America’s (Not Quite) First Bank Robbery

This piece was originally published as “America’s First Bank Robbery,” but a recent note (March, 2015) from Adam Berlinger brought to our attention an earlier bank robbery than the one described here. Berlinger sent us a link to an article entitled “America’s First Bank Robbery” (a very fine title) written by Ron Avery, which describes the removal of $162,821 from the Bank of Pennsylvania at Carpenters’ Hall in 1798.

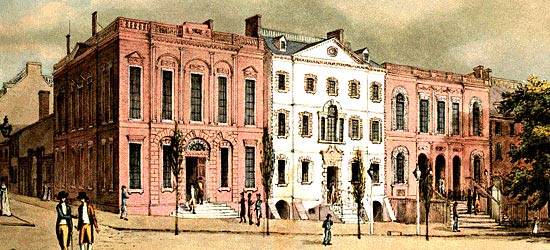

Late on the night of March 20, 1831, two men with a set of homemade keys approached the City Bank of New York. The keys, which had been made from wax impressions of the door locks, enabled the men to let themselves into the bank and lock the doors behind themselves.

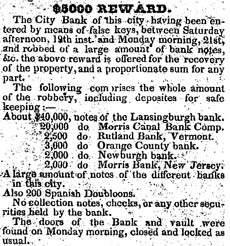

What happened that night is generally considered to be the first bank robbery in the U.S. The two men—James Honeyman and William J. Murray—emptied the vault and several safe deposit boxes. By the morning, they had filled several bags with $245,000 in bank notes and coins. It was an incredibly large sum for a robbery, roughly equivalent to $52 million today. The robbery was sensational enough to be rushed into print in the next edition of the Post, under a bold headline offering “$5,000 Reward.”

Honeyman and Murray got away the next morning as the sun rose and the city’s night watchmen went off duty. Carrying the loot under the large capes they were wearing, they hurried to Murray’s house where they divided the money.

Honeyman put his share of the loot into three trunks, then drove to a boarding house, where he rented a private room under the name of Jones.

Less than a month later, the Post was able to report that “something peculiar in his conduct, particularly regarding the trunks, seems to have excited the suspicions of his landlord.”

Once in the rooms, Honeyman divided the stolen money again, taking $37,000 to the house of a Mr. Parkinson, his brother-in-law.

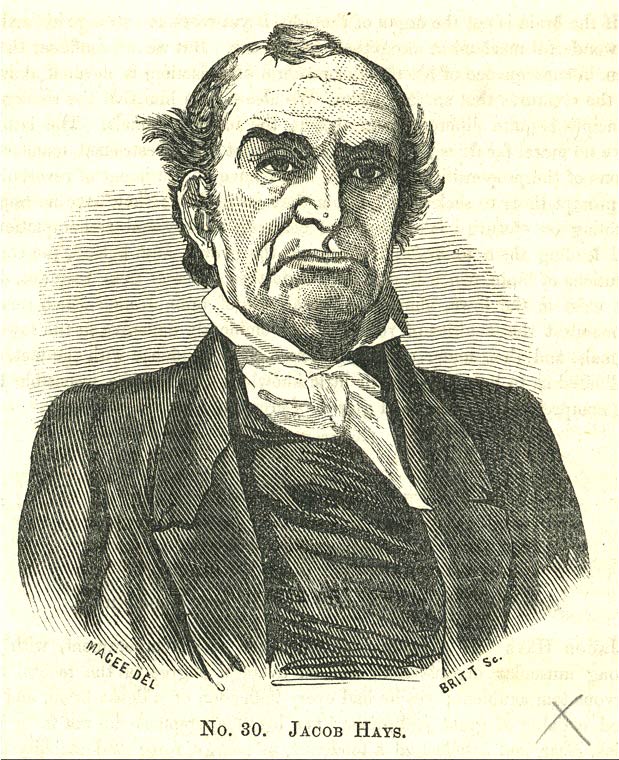

Meanwhile, news of the bank robbery had sped across town and reached the ears of New York’s Chief Constable Jacob Hays. He immediately knew whom to suspect. Honeyman had recently been charged with robbing a store in Brooklyn, but had escaped conviction due to lack of evidence. He had also been caught trying to steal money from a steamboat. And there were rumors that he was still the chief suspect in an English mail-coach robbery. Hays immediately went to Honeyman’s home, but found neither his suspect nor any money.

The following Saturday night, March 24, Honeyman left the boarding house with one of the trunks and told the landlord he would soon return for the others. The landlord, now convinced the trunks contained the stolen bank money, summoned Hays. Together, they opened the remaining trunks where they found $185,758.

The men seated themselves and waited. Three hours later, when Honeyman walked into the room, Hays seized him, put him in handcuffs, and took him before a judge.

The landlord also told Hays that another man had often visited Honeyman. From the description, Hays recognized the man as Murray. The two men were frequently seen together. In fact, they had been close friends ever since meeting in the penal colony at Botany Bay. Both men had beat long odds and escaped Australia to return to England, commit a few more robberies, then flee to the states.

After depositing Honeyman in jail, Hays went to Murray’s house but found the man had fled to Philadelphia. Hays followed after, apprehending Murray and bringing him back to New York for trial.

Both Honeyman and Murray were convicted and sentenced to five years at New York’s Sing Sing prison.

Hays recovered about $176,000 of the stolen money, but had no idea where to find the remaining $69,000. Months passed by, and his searches turned up nothing. City officials accused Hays and one of his associates of keeping the money to themselves.

Then, on September 20, Parkinson entered a bank to exchange some of the bank notes Honeyman had left with him. The bank clerk thought the notes resembled those he had deposited at the City Bank before it was robbed. He notified Hays, who quickly arrested Parkinson. He told the police all he knew and, in exchange for immunity, returned $37,000.

This still left $42,000 unaccounted for, but Hays was exonerated in public opinion. The Post’s editors felt that now, even the most skeptic would see “Mr. Hays is worthy of the important situation which he has so long filled.”

Hays even had the support of the men he’d put behind bars, the Post reported. “While Smith [one of Honeyman’s aliases] and Murray were in prison, awaiting their trial, they were informed that Mr. Hays was openly charged with abstracting that part of the money which was missing. They expressed great indignation at so malignant an accusation and stated that the amount not found had been placed beyond the reach of Hays before Murray was arrested. It can hardly be supposed that any unworthy suspicions can now be attached to this meritorious public servant, who had passed the prime of his years in the discharge of an arduous and unpleasant duty.”