What to Do in Your Kitchen All Day: Beans, Baking, and Braising

Millions of us have taken to our homes during this unprecedented global pandemic. Social distancing is tough, but we all have to do our part in slowing the spread of the virus. If you’ve considered yourself a neophyte in the kitchen, this could be your chance to bone up on baking and slow cooking. Since you’re going to be home for days at a time — and you’re likely cooking anyway — you may as well get some gourmet food out of it. When life hands you isolation, make bread.

Sourdough Starter

Drop everything and mix up a sourdough starter, or levain, right now. In less than a week, you’ll have all you need to bake a wonderfully chewy, crusty loaf of bread.

Sourdough starter is a gooey paste that captures and activates wild yeast to be used for baking. It’s so easy to start, and once you have it you can keep feeding it indefinitely or gift some to friends.

Ingredients

- 1 scant cup flour (x5)

- ½ cup warm water (x5)

Directions

- Mix up the flour and water in medium-to-large glass bowl. Make sure it is mixed thoroughly. Cover the bowl with a towel or plastic wrap and set somewhere warm (around 70-75 degrees).

- Every 24 hours, “feed” the starter with one scant cup of flour and ½ cup warm water and mix it in thoroughly. By the third or fourth day, your starter should be bubbling and smell sour. After the fifth day, discard half the starter (or use it) before feeding. To keep it longer, keep it in the refrigerator, feeding it weekly, or dry it out by smearing it on a cutting board and keeping the flakes in an airtight container.

Walnut Cranberry Loaf

Now that you have your sourdough starter, you can put it to use baking some tasty loaves. Since you won’t be using active dry yeast in this bread, giving it the proper time to rise is crucial. Once you’ve made your first loaf of bread, you can dive into the intricacies of breadmaking. This one is perfect for morning toast or a heavenly turkey sandwich. You’ll be the envy of everyone on your video conference call.

Ingredients

- 1 ½ cups sourdough starter

- 3 cups all-purpose flour

- 1 cup water

- 1 ½ tsp salt

- ¾ cup dried cranberries

- ¾ cup shelled walnuts

Directions

- In your mixer (or with a wooden spoon), combine the starter, flour, water, and salt. Cover and let it sit for an hour.

- Knead the dough using your mixer (or your hands) for five to ten minutes. Add the cranberries and walnuts and lightly fold them into the dough. Let it rest another hour.

- Form the dough into a ball and place it on an oiled pan or cooking stone (the one you will use to bake it). If your kitchen is hot, cover the dough and place the pan in the refrigerator to rise overnight. Otherwise, it can sit covered overnight on the counter.

- Preheat the oven to 450 degrees F and place a pan on the bottom rack. Pour two cups of water into the pan once the oven is hot. When the water starts boiling, put the dough in the center rack. Bake for 30-40 minutes, watching closely for a golden-brown crust. Let the bread cool on a cooling rack.

Baked Black-Eyed Peas

These beans are so versatile you’ll never run out of uses for the leftovers. Make them spicy or tangy and sweet. Substitute any medium-sized bean like adzukis or white beans. Put them on toast with a fried egg and chopped scallions, or serve them on a bed of coconut rice with a cut of pork.

Ingredients

- 3 cups dried black-eyed peas

- 1 tbs extra-virgin olive oil

- 2 onions, sliced

- 2 carrots, chopped

- 1 stalk celery, chopped

- ½ head cabbage, chopped

- 4-6 garlic cloves

- 3 bay leaves

- 5 sprigs fresh thyme

- 2 tsp chili powder

- ½ cup dry white wine

- 1 tsp chicken bouillon (or vegetable bouillon)

- ½ cup fresh grated parmesan or romano cheese

- Salt and pepper

Directions

- Soak the beans overnight in a large mixing bowl with two extra inches of water. Drain and rinse them when you’re ready to cook.

- Preheat oven to 300 degrees F.

- In a large dutch oven, heat the olive oil on medium heat and add onions. Caramelize the onions (you have time, right?) by cooking them until they are a deep tan color (about 45 minutes).

- Add the carrots, celery, and cabbage and continue cooking for about 5 minutes. Add garlic and cook for another 5 minutes.

- Deglaze the pot with the white wine. Cook for about a minute, then add the chicken bouillon, beans, thyme, bay leaves, chili powder, and enough water to cover it all. Bring the pot to boil, then cover and put into the oven. (You can instead transfer the contents to a slow cooker at this point if you’d prefer.)

