Philip Wylie: The Unsung Hero of Super-Heroes

The annals of history overflow with the overlooked. Some people were incredibly famous in their time, but have faded from view even as their influence abides. Philip Wylie might be one such person. A prolific writer of novels, nonfiction, screenplays, essays, and articles (many of which were for The Saturday Evening Post), Wylie may be most famous for his 1943 book, Generation of Vipers, which essentially attacked every American institution from religion to government to mothers. In genre fiction circles, he’s most well-known and remembered for his novels like Gladiator, The Savage Gentleman, and When Worlds Collide. Those books left an indelible mark in their field and planted seeds that would become the avatar of America’s popular mythology: the super-hero.

Wylie’s life as a writer is hard to categorize. His work covered a broad area, touching many disciplines and topics. Whereas some working writers find their genre and stick to it (with occasional divergences into other styles), Wylie wrote just about everything. Born in 1902 to a minister father and a writing mother who died when he was five, Wylie had a keen interest in science and philosophy as well as literature.

The interest in science would be applied regularly to his writing, particularly, and unsurprisingly, to his science fiction work. His first two novels, Heavy Laden (1928) and Babes and Sucklings (1929), were both described as comedies of manners, with the first leaning heavily on details from his own life (one of the main characters has a minister father). 1930’s Gladiator leaned all the way into the science fiction genre. The main character is Hugo Danner, a man who is born with enhanced strength, speed, and invulnerability after his scientist father injects his pregnant mother with an experimental serum. Danner uses his strength for money-making endeavors, but eventually joins the French Foreign Legion to fight against Germany in World War I. The book has stayed in print over the decades; Marvel Comics adaptated the first half of the novel in Marvel Preview #9 in 1976, with legendary comics writer Roy Thomas handling the writing duties.

Roy Thomas’s manager, John Cimino, arranged for the venerable writer to discuss Wylie and why Thomas wanted to adapt the story. Thomas says, “The fact that it was such a seminal influence, I felt, on the concept of the super-hero… even though it in turn was probably influenced by the likes Edgar Rice Burroughs’ John Carter of Mars novels and John Campbell’s story/novel The Mightiest Machine… made me want to adapt it at Marvel, even though I only got the chance to adapt the first half of it before I left Marvel for a time in 1980.”

On the broader subject of Hugo Danner as an influence on Superman, who didn’t appear in Action Comics #1 until 1938, Thomas says, “I know that [Superman co-creator] Jerry Siegel never admitted to a direct inspiration from Gladiator, but I have always pretty much discounted that as being said for legal reasons. After all, Jerry was a prominent and wide-reading SF fan in the 1920s and ’30s.” Thomas went on to say that some occurances in the novel were very similar to scenes from the novel, with both seeing the leads avenging wrongs and pushing back against bad businesspeople.Thomas says, “I can accept the general idea that the similarities may have been a coincidence, but I find it impossible to believe myself.”

Thomas would later get the chance to take advantage of Gladiator’s public domain status and incorporate Hugo Danner into his Young All-Stars comic at DC in the 1980s. One of the lead characters was young super-strongman Iron Munro, and Thomas canonized Hugo Danner as Munro’s father. Thomas says, “I knew that Arn Munro had been the super-human hero of Campbell’s novel/story The Mightiest Machine in Astounding Stories . . . an Earthman raised on Jupiter and thus gaining great strength and leaping abilities when he returned to his native Earth… Clearly, here was another possible inspiration for Superman, though it came later than Gladiator… so I decided that Arn Munro should be the son of Hugo Danner.”

Thomas pretty clearly sets a line of lineage from early science fiction novels through Gladiator and onward to Superman. But Gladiator wasn’t Wylie’s only novel to have a huge impact on comic and pulp heroes. His 1932 novel, The Savage Gentleman, sports more than a few similarities to a hero that would debut a year later in his self-titled magazine, Doc Savage. In The Savage Gentleman, Henry Stone is raised on an island by his father and two of his father’s servants and returns to a 1930s New York an incredible physical specimen with a fortune waiting for him; his hair is even described as “bronze.” Doc Savage, nicknamed “The Man of Bronze,” was an Olympic-level athlete and an expert at everything after being trained by men chosen by his father. As Thomas says, “[I]t was amusing to learn later that Wylie had also written a book titled The Savage Gentleman, who some see as influential on Doc Savage… who in turn was called a ‘Superman’ in ads before DC’s comic hero emerged… and was known as ‘the Man of Bronze,’ where Superman became first the ‘Man of Tomorrow,’ but soon the ‘Man of Steel.’”

In 1933, Wylie turned his attention to the stars for one of his best-remembered novels, When Worlds Collide. The story, co-written with Edwin Balmer, deals with a scientist discovering that two rogue planets may destroy Earth and the steps taken to try to save the population. As explained in the 1990 book, Flash Gordon: Mongo, the Planet of Doom, the novel was a direct influence on Alex Raymond, who took central plot elements of Wylie’s and created and drew the newspaper comic strip Flash Gordon the following year. The lineage of When Worlds Collide resonates through many branches of pop culture, as George Lucas has repeatedly identified Flash Gordon as an immediate influence on Star Wars.

The trailer for When Worlds Collide (Uploaded to YouTube by YouTube Movies)

Wylie’s work in those three novels formed the foundation for thousands of super-hero characters that come after them. Hugo Danner is the science fiction super-human, like Superman. Henry Stone is the pulp hero, a product of training backed by wealth, like Doc Savage and, later, Batman (who himself owes debts to Zorro and the Scarlet Pimpernel). The leads of Collide are the space heroes, like Flash Gordon, the Hal Jordan Green Lantern, and the Fantastic Four. Those are the starting points for a remarkable number of characters that would follow in four-color comics just a few years later.

As he worked on those novels, Wylie also worked in Hollywood, writing the screenplay for the adaptation of H.G. Wells’s The Island of Dr. Moreau, 1932’s The Island of Lost Souls. He also did uncredited work on the 1933 film version of Wells’s The Invisible Man, which borrowed as much from Wylie’s own novel, 1931’s The Murderer Invisible, as it did from Wells. He also had various other novels adapted into film, like 1949’s Night Unto Night, starring Ronald Reagan.

Over the following years, Wylie would continue to write, well, everything. A past director of the Lerner Marine Laboratory, he wrote dozens of short stories about fishermen Crunch and Des, many of which ran in The Saturday Evening Post, and were packaged in eight collections over time; the stories became a short-lived TV series in the 1950s. The first and most famous of his nonfiction books, Generation of Vipers, landed in 1942, and was (and is) controversial. Amid his attacks on Christianity and Washington, D.C., Wylie put down the lionization of the role of mothers in culture, calling it “momism.” Wylie both supported and walked back various statements from the book over the years, and critics have vacillated between calling that attitude misogynistic or taking a stance others wouldn’t. A Washington Post reassessment from 2005 notes that the book feels more like Wylie was attacking things just because they were there.

Wylie’s fiction continued to draw attention in occasionally surprising ways. His scrupulously researched writing on nuclear weapons (as in The Smuggled Atomic Bomb) was so knowledgeable and precise that he was questioned by the authorities. Ironically, that knowledge base would also earn him a place as an advisor to the Joint Congressional Committee for Atomic Energy. He also had progressive notes in his fiction. In the 1951 novel, The Disappearance, he speculates on what would happen if men and women were suddenly cosmically separated. After a “blink” splits the world into two versions, one of only men and one of only women, Wylie examines how the men-only world begins to decline while the women-only world thrives. He also manages to approach homosexuality, a huge taboo at the time, in light of what happens when there’s only one gender remaining in the world.

At The Saturday Evening Post, in addition to Crunch and Des, Wylie’s pieces covered a predictably huge range of subject matter. He wrote on student performance in college, doctors in Bimini, and surviving hurricanes, among other topics. Portions of his novel, Triumph, about the after-effects of a nuclear war, were serialized in the Post. For other outlets, he wrote about medievalism, career women, UFOs, missile defense, censorship, and the work of Mickey Spillane.

Philip Wylie died in 1971, but his work continues to resonate. His fiction shaped comic books, science fiction, film horror, and more. His nonfiction forced people to reexamine their own opinions. The majority of his work is still in print, even if it’s overlooked by the general public. Aficionados of genre fiction remember him, but the sheer breadth of his contributions isn’t always recognized. At least for now, Philip Wylie remains the unsung hero of super-heroes.

Featured image: Shutterstock

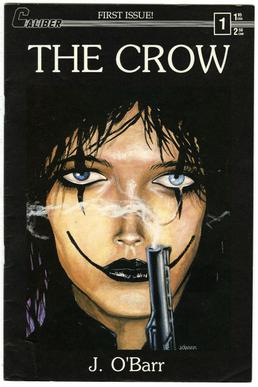

It Can’t Rain All the Time: How The Crow Captured the Angst of a Generation

Arriving in theaters before the decline of the first Batman film franchise and weeks after the death of Kurt Cobain, Alex Proyas’s The Crow, based on the independent comic by James O’Barr, managed to have a lasting impact on film, comics, music, and the soul of a generation. Steeped in a sense of loss that was magnified when leading man Brandon Lee was killed during filming, The Crow emerged as a cultural touchstone due to all of the forces contained in its 102-minute runtime. Now, 25 years later, we look back at why so many pieces of the work still resonate.

1. It’s Personal

A central theme of The Crow is loss, and that comes from a very honest place. O’Barr started working on the story after losing his fiancée to a drunk driver. That tragedy, along with a local news story about a young couple murdered for an inexpensive engagement ring, provided the fuel to O’Barr’s tale of Eric Draven, a man who comes back from the dead to avenge the loss of his own fiancée; the title comes from the supernatural guide that accompanies Draven on his quest.

2. Brandon Lee’s Unfortunate Passing Added a Deeper Layer

Brandon Lee had been a working actor with a cult following for several years when he took on The Crow. The son of film and martial arts legend Bruce Lee, Brandon Lee grew up learning Kung Fu and had expressed an interest in acting before his father’s death in 1973. The younger Lee made his acting debut in the television sequel to the Kung Fu TV series in 1986, and soon after moved to major studio action films. His casting in The Crow was considered big entertainment news at the time.

On March 31, 1993, with three days left to film, Lee was killed in an on-set accident. Ironically, this occurred during the scene in which his character is killed prior to his supernatural resurrection. Lee died after being shot with an improperly prepared prop gun; the revolver still had a dummy bullet lodged in the chamber, and the discharge of the loaded blank provided enough force to fire as if it were a live round. Lee was struck in the stomach and died after six hours of surgery.

In another unfortunate coincidence, Lee had been engaged to be married to Eliza Hutton, who also worked in the film industry, the week after completing the film. Hutton, along with Lee’s mother, Linda Lee Cadwell, supported director Proyas in his effort to complete the movie. Using a combination of stand-ins and nascent digital effects, Proyas completed scenes and edited the film in way to make the process seamless.

Lee’s tragic death drew wider attention to the film and propelled interest in it. The studio Dimension Films, which at the time was the genre label within Miramax, marketed it aggressively. The movie would open at #1 at the box office in the United States while receiving solid reviews. While the atmosphere, action, and music were widely praised, a number of critics offered raves about Lee himself. In particular, Roger Ebert wrote, “It is a sad irony that this film is not only the best thing he accomplished, but is actually more of a screen achievement than any of the films of his father, Bruce Lee.”

