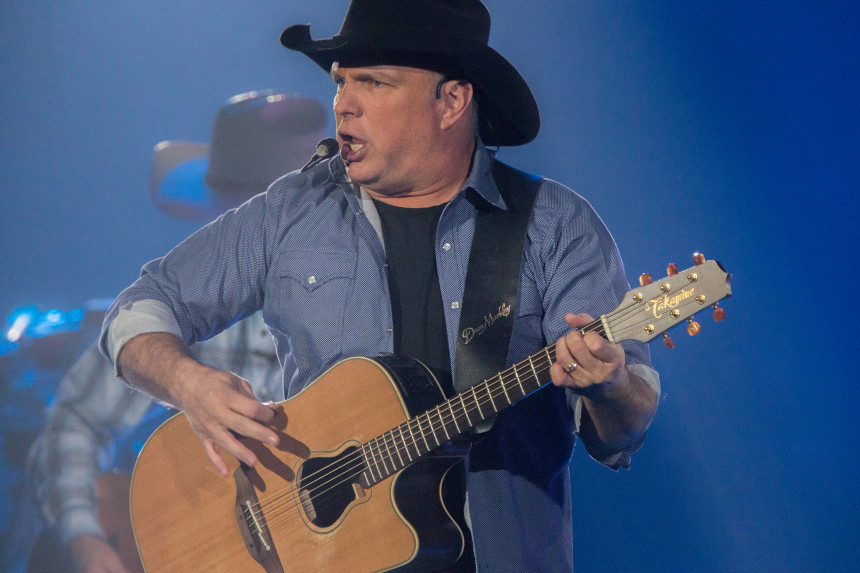

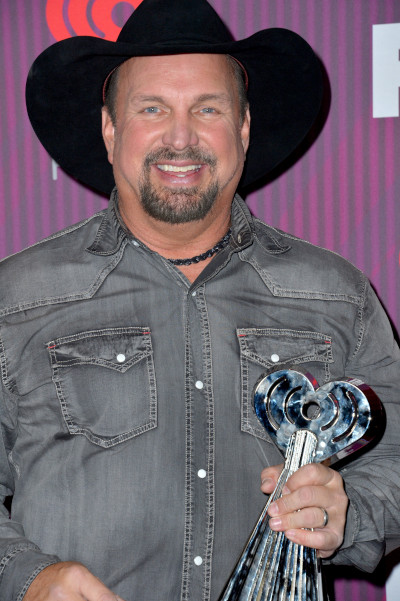

30 Years Ago, No Fences Established Garth Brooks as Country Royalty

It’s hard to decide exactly where to start with Garth Brooks. That he’s the best-selling solo albums artist in the history of the United States? That only The Beatles have sold more albums? What about the fact that he’s the only artist to sell 10 million copies each of nine different albums? Then there’s the pick-up truck full of Grammys, American Music Awards, and gold and platinum records, and that’s before you get to the swelling list of Hall of Fame inductions. He is, after all, the youngest person to receive the Library of Congress Gershwin Prize for Popular Song. And even though his debut album was a hit, Brooks truly ascended to next-level stardom with his second effort, No Fences, which hit stores 30 years ago this week.

If you knew Troyal Garth Brooks in high school, you might be forgiven for thinking of him as an athlete rather than a music guy. Born in 1962 in Oklahoma, Brooks would stand out in track and field, baseball, and football. He even went to Oklahoma State University on a track scholarship, specializing in javelin. But the other side of Brooks was that his mother was Colleen McElroy Carroll, a country singer who had been signed to Capitol Records and performed on television shows like Ozark Jubilee. His family held weekly talent shows that all the kids had to take part in; consequently, Brooks learned to play banjo and guitar. At OSU, his roommate, Ty England, played guitar and would soon become Brooks’s sideman.

Brooks graduated OSU in 1984 with an advertising degree, and the following year he began to play the local circuit. His influences came from a wide spectrum, including rock acts like KISS and singer-songwriters like James Taylor. But George Strait and Chris LeDoux in particular were the artists that drove Brooks toward country. Once he got connected in Nashville via entertainment lawyer Ron Phelps, Brooks was on his way toward his first deal.

Brooks put out his self-titled debut, Garth Brooks, in 1989 on his mom’s old label, Capitol. In his first taste of crossover success, Brooks saw his #2 country album also hit #13 on the Top 200.He wrote or co-wrote the first three singles from the record, all of which went Top 10 country, with “If Tomorrow Never Comes” hitting #1. The fourth single was written by Tony Arata; it was called “The Dance.” The #1 hit made Brooks a star on country television with its emotional video that paid tribute to late public figures from the towering (Martin Luther King, Jr., John F. Kennedy) to the lesser-known (bull rider Lane Frost, singer Chris Whitley). Brooks still considers the worldwide hit to be his favorite song from his own catalog.