- Cook for four to six hours, covered. Uncover, stir in cheese, salt, and pepper, and bake, uncovered for another half-hour to an hour.

Khara Masala Braised Leg of Lamb

This recipe was adapted from an old Indian cookbook I found in a used bookstore years ago. If you’re reticent to cook lamb, this will make a believer out of you. I serve it with curried cauliflower and super spicy cabbage.

Ingredients

- 1 6-8-pound leg of lamb, bone in

- 2 tbs extra-virgin olive oil

- 2 medium onions, chopped

- 1 tbsp grated ginger

- 4 garlic cloves, sliced

- 6 whole dried red chiles

- 3 cardamom pods

- 2 cinnamon sticks

- 3 cloves

- Fresh cilantro

- 3 cups chicken stock

- Salt and pepper

Directions

- Turn on oven broiler. Salt and pepper the leg of lamb and place it on a pan on a rack in the center of the oven. Brown each side, about 20-25 minutes total.

- Preheat oven to 300 degrees F. In a dutch oven, heat oil on medium and add onions. Cook for five minutes, until translucent. Add ginger, garlic, and chiles, cooking for another five minutes.

- Remove from heat and add cardamom, cinnamon, cloves, cilantro, leg of lamb, and chicken stock. Cover and place in center rack of oven.

- Cook for around five hours, or until fork tender, occasionally spooning the stock over the leg of lamb. Serve with fresh cilantro. Strain the stock from the dutch oven to make gravy or refrigerate for later.

Featured image: Shutterstock

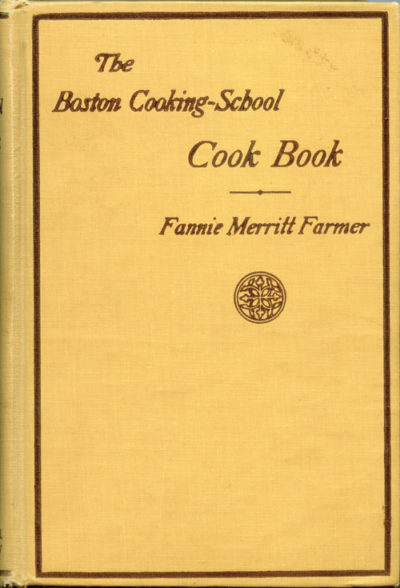

The Rise of Cookbooks in America

The first edition of The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book — now known as The Fannie Farmer Cookbook — reads like a road map for 20th-century American cuisine. Published in 1896, it was filled with recipes for such familiar 19th-century dishes as potted pigeons, creamed vegetables, and mock turtle soup. But it added a forward-looking bent to older kitchen wisdom, casting ingredients such as cheese, chocolate, and ground beef — all bit players in 19th-century U.S. kitchens — in starring roles. It introduced cooks to recipes like hamburg steaks and French fried potatoes, early prototypes of hamburgers and fries, and fruit sandwiches, peanuts sprinkled on fig paste that were a clear precursor to peanut butter and jelly.

Americans went nuts for the 567-page volume, buying The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book in numbers the publishing industry had never seen.

Americans went nuts for the 567-page volume, buying The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book in numbers the publishing industry had never seen — around 360,000 copies by the time author Fannie Farmer died in 1915. Home cooks in the United States loved the tastiness and inventiveness of Farmer’s recipes. They also appreciated her methodical approach to cooking, which spoke to the unique conditions they faced. Farmer’s recipes were gratifyingly precise, and unprecedentedly replicable, perfect for Americans with newfangled gadgets like standardized cup and spoon measures, who worked in relative isolation from the friends and family who had passed along cooking knowledge in generations past. Farmer’s book popularized the modern recipe format, and it was a fitting guide to food and home life in a modernizing country.

Recipes today serve many purposes, from documenting cooking techniques to showing off a creator’s skills to serving up leisure reading for the food-obsessed. But their most important goal is replicability. A good recipe imparts enough information to let a cook reproduce a dish, in more or less the same form, in the future.

The earliest surviving recipes, which give instructions for a series of meaty stews, are inscribed on cuneiform tablets from ancient Mesopotamia. Recipes also survive from ancient Egypt, Greece, China, and Persia. For millennia, however, most people weren’t literate and never wrote down cooking instructions. New cooks picked up knowledge by watching more experienced friends and family at work, in the kitchen or around the fire, through looking, listening, and tasting.