3. Alex Proyas Brought the Style

The recently resurrected Eric’s memories of Shelly drive him to revenge; the music is “Burn” by The Cure. (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips)

The pages of O’Barr’s comic are steeped in Gothic style. The black and white book relies heavily on the shadows and sharp angles of German horror films and film noir. The striking look of the lead character’s make-up (which leads one film character to refer to him as “a mime from hell”) is amplified by lyrical passages from bands like Joy Division and The Cure that O’Barr quotes throughout. The visual achievement that director Alex Proyas essays is a very direct transposition of this atmosphere from the page to screen. The Crow was only the director’s second feature; his first film, Spirits of the Air, Gremlins of the Clouds had been nominated for two AFI Awards and took the Special Prize at Yubari International Fantastic Film Festival in Japan.

In The Crow, Proyas not only echoed the look of the comic, but also employed other innovations. He occasionally used distorted lensing to capture scenes from the point of view of the titular bird. Proyas also used unusual lighting, such as one scene in a bathroom that’s illuminated only by the lights over the mirror; those choices play into the dark-and-shadow visual aesthetic of the original while doing something different with the scene. The action and music-performance scenes remain top-notch as well.

4. The Music Mattered

“Time Baby III” by Medicine (Uploaded to YouTube by Medicine / Atlantic Records)

The mid-90s saw seismic shifts in music. Among the most important movements was the ascent of alternative rock, fueled in part by the breakthrough of the Seattle bands like Nirvana and Pearl Jam in 1991. The overall style played to alienated youth, which was exactly the kind of audience that had found the original comic. By 1994, dozens of these new acts (like Nine Inch Nails and Stone Temple Pilots) had made deep impressions, while pioneering older acts like The Cure and Joy Division were being rediscovered. O’Barr’s own taste in music lined up with this new soundscape, and Proyas recognized that. The soundtrack of the film brought in a number of of-the-moment acts and veterans, including The Cure themselves. Nine Inch Nails covered “Dead Souls” by Joy Division, which was referenced in the original comic. Other acts included Pantera, Stone Temple Pilots, the Jesus and Mary Chain, Rage Against the Machine, Violent Femmes, and Jane Siberry. Medicine and My Life with the Thrill Kill Kult both appear in the film, performing their songs from the soundtrack.

The 14-song album hit #1 on the Billboard album chart, selling nearly four million copies. The Stone Temple Pilots song “Big Empty” was released off of the soundtrack as a single; it hit the top ten of both the Mainstream and Modern Rock charts. A second album, featuring the instrumental score written by celebrated composer Graeme Revell, was released; it includes “Inferno,” the rooftop guitar solo played by Lee’s character in the movie.

5. It Was Good

Trailer for The Crow (Uploaded to YouTube by YouTube Movies

There’s a lot to be said for simply making a good movie. The Crow combined a solid roster of talent in terms of the cast (not just Lee, but veteran actors like Ernie Hudson, Michael Wincott, David Patrick Kelly, and Tony Todd, plus an affecting child-actor turn from Rochelle Davis). The director, the musicians behind the soundtrack, and a talented crew, notably in sound, lighting, and stunt work produced great material. The film arrived at precisely the right time, with the music fitting the times. Tim Burton’s darker comic-book work helped paved the way with two prior Batman features in 1989 and 1992. Lee’s death, as well as the then-recent death of Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain weeks before the film’s release, cast long shadows that played into the melancholy in the air and in the film. Dimension also showed savvy in the marketing of the movie, making large ad buys on MTV and prominently featuring the music in the ads. The film still carries an 81% positive critic score and 90% audience score at review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, with strong notices coming from outlets like The New Yorker, Variety, and the L.A. Times. TV Guide offered rapturous praise, calling the film “A gorgeous black valentine that captures the essence of adolescent misery, coupled with a wildly romantic vision of the power of pure love to overcome all obstacles — even the grave.” Rolling Stone critic Peter Travers was wowed by Lee, writing “Draven is the rocker as avenging angel, prowling the streets cracking jokes and heads but also capable of expressing great feeling. Lee is sensational on all counts in a final performance that brims over with athleticism and ardor.”

Today, James O’Barr continues to create The Crow in comics, with the most recent series published last year. Three additional Crow films were made in 1996, 2000, and 2005, bracketing a 1998 television series. Director Colin Hardy and actor Jason Momoa were said to be involved in a new film, but both departed the project in 2018. There have also been novels, card games, and a video game. Still, the most iconic version of the character outside the written page continues to be the one brought to (after)life by Brandon Lee. The Crow remains a unique snapshot of its time, creating an effective parable about love and loss. The work deals in some serious darkness, but as Lee’s character himself says, “It can’t rain all the time.”

Higher, Further, Faster: 5 Things You Need to Know about Captain Marvel

The first female-led film from Marvel Studios, Captain Marvel, starring Brie Larson, opens in wide release just in time for International Women’s Day. It’s an appropriate date, given both the tone and history of the character Carol Danvers. With over 50 years of comics behind her, she’s been a journalist, a fighter pilot, an Avenger, and more. As the certain box office hit opens, we look back at five things you should know about the Captain, and why she’s not the only hero to bear the name.

1. Wasn’t the Shazam! guy called Captain Marvel?

It’s a source of a lot of confusion in both fandom and mainstream circles, but yes, there have been a few Captain Marvels at different companies. The most obscure (and goofiest) was a character from M.F. Enterprises that appeared in a comic series in the mid-1960s. This Captain Marvel was an alien robot that could detach his limbs. However, the character only appeared in a handful of issues before receiving a career-ending legal smackdown during a case that involved both Marvel Comics and DC Comics.

The “Shazam!” Captain Marvel debuted in 1939 in Whiz Comics #2 from Fawcett Comics (the cover date says 1940, but it hit stores a bit earlier). Created by Bill Parker and C.C. Beck, young Billy Batson was chosen by the wizard Shazam to receive super-powers (and an adult body) when he said the wizard’s name. The utterance gave him the wisdom of Solomon, the strength of Hercules, the stamina of Atlas, the power of Zeus, the courage of Achilles, and the speed of Mercury. Billy adopted the name Captain Marvel for his adventuring. In the 1940s, sales of the character rivaled, and occasionally surpassed, those of Superman. Unfortunately for Fawcett, National (as DC was known at that time) took umbrage to the similarities between the good Captain and Superman, and sued in 1941. The legal challenges went on for years through multiple trials and iterations before Fawcett settled for $400,000 and stopped publishing Captain Marvel titles by 1954.

In 1967, Marvel decided to publish their own book called Captain Marvel, starring an alien superhero (more on him in a minute). They registered the trademark. When DC licensed the Shazam! characters from Fawcett for a revival in the 1970s, Marvel challenged them over the use of the title. Since that time, all of DC’s books featuring the character have used the Shazam title due to Marvel’s copyright. Since the 2000s, the character itself is now called Shazam in the comics, and shall be in April’s Shazam! film as well.

2. So who are the Captain Marvels of Marvel Comics?

The first Marvel Comics Captain Marvel was, wait for it, Captain Mar-Vell. Created by Stan Lee and artist Gene Colan, Mar-Vell debuted in Marvel Super-Heroes #12 in 1967. A human-looking alien from the Kree Empire, Mar-Vell is sent to Earth to spy on our planet’s developing space program. Mar-Vell eventually turns against his masters and fights to protect the planet under his new heroic identity. He would become an ally and member of the Avengers.

Originally introduced as a love interest for Mar-Vell by Colan and writer Roy Thomas, Carol Danvers first appeared in Marvel Super-Heroes #13. An Air Force officer, Danvers is handling security at a base and meets Dr. Walter Lawson (Mar-Vell’s newly adopted secret identity). A few issues later, Danvers is caught in an explosion caused by an alien device. Since this is Marvel Comics, accidents with radiation and alien devices invariably give you super-powers.

When Carol Danvers showed up again, it was to headline the new comic Ms. Marvel in 1977. As the titular hero, Danvers had gained super-strength, speed, and the power of flight. The “Ms.” served as a hat-tip to Gloria Steinem; in fact, Danvers would soon be running a magazine and demanding equal pay for her work. She too joined the Avengers and was a mainstay of that comic for several years, even after hers was cancelled in 1979 with issue #23. After some unfortunate writing and editorial decisions removed Danvers from the Avengers title, popular X-Men writer Chris Claremont (who had also written issues of Ms. Marvel) stepped in and brought Danvers to his stable of books in 1982. He gave her a power-up and the new name Binary and sent her off into space with Marvel’s space pirate characters, the Starjammers.

With Ms. Marvel in space and Mar-Vell gone (the character died of cancer in a 1982 special), the name Captain Marvel was available. Writer Roger Stern and artist John Romita Jr. created a new Captain Marvel for The Amazing Spider-Man Annual #16 in 1982. The fact that the new Captain was a black woman, New Orleans harbor patrol officer Monica Rambeau, generated a lot of positive publicity and some mild shock in some fan circles. The energy-powered Rambeau became popular quickly, joining (surprise!) the Avengers and even landing the cover of Marvel’s first role-playing game in 1984. Rambeau ran with the Captain Marvel name until 1996, when she ceded it to Mar-Vell’s son Genis and took the identity of Photon. Rambeau has since had a few different code names; today she’s called Spectrum. During this time, Carol returned to Earth, rejoined the Avengers, and used the name Warbird before becoming Ms. Marvel again.

As for Genis-Vell (created by Ron Marz and Ron Lim), he’s one of three children of Mar-Vell (dude got around). Both Genis and Mar-Vell’s daughter, Phyla, have used the Captain Marvel name over time. Genis headlined a couple of solo series, joined the Thunderbolts, and eventually allowed himself to be destroyed when his powers got out of control and threatened the universe. Phyla-Vell (created by Peter David and Paul Azaceta) would likewise run through a few code names, but her adventures have primarily been showcased alongside the team that she joined, the Guardians of the Galaxy. Mar-Vell’s third child is Teddy Altman, aka Hulkling. The son of Mar-Vell and a Skrull princess, Teddy uses his shape-shifting and strength powers as a member of the Young Avengers, usually preferring an appearance resembling a teen Hulk.

For a brief period, Kree hero Noh-Varr, known as Marvel Boy, was persuaded by villain Norman Osborn to join his so-called Dark Avengers as a new Captain Marvel. Noh-Varr used the name for only a brief time. He soon abandoned Osborn for a role with both the main Avengers team, where he went by the name Protector, and the Young Avengers.

In 2012, Carol finally took the name Captain Marvel and got a new first issue. Written by Kelly Sue DeConnick with art by Dexter Soy, this comic launched the stories that serve as the basis for the character that will be seen in the new film. Danvers maintains membership in the Avengers, but she also leads Alpha Flight, Earth’s space-based first line of defense against alien threats.

3. Speaking of alien threats, who are the Kree and the Skrulls?

The Kree Empire is a conglomeration of worlds run by the Supreme Intelligence. An amalgam of all the great Kree minds stretching back centuries, the Intelligence is seen in comics as a giant green head. In the film, it will be seen as a regular-sized Annette Bening. Kree look like humans, though a number of them have blue skin tones. They frequently represent themselves as having good intentions, but that’s not always the case. Their search for genetic purity resulted in the creation of the Inhumans characters, and other machinations have put them in conflict with the heroes of Marvel Comics many times.

