Cheating in College Sports

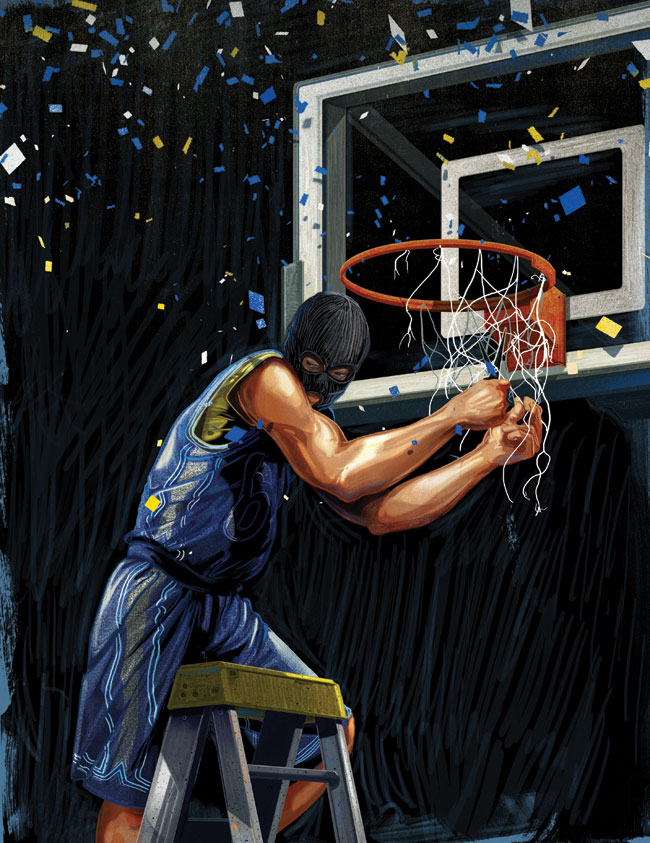

You can bet on it: Where there’s sports, there’s gambling. And where there is gambling, frequently there is cheating. In just one of the most recent scandals, former University of San Diego basketball star Brandon Johnson and seven others were convicted of “altering” games and sent to federal prison: Johnson was sentenced to six months in a federal facility.

Gambling on collegiate sports, an estimated $100 billion-a-year industry, is increasing every year, according to Albert Figone, author of Cheating the Spread: Gamblers, Point Shavers, and Game Fixers in College Football and Basketball. The problem of cheating is exacerbated by the increasing commercialization of collegiate sports and the huge amounts of money made by universities at the expense of underpaid student players. Case in point: Texas, the number one earner, generated in excess of $163 million from its sports programs in 2012.

With millions of dollars swirling around them, some college athletes see themselves as pawns in a system that exploits their talents. “These high-performing athletes have been trained for over 10 years and now work for the equivalent of $8 per hour based on the value of their scholarship. Sometimes they are vulnerable to gamblers who approach them with payoffs,” says Figone.

“Fixing a college game is like shooting fish in a barrel,” says Brian Tuohy, author of The Fix is In. “You can pretty much fix any college game you want to. And it wouldn’t take a lot of money to do it.”

Most college stars will never see the pot of gold associated with an NBA contract, and they know it. “At top-ranked programs, there may be two guys on the team who will end up in the NBA,” says Tuohy. “But then you’ve got a third senior who is a starter with no hope of going pro and no prospects for earning the big bucks pros make. What if you go to him and say, ‘Hey, look, I’ll give you 10 grand a game to make sure you don’t cover the spread’?”

The spread, or point spread, is essentially a gambling handicap favoring the underdog team. Rather than a straight win-or-lose proposition, the wager becomes “Will the favorite win by more than a given number of points?” A player on a team favored to win can intentionally blow a layup or miss a free throw to “shave points” off the score so as not to beat the spread. In doing so, his team can win the game while still enabling his corrupt paymasters to win their bet on the opposing team. This kind of cheating can be difficult to discern, though it frequently leads to a certain amount of lead-footed play. According to an FBI report presented at Brandon Johnson’s trial, the athlete “was heard on electronic surveillance talking about how he wouldn’t shoot at the end of a particular game because it would have cost him $1,000.”

How widespread is cheating? Figone estimates fixing the outcome of games involves only about 1 percent of the roughly 430,000 collegiate athletes. “Although the percentage may sound small, that still means more than 4,300 college athletes may be asked to influence the outcomes of games in some way,” he says. A March 2012 NCAA survey of collegiate athletes supports his estimate. Of 23,000 student athletes, about 5 percent of Division I men’s basketball players and 2 percent of Division I men’s football players admitted to having been “contacted by outside sources to share inside information.” Around 1 percent admitted to “providing inside information to outside sources.”

Gambling is like a dark cloud enveloping college athletics. Bookies and professional gamblers hang around college campuses in order to approach players about upcoming games, and the players know exactly what’s happening, even the honest ones. “I have not talked to one college basketball player who did not know the line [point spread] on the game he was playing,” says a Las Vegas-based bookie who agreed to be interviewed on the condition of anonymity.

Still, most experts say the vast majority of players are honest. “I am sure gambling or fixing collegiate games happens five times more often than you hear about. But it’s still the exception and not the norm,” says James Whitford, head basketball coach at Ball State University and former associate head coach of the 2013 University of Arizona basketball team that went to the Sweet 16.

Certainly there is awareness at the schools that the danger of cheating is very real, and the NCAA has launched initiatives to combat corruption. For example, all teams making it to the Sweet 16 in the NCAA basketball tournament are visited by FBI agents who warn them about the risks of collaborating with gamblers.

But a few strong words and even the legal consequences of violating the rules are not enough to stop all cheating. “It’s almost a perfect storm for criminal conspiracy when you’ve got young athletes with uncertain futures and financial hardships who feel they’re not going to be hurting anybody if they shave a few points,” says David Schwartz, director of the Center for Gaming Research at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.