Recipes, as a format and genre, only really began coming of age in the 18th century, as widespread literacy emerged. This was around the same time, of course, that the United States came into its own as a country. The first American cookbook, American Cookery, was published in 1796. Author Amelia Simmons copied some of her text from an English cookbook but also wrote sections that were wholly new, using native North American ingredients like “pompkins,” “cramberries,” and “Indian corn.” Simmons’ audience was mainly middle class and elite women, who were more likely to be able to read and who could afford luxuries like a printed book in the first place.

The reach of both handwritten recipes and cookbooks would expand steadily in the coming decades, and rising literacy was only one reason. Nineteenth-century Americans were prodigiously mobile. Some had emigrated from other countries, some relocated from farms to cities, and others moved from settled urban areas to the Western frontier. Young Americans regularly found themselves living far from friends and relatives who otherwise might have offered help with cooking questions. In response, mid-19th-century cookbooks attempted to offer comprehensive household advice, giving instructions not just on cooking but on everything from patching old clothes to caring for the sick to disciplining children. American authors routinely styled their cookbooks as “friends” or “teachers” — that is, as companions that could provide advice and instruction to struggling cooks in the most isolated of spots.

Americans’ mobility also demonstrated how easily a dish — or even a cuisine — could be lost if recipes weren’t written down. The upheaval wrought by the Civil War singlehandedly tore a hole in one of the most important bodies of unwritten American culinary knowledge: prewar plantation cookery. After the war, millions of formerly enslaved people fled the households where they had been compelled to live, taking their expertise with them. Upper-class Southern whites often had no idea how to light a stove, much less how to produce the dozens of complicated dishes they had enjoyed eating, and the same people who had worked to keep enslaved people illiterate now rued the dearth of written recipes. For decades after the war, there was a boom in cookbooks, often written by white women, attempting to approximate antebellum recipes.

Standardization of weights and measures, driven by industrial innovation, also fueled the rise of the modern American recipe. For most of the 19th century, recipes usually consisted of only a few sentences giving approximate ingredients and explaining basic procedure, with little in the way of an ingredient list and with nothing resembling precise guidance on quantities, heat, or timing. The reason for such imprecision was simple: There were no thermometers on ovens, few timepieces in American homes, and scant tools available to ordinary people to tell exactly how much of an ingredient they were adding.

Recipe writers in the mid-19th century struggled to express ingredient quantity, pointing to familiar objects to estimate how much of a certain item a dish needed. One common approximation, for instance, was “the weight of six eggs in sugar.” They also struggled to give instructions on temperature, sometimes advising readers to gauge an oven’s heat by putting a hand inside and counting the seconds they could stand to hold it there. Sometimes they hardly gave instructions at all. A typically vague recipe from 1864 for “rusks,” a dried bread, read in its entirety: “One pound of flour, small piece of butter big as an egg, one egg, quarter pound white sugar, gill of milk, two great spoonfuls of yeast.”

By the very end of the 19th century, American home economics reformers, inspired by figures like Catharine Beecher, had begun arguing that housekeeping in general, and cooking in particular, should be more methodical and scientific, and they embraced motion studies and standardization measures that were redefining industrial production in this era. And that was where Fannie Merritt Farmer, who started working on The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book in the 1890s, entered the picture.

The upheaval wrought by the Civil War singlehandedly tore a hole in one of the most important bodies of unwritten American culinary knowledge: prewar plantation cookery.

Farmer was an unlikely candidate to transform American cookery. As a teenager in Boston in the 1870s, she suffered a sudden attack of paralysis in her legs, and she was 30 years old before she regained enough mobility to begin taking classes at the nearby Boston Cooking School. Always a lover of food, Farmer proved to be an indomitable student with a knack for sharing knowledge with others. The school hired her as a teacher after she graduated. Within a few years, by the early 1890s, she was its principal.

Farmer started tinkering with a book published by her predecessor a few years earlier, Mrs. Lincoln’s Boston Cook Book. Farmer had come to believe that rigorous precision made cooking more satisfying and food more delicious, and her tinkering soon turned into wholesale revision.