The Skrulls are the sworn enemies of the Kree. Distinguished by green skin, wrinkly chins, and pointy ears, the Skrulls use their shape-shifting abilities to spy and sow chaos. First encountered by the Fantastic Four in their second issue, the Skrulls have bedeviled the Marvel Universe for years, notably during the Secret Invasion story of the 2000s, when they kidnapped and replaced a number of heroes.

The biggest Kree/Skrull story is the “Kree-Skrull War,” which took place over the course of nine issues of The Avengers between 1971 and 1972; it was written by Roy Thomas with art by Neal Adams, Sal Buscema, and John Buscema. It’s been reported that some elements of this story surface in the Captain Marvel film.

4. What makes Captain Marvel important as a character?

Carol Danvers has been breaking stereotypes about female comic book characters for over 50 years. Her military background, ever-increasing power-set, and take-charge demeanor set her apart. The character has been depicted as having to overcome obstacles like sexism, but also personal demons like alcoholism and a rough childhood. She doesn’t always make the right decisions, and her strong will occasionally places her at odds with other heroes.

Nevertheless, she fights from a place of good intentions and maintains a number of strong friendships with other female heroes like Spider-Woman (Jessica Drew) and Rambeau. Her romantic life is often a mess, but that has never been a defining characteristic. Her prominent role in the Marvel Universe is shown to have inspired other heroes. Muslim teen Kamala Khan (created by writer G. Willow Wilson, editors Sana Amanat and Stephen Wacker, and artists Adrian Alphona and Jamie McKelvie) became the new Ms. Marvel in 2014 as a tribute to Danvers.

In the films, Captain Marvel’s solo movie sets us up for the character’s entry in Avengers: Endgame in April. That film, the 22nd entry in Marvel’s Cinematic Universe, wraps up the original three “phases” of the MCU that began with Iron Man in 2008. Marvel Studios president Kevin Feige has noted more than once that Captain Marvel will be one of the central characters of the MCU as the post-Endgame slate of films proceeds.

5. That’s all great, but what about Goose the cat?

The first trailer for Captain Marvel (Uploaded to YouTube by Marvel Entertainment)

In the comics, Captain Marvel’s cat is named Chewie, after Chewbacca from the Star Wars saga. They renamed Chewie “Goose” in the film as a tribute to Tom “Maverick” Cruise’s Radio Intercept Officer sidekick played by Anthony Edwards in Top Gun. As for Goose’s overall importance . . . let’s just say she’s probably a little bit more than she initially appears to be.