However, Brooks’s second effort just a year later would turn out to be landmark not just for him, but for country as a whole. No Fences dominated the Country Albums chart with 23 straight weeks at #1 while also hitting #3 on the Billboard 200. It remains his best-selling individual album, with 17 million copies shipped in the U.S. alone. The album produced four #1 singles (“Friends in Low Places,” “Unanswered Prayers,” “Two of a Kind, Workin’ on a Full House,” “The Thunder Rolls”) and a #7 (“Wild Horses”). In particular, “Friends in Low Places” became a phenom unto itself; after a four-week run at #1, it ended up winning both the Country Music Association and Academy of Country Music Awards for Single of the Year. So pervasive was the song that year that it was a Top 40 hit on the U.K. charts while making the Top 100 on the Eurochart. It now routinely appears on lists of “Best Drinking Songs.”

In stark contrast to “Friends,” “The Thunder Rolls” sparked enormous controversy when Brooks delivered the music video. Composed by Brooks and Pat Alger, the original version of the song had four verses; the song is about a cheating husband, and the last verse suggests that the scorned wife shoots him. Ultimately, the fourth verse was omitted when the song was recorded for the album. However, Brooks felt that he had the opportunity to make a statement, and the moody music video was constructed to make a point about domestic violence. Brooks even portrayed the cheating, abusive husband himself. Almost immediately upon release, TNN (The Nashville Network) and CMT (Country Music Television) banned the video, citing violence and a reluctance to dive into social issues as reasons. VH-1 took up the video a few days later, and Capitol was deluged with requests for the video from alternate venues. The clip was eventually named the CMA Video of the Year and was nominated for a Grammy.

Brooks didn’t let the iron cool before striking again. Ropin’ the Wind shipped four million copies in advance of its September 1991 release. The artist would also soon benefit from the introduction of SoundScan, a new sales tracking system that digitally counted sales by individual unit rather estimates given by store managers and owners. The new system turned album sales on their collective head, demonstrating that genres like country, hip-hop, and alternative rock were actually selling in much larger numbers than had been figured before. The album debuted at #1, was briefly dislodged for two weeks by the release of Use Your Illusion II by Guns N’ Roses, and then retook the top spot for a seven-week run. At the beginning of 1992, Brooks swapped the top spot with Nirvana’s Nevermind before settling in for another eight-week run.

From there, Brooks has had a career that can mostly be summed up by superlatives. His total output since 1989 is substantial on any scale; he’s released 77 singles, 12 studio albums, three Christmas albums, and a number of compilations and boxed sets. While Brooks took his foot off the throttle in the 2000s, actually going 13 years between the releases of Scarecrow and Man Against Machine, and though his most recent studio albums haven’t sold as well, his catalog continues to move and he remains a massive live draw around the world. To date, he’s sold a mind-boggling 170 million records. Brooks has expressed dissatisfaction with the payouts delivered by digital services like iTunes, Spotify, and YouTube, which is why you won’t find his videos on the latter; that situation may have also affected his more recent sales totals in a negative way, given the popularity of digital formats and the fact that those formats now figure into chart data.

Of course, it would be unthinkable to count a personality like Brooks out. Against conventional wisdom, he took a brand of country merged with arena rock to the top of the charts, and kept it there for years. His work remains some of the best known in the genre, and still benefits from significant airplay and back-catalog sales. He’s a member of the Grand Ole Opry, the Country Music Hall of Fame, the Songwriters Hall of Fame, and the Musicians Hall of Fame and Museum. Brooks may have staked out country immortality by singing about friends in low places, but he’s put together a career defined by highs.

Featured image: Sterling Munksgard / Shutterstock

How Urban Cowboy Disrupted Country Music

No matter how you look at the decade, the 1970s were a musical battleground. New and rising genres like disco, punk, funk, and hip-hop arrived as significant acts from the previous decade broke up (The Beatles), faded, or died. The Southern Rock and singer-songwriter movements impacted the charts, as did more socially conscious soul and R&B. In the country music arena, a struggle ensued between a shiny, rhinestone-covered version of the sound and artists who wanted to push for gritand authenticity. By 1980, the clash in country hit a flashpoint in an unlikely place, the John Travolta film Urban Cowboy, which was released 40 years ago this week.

Dolly Parton’s “Here You Come Again” was a #1 pop song in 1977 (Uploaded to YouTube by Dolly Parton)

A fine point about the divergences in country through the 1970s was made in, wouldn’t you know it, The Saturday Evening Post. In a 1975 article, “Nashville – Where It Started,” Paul Hemphill said, “Country music isn’t really country anymore; it is a hybrid of nearly every form of popular music in America.” Hemphill meant the genre wasn’t just cowboy songs or honky tonk or rockabilly; it was a thing that combined all sensibilities, including folk and pop. Song of the biggest stars at the time, like John Denver or Olivia Newton-John, either started in other genres or integrated other styles into the country approach. Denver even won the Country Music Association’s award for Country Music Entertainer of the Year in 1975. Established country artists like Dolly Parton began to regularly score huge hits on the pop charts.

“Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way” by Waylon Jennings (Uploaded to YouTube by Waylon Jennings)

That same year, Waylon Jennings recorded “Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way?” which suggested that a new approach in both style and content was needed in the form. Jennings and other artists like his wife, Jessi Colter, Willie Nelson, Johnny Cash, and others, leaned on a rougher style that became known as Outlaw. Many of those artists chucked the shiny blazers and sparkly suits that had been en vogue for the decade in favor of jeans and leather vests or jackets.

The trailer for Urban Cowboy (Uploaded to YouTube by YouTube Movies / Paramount)

It was against this backdrop that Urban Cowboy came into being. The film drew inspiration from the Esquire article “Urban Cowboy” by Aaron Latham; Latham’s piece centered on a romance at Gilley’s, which was a massive honky tonk club in Pasadena, Texas. Latham and director James Bridges adapted the story into a screenplay with John Travolta and Debra Winger as the leads. It was little wonder that Travolta had an interest in the part; his massive 1977 hit Saturday Night Fever was also based on a magazine piece. Also like Fever, and Travolta’s 1978 hit, Grease, the part would allow him to show his dancing ability against the backdrop of a strong soundtrack (Travolta’s representation had previously suggested he take a cut of the soundtracks for Fever and Grease, a move that paid off to the tune of millions). While the film wasn’t as huge as Fever or Grease, it was a sizeable hit in terms of not just box office, but also fashion and music.

The soundtrack for Urban Cowboy leaned heavily on pop-flavored country and generated five Top 10 country singles (“Love the World Away” by Kenny Rogers; “Look What You’ve Done to Me” by Boz Scaggs; “Stand by Me” by Mickey Gilley; “Lookin’ for Love” by Johnny Lee; “Could I Have This Dance?” by Anne Murray); the latter three all went to #1, and all five crossed over to the Pop Chart. Those songs, along with other hits like Dolly Parton’s title tune from her own 1980 film, 9 to 5, caused a major surge in the popularity of the lighter side of country.

Sylvia performing “Nobody” (Uploaded to YouTube by Sylvia – Topic / Sony Music Entertainment)

However, country traditionalists weren’t exactly thrilled. A definite schism arose in the genre between the rougher outlaw artists and related subgenres, and the more pop-oriented singers and groups. On a commercial level, the pop style was in ascendance, with artists like Rogers and Parton consistently notching hits on both charts. In the wake of the success of Urban Cowboy, new fans of the genre came in concurrent to a spike in the number of stations moving to a country format (some were new, while a few of these had abandoned disco and the 1970s staple AM easy listening formats). TV helped both sides, with the continued success of Hee Haw in syndication showcasing acts from all segments of the country spectrum. Following the lead of 1981’s launch of MTV, the 1983 debut of The Nashville Network gave the genre its own cable platform. Like Hee Haw, the channel featured a variety of artists; however, it did tend to emphasize pop-oriented and video-ready acts like Sylvia, whose “Nobody” went to #15 on the pop charts in 1982.

Of course, no subgenre holds sway forever. Pop crossovers started dropping in the mid-’80s as both the pervasiveness and increased diversity on MTV allowed superstars like Michael Jackson, Madonna, Prince, Bruce Springsteen, and others to dominate the charts, while also allowing booming genres like metal and hip-hop to enjoy crossover success. Country retrenched in the mid-1980s as neotraditionalists like Clint Black, Dwight Yoakam, The Judds, Reba McEntire, and George Strait took over for the rest of the decade.

The Highwomen perform “Redesigning Women.” (Uploaded to YouTube by The Howard Stern Show)

Today, country is as it’s always been: an amalgam of many genres and subgenres. It experienced a huge boom in the early ’90s when SoundScan dramatically changed how sales were counted, and enormous acts like Garth Brooks and Shania Twain were as big as any stars on the planet. Though country still offers the occasional crossover breakout, like Taylor Swift, it’s steady and thriving. Some likened the recent years of male-heavy “bro country” to the Urban Cowboy years, but acts like Brandi Carlile, Maren Morris, the supergroup The Highwomen (of which Carlile and Morris are members), Kacey Musgraves, and Kelsea Ballerini, among others, have carved out a bigger niche for female artists in the last few years. The lesson seems to be that no matter how far you stretch a form, it will at some point always snap back to the essentials. Or, to put it another way, you can put country on the pop charts, but it won’t forget where it came from.

Featured image: ThoseLittleWings / Shutterstock