She called for home cooks to obtain standardized teaspoons, tablespoons, and cups, and her recipes called for ultra-precise ingredient amounts, such as ⅞ of a teaspoon of salt and 4 ⅔ cups of flour. Also, crucially, Farmer insisted that all quantities be measured level across the top of the cup or spoon, not rounded in a changeable dome, as American cooks had done for generations.

This attention to detail, advocated by home economists and given life by Farmer’s enthusiasm, made American recipes more precise and reliable than they ever had been, and the wild popularity of Farmer’s book showed how eager home cooks were for such guidance. By the start of the 20th century, instead of offering a few prosy sentences that gestured vaguely toward ingredient amounts, American recipes increasingly began with a list of ingredients in precise numerical quantities: teaspoons, ounces, cups.

In more than a century since, it’s a format that has hardly changed. American cooks today might be reading recipes online and trying out metric scales, but the American recipe format itself remains extraordinarily durable. Designed as a teaching tool for a mobile society, the modern recipe is grounded in principles of clarity, precision, and replicability that emerged clearly from the conditions of early American life. They are principles that continue to guide and empower cooks in America and around the world today.

Helen Zoe Veit is an associate professor of history at Michigan State University, author of Modern Food, Moral Food, and director of the What America Ate Project. This essay is part of What It Means to Be American, a project of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and Arizona State University, produced by Zócalo Public Square.

This article is from the November/December 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Curtis Stone’s Delicious Dishes of the Autumn Harvest

The change of seasons is a tricky time for me, saying goodbye to the fruits and vegetables I’ve fallen in love with using again. Thankfully, there is an overlap between the summer and fall harvest seasons. Some of the best-tasting tomatoes are ripe and ready at the end of September, with earthier squashes and beets soon to follow. By using as many fresh ingredients as possible, you’ll keep meals light and healthy. I milk all I can out of the summer season and love using tomatoes and zucchini in salads, soups, gratins, and pasta.

A quick pasta entrée, Fettuccine with Shrimp and Fresh Tomato Sauce is a guilt-free comfort food with ripened tomatoes, shallots, garlic, and chile peppers that hits all the right notes — tangy and sweet with just a touch of spicy heat. Look for red jalapeños, which are sweeter than the green ones and marry well with the tomatoes.

The weather is still warm enough to fire up the grill and enjoy Grilled Zucchini with Basil and Balsamic Vinegar. The chile and garlic add a nice zip to the dish, while basil and balsamic add a touch of sweetness. A generous portion of the recipe can stand alone as a vegetarian entrée that you can serve with grilled bread and goat cheese.

Editor’s note: Look for the award-winning chef as head judge of Top Chef Junior on Universal Kids.

Fettuccine with Shrimp and Fresh Tomato Sauce

(Makes 4 servings)

- 1 pound dried fettuccine

- 1/4 cup olive oil

- 1 pound large (21-30 count) shrimp, peeled, tails left on, and deveined

- 2/3 cup finely chopped shallots

- 5 large garlic cloves, finely chopped

- 2 red chile peppers, such as Fresno or jalapeños, seeded and finely chopped

- 2/3 cup dry white wine

- 5 large ripe tomatoes (about 2 1/2 pounds), cut into 1/2-inch pieces

- 3 tablespoons coarsely chopped fresh flat-leaf parsley

- 2 tablespoons fresh lemon juice

- 3 tablespoons unsalted butter

Bring large pot of salted water to boil over high heat. Add fettuccine and cook, stirring often to keep strands from sticking together, for about 8 minutes, or until tender but still firm to the bite. Meanwhile, heat large heavy skillet over medium-high heat. Add 2 tablespoons of the oil, then add shrimp and cook, stirring often, for about 2 minutes, or until opaque around edges. Season with salt and pepper to taste. Add shallots, garlic, and peppers, and cook, stirring occasionally, for about 2 minutes or until shallots soften. Add wine and simmer for about 2 minutes, or until reduced slightly.

Drain pasta well, add to shrimp mixture, and toss gently to coat with the sauce. Add tomatoes, parsley, lemon juice, butter, and the remaining 2 tablespoons olive oil and toss again to melt the butter and coat pasta. Season to taste with salt and pepper and toss well. Divide pasta and shrimp among four pasta bowls and serve.