Feature image: Shutterstock

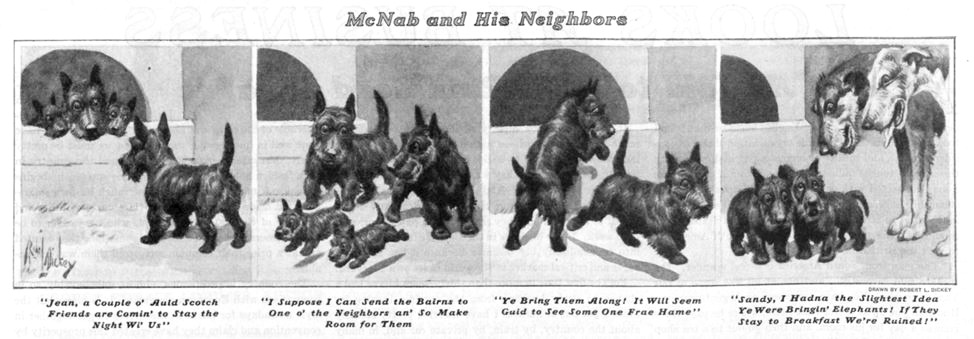

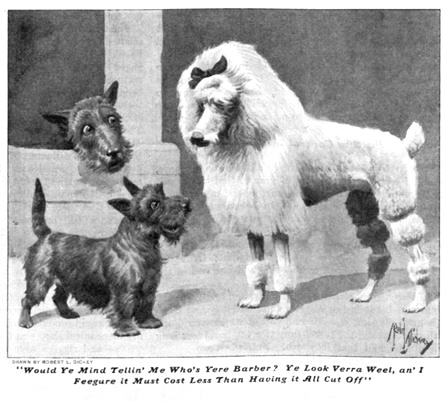

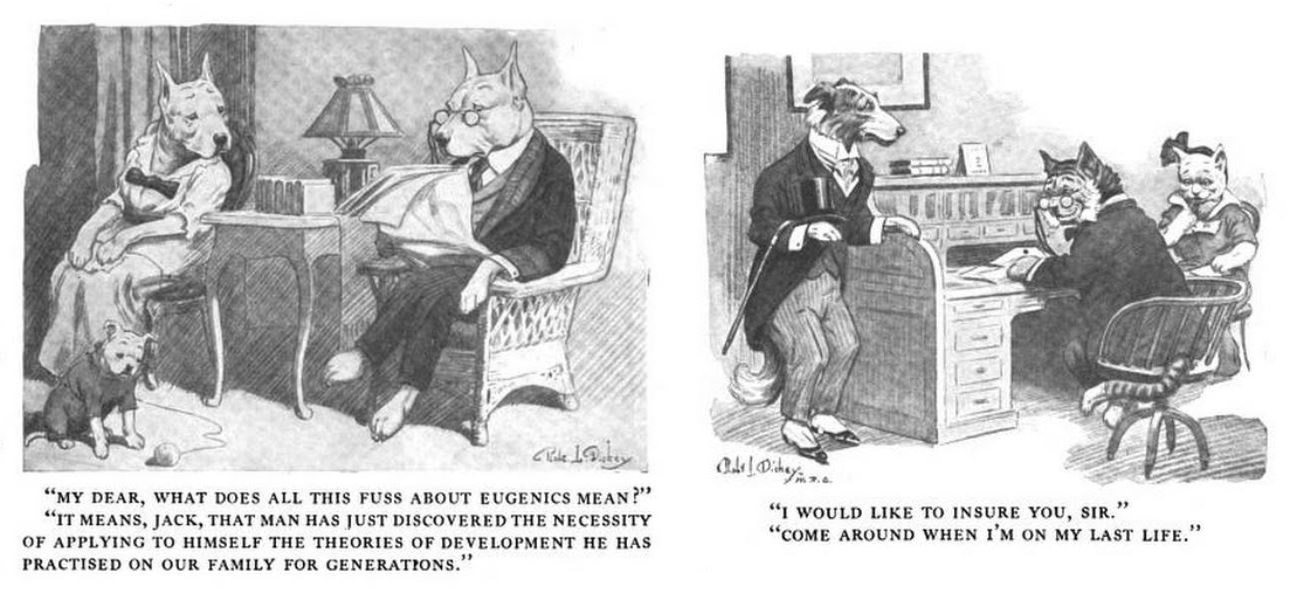

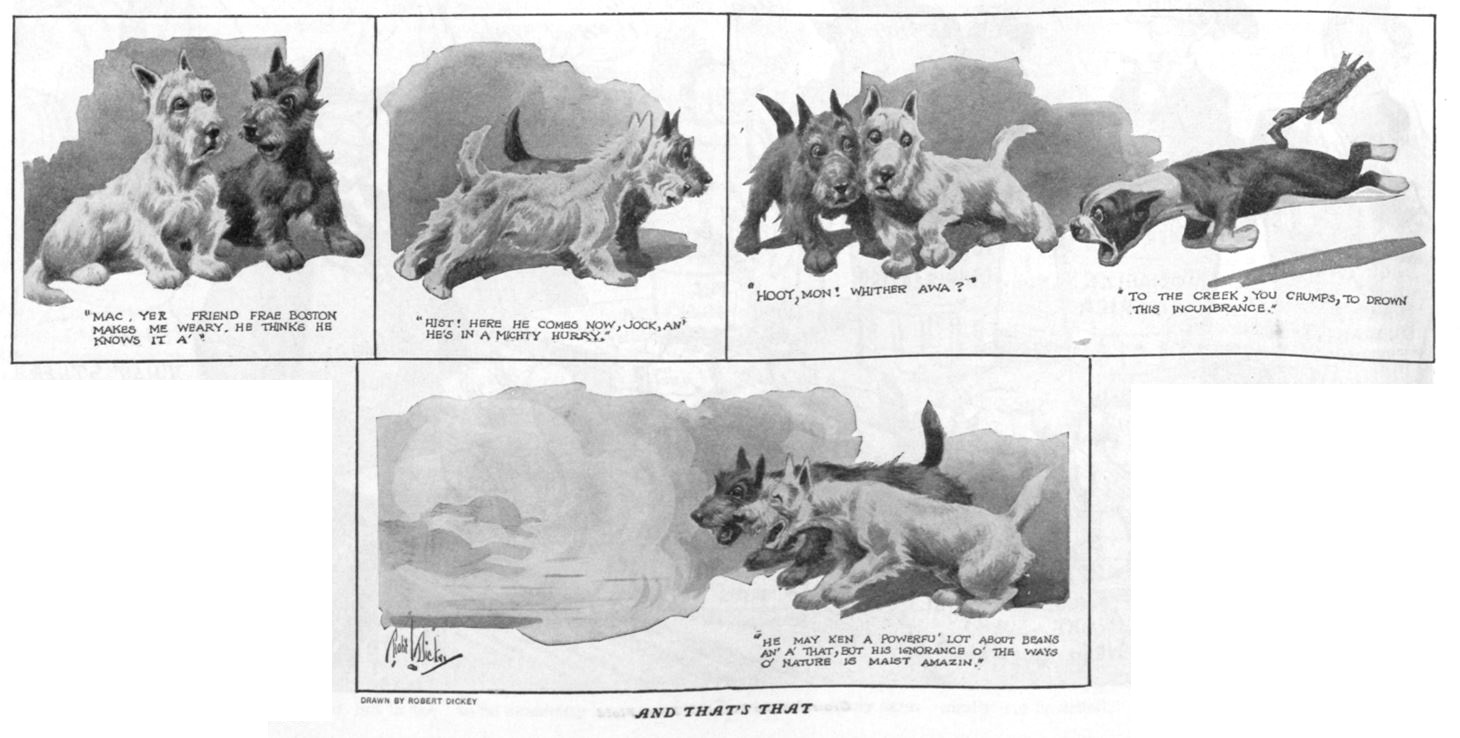

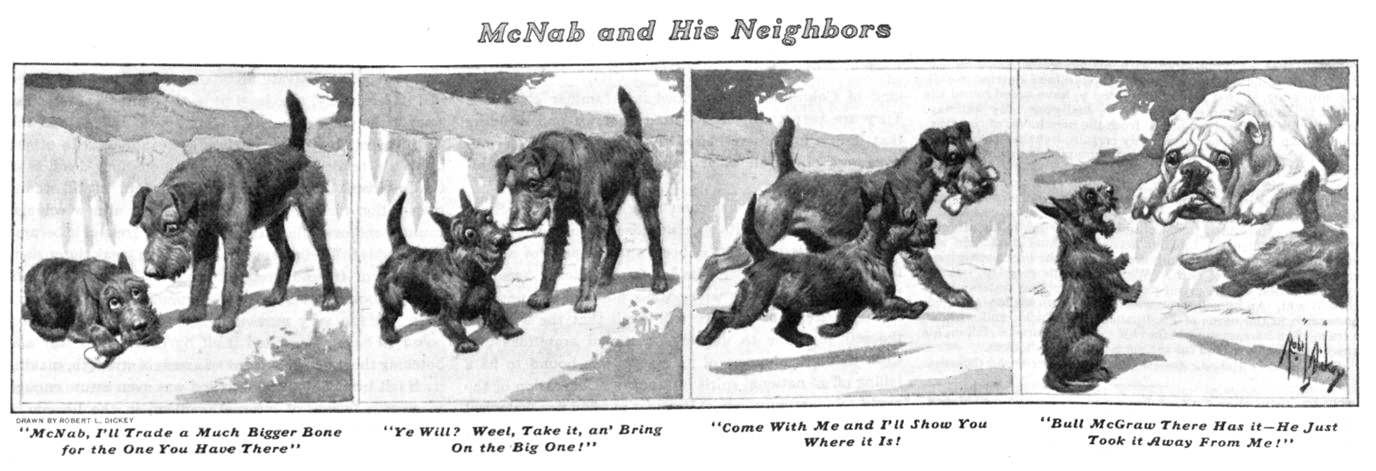

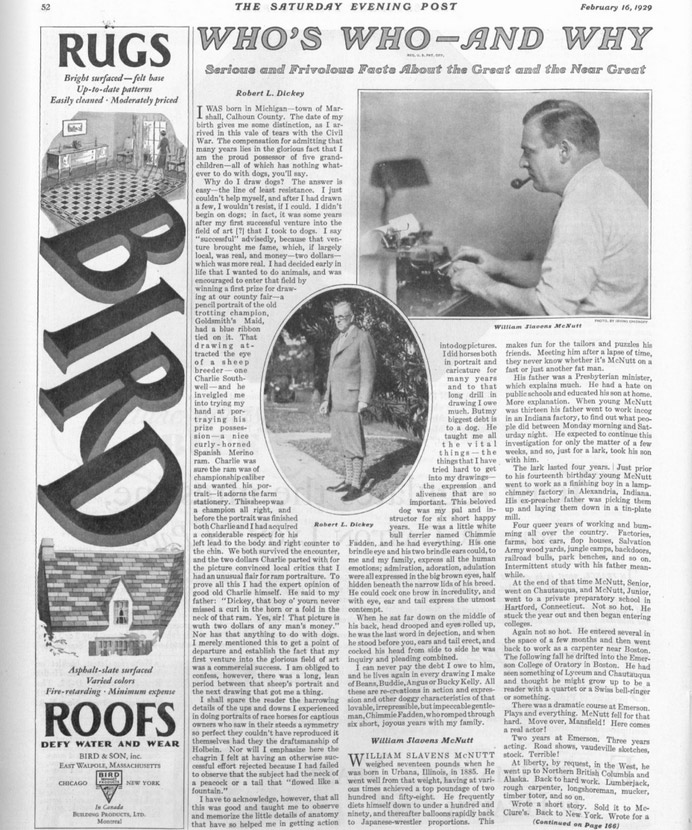

The Bizarre and Adorable Canine Comics of Robert L. Dickey

A Midwesterner through and through, Robert L. Dickey displayed a peculiar commitment to thick Scottish dialect in portraying his characters Sandy and Jean McNab. The McNabs were a spousal pair of Scottish Terriers in Dickey’s comic strip, “McNab and His Neighbors” that ran in this magazine through the 1920s. Whether the McNabs were beloved because of their innate cuteness or the silliness of lines of dialogue that would nowadays have readers running for a translator app (“It will seem guid to see some one frae home”) is difficult to say. But Dickey — in spite of his decades of animal illustration that may have changed the way we see our pets — has been all but forgotten. The once-celebrated artist has nary a Wikipedia page or accessible obituary.

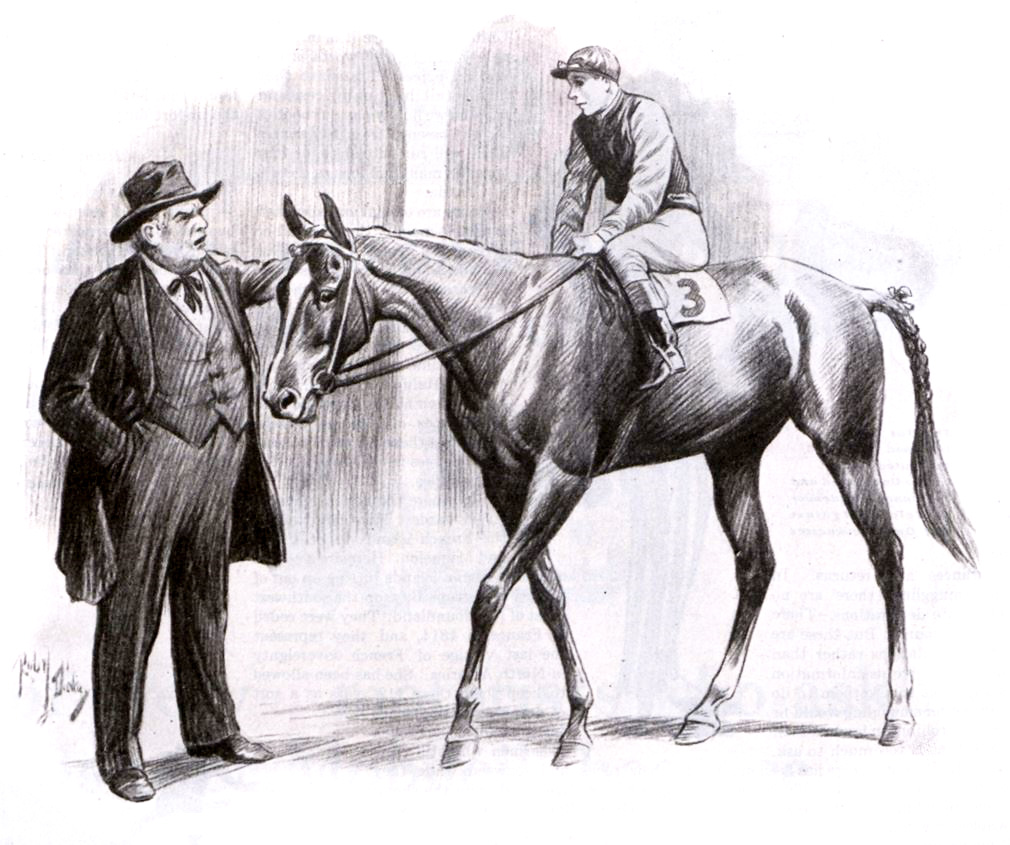

Before drawing adorable pooches, Dickey made his name as a horse illustrator for Chicago’s The Horse Review. As a child, he was enamored with animals, and at a young age he won first prize at the county fair for a drawing of Goldsmith Maid, a legendary mare of harness racing in the 19th century. His winnings amounted to one dollar and a ribbon, but he soon found himself taking commissions from race horse owners and local farmers from his hometown of Marshall, Michigan.

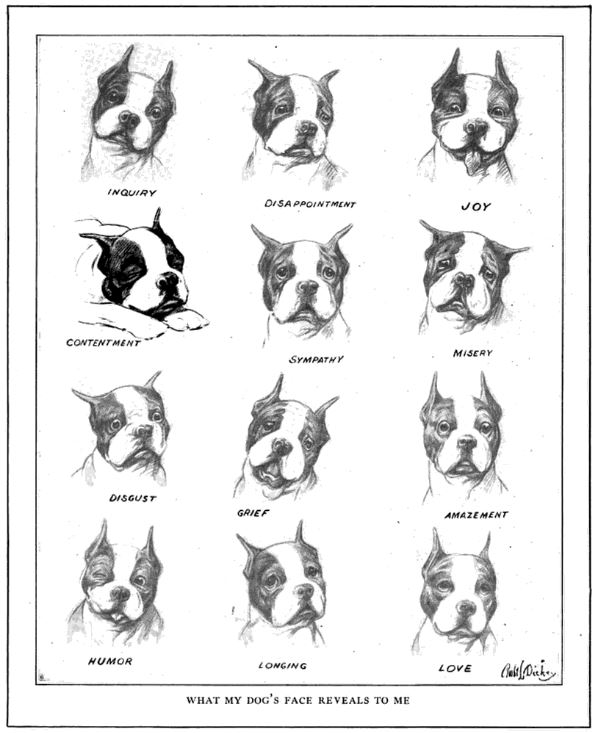

Though he sustained an enthusiasm for horse racing, Dickey’s true artistic muse became the canine. One specific canine, in fact: a white bull terrier named Chimmie Fadden. In the pages of this magazine, in 1929, Dickey proclaimed that his former pet had been a most important art teacher: “His one brindle eye and his two brindle ears could, to me and my family, express all the human emotions; admiration, adoration, adulation were all expressed in the big brown eyes, half hidden beneath the narrow lids of his breed. He could cock one brow in incredulity, and with eye, ear and tail express the utmost contempt.” Of his beloved Chimmie, Dickey also said, “He taught me all the vital things — the things that I have tried hard to get into my drawings — the expression and aliveness that are so important.”

Dickey moved to New York and began publishing comics and illustrations with Life, at the encouragement of editors John Ames Mitchell and Thomas L. Masson. In Dogs from “Life” (1920), Masson calls Dickey “perhaps the best dog artist in this country,” and he credits that success to Life’s guidance, of course. Masson writes that Mitchell advised Dickey to give his dog illustrations more realistic qualities instead of making caricatures: “Don’t make your dogs humorous. You are too good an artist to attempt that sort of thing. Make your dogs true to life — just as they are.”

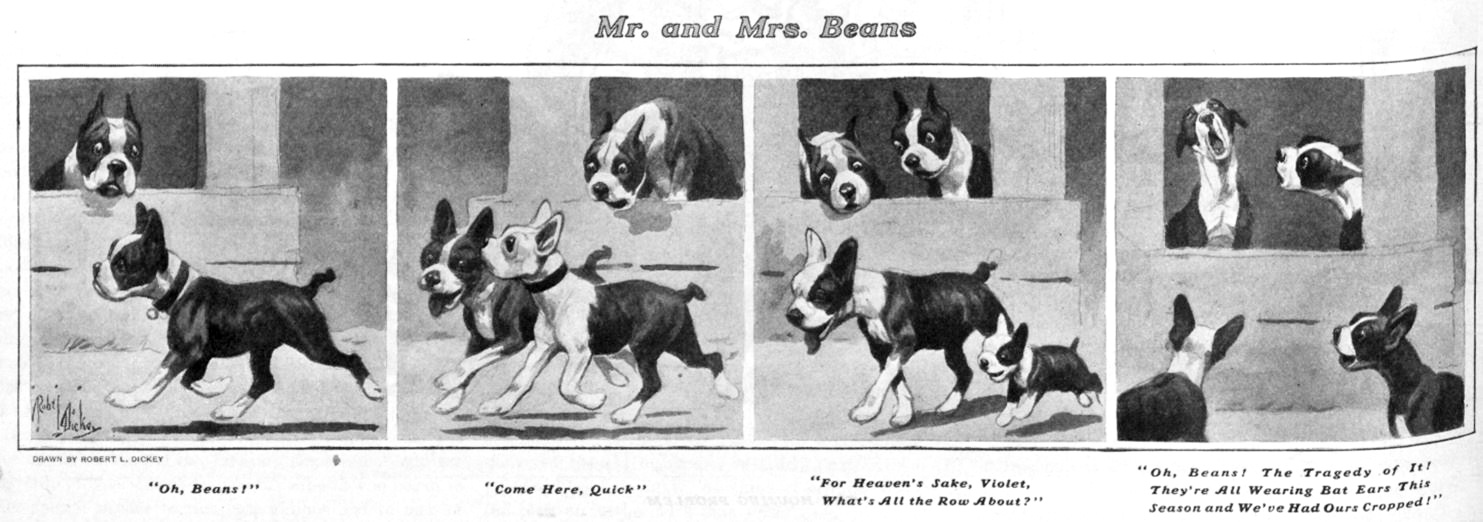

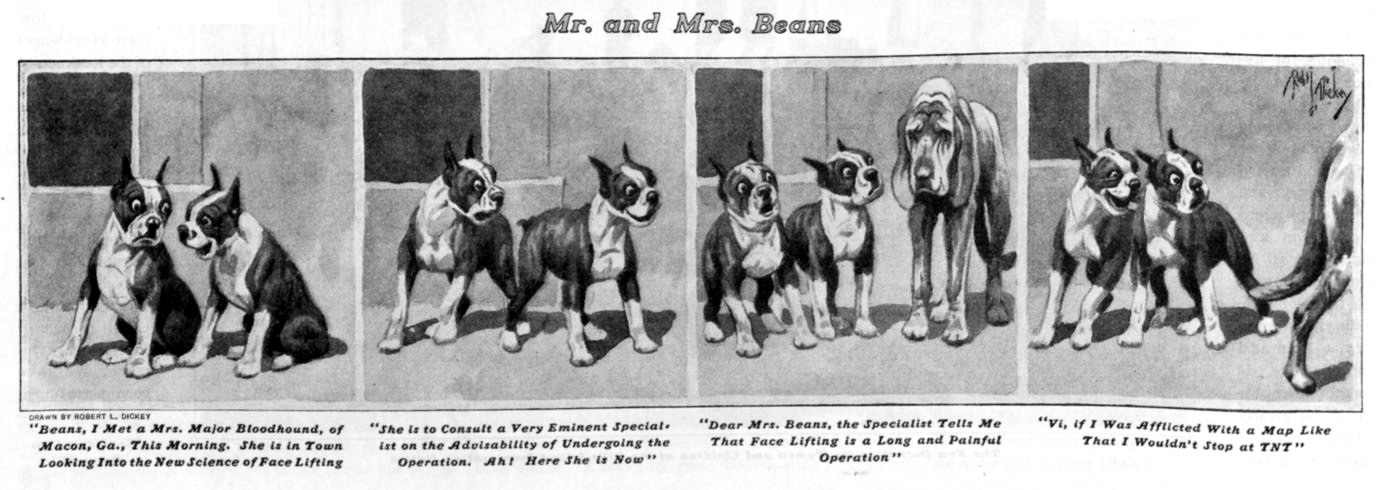

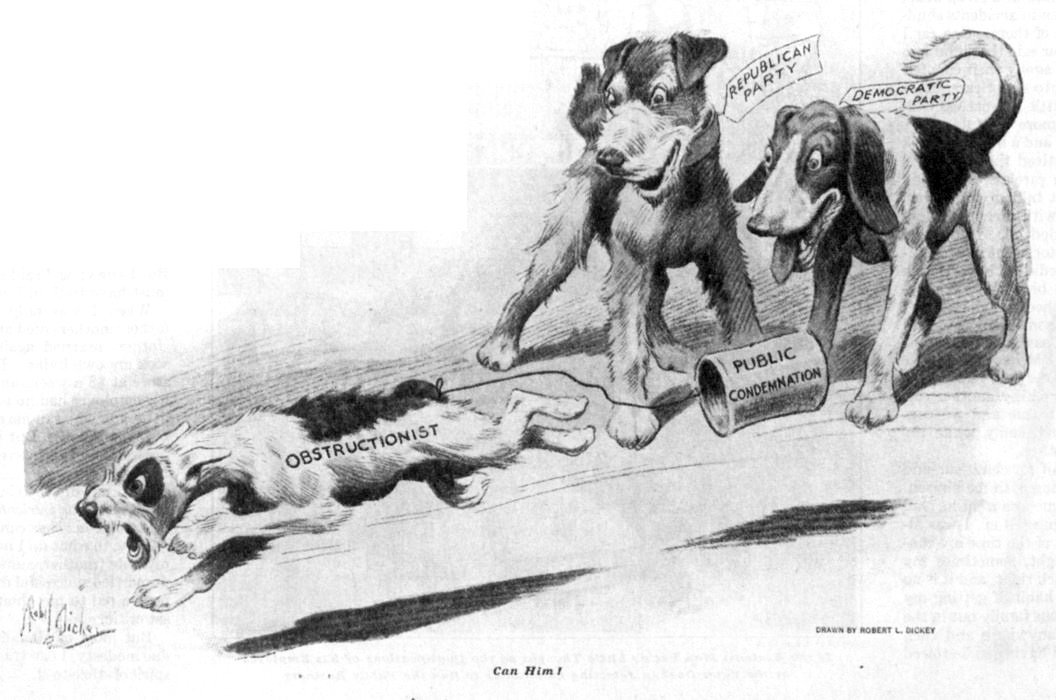

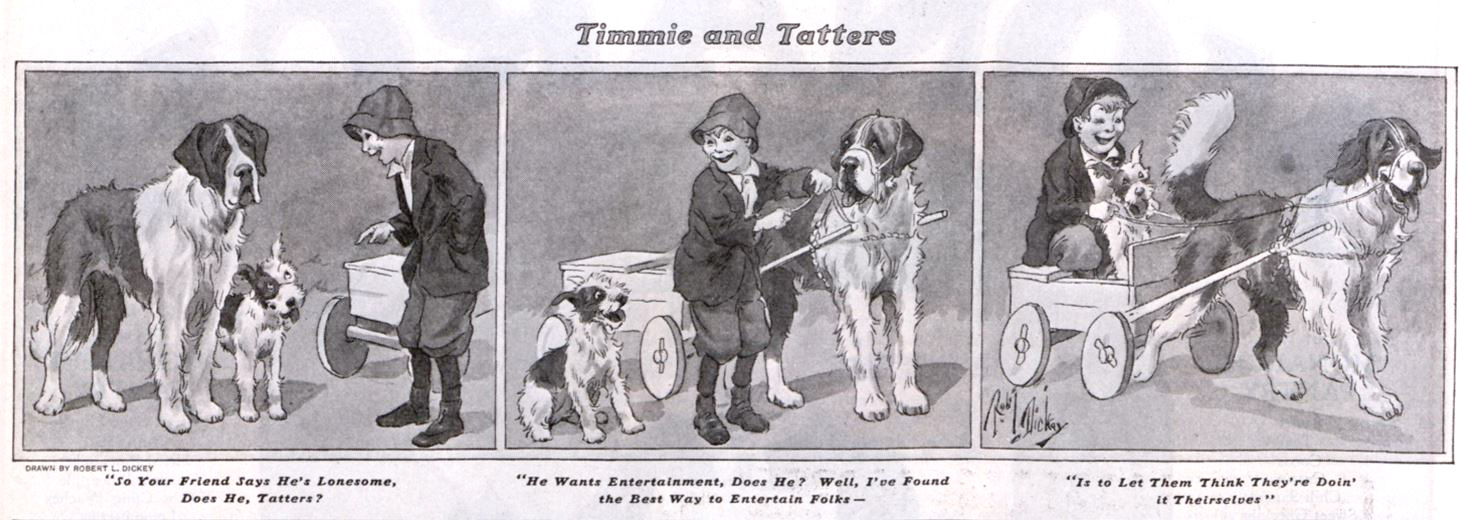

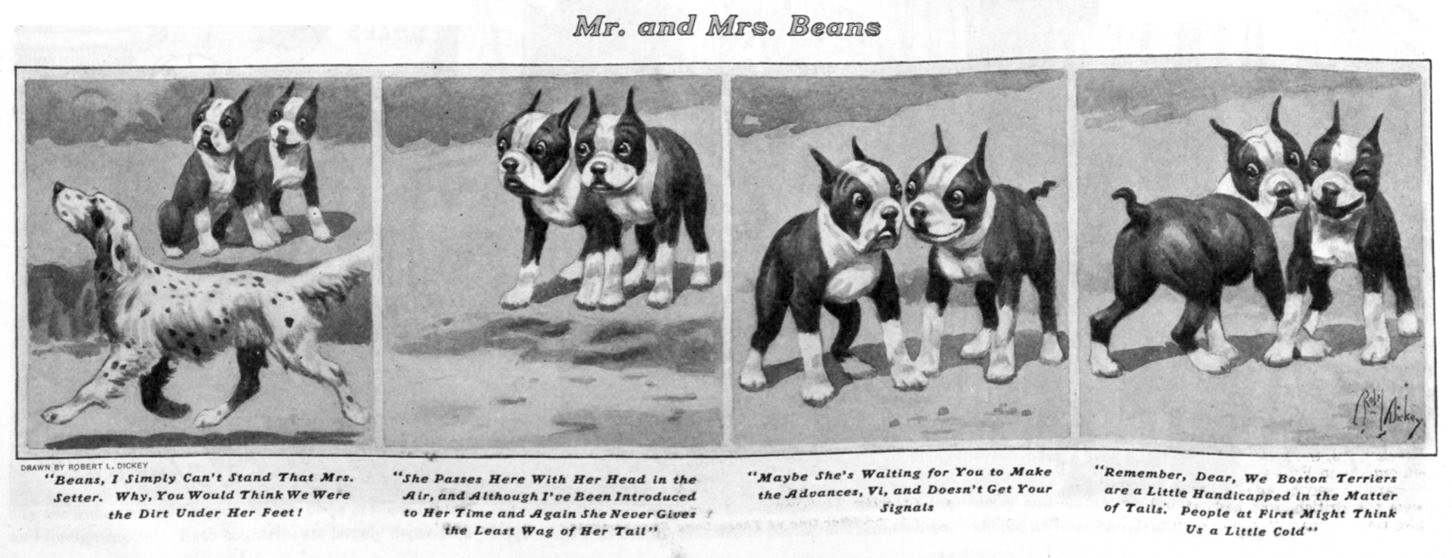

If Dickey followed the Life editor’s advice, he promptly disregarded it for his work in The Saturday Evening Post. After a few tries at political cartoons, Dickey settled in with some recurring characters for the “Short Turns and Encores” section. Throughout the ’20s, in strips like “Timmie and Tatters,” “McNab and His Neighbors,” and “Mr. and Mrs. Beans,” Dickey portrayed cute dogs of various breeds with the humorous hangups and eccentricities of everyday people. With an affinity for terriers, Dickey’s strips showed the lighter side of relationships, middle-class vanity, and machismo.

Beans and Violet, Dickey’s signature Boston Terriers in “Mr. and Mrs. Beans,” were named after his own Boston Terriers that travelled with the artist any time he left New York City. Dog historian Cathy Flamholtz credits Dickey for the immense popularity of the breed in the 1920s and ’30s (in Boston Terriers: The Early Years), writing, “While the critics may have scoffed at Robert Dickey’s drawings, the public loved them! Confirmed readers of the most popular magazines fell in love with the clownish dogs seen in the pages of their favorite publications. They wanted one of these dogs and they bought ‘America’s Dog’ in large numbers. Soon, Boston Terriers were one of the most popular breeds in the country.” Flamholtz notes of Dickey’s work in comic strips, tobacco ads, and magazine covers, “The drawings reflect the charm, curiosity, mischievousness, and intelligence of the Boston Terrier. They could only have been made by someone who knew the breed so intimately.”

In spite of Dickey’s contributions to American illustration, he is scarcely remembered. His crowd-pleasing comics filled with “puppy dog eyes” and deviant hounds changed the way dogs were rendered in publication and likely altered the way people thought about their four-legged friends. His strips were printed in newspapers around the country as well as Ladies’ Home Journal, Century, and other magazines. He also illustrated the Barse edition of Black Beauty and books like Lad: A Dog and A Dog Named Chips by Albert Payson Terhune. But in his characters, Beans, Violet, and Sandy McNab, Dickey opened the door in the public imagination to the possibility of a dog expressing human faults, joys, and sorrows — and maybe even sporting a Scottish accent.

Order a copy of The Saturday Evening Post: A Celebration of Dogs!, with full-color images by Robert L. Dickey, Norman Rockwell, and more.

Order a copy of The Saturday Evening Post: A Celebration of Dogs!, with full-color images by Robert L. Dickey, Norman Rockwell, and more. 10 Comics You Should Read Right Now

Read our article, Be Heroic! It’s International Read Comics in Public Day!

Comics aren’t just for ten-year-old boys anymore. Which comics should you be reading? There are thousands of series to choose from, so where’s a beginner to start?

That’s where I come in. I’m the resident comic book guy, and that’s because I’ve lived the entire cycle from fan to comics journalist to published pro comic book writer. This isn’t an exhaustive list by the stretch of anyone’s imagination, but it might provide some hints of where you might like to start. I don’t list every creative contributor to every volume mentioned, but that in no way diminishes the contributions of the writers, artists, letterers, colorists, and editors that work hard every day to entertain their readers.

1. If You Like Marvel Movies

You might have 10 years of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, but you’ve got about 79 years of Marvel comics. A few gems that might pique the interest of the Marvel moviegoer include Captain America: The Winter Soldier by Ed Brubaker and Steve Epting, the Hawkeye solo series by Matt Fraction and David Aja, any Thor book written by Jason Aaron, the various volumes of Guardians of the Galaxy written by Dan Abnett and Andy Lanning, Black Panther: A Nation Under Our Feet by Ta-Nehisi Coates and Brian Stelfreeze, and the original Infinity Gauntlet by Jim Starlin, George Perez, and Ron Lim.

2. If You Like the Justice League

So you grew up with the Super Friends or Justice League on TV and you love the Big Guns of the DC Universe. You’re in luck: You have some of the most acclaimed comics ever ahead of you. Check out 1986’s The Dark Knight Returns by Frank Miller and Klaus Janson, which set the stage for the Batman of the movies. Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely’s All-Star Superman captures the essence of the Man of Steel. The various volumes of Wonder Woman by George Perez give you some classic Diana stories. And Grant Morrison’s masterful run on JLA with Howard Porter and others redefined the group for the modern audience.

3. If You Like Biographies/Autobiographies

Comics are not just super-heroes. Super-heroes are the “cop show” of comics; there are a lot of them out in there in a lot of flavors, but they aren’t the only thing to watch. In fact, a number of incredible biographies exist in comic form. One of those is The Fifth Beatle: The Brian Epstein Story by Vivek J. Tiwary, Andrew C. Robinson, and Kyle Baker; it tells the story of the Fab Four’s visionary but doomed manager. A towering achievement in comics bio (and autobio) is Top Shelf’s March trilogy by John Lewis, Andrew Aydin and Nate Powell. The John Lewis in question is indeed the legendary congressman that fought for civil rights, and his story is rendered wonderfully by the sublime art of Powell. One more I can’t pass up is Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic by Alison Bechdel (also known as creator of the Bechdel test). With unflinching honesty, Bechdel deals with family secrets, including her own. And there’s also Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis and Craig Thompson’s Blankets and Art Spiegelman’s Maus . . . okay, time to move on.

4. If You Like The Lord Of The Rings, But Wish It Were Funnier

Believe me, there’s a metric ton of awesome fantasy comics out there, but I keep coming back to Bone. Jeff Smith’s magnum opus is available in one complete volume. In it, three cousins that look like funny comic strip characters stumble in a high fantasy valley on the verge of war. Becoming embroiled in events both hilarious (The Great Cow Race) and terrifying (the Lord of the Locusts may haunt your dreams), the cousins try to help their new friends while searching for a way back home. A sheer delight from cover to cover, Bone has won 10 Eisner Awards and is beloved around the world. Don’t miss it.

5. If You Like Teenage Heroes

While there’s no shortage of teen heroes in comics, I’m going to focus a little bit on the Big Two of Marvel and DC. In recent years, Marvel’s had a bit of a teen hero renaissance with G. Willow Wilson’s Ms. Marvel at the forefront. Ms. Marvel is Kamala Khan, a Muslim Pakistani-American teen with shapeshifting powers and an encyclopedic knowledge of super-heroes. Though only introduced five years ago, Kamala has made her way into animation, action figures, and the comic book ranks of The Avengers. She’s also a member of teen team The Champions, which gathers a number of Marvel’s youth movement in one book. Kamala also shares the Marvel Rising animated series with The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl, a ridiculous-heroine with a thoroughly hilarious series (for you Netflix fans, she’s Luke Cage and Jessica Jones’s babysitter).

On the DC side, the terrific Super Sons books follow Superboy (Jonathan Kent, son of Clark and Lois) and Robin (Damian Wayne, son of Bruce and his enemy Talia ah Ghul). As written by Peter J. Tomasi, every issue contains at least one laugh-out-loud moment centering on the grudging friendship between the relentlessly upbeat Superboy and the comically dour Robin. Robin is also featured in DC’s young hero hang-out, Teen Titans.

6. If You Like Mysteries

There are enough mystery series and original graph novels in comics for lit sites to run features on the top 10, or 25, or 50 mystery comics. I’ll hat-tip three. Torso, published at Image Comics by Brian Michael Bendis and Mark Andreyko, is a fictionalized account of the true story of the hunt of the Cleveland Torso Murderer of the 1930s by legendary lawman Eliot Ness. Batman: The Long Halloween by Jeph Loeb and Tim Sale gives us an early case from Batman’s career as he hunts a holiday-themed serial killer for a calendar year. The last one, My Favorite Thing is Monsters, published by Fantagraphics, has a story behind it that’s almost more remarkable than the book itself. After suffering from paralysis brought on by West Nile virus, writer and artist Emil Ferris fought her way back to recovery while working on her 700-page mystery. It won three Eisner Awards last year and is widely considered the best graphic novel of 2017.

7. If You Like Shakespeare, Gothic Culture, and General Amazement:

The Sandman series, by writer Neil Gaiman and a murderer’s row of incredibly talents artists, remains one of the great achievements in comics. After a period of captivity, Morpheus, the king of dreams, tries to reunite with his fractured family, including his loveable sister Death. A high point in fantasy, the series defied conventions and came to stand for “literary comics” in the best possible sense. Gaiman, of course, has continued to produce stellar works in comics, prose, and other media (American Gods, anyone?).

8. If You’re Anywhere from K-12

If you don’t know Raina Telgemeier, your kids or grandkids do. A one-woman brand that means great, heartfelt comics, Telgemeier built up a solid resume of work before breaking out with the autobiographical Smile in 2010; it stayed on The New York Times bestseller list for more than 220 weeks. Each subsequent release (Drama, Sisters, and Ghosts) has only expanded her popularity and demonstrated her unique sensitivity to the real issues affecting young people. To borrow another publishing phrase, she’s a wonder.

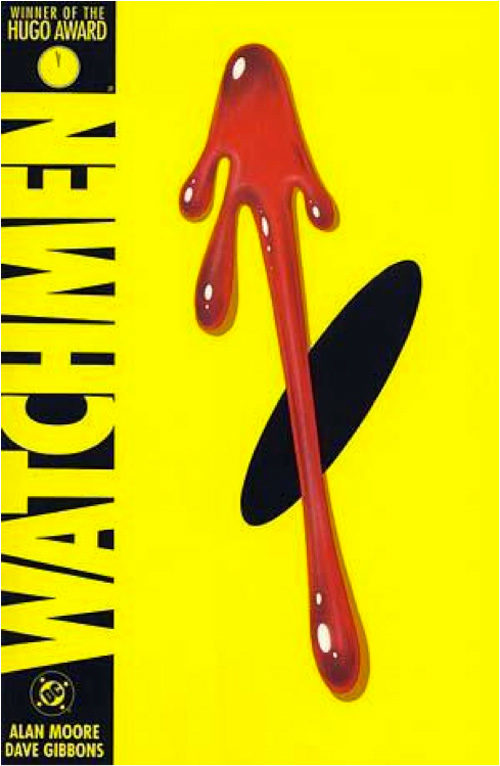

9. If You Like It Deconstructed

Alan Moore got big in super-hero comics, then he wanted to burn it all down. Seen by many as the author laureate of the comics form, Moore rebuilt DC’s Swamp Thing into a work of post-modern horror before turning his attention to the entire super-hero genre. Watchmen, with Dave Gibbons, remains a perennial bestseller and one of the things that pushed super-stories into the darkness in 1986. Since then, his vast repertoire of books like V for Vendetta, From Hell, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, and more continue to showcase his stunning attention to detail and his mastery of a medium that he keeps pushing toward maturity.

10. If You Like to Be Scared

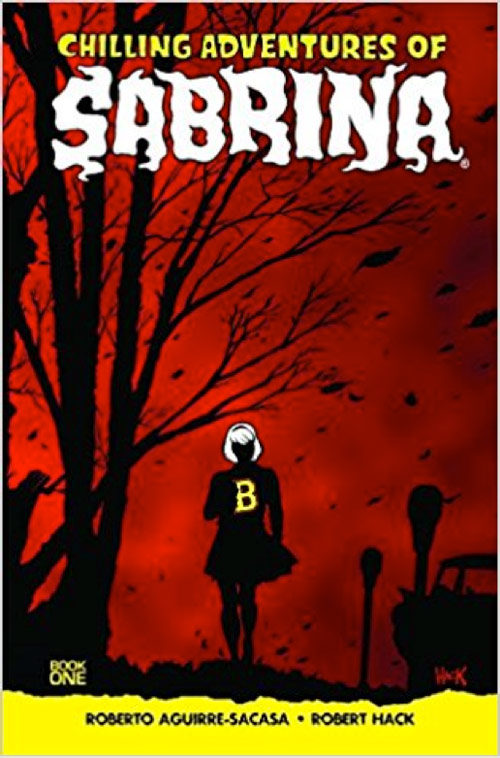

Well, you’re in luck. Horror abounds in comics. Easily the bestselling horror series of the last decade is The Walking Dead, basis for the TV show with a massive fanbase; if you follow Rick, Michonne, and Negan, it all started here. I also heartily endorse Uzumaki by Japanese horror manga legend Junji Ito; a masterwork of paranoia and Cronenbergian “body horror,” it’s an incredible unsettling read. And if you’re wondering why I haven’t mentioned Archie yet, that’s because I’ve been saving it. In the past few years, Archie Comics have totally reinvented themselves with a variety of series that take the characters into startling new directions. Two of the best are the horror titles Afterlife with Archie and Chilling Adventures of Sabrina, both written by Archie Comics Chief Creative Officer Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa (who also developed, executive produces, and writes for the Archie-derived TV series Riverdale).

