point: Texas, the number one earner, generated in excess of $163 million from its sports programs in 2012.

With millions of dollars swirling around them, some college athletes see themselves as pawns in a system that exploits their talents. “These high-performing athletes have been trained for over 10 years and now work for the equivalent of $8 per hour based on the value of their scholarship. Sometimes they are vulnerable to gamblers who approach them with payoffs,” says Figone.

“Fixing a college game is like shooting fish in a barrel,” says Brian Tuohy, author of The Fix is In. “You can pretty much fix any college game you want to. And it wouldn’t take a lot of money to do it.”

Most college stars will never see the pot of gold associated with an NBA contract, and they know it. “At top-ranked programs, there may be two guys on the team who will end up in the NBA,” says Tuohy. “But then you’ve got a third senior who is a starter with no hope of going pro and no prospects for earning the big bucks pros make. What if you go to him and say, ‘Hey, look, I’ll give you 10 grand a game to make sure you don’t cover the spread’?”

The spread, or point spread, is essentially a gambling handicap favoring the underdog team. Rather than a straight win-or-lose proposition, the wager becomes “Will the favorite win by more than a given number of points?” A player on a team favored to win can intentionally blow a layup or miss a free throw to “shave points” off the score so as not to beat the spread. In doing so, his team can win the game while still enabling his corrupt paymasters to win their bet on the opposing team. This kind of cheating can be difficult to discern, though it frequently leads to a certain amount of lead-footed play. According to an FBI report presented at Brandon Johnson’s trial, the athlete “was heard on electronic surveillance talking about how he wouldn’t shoot at the end of a particular game because it would have cost him $1,000.”

How widespread is cheating? Figone estimates fixing the outcome of games involves only about 1 percent of the roughly 430,000 collegiate athletes. “Although the percentage may sound small, that still means more than 4,300 college athletes may be asked to influence the outcomes of games in some way,” he says. A March 2012 NCAA survey of collegiate athletes supports his estimate. Of 23,000 student athletes, about 5 percent of Division I men’s basketball players and 2 percent of Division I men’s football players admitted to having been “contacted by outside sources to share inside information.” Around 1 percent admitted to “providing inside information to outside sources.”

Gambling is like a dark cloud enveloping college athletics. Bookies and professional gamblers hang around college campuses in order to approach players about upcoming games, and the players know exactly what’s happening, even the honest ones. “I have not talked to one college basketball player who did not know the line [point spread] on the game he was playing,” says a Las Vegas-based bookie who agreed to be interviewed on the condition of anonymity.

Still, most experts say the vast majority of players are honest. “I am sure gambling or fixing collegiate games happens five times more often than you hear about. But it’s still the exception and not the norm,” says James Whitford, head basketball coach at Ball State University and former associate head coach of the 2013 University of Arizona basketball team that went to the Sweet 16.

Certainly there is awareness at the schools that the danger of cheating is very real, and the NCAA has launched initiatives to combat corruption. For example, all teams making it to the Sweet 16 in the NCAA basketball tournament are visited by FBI agents who warn them about the risks of collaborating with gamblers.

But a few strong words and even the legal consequences of violating the rules are not enough to stop all cheating. “It’s almost a perfect storm for criminal conspiracy when you’ve got young athletes with uncertain futures and financial hardships who feel they’re not going to be hurting anybody if they shave a few points,” says David Schwartz, director of the Center for Gaming Research at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.