Per serving

- Calories: 782

- Total Fat: 25 g

- Saturated Fat: 8 g

- Sodium: 681 mg

- Carbohydrate: 98 g

- Fiber: 6 g

- Protein: 33 g

- Diabetic Exchanges:

- 5 ½ starch

- 2 lean protein

- 2 vegetable

- 4 fat

Grilled Zucchini with Basil and Balsamic Vinegar

(Makes 4 servings)

- 6 zucchini (about 2 pounds), each cut lengthwise into 3 slices

- 2 1/2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

- 1 red jalapeño chile, seeded and minced

- 2 garlic cloves, finely chopped

- 2 tablespoons balsamic vinegar

- 1/4 cup fresh basil leaves, torn in half

Preheat barbecue for high heat. Coat zucchini with 1 1/2 tablespoons olive oil and sprinkle with salt. Grill zucchini until just charred but still firm, about 3 minutes per side. Transfer grilled zucchini to large baking sheet and set aside until cool. Cut zucchini slices diagonally into 1-inch pieces. Heat large sauté pan over medium heat. Add remaining 1 tablespoon of oil, and then add chile and garlic and sauté until fragrant, about 30 seconds. Add zucchini pieces and toss until warm and then pour in vinegar and toss to coat. Add basil leaves and toss. Season to taste with salt and pepper and serve warm.

Make-Ahead: The zucchini can be grilled 1 hour ahead, cooled, covered, and kept at room temperature.

Per serving

- Calories: 126

- Total Fat: 9 g

- Saturated Fat: 1 g

- Sodium: 91 mg

- Carbohydrate: 9 g

- Fiber: 2 g

- Protein: 3 g

- Diabetic Exchanges:

- 1 1/2 vegetables

- 2 fat

Roasted Salmon and Beets with Herb Vinaigrette

(Makes 4 servings)

- 4 medium beets, preferably golden (1 pound total), scrubbed and very thinly sliced lengthwise

- 6 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

- 1 1/2 pound skinless salmon fillet

- 1 tablespoon finely chopped fresh flat-leaf parsley

- 1 tablespoon finely chopped fresh chives

- 1 tablespoon finely chopped fresh tarragon

- 3 tablespoons finely chopped shallots

- 1 tablespoon grated lemon zest

- 1/4 cup fresh lemon juice

- 4 cups mixed baby greens

Preheat oven to 450°F. On baking sheet, toss beets with 1 1/2 tablespoons of oil to coat. Season with salt and pepper to taste. Arrange beets in center of baking sheet, forming bed large enough to hold salmon. Roast beets for about 20 minutes, or until crisp-tender. Place salmon on top of beets. Brush salmon with 1/2 tablespoon of oil and season with salt and pepper.

In large bowl, mix parsley, chives, and tarragon. Sprinkle all but 1 tablespoon of mixed herbs over salmon. Roast salmon for about 15 minutes, or until cooked to medium-rare doneness so it is slightly rosy in center. Remove from oven.

Meanwhile, whisk remaining 4 tablespoons oil, shallots, lemon zest, and juice into remaining mixed herbs. Season dressing to taste with salt and pepper. Toss mixed greens with 2 tablespoons of dressing. Drizzle remaining dressing over and around salmon and beets and serve greens alongside.

Per serving

- Calories: 460

- Total Fat: 28 grams

- Saturated Fat: 4 grams

- Sodium: 325 mg

- Carbohydrate: 15 grams

- Fiber: 4.5 grams

- Protein: 38 grams

- Diabetic Exchanges:

- 5 lean protein

- 3 vegetables

- 3 fat

“Fettuccine with Shrimp and Fresh Tomato Sauce” and “Grilled Zucchini with Basil and Balsamic Vinegar” are excerpted from What’s For Dinner? by Curtis Stone. Copyright ©2013 by Curtis Stone. “Roasted Salmon and Beets with Herb Vinaigrette” is excerpted from Good Food, Good Life by Curtis Stone. Copyright © 2015 by Curtis Stone. Excerpted by permission of Ballantine Books, a division of Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

This article is an expanded version of the interview that appears in the September/October 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Cartoons: Cooking

Great cartoons spanning 40 years to give you food for thought—and a laugh, of course.

"I want my mother!"

"Now tell me you had this for lunch."

"Mom said for you to wash up for dinner…

and then to cook it."

"That's the last time I try

cooking something from scratch."

"Red or white wine with Presbyterian?"

"My husband ate my homework."