Get out to your own local comic shop (or local library; graphic novel sections are huge there) and find what you like. And feel free to make your own recommendations in the comments below!

Funny Business: Why the Comedy Club Scene Is Booming

The comedy gods have not been kind to Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Nitwits, Funny Bone, Wacko’s — the city’s three top clubs — all shut down in the last year or so, the yuks yielding to economic reality. But a new venue, called Boss’, has leapt in to fill the void. It’s situated inside a chicken-and-pizza joint. Seriously.

That’s almost funny — possibly even to the itinerant comics who count on the country’s club circuit for their livelihoods. It’s a peculiar bunch, these touring stand-ups. If they’re good enough, every weekend they climb on stage to deliver a set of jokes to a crowd that’s alcohol-primed and rowdy. It can be brutal.

And yet, Sioux Falls’ issues notwithstanding, club comedy is in the midst of a boomlet in America. The streets are alive with the sound of guffaws.

It’s no shocker, then, that wannabe comics are abundant. Where once kids coming out of college aimed to be hedge-fund traders, some of today’s grads actually see comedy as a legit option. That’s a crack-up, eh?

“You can make an amazing living doing stand-up, but you have to love it,” I was told by Bruce Smith, who heads Los Angeles-based Omnipop Talent Group, which mainly represents comics. “It’s a high price you’re paying.” By which he means the constant travel and the crummy hotels in which club owners frequently house their performers. “There are a lot of indignities in comedy,” Smith told me.

Andy Kindler knows from indignities — oy! — but also the unparalleled high of being on a stage with nothing but a handheld mic. Kindler is one of the fortunate ones, a comic who’s worked pretty much nonstop since 1987. “Overall, it’s a way better scene now,” Kindler said from his home in L.A. just before flying off to another gig. For one, social media has allowed comics to nurture their audiences. What hasn’t changed: the fun of mingling in the green room. “Hanging out with all the other comics keeps me sane.”

Typical of an ascendant stand-up whom Kindler might encounter backstage is Erica Rhodes, who was a little-known actress before deciding, five years ago, to take a shot at stand-up. At first, she told me, she was doing “bringer shows,” where you literally bring your own audience. It was degrading. Sometimes she bombed. There was no money. Things looked grim.

But who’s laughing now? Audiences aplenty. Today, Rhodes is a frequent headliner. She’s performed in at least 20 U.S. cities. (Plus she’s scored small parts on a few top TV shows, such as Modern Family and Veep.) On first seeing her name illuminated atop a club marquee: “It was cool, but it had no huge effect on me.” What? Like many comics, Rhodes has a hard time acknowledging success. The veteran Andy Kindler, who’s worked clubs with Rhodes, observed, “It’s a tough biz, but Erica’s doing it the right way. She’s been very relaxed.”

Rhodes is pleased — well, as pleased as a comic can be — to have broken through, despite the fact that it demands more travel. “Every club is so different,” she said. “And comics are all weird. Female comics can be cold to each other. Local comics can be arrogant. They all have insecurities.” Rhodes herself has an ample amount of those, which she readily confesses in her largely autobiographical act.

Will today’s thriving club scene last? Possibly. According to a recent Wall Street Journal story, “as the world becomes a more unsettling place, the comedy club becomes a haven of sorts.” And thus a predictable punchline: In especially troubled times, we Americans will go looking for laughter. Even, it would seem, in a Sioux Falls pizza parlor.

In the last issue, Neuhaus wrote about tattoos.

This article is featured in the May/June 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

The Funny Papers

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, before I was old enough to get a work permit, I delivered newspapers in my suburban Philadelphia neighborhood. You might say it was my first job in publishing. At the time, Philadelphia was a three-paper town: There was the Inquirer, the Bulletin, and the tabloid Daily News. Where I lived, we also had a local paper, the Norristown Times-Herald.

First, I delivered the evening Bulletin (its slogan: “In Philadelphia, nearly everybody reads the Bulletin”) daily and Sundays. It was heavy with advertising, especially on a week leading up to a holiday, and I would pile the papers on a Radio Flyer wagon that I hauled up and down the streets like an undersized tugboat pulling a coal barge upriver. If the weather was especially rotten, my sainted mother would drive me around in the family station wagon. But I was usually on my own — come wind, rain, or snow. After two years humping the Bulletin, I jumped at the chance to deliver the much thinner Times-Herald. The route was smaller, there was no Sunday edition, and it actually paid better. I did that until I landed a job bagging groceries at a local supermarket.

Looking back, being a paperboy was a formative experience. I earned decent money for a 14-year-old; I learned how to sell subscriptions and keep payment records; I got to meet the neighbors (and their daughters). But above all, I got to see the funnies before anybody else. I would cut open the bundle, fish out a fresh copy, and settle back for some chuckles and thrills before heading out on my route.

It was then that I fell in love with comic strips in all their glorious variety — humor, adventure, romance, you name it. I had favorites — Peanuts, Prince Valiant, Pogo, The Phantom, Blondie, Li’l Abner — but I would also get caught up in the soap operas unspooling in the likes of Brenda Starr, Mary Worth, and Rex Morgan, M.D. Over the years, some old favorites faded away, as did the Philadelphia Bulletin, but inventive new strips like Doonesbury, Calvin and Hobbes, Bloom County, and Mutts arrived on the scene and took the comics in wonderful, sometimes challenging, directions.

Today, wherever I am, I still open the paper to the “funny pages” first thing to start my day with a smile. But I am in increasingly diminished company, as newspapers have consolidated or shut down across the country and readership has dropped dramatically. The numbers tell the tale: In 1960, there were 1,763 total daily newspapers (morning and evening) with a total circulation of 58,882,000; in 2014, there were 1,331 with a total circulation of 40,420,000. Meanwhile, average daily newspaper readers are now in their mid-50s and getting older. And reading the newspaper is not a habit with younger generations, who prefer to get their news online (ironically, often at newspaper websites) or via social media like Facebook or Twitter. Even some of my own contemporaries tell me that they don’t read the print newspaper. “Print, how quaint,” they sniff.

Despite such chattering, I believe we can say with assurance that print is definitely not dead and newspapers will endure, albeit as less of a fixture in daily life than in years past. But what do these demographic and digital changes bode for the comics, an indigenous American art form that has entertained hundreds of millions of readers — including me — since the turn of the 19th century?

I set out to ask some folks who would know.

If there’s such a thing as comics royalty, Brian Walker is it. His dad, Mort Walker, created Beetle Bailey in 1950 and is still penciling it at age 93. The perennially popular strip set in Camp Swampy and starring the goof-off private and his nemesis Sergeant Snorkel currently appears in 1,800 papers around the world. (Fact: Like many young artists in the late ’40s and early ’50s, Mort Walker contributed gag cartoons to The Saturday Evening Post before gaining fame with his comic strip. Beetle himself was named after Saturday Evening Post cartoon editor John Bailey.)

The younger Walker is also a historian, the author of The Comics: The Complete Collection (Abrams ComicArts), an indispensable and authoritative (and big!) survey of the strips and artists who have delighted readers from the 1890s to the 21st century, from The Yellow Kid and Little Nemo in Slumberland to Zits and Pearls Before Swine.

—UClick’s John Glynn

In The Comics, he makes a compelling case for the comics as a singular art form, writing, “Cultural elitists relegate comics to the status of ‘low art.’ Cartoon art should not be judged by the same criteria as fine art. Comics are a unique visual and narrative art form, and both elements should be considered when evaluating the work of an individual cartoonist. Comic creations are also the products of the culture within which they are produced. All these factors must be taken into account when developing an appreciation for cartoon art.”

Finally, he’s a cartoonist in his own right, collaborating since the early ’80s with his brother, Greg Walker, and other artists on Hi and Lois, which was created by Mort Walker and the late Dik Browne (Hägar the Horrible) in 1954 and appears in 1,000 papers today. (Fun fact: Hi and Lois Flagston are Beetle Bailey’s sister and brother-in-law.)

So, you take him seriously when he says, “I wouldn’t recommend newspaper cartooning to an aspiring artist — it’s not a growth industry.”

Indeed, with circulation declining and more and more readers getting their news online, print newspapers nationwide have been allotting less space to the funnies. That and canceling strips that don’t score well in reader polls. In a few instances, even the venerable Beetle Bailey has been dropped as struggling newspapers fold or cut costs by eliminating older, more established (and more expensive) strips. Meanwhile, Walker explains, the major syndicates that distribute comic strips are paying “next to no money” to new artists. “They’re practically giving away new strips,” he says.

At the same time, syndicates like Universal Uclick and King Features are putting their comics online for the enjoyment of the millions of fans who don’t read print newspapers or can’t get their favorite strips in their local paper. “The internet changed the game,” Walker says. “The syndicates were rather slow to jump on the web, thinking their newspaper clients would be upset. They’ve since gotten savvier about expanding their presence in social media with sites like GoComics.com and ComicsKingdom.com, blogs, and Facebook.”

Asked to put on his historian’s hat and name a Golden Age of comics, Walker points to the ’30s and an “explosion of creativity” that brought about such classics as Flash Gordon, Dick Tracy, Prince Valiant, Popeye, Blondie, and Li’l Abner. The decade is also memorable, he says, for the rise of the adventure strip with its long-running story lines and danger-defying heroes (e.g., Terry and the Pirates and Mandrake the Magician) that delivered thrills by the panel-full over the years.

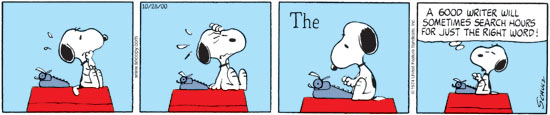

Walker then fast-forwards five decades to the emergence of the baby-boomer artists of the ’70s and ’80s who ushered in a “renaissance” of comics art. “The new generation was inspired by Charles Schulz’s multidimensional characters,” he says. Although children, Charlie Brown, Lucy, Linus, and the rest of the Peanuts crew grappled with such adult, existential issues as loneliness, disappointment, failure, and loss. With the massive success of Peanuts, Schulz established that a cartoonist could examine the darker aspects of everyday life and still provoke a smile. For the Me-Generation cartoonists, this was a clarion call: What better life to examine than your own? And the time was right for a new approach. “Tastes had changed,” explains Walker. “Readers wanted to see themselves and their experiences in the strips. In the classic era, the artist was in the shadows, behind the scenes; the boomer artists were more autobiographical. When you read strips like Doonesbury, Cathy, Dilbert, and For Better or Worse, you were getting a glimpse into the lives of the artists.”

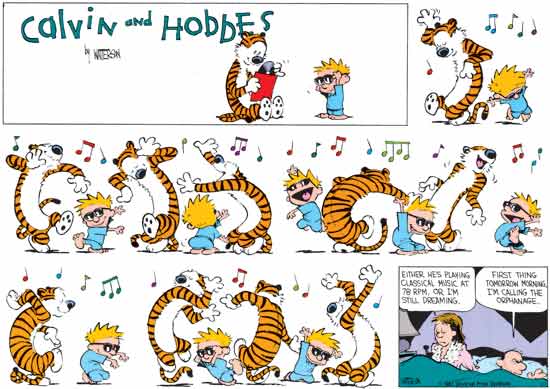

The new comics cadre also catered to the irreverent, anti-authoritarian spirit of the times with unconventional, envelope-pushing strips like the (sadly) short-lived The Far Side, Bloom County, and Calvin and Hobbes, this last chronicling the adventures of a wildly imaginative 6-year-old boy and his stuffed toy tiger. “If pressed to name the best comic strip of all times,” Walker says, “I’d have to say Calvin and Hobbes. It works on so many levels.” Indeed, aside from Peanuts, no modern strip has had such an influence and won such acclaim.

