North Country Girl: Chapter 5 — Congdon Elementary

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

Congdon was a big red brick pile built in 1929 and unchanged since. My second grade class still had wooden desks with ornate cast iron sides, holes in the upper right hand corner for inkwells, and decades of names scratched into the surface, even though making yet another mark on your desk was a major sin, practiced exclusively by boys. Heating vents honey-combed the building, just big enough for a child to crawl through. Everyone knew of a former student who had traveled the vents from the basement to the second floor. As the smallest kid in my class, I was egged on by my peers to repeat this journey; I bravely crept in about three feet before scurrying back out to the light.

The school had a huge gym, which was transformed into a performance space for Congdon’s annual Christmas Concert, where students sang “Silent Night” and “Up on the Rooftop” and a hundred other carols while standing around a twenty-foot Christmas tree, surrounded by concentric circles of parents perched on ancient and shaky folding chairs. We practiced for weeks for this concert. The handful of Jewish kids were left on their own for hours on end in their classrooms, to read or draw or twiddle their thumbs.

One side of the gym was a high, deep stage; it was expressly forbidden to jump on the stage and hide behind the red velvet curtains. I only saw the stage used once, when we were trotted down to the gym for a slide show of some woman’s trip to Korea, Thailand, and Cambodia. What a wonder! Someone from Duluth had actually gone to Asia! (A few years later, my paternal grandparents went to Hong Kong; my grandmother smuggled back an entire custom-made wardrobe by wearing all her new suits and dresses and coats on top of each other.)

The gym was a place of dread for me. I hated every gym class, including square dancing (which seems to have been a mandatory part of PE at all elementary schools in the country then), but apparatus day set me quaking in fear. When not in use, the “apparatus” was hung about the walls of the gym like instruments of torture. The rings weren’t so bad, I could hang by my knees forever, enjoying the rush of blood to my head, until I was kicked off by the next kid in line. But there were also climbing bars, which required chin-ups at the top, the ropes (how could it have been thought okay to send kids ten feet up in the air clinging to a rope so splintery it would have been rejected by the most horny-handed sailor, below only a mouldering two-inch-thick gym mat held together with duct tape to soften the fall?), and worst of all, the horse. My version of a vault was to run up to the horse, come to a dead stop, then heave myself over, struggling to land on my feet instead of my head.

All of our gym activities were overseen by our classroom teachers, who were uniformly unmarried, over fifty, and in varying degrees of unfitness, the worst being Miss Johnson, my fifth grade teacher, who was Mrs. Sprat fat. Our principal, Miss Brown, was of the same graying spinster ilk. The only masculine figure at Congdon was Mr. Swan, the janitor, who took the gym apparatus up and down, flooded and swept the Congdon ice rink in winter, and who could usually be found smoking a vile cigar down in the boiler room, poking at the roaring coal-burning furnace. Any classroom accident or breakage required someone to go down to that dungeon and bring back Mr. Swan with his mop and bucket. I always tried to hide beneath my raised desktop rather than have to face that scary man in his den. For any other errand, when a teacher asked for a volunteer, my hand shot up first.

A school telephone system had once been in place, as there were rudimentary black Bakelite and brass phones on the classroom wall, but they had long ceased to function, so students were sent as messengers back and forth, a wonderful chance to dawdle in the deserted halls, take a long gulp of cold water from the fountain, and hang around the principal’s office in hopes of seeing some bad boy brought in by the scruff of his neck to face Miss Brown.

Supply Monitor was the most prestigious and sought-after job, responsible for fetching chalk or construction paper each morning from the school’s supply room. I was often awarded this plum position; I was well-behaved, quiet, and a model student, which did not win me any friends.

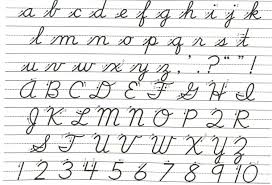

I sailed through second grade, except for two subjects. We were now expected to stop printing in pencil and learn cursive writing, including the weird capitals S, Q, and G that bore no resemblance to their print counterparts. All of the letters in a word were supposed to flow from the pen, all connected smoothly at the bottom, with the top of lower-case letters exactly touching the dotted line bisecting each row. Not only did this require a level of manual dexterity I would never have, we also had to write with a fountain pen. Each student was given a brightly colored plastic pen, perfect to chew on, and a small supply of cylindrical ink cartridges. I was unable to insert the cartridge in the pen without exploding blue ink everywhere. My mother would shake her head at my stained dresses and my unvarying “C” in penmanship, which would probably have been a D if I didn’t get A’s in everything else.

I also could not learn to tell time. Periodically during the school day we were required to look at the wall clock and write down the time. After weeks of failing to identify 10:30 or 1:45, it was discovered that I couldn’t see the hands of the clock. I was now the youngest, smallest, and only second grader with glasses. From the meager selection of children’s glasses at the eye doctor, I had picked out pale blue cat’s eyes, with silver sparkles at the corners to make a bad situation even worse.

I also could not learn to tell time. Periodically during the school day we were required to look at the wall clock and write down the time. After weeks of failing to identify 10:30 or 1:45, it was discovered that I couldn’t see the hands of the clock. I was now the youngest, smallest, and only second grader with glasses. From the meager selection of children’s glasses at the eye doctor, I had picked out pale blue cat’s eyes, with silver sparkles at the corners to make a bad situation even worse.

A few Congdon kids went home for lunch, most of us ate in the cafeteria at long wooden tables. Four days a week I got the “hot lunch,” which I retrieved on a tray from a small opening in the front of the cafeteria that gave way into a dimly lit kitchen ruled by mysterious lunch ladies. There was “lunch money” and “milk money,” which we had to remember to bring to school every Monday. Milk money went to buy waxy containers of milk to drink if you brought your soup and sandwich in a tin lunchbox that proclaimed your favorite TV show. This milk always tasted funny compared to our milk at home, which was delivered in glass bottles topped with paper discs labeled Springhill Dairies. Two or three times a year, there would be the miraculous appearance of cartons of chocolate milk, which we fell upon like wolves. On Fridays, to accommodate the few Catholic students who could not eat meat, lunch was always tuna noodle casserole, the noxious smell of which made me so nauseated I could barely eat my sandwich of red jelly on white bread.

Featured image: Shutterstock