Hi and Lois, on the other hand, has been a quiet success for 62 years, as the immutable Flagstons navigate life in suburbia together. With its gentle life lessons and G-rated humor, Hi and Lois offers a sweet counterpoint to the snark and surreal antics of newer strips. “They’re a functional family in a dysfunctional world,” Walker says. “I get nice letters from mothers.”

In the Flagstons’ world, things change over time without really being that noticeable (with the exception of Chip aging into a teenager). “We now have computers, cellphones, flat-screen TVs, and things like that,” Walker explains, “but that’s just the background.”

The one thing sure to never change is the bond between the family members, which can be difficult to capture in a couple of panels. “It’s challenging to show love in a strip,” says Walker, who credits The Family Circus creator and friend Bil Keane with being an inspiration. “He gave me the courage to do things that are sweet and loving.”

But while the Flagston world may change incrementally, Hi and Lois itself has embraced the digital age. There is a Hi and Lois website (HiandLois.com), which attracts thousands of visitors a week with new strips, a weekly blog by Walker, and access to an archive of decades of vintage strips. And these days, the classics must maintain a presence on social media: both Hi and Lois and Beetle Bailey have Facebook pages boasting more than 2,500 likes each.

In another telling sign of the times, Walker’s own comics-reading habits have changed. “I buy the Sunday paper,” he reports, “but for daily comics, I go online to the syndicate sites where I can keep up on strips that never run in my local paper.”

© Bill Watterson, reprinted by permission of Universal UClick, All rights reserved

Asked about the condition of the newspaper comic strip today, King Features Syndicate Editor Brendan Burford paraphrases Mark Twain’s famous line: The report of its death was greatly exaggerated.

Yes, he acknowledges, print has been in decline, but “there’s no reason to think because there’s a contraction in newspapers that people are going to stop reading and enjoying comics. Overall, our business has been stable.”

Launched in 1915 by legendary publisher William Randolph Hearst, King Features is the second-largest comics syndicate after Universal Uclick. It currently syndicates 62 comic strips to newspapers worldwide and maintains an extensive archive of vintage strips on its website, ComicsKingdom.com. The King Features roster runs the funnies gamut: from boomer faves Mutts and Baby Blues to such old-school stalwarts as Mary Worth and Mark Trail — along with some of the biggest titles in the business. “The number of comic strips we license to more than a thousand clients — strips like Dennis the Menace, Hägar the Horrible, Family Circus, Beetle Bailey — is remarkable,” Burford says. “That’s rare air.”

Still, growth is hard to come by, especially in newspapers, where King Features is competing for space with other syndicates. “Our newspaper clients want something fresh,” says Burford, who has seen tastes change in his 15 years at the syndicate. Adventure comics are on the wane, as readers get their escapist satisfaction in comic books, television, and movies. “People now want to see themselves and their friends,” he says, echoing Brian Walker. “They want a reminder that life has levity.” To prove the point, he cites the enormous popularity of Zits, which features the foibles and fantasies of teenager Jeremy Duncan — and the reactions of his often perplexed parents. “It’s a reflection of today’s family.”

To find that “something fresh” for his clients, Burford sifts through “thousands of submissions” from would-be syndicated cartoonists every year. Sadly, of those few that show promise, he says, “I can only run with one or two” in today’s tight market — which can be frustrating for a syndicator. “I wish we could represent all the talent we like.”

As for the 62 active strips it does represent, King Features has assembled the whole batch, along with a library of vintage comics, on the web at ComicsKingdom.com. For fans of the funnies, this is liberating stuff. No longer get Crankshaft or Judge Parker in your local paper? You can catch up with them online. Or browse past installments of classics like Krazy Kat, The Katzenjammer Kids, and Popeye. Even better, you can subscribe to the site and have your favorite strips emailed to you daily.

Over at rival syndicate Universal Uclick, President and Editorial Director John Glynn remembers being told in 2000 that there “wouldn’t be newspapers by 2010.” Nearly seven years past that deadline, the largest independent syndicate in the world represents more than 80 active comic strips in approximately 2,000 papers worldwide, including such legendary strips as Garfield, Doonesbury, Peanuts, and Dilbert — all of which appear in thousands of newspapers around the world — plus offbeat hits like Pearls Before Swine, Foxtrot, and Get Fuzzy. “Newspapers will be here, one way or another,” says Glynn, “and it wouldn’t be a newspaper without comics.”

Universal Uclick also runs a website, GoComics.com, where funnies fans can browse day-of-publication installments of Universal Uclick’s active strips, plus an archive of such classics as Peanuts, For Better or For Worse, Dick Tracy, and Alley Oop. One of the beauties of the web, he says, is “there is no limitation to the real estate.” Which makes it possible for them to distribute some 400 strips digitally. (In a bit of irony, they syndicate comics to newspaper sites looking to improve on their limited print offerings. “They can carry as many as 40 to 60 strips online with us,” Glynn says.)

In Glynn’s view of the future, “newspapers will hang on” while the funnies will continue to find new markets. “We’ll deliver comics to wherever people are reading them,” he says, “be it newspapers, desktops, tablets, or smartphones. I’m a big believer in the medium,” Glynn says, “I think of them as ‘snackables’ that brighten the day.”

Glynn might have had Pickles in mind. The award-winning, G-rated, gag-a-day strip that celebrated its 25th anniversary in 2015 is a welcome tonic in trying times. A former graphic designer turned cartoonist, Pickles creator Brian Crane takes a sweetly wry look at the lives of 70-something retirees Earl and Opal Pickles and their family and pets. Married 50 years, Earl and Opal have learned to (sometimes grudgingly) accept each other’s quirks as they grow old together, while imparting their accumulated wisdom and humor to the younger generations.

Looking back, Crane considers himself lucky to be where he is today. “I was a long shot to get syndicated,” he says. “You’d get better odds at a racetrack.” Nevertheless, the 40-year-old novice had encouragement on the homefront — “my wife kept pushing me to submit my work” — and after only three rejections, he was a syndicated cartoonist, right in the midst of what was allegedly an imploding market for newspaper comics. “That’s what they told me in 1990, and papers have gone out of business on me,” he says. “But I’ve weathered the storm pretty well. I’m almost always on top of reader polls, and I’m closing in on 1,000 papers.”

Not surprisingly, the Pickles readership skews older — but not exclusively. “When I speak at events,” Crane says, “there’s a lot of gray hair in the audience, but I do well with younger folks in reader polls.” How to account for the strip’s multigenerational appeal? “I’ve heard it from folks a thousand times,” says Crane. “They tell me, ‘You must have a microphone hidden in our home!’” It doesn’t hurt that Crane maintains a strong digital presence. Pickles is carried online by GoComics.com/Pickles and ArcaMax.com, where it is enjoyed by tens of thousands of fans. And the Official Pickles Comic Page on Facebook — which posts the daily strip, past favorites, videos, reader comments, and personal shares — had amassed more than 34,000 likes at last count.

Crane’s hero is Charles Schulz, whose approach to Peanuts and life Crane admires. “He was humble and kind,” he says. “He never went the easy route, never coasted.”

It’s an ideal that Crane tries to follow in a hyper-competitive business. “I can’t rest on my laurels,” he says. “My daily challenge is to be funny today. I keep trying to surprise myself, looking to find things in my own life that spark ideas.” He doesn’t have to look all that far: With seven children and 11 grandchildren of his own, Crane literally inhabits the world of doting — and occasionally dotty — grandparents Earl and Opal Pickles.

There has always been an underlying purpose to Pickles, Crane says, which is “to point out that being older is a good time to be alive; to laugh at the foibles of growing old.” And, today, 26 years after breaking into the comics business, he wouldn’t change a thing about his own life: “From my myopic point of view, it’s a nice situation for me. I write something that makes me happy.”

Like Brian Crane, Pearls Before Swine creator Stephan Pastis ditched a paying career to follow his dream. Unhappy with practicing law in the San Francisco Bay area in the mid-’90s, he decided “I have to do something else” and began cartooning. Pastis studied Dilbert to learn how to write a three-panel strip. In a bold step, he approached Charles Schulz himself at a Northern California skating rink coffee shop and asked for advice. (Schulz was gracious and helpful.) He also recruited Darby Conley of Get Fuzzy fame for input on coloring the artwork. After submitting various strips “five or six times” to syndicates, he clicked with Pearls Before Swine, which debuted online in 2000 in a test by United Features Syndicate, and then in newspapers on December 31, 2001. In 2002, he quit his day job and became a full-time cartoonist.

Today, Pearls Before Swine is carried by 750 papers worldwide and growing. The strip (gocomics.com/pearlsbeforeswine) chronicles the exploits of Rat, Pig, Goat, Zebra, and a crew of delightfully dimwitted Crocs who speak with a mysterious, unidentifiable accent. Regular targets of his snarky humor include vegans, bikers, other strips (e.g., Cathy, The Family Circus), and sometimes even Pastis himself. Often controversial for its adult humor and eagerness to test the boundaries of propriety (is that a swear word I see?), Pearls Before Swine has nevertheless won the National Cartoonists Society’s Best Newspaper Comic Strip award three times and been nominated eight times for the Reuben Award, the society’s highest honor. “You’re not artistic or creative if you’re not pushing the boundaries,” he says.

Part of the secret is being true to himself. “If you write honestly, your body of work reveals who you are,” he says. “If you’ve read the strip faithfully for 15 years, you know me as well as my relatives.”

It’s a successful approach that no longer relies on newspapers alone. Cartoonists today need to diversify and self-promote relentlessly. “To be famous these days, you have to be famous in a number of piles — newspapers, books, music, cable, social media,” Pastis says. “Everybody is hustling harder, even a superstar like Bruce Springsteen has to do a lot more promotion than he did in the ’70s.” There are 18 Pearls Before Swine collections and eight treasuries, plus merchandise (T-shirts, mugs, plush animals, etc.), and Timmy Failure, a best-selling series of chapter books aimed at middle schoolers. The Stephan Pastis Facebook page has upwards of 154,000 likes as this article goes to press. “It’s a revolution,” he declares. “The winners will adapt. With the internet, you now have the ability to address people directly and react to events quicker. I have more fans in Mumbai than in any other city in the world.”

Of course, all the marketing and promotion in the world won’t sell your work if it doesn’t strike a nerve. A sociologist might say the secret to the success of Pearls Before Swine lies in Pastis’ ability to tap into the current snarky zeitgeist using angry Rat, naive Pig, bookish Goat, even the inarticulate Crocs, as his stand-ins. The artist himself makes no such claim, suggesting instead, “It’s sheer, dumb luck it worked.”

I’m sure Rat would disagree.

As a lifetime fan of the funny pages, I’m gratified that many of the great ones continue to thrive. As Brian Walker writes in The Comics, this particular art form has endured because the funnies have timeless appeal. “Their daily appearances make them familiar to millions. Their triumphs make them heroic. Their struggles make them seem human. Cartoonists create friends for readers. Pogo, Peanuts, Calvin and Hobbes, and Dilbert are part of a great cultural legacy that is being further enriched every day. The final panel has yet to be